* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Roman Army

Centuriate Assembly wikipedia , lookup

Culture of ancient Rome wikipedia , lookup

Roman historiography wikipedia , lookup

Late Roman army wikipedia , lookup

Education in ancient Rome wikipedia , lookup

Alpine regiments of the Roman army wikipedia , lookup

Roman agriculture wikipedia , lookup

Roman economy wikipedia , lookup

Military of ancient Rome wikipedia , lookup

Roman funerary practices wikipedia , lookup

Romanization of Hispania wikipedia , lookup

Battle of the Teutoburg Forest wikipedia , lookup

Roman infantry tactics wikipedia , lookup

Roman army of the mid-Republic wikipedia , lookup

Structural history of the Roman military wikipedia , lookup

East Roman army wikipedia , lookup

Imperial Roman army wikipedia , lookup

Roman legion wikipedia , lookup

THE ROMAN ARMY

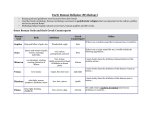

Legion

1 Contubernium - 8 Men

10 Contubernia 1 Century 80 Men

2 Centuries 1 Maniple 160 Men

6 Centuries 1 Cohort 480 Men

10 Cohorts + 120 Horsemen 1 Legion 5240 Men *

*1 Legion = 9 normal cohorts (9 x 480 Men) + 1 "First Cohort" of 5 centuries (but each century a

LEGATUS

The Legatus was typically a senator in his 30s who had been a senatorial tribune and then gone through

the civilian government posts in Rome. He was appointed by the emperor and held command for 3 or 4 years

, although some became very good generals and served much longer. In a province with only one legion

, the legatus also serves as governor; in provinces with multiple legions, each legion has a legatus and th

e provincial governor has command of all of them.

Centurions

Then come the centurions, 59 or 60 to a legion. They have their own very confusing hierarchy

: There are six distinct steps of seniority in each cohort, from lowest to highest: hastatus posterior, hastatus

prior, princeps posterior, princeps prior, pilus posterior, pilus prior. (Note that "pilus" means "file", NOT the

same word as "pilum". In the Republic the triarii were sometimes referred to as "pilani".) The cohorts themselve

s are ranked from the First (highest) to the Tenth (lowest). In theory a centurion would start in the lowest spot in

the Tenth cohort, rise to the top of that, then move to the lowest spot in the Ninth cohort, etc. Probably it never

really happened that slowly. The centurions of the first cohort were called the primi ordines, and were

headed by the primus pilus ("first FILE"!), the senior centurion in the whole legion. From there a man

could rise to praefectus castrorum, third in command of the whole legion, and after a year in that post

he'd retire in fabulous wealth and glory.

Tribunus Laticlivus

Second in command of the legion was the tribunus laticlavus or senatorial tribune, a fresh-faced

young man on his first job away from home. He probably relied heavily on the next man down,

the praefectus castrorum or camp prefect, a grizzled veteran who had been promoted up through

the centurionate. Then came the five tribuni angusticlavi or equestrian tribunes, appointed from

the wealthy class (just below senators). These men actually had more experience than the

higher-ranking senatorial tribune, having just served about three years as independent commanders

of auxiliary cohorts. (Auxiliaries were enlisted from the provinces, and some of them were pretty barbaric

. I wonder if they ever ate their commanders?) It used to be said that the tribunes just held administrative

posts and did not actually lead troops, but now we think that each equestrian tribune commanded tw

•cohorts of legionaries. This would be a logical step up in status from commanding one cohort of auxili

•aries.

• After a term as legionary tribune, an equestrian tribune could be promoted to command of an

• auxiliary cavalry ala ("wing", 24 turmae totalling c. 512 men).

Auxiliary Infantryman

•

Auxiliary Infantryman

•

An auxiliary infantryman of the first century

AD. His armour and equipment is decidedly

inferior to that of the legionary. He wears a

light mail shirt and a Gallic helmet. Instead

of the sophisticated pilum, the throwing

spear of the legionary, he carries the hasta,

a more basic stabbing spear. His light shield

is flat and oval, offering no corners to snag.

It hence is a shield enabling a soldier to fight

individually or in loose formation. This is

equipment suited to a light mobile fighter,

rather than the to the disciplined heavy

infantrymen of the legions.

Republican Legionary

•

A legionary of the late Roman republic. His

armour is light chain mail, and his shield,

though curved, is not yet the famous square

shield of later days.

Vexillarius

1st century AD

•

A first century vexillarius. His armour and

helmet are covered in a bear skin, and he

would usually also carry a small circular

shield.

•

The vexillarius takes his name from the type

of standard he carries, the vexillum. The

vexillum was used as the typical standard for

cavalry or, as in this case, in the infantry for

detachments of varying sizes. Such a

detachment could be of any number of men

and is known as a 'vexillation'.

Their standard would signify which larger

unit they would belong to, in this case the

8th legion.

•

Signifer

1st century AD

•

A first century signifer. His armour and

helmet are covered in a wolf skin, and he

also carries a small circular shield.

•

The signifer takes his name from the type of

standard he carries, the signum. The signum

was used as the typical standard for each

maniple in the legion (a maniple consisted of

two centuries).

Aquilifer

1st century AD

•

A first century aqulifer. His armour and

helmet are covered in a lion skin, and he

also carries a small circular shield.

•

The aquilifer takes his name from the type of

standard he carries, the aquila (the 'eagle').

The aquila was the standard of the legion. It

was the item which had to be defended at all

cost, as it represented the legion's honour.

Bearing the legion's most prized possession

the aquilifer's position was of high standing.

In fact, part of the aquilifer's was to be in

charge of the legion's pay chest. He would

therefore also be the man to whom the

legionaries and officers would entrust their

savings.

•

Cornicen

1st century AD

•

A first century cornicen. His armour and

helmet are covered in a wolf skin, and he

would usually also carry a small circular

shield.

•

The cornicen is one of the trumpeters of the

legion. In battle he would use his horn,

called the cornu, to draw the attention of the

soldiers to any new order being signalled.

Imperial Legionary

1st century AD

in lorica segmentata

•

A legionary wearing the famous banded

armour, the lorica segmentata, and the

typical imperial 'Gallic' helmet. Also he has

with him the famous large square shield.

Imperial Legionary

1st century AD

in lorica hamata (chain

•

A first century legionary wearing chain mail

armour, the lorica hamata, and the typical

imperial 'Gallic' helmet. Also he has with him

the famous large square shield.

Centurion

•

•

•

•

The centurion's armour varied widely, perhaps it

was even a matter of individual choice. The

centurion depicted wears leather. The rings (torques)

and circular plaques (phalerae) on his torso are

awards he has won in battle, comparable to medals

in modern day armies.

The horsehair crest across his helmet made him

easily recognizable by everyone, even in the chaos

of batte, as a officer of considerable rank.

The greaves he wears to protect his shins are also a

sign of his being a centurion. A cape was usually

also seen as a mark of a centurion. Although, given

that their style of dress may well have been down to

their own choice, this centurion may not be at all out

of place without such a cape.

Note also the vine rod he holds in his hand. A further

insignia of his rank and one he would happily use to

beat unruly soldiers with to enforce discipline.

Legatus

1st century AD

•

•

The legatus was the commaner of a legion.

He would be of senatorial rank.

He wears a bronze chest plate and the

purple on his tunic points to his being of the

senatorial order.

Imperator

•

•

The term imperator strictly speaking only

befitted a victorious Roman commander.

Republican commanders such as Julius

Caesar were hailed imperator by their troops

after victories. However, it was a title which

the emperors chose for themselves as

commander in chief of the Roman imperial

army.

In this case, you see a suggested recreation

of emperor Hadrian's appearance.

Legionary in Practice

•

The soldiers of the Roman army would daily

practice their combat skills. For this they

would use shields made from wickerwork

and wooden swords in order not to injure

each othe

'Marius Mule'

•

•

The soldiers of the Roman army would

carry with them a considerable abmount of

kit. When on the march they carried over

their shoulder a contraption (sometimes

described as a forked stick) which would

help them to carry some of their equipment.

Here is an of an legionary bearing this item

over his shoulder together with his pilum.

So weighed down were the soldiers by all

their stuff, that they were nicknamed 'Marius'

mules' (after the famous Roman general to

whom the invention of the very forked stick

is ascribed).

Late Cavalryman

•

•

•

•

An example of a late Roman cavalryman, perhaps

5th century AD. His helmet and chainmail already

look very much like the armour of later medieval

knights. He bears a light, round shield and a lance

for stabbing. The sword of the Roman cavalryman

was the spatha, a long-bladed weapon, granting the

rider a much greater reach than the legionary's short

gladius.

Much of the precise armoury and weaponry of late

Roman cavalry is guesswork. In this case, spot the

quiver carried behind the saddle, holding arrows for

use with the bow.

The prefered mode of battle for the Roman cavalry

(ala) was fall into the rear or the flanks of an enemy

already deployed against Roman infantry. It proved

at its most devastating when it rode down fleeing

troops, lancing the fleeing soldiers in their backs. In

fact most of the slaughter in ancient battles is

thought to have occured, when the opposing army

broke and fell into disorder and the cavalry fell upon

the panicked and fleeing enemy.

Note that the Roman cavalry rode without stirrups.

The Tortoise

The 'testudo'

The tortoise formation was one of the prime examples of Roman ingenuity at warfare. When deployed

in such a way, the legionaries became virtually invulnerable to arrows or objects dropped from

defensive walls.

The Wedge

•

The wedge was an aggressive formation used to 'crack open' enemy lines. Relatively small groups

of legionaries could form such a triangle and then drive their way into the enemy ranks. As more

Roman soldiers reinforced the wedge from behind, the enemy line could be forced apart. As

breaking the enemy's formation was very often the key to winning a battle, the wedge formation

was vitally important battlefield tactic of the Roman army.

The Skirmishing Formation

•

•

•

•

•

The skirmishing formation is essentially the opposite to the closely packed line of battle used by legionaries. It is a

widely spaced line. Every second man of the line has stepped forward a few paces, effectively doubling the amount

of ranks. However, the gaps created by this formation are always overlapped by the next line to follow.

The roots of this formation are more than likely to be found with the velites, the lightly armed skirmishers who

operated ahead of the main force in the early Roman army.

The wide spaces allow each soldier great mobility. Its possible uses were manyfold.

It would make an advance over difficult terrain much easier. It could allow for swift attacks with subsequent quick

withdrawals. It would allow for any friendly units falling back to pass through the formation.

It also could be used by a victorious army sweeping over the battle field, killing all that was left in its way.

Repel Cavalry !

•

•

The order to repel cavalry by Roman army officers brought about a defensive formation, in which the front rank

formed a tight wall of shields with their pila protruding to form a line of spearheads ahead of the wall. Undoubtedly it

would be very hard to bring a horse to break into that formation. The most likely occurrence would be that it would

come to a halt of its own will ahead of the spearheads. It was at that moment that horse and rider would be at their

most vulnerable against the ranks behind the first line of infantry which would then hurl their spears at them. Given

the short distance and the training legionaries received, it is likely such halted cavalry, frantically trying to turn their

horses around to retreat, whilst colliding with horses following in the charge, would prove very easy targets.

If one further considers the likely possibility of archers being present, as is the case on the photo above, the effect of

this formation could indeed be devastating.

The Orb

•

•

•

•

The orb was a defensive formation in the shape of a complete circle which could be taken by a unit which had either

become detached from the army's main body and had become encircled by the enemy, or a formation which might be

taken by any number of units if the greater army had fallen into disorder during a battle.

It can hence be seen as a formation representing a desperate 'last stand' by units of a collapsing army. But also it can

be seen as a disciplined holding position by a unit which has been divided from the army's main body in battle and

which is waiting for the main force to rejoin them.

In either case, it is not a formation one would like to find oneself in, as it obviously indicates that they are surrounded

by the enemy.

Naturally any officers or archers would be positioned in the centre of the orb, as can be seen in the example above.

The Siege Tower

•

•

A model of a Roman siege tower at the

Museo della Civilta in Rome. This collossal

tower on wheels would mainly be used to

provide height for archers and ballista

catapults. From this vantage point they

would be able to fire their arrows and bolts

at the men atop a city's walls and turrets,

thus allowing the Roman soldiers to work on

creating a hole in the wall, without being

attacked from above.

This particular model even has the ram built

into its base, so that the soldiers operating it

can work within the safety of the tower.

The Ballista

The Scorpio-Ballista

•

A photo of a recreated Roman ballista-type

'Scorpion' catapult. In essence it's much the

same, but smaller than a basic 'ballista'.

The Onager

•

A model of an onager catapult at the Museo

della Civilta in Rome. This machine would

be the heavy artillery to the ancient world.

The handles to the left (rear of the catapult)

are in fact levers by which the soldiers would

wind the throwing arm back. On the right

you see a cushion at the front of the

catapult. No doubt it was there to soften the

blow of the throwing arm and so help to

prevent the machine from tearing itself

apart.