* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Smallpox Eradication Story The story of the eradication of smallpox

Influenza A virus wikipedia , lookup

2015–16 Zika virus epidemic wikipedia , lookup

Leptospirosis wikipedia , lookup

Oesophagostomum wikipedia , lookup

Onchocerciasis wikipedia , lookup

Orthohantavirus wikipedia , lookup

Neonatal infection wikipedia , lookup

Hospital-acquired infection wikipedia , lookup

African trypanosomiasis wikipedia , lookup

Ebola virus disease wikipedia , lookup

Hepatitis C wikipedia , lookup

Schistosomiasis wikipedia , lookup

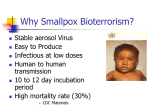

Bioterrorism wikipedia , lookup

Human cytomegalovirus wikipedia , lookup

Herpes simplex virus wikipedia , lookup

Siege of Fort Pitt wikipedia , lookup

Middle East respiratory syndrome wikipedia , lookup

West Nile fever wikipedia , lookup

Marburg virus disease wikipedia , lookup

Henipavirus wikipedia , lookup

Hepatitis B wikipedia , lookup

Eradication of infectious diseases wikipedia , lookup

Smallpox Eradication Story The story of the eradication of smallpox demonstrates the power of vaccination over a virus that existed for thousands of years. Smallpox Infection Smallpox , a disease caused by Variola virus, is transmitted through respiratory secretions and contact with the virus. After an incubation period , the time between exposure to the virus and the appearance of symptoms, of seven to seventeen days, the infected person develops fever, headache, malaise, and aches. This is known as the prodromal stage of the illness and lasts approximately two days. After this, a rash develops in the mouth and throat and then spreads to the face, arms, and legs. The rash then moves to the hands and feet and the torso. Finally, the rash changes to fluid - filled vesicles, which contain virus, that scab over after about two weeks. The infected person is contagious until all of the scabs have fallen off. The development of the vesicles and scabs usually results in scarring on the person ’ s skin, which visibly distinguishes them as a smallpox survivor. Smallpox Pustules on a Child Source: CDC Public Health Image Library. History of Smallpox Reliable written accounts of smallpox infection exist from at least the fourth century AD, but there is evidence that the disease was present well before that time. Several Egyptian mummies dating back to 1200 – 1100 BC have been noted to have lesions consistent with smallpox infection, and the disease is believed to have been the cause of their deaths [4] . By the fifth century AD, smallpox epidemics occurred in Asia, India, and Europe. In Africa, smallpox devastated communities that had never been affected by the disease before it was brought in by ships supplying European settlements in the fifteenth century. In turn, settlers from Europe and slave ships from Africa brought the disease to colonial America. Although some colonists had already been infected with smallpox and developed immunity to the disease, the Native American population of North America was not immune and was devastated by smallpox. Colonists sometimes took advantage of the susceptibility of the Native American population and helped to spread the disease among them. There is speculation that in the eighteenth century smallpox was used as a bioweapon against the Native American population by giving them blankets inoculated with the virus [5] . It would be impossible to account for the full number of deaths caused by smallpox worldwide throughout history, but regional epidemics provide a picture of the ability of the disease to devastate populations. In London there were 36,000 deaths attributable to smallpox from 1780 to 1800 [6] . In Quebec City, Canada, an outbreak at the start of the eighteenth century is believed to have killed 25 percent of the population. By the late eighteenth century, smallpox is believed to have killed approximately 400,000 people in Europe yearly. Notable deaths due to smallpox include Ramses V of Egypt in 1157 BC, Queen Mary II of England in 1694, and King Louis XV of France in 1774. Control of Smallpox Infection One of the early methods used to protect against naturally acquired smallpox infections was the practice of variolation (also referred to as inoculation ). This practice can be traced to China in 1000 AD and likely also took place in India around the same time. Variolation involved inoculating variola virus from the smallpox scabs of one person into the skin of a nonimmune person. This usually resulted in a less severe smallpox infection with less scarring and a lower mortality rate than naturally acquired smallpox, but still left the person with immunity against the smallpox virus. The reasons for the difference in severity are not known. The practice of variolation spread from India to Asia to Central Europe. In Turkey, Lady Mary Wortey Montague, a British aristocrat living in Constantinople with her ambassador husband and two children, adopted the practice of variolation [4] . In 1715, Lady Montague became infected with smallpox; her brother had died from the disease at the age of twenty. Determined to protect her children from smallpox, Lady Montague had her five - year - old son inoculated against smallpox in Turkey. The family returned to London in 1721, where she had her daughter inoculated in the presence of notable physicians. This action is credited with promoting the wide adoption of variolation in England in the eighteenth century, and the practice then spread to the British colonies in North America. Despite the success of variolation, the practice did have some drawbacks. The mortality rate for variolation was about 0.5 percent to 2 percent, which is lower than the 30 percent mortality rate for naturally acquired smallpox but still high enough to discourage some people from the practice. In addition, variolation of the skin carried a risk of bacterial infection from the incision that was made to introduce the virus into the system, and often people who underwent variolation had a mild illness that allowed them to remain mobile and then spread the disease to others who were not immune. In the late eighteenth century, thanks to the observations of British physician Edward Jenner who himself underwent variolation in 1756 as a boy, the process of variolation began to be replaced with a safer method of protecting people against smallpox called vaccination . It was known in the British countryside at this time that milkmaids were prone to an infection acquired from cows, called cowpox, which resulted in lesions on the hands that resembled smallpox. In contrast to smallpox, cowpox infection was minor, it did not spread from human to human, and it seemed to protect the milkmaids against smallpox infection. Edward Jenner hypothesized that variolation with cowpox virus would protect against infection with smallpox. His opportunity to test this hypothesis came in 1796, when a milkmaid named Sarah Nelmes developed cowpox virus. Jenner isolated the material in the pustules on her hand and used it to inoculate eight - year old James Phipps, who had never had smallpox disease or undergone variolation. When Phipps was later variolated with smallpox virus, he did not develop the disease, supporting Jenner’s hypothesis that cowpox infection could protect against smallpox infection. Jenner published his fi ndings and named his protective method Variolae vaccinae , deriving vaccinae from the Latin term for “ cow, ” vaca . The term vaccination, now widely used, arose from this practice. Eradication of Smallpox Jenner ’ s vaccination gained popularity and was used worldwide to protect against smallpox infection. Originally, the virus was passed from person to person through vaccine chains consisting of unvaccinated people, sometimes orphans, who were successively vaccinated to maintain the supply of virus. This arm - to -arm vaccination method was used to transport vaccine throughout the world. In the early twentieth century, vaccine production occurred in factories, and the vaccine strain itself changed from cowpox virus to Vaccinia virus, a virus of unknown origin that became the modern smallpox vaccine. Smallpox was eradicated in North America by 1952 and in Europe by 1953. But in India and in many African countries smallpox was still endemic. In 1959 it was proposed that the World Health Organization (WHO) should undertake the smallpox eradication program with the goal of making it the first infectious disease to be eradicated by humans. Smallpox was an excellent candidate for eradication because the vaccine was highly effective in preventing disease and could survive without refrigeration, and vaccination left a scar as proof that a person was immune. In addition, the smallpox virus does not mutate frequently, so repeated vaccination was not necessary. Eradication efforts were hampered initially by lack of funding and low interest in smallpox as a target disease for eradication. Eradication efforts were stepped up in 1967, and the success of the program was supported by an increase in vaccine production and better methods of vaccination. Less than two hundred years after the discovery of Jenner ’s smallpox vaccine, the last naturally occurring smallpox infection was identifi ed in a village in Somalia in a man named Ali Maow Maalin in 1977. The final chapter in the eradication of smallpox was to be the destruction of all smallpox laboratory strains, initially set to occur in 1993 and then delayed until 1995, and then delayed again until 1999. After that time, perceived threat of the use of smallpox as a bioterrorist weapon again caused a delay in destruction of virus stocks. As of 2010, smallpox is still being studied in laboratories and debate continues on whether and when the virus stocks should be destroyed. Source: Prins C. Chapter 8: Infectious Disease Epidemiology. In Public Health Foundations-Concepts and practices. Editors: Andresen E, Bouldin ED. A Wiley Imprint. 2010. Osmanlılarda çiçek aşısı: http://www.ttb.org.tr/eweb/asi_brosur/tarih.htm Bu topraklarda deneme yanılma yoluyla aşı uygulamalarının tarihi 1700'lere uzanmaktadır. O zamanlar Edirne'de çiçek hastalığına tutulmuş biri bulunup, döküntülerindeki irin, çiçek çıkarmamış çocuklara aşı yapmak üzere toplanırmış. Geleneksel olarak bu işi yapan aşıcı kadınlar, ceviz kabuklarında ya da incir yapraklarında hastaların döküntülerinden alınan irini biriktirir, deriyi çizerek bu irini aşılar, sonra yara yerini gül yapraklarıyla kapatırlarmış. Bu şekilde, variyolasyon ile aşılananların ölüm oranı % 1 iken, aşısızlarda, çiçek hastalığından ölüm oranı % 17 imiş. Bu uygulamalar İngiliz sefirinin eşi Lady Montagu tarafından mektupla İngiltere'ye bildirilmiş ve bu yolla Avrupa'ya yayılmıştır. Ülkemizde 1800'lerde daha etkili ve daha az zararlı olan Jenner tipi vaksinasyon uygulamaları başlamıştır. 1840'tan itibaren başvuran çocuklara çiçek aşısı uygulanmıştır. Yine bu dönemde çiçek aşısı yapmak üzere aşıcıların yetiştirilmesi gündeme gelmiştir. 1868 yılında çıkan bir kanunla doğumdan itibaren ilk üç ay içinde çiçek aşısı uygulanması zorunlu hale getirilmiştir.