* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

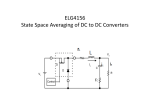

Download Section 3: Switching Regulators

Mercury-arc valve wikipedia , lookup

Spark-gap transmitter wikipedia , lookup

Stepper motor wikipedia , lookup

Power engineering wikipedia , lookup

Three-phase electric power wikipedia , lookup

History of electric power transmission wikipedia , lookup

Electrical ballast wikipedia , lookup

Stray voltage wikipedia , lookup

Power inverter wikipedia , lookup

Surge protector wikipedia , lookup

Integrating ADC wikipedia , lookup

Electrical substation wikipedia , lookup

Voltage optimisation wikipedia , lookup

Power MOSFET wikipedia , lookup

Current source wikipedia , lookup

Schmitt trigger wikipedia , lookup

Resistive opto-isolator wikipedia , lookup

Variable-frequency drive wikipedia , lookup

Mains electricity wikipedia , lookup

Pulse-width modulation wikipedia , lookup

Distribution management system wikipedia , lookup

Alternating current wikipedia , lookup

Voltage regulator wikipedia , lookup

Current mirror wikipedia , lookup

Opto-isolator wikipedia , lookup