* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Common Types of Valvular Heart Disease

Survey

Document related concepts

Electrocardiography wikipedia , lookup

Management of acute coronary syndrome wikipedia , lookup

Cardiac contractility modulation wikipedia , lookup

Heart failure wikipedia , lookup

Coronary artery disease wikipedia , lookup

Myocardial infarction wikipedia , lookup

Rheumatic fever wikipedia , lookup

Artificial heart valve wikipedia , lookup

Cardiac surgery wikipedia , lookup

Jatene procedure wikipedia , lookup

Dextro-Transposition of the great arteries wikipedia , lookup

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia wikipedia , lookup

Quantium Medical Cardiac Output wikipedia , lookup

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy wikipedia , lookup

Lutembacher's syndrome wikipedia , lookup

Transcript

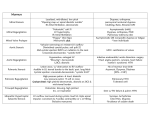

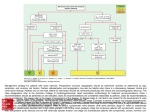

Common Types of Valvular Heart Disease Patients with valvular heart disease comprise a significant portion of many a clinician’s daily practice. Join Dr. Trebichavsky and Dr. Kornbluth as they outline the pathophysiology, symptoms, clinical findings and management associated with common types of this disease. Josée Trebichavsky, LL.B, BCL, MD; and Murray Kornbluth, MD, FRCPC Presented at McGill University’s 58th Annual Refresher Course for Family Physicians, Montreal, Quebec, November 2007. Aortic stenosis (AS) AS is usually an idiopathic disease which results from degeneration and calcification of the aortic cusps. In patients < 65-years-of-age, the most common etiology is that of a congenitally bicuspid valve. Pathophysiology Briefly, the pathophysiology of AS involves compensatory hypertrophy of the left ventricle as the severity of AS worsens. The left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) serves to maintain a constant and normal cardiac output. However, the compensatory hypertrophic process is eventually overcome by the high left ventricular (LV) intracavitary pressures. This leads to LV systolic dysfunction (LVSD) and heart failure (HF). Mr. Stewart’s Case Mr. Stewart is a 65-year-old male who presents with a systolic ejection murmur. His ECHO reveals severe aortic stenosis with an aortic valve area of 0.7 cm2 and a left ventricular ejection fraction of 60%-65%. What symptoms might he be experiencing? For the correct answer, turn to page 28. n o i t u t ibad, h r t g i s i r Dn downlo y l p a i o c C mmeisred usersecrasonal use or rp Cbo Auth copy fo r . d o e e se prohi itint a single l Definition of severity a S Mrs. Huynh’s Case u d pr oaruthobyrithesedaortic anarea, The severityo of t ASf is defined valve as well w e i N Unbetween lay, v as by the mean gradient dispthe left ventricle and the aorta during systole. Generally speaking, an aortic valve area < 1.0 cm2 with a mean gradient of at least 40 mmHg is defined as severe stenosis. Moderate stenosis encompasses an aortic valve area between 1.0 cm2 and 1.5 cm2 with mean gradients usually ranging between 25 mmHg and 40 mmHg. Mildly stenotic valves are those with a valve area between 1.6 cm2 and 2.0 cm2 with gradients < 25 mmHg. Symptoms The classic symptoms of AS are angina, syncope and dyspnea. These symptoms carry significant prognostic importance. Namely, once angina, syncope or HF develops, life expectancy is greatly reduced. Specifically, if the aortic valve is not replaced, mortality associated with the development of angina is approximately 50% within five years. There is a 50% mortality rate within three years after the development of syncope, Mr. Godin’s Case © Mr. Godin is a 55-year-old male who presents with significant dyspnea. On exam, you hear a blowing decrescendo diastolic murmur at the left sternal border. What it your diagnosis and how do you proceed? To find out more, turn to page 28. Mrs. Huynh is a 35-year-old female who, on her annual physical examination, is found to have a low-pitched diastolic rumble at the apex. On further questioning, she admits to palpitations and low threshold dyspnea (New York Heart Association [NYHA] Class 3-4). Her ECHO reveals severe mitral stenosis with a mitral valve area of 0.7 cm2. What management options are available? To find out more, turn to page 28. Mr. Hadjis’ Case Mr. Hadjis is a 45-year-old male who is asymptomatic. On auscultation, you hear a holosystolic murmur at the left ventricular apex. You also note a third heart sound. What other findings would you expect on the physical exam? For the correct answer, turn to page 28. whereas the onset of dyspnea carries a 50% mortality rate within two years of its onset. Perspectives in Cardiology / October 2008 25 Valvular Heart Disease Physical findings Mitral stenosis (MS) The hallmark sign of AS is a systolic ejection murmur that radiates into the carotids. The murmur is usually best heard in the second right intercostal space. Sometimes, it may be heard best in the apical area and may be confused with mitral regurgitation (MR) (Gallivardin’s phenomenon). As the severity of stenosis increases, the murmur peaks progressively later in systole (Table 1). The intensity of the murmur is not a reliable indicator of the severity of the stenosis since the murmur may become soft and sometimes even inaudible as the cardiac output diminishes with progressive LVSD. The carotid upstroke classically becomes diminished in amplitude and delayed in time, so-called “parvus et tardus.” Another sign of severe AS includes a soft or absent aortic component of the second heart sound. The second heart sound also may become paradoxically split due to a delay in LV ejection time. The apical impulse is sustained throughout most, if not all of systole due to LVH. MS is usually a sequela of rheumatic heart disease and primarily affects women. Less common causes include: • congenitally malformed valves, • idiopathic calcification and • systemic lupus erythematosus. Management The perfectly asymptomatic patient with severe AS and normal LV systolic function may be followed every six months for the development of symptoms or LVSD as assessed by echocardiography. In some sedentary patients who are “asymptomatic,” exercise stress testing may be useful to establish the symptomatic state more objectively. The test can be performed safely in these patients if great caution is used in the presence of a physician. Here, exercise testing may provide additional information on which to base clinical decision-making. The decision to replace the aortic valve in a patient with severe AS is dependent on two critical factors: 1. The presence of symptoms 2. Development of LVSD in the asymptomatic patient Since there is no proven medical therapy, aortic valve replacement with either a biological or a mechanical prosthetic valve is generally recommended for the following patients: 1. The asymptomatic patient with LVSD 2. The symptomatic patient 3. The patient with moderate or severe stenosis undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting surgery or other valve surgery 26 Perspectives in Cardiology / October 2008 Pathophysiology The symptoms of MS are related to the increased left atrial pressure and the reduced cardiac output primarily caused by impaired filling of the left ventricle. As left atrial pressure progressively rises with increasing obstruction of LV filling, pulmonary hypertension (HTN) develops, eventually compromising right ventricular systolic function. At this point, symptoms of right-sided HF may appear. Definition of severity Severity of MS is determined by the mitral valve area and the mean gradient between the left atrium and the left ventricle during diastole as assessed by echocardiography. In general, severe MS is defined as a mitral valve area below 1.0 cm2 with a mean gradient above 10 mmHg. Moderate stenosis is defined as a mitral valve area between 1.0 cm2 and 1.5 cm2 with mean gradients between 5 mmHg and 10 mmHg and mild stenosis shows a mitral valve area between 1.6 cm2 and 2.0 cm2 with mean gradients across the valve below 5 mmHg. Symptoms Patients with MS complain of dyspnea on exertion, orthopnea and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea. Less frequent symptoms include hemoptysis, hoarseness and symptoms of right-sided HF. Often the patient remains asymptomatic until the development of atrial fibrillation (AF) when dyspnea or orthopnea are noted as a consequence of a shortened diastolic filling time. Physical findings The classic sign on physical examination of severe MS is the diastolic rumble that follows an opening snap. The diastolic rumble is low pitched and thus best heard with the bell of the stethoscope placed on the apex when the patient is lying in the left lateral decubitus position. The duration of the murmur correlates with severity. At the end of diastole, the atrial kick intensifies the rumble (pre-systolic accentuation). If the Valvular Heart Disease mitral valve is pliable and non-calcified, the first heart sound is characteristically loud due to the force of ventricular systole closing the valve. Valvular severity can be estimated by assessing the time interval between the aortic component of the second heart sound and the opening snap. As MS becomes progressively more severe, the so-called A2-OS interval shortens. Other findings of severe MS complicated by pulmonary HTN include the presence of: • a loud pulmonic component of the second heart sound, • a right ventricular heave, • elevated neck veins and • peripheral edema. Management Medical therapy for symptoms associated with severe MS includes diuretics, which effectively lower left atrial pressure, thereby reducing symptoms. If AF develops, rate control with digoxin, a ß-blocker or a calcium channel blocker is crucial for ensuring adequate LV filling time. Anticoagulant therapy is mandated since there is a high risk of embolism in patients with chronic AF and MS. Balloon valvuloplasty provides excellent mechanical relief of severe MS that usually results in prolonged benefit. Strict contraindications to balloon valvuloplasty include the presence of a left atrial or appendage clot or the presence of significant MR. As well, valvuloplasty is most effective in the absence of significant valvular or subvalvular calcification and thickening. In cases where valvuloplasty is not feasible or appropriate, mitral valve replacement (MVR) is highly effective in improving survival and reducing symptoms. MVR is generally reserved for patients with severe MS who experience severe symptoms (New York Heart Association [NYHA] Class 3 or 4) or those who show evidence of significant pulmonary HTN. Dr. Trebichavsky is a First-year Resident in Internal Medicine, based at the Montreal General Hospital site, MUHC, Montreal, Quebec. Dr. Kornbluth is the Director of Cardiology and Cardiac Intensive Care Unit, Montreal General Hospital site, MUHC, Montreal, Quebec. Chronic aortic regurgitation (AR) Chronic AR results from disease of either the aortic cusps or the aortic root that distorts the leaflets thereby preventing their coaptation. Common leaflet abnormalities include bicuspid valves, as well as infective endocarditis and rheumatic fever. Aortic root causes of AR include idiopathic root dilatation and collagen vascular disease. Pathophysiology Chronic AR is a volume overload state akin to chronic MR. LV enlargement due to excess volume produces a large total stroke volume that, unlike MR, is entirely ejected forward. Increased stroke volume causes an increase in pulse pressure, which leads to systolic HTN. Common symptoms of chronic severe AR include: • dyspnea, • orthopnea, • paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea and • angina. Physical findings A large total stroke volume in chronic AR increases pulse pressure which leads to a myriad of clinical signs, such as de Musset’s sign (rhythmic head bobbing) and Mueller’s sign (systolic pulsation of the uvula). The typical diastolic murmur is decrescendo and blowing, which is heard along the left sternal border if the etiology of the regurgitation relates to a leaflet problem. The murmur is best heard at the right sternal border when the etiology is that of a dilated aortic root. Duration of the murmur correlates with the severity of the regurgitation. The apical impulse is diffuse, displaced and sustained. A third and fourth heart sound may be detected. Management Medical therapy may offer symptomatic relief, but does not alter the natural history of the disease. Again, diuretics and vasodilators may help with symptoms. In general, the “55 rule” is useful in gauging the timing of surgery. Namely, the asymptomatic patient with normal LV size and systolic function may be monitored every six months. Aortic valve replacement is indicated for the asymptomatic patient with a LV ejection fraction < 55% or LV enlargement as defined by a LV endsystolic dimension measuring > 55 mm. Finally, replacement Perspectives in Cardiology / October 2008 27 Valvular Heart Disease Mr. Stewart’s case cont’d... Mr. Stewart has severe aortic stenosis. The classic triad of symptoms includes: • dyspnea, • syncope and • angina. Each symptom carries prognostic relevance and mandates surgical intervention even in the presence of normal LV systolic function. Mr. Godin’s case cont’d... Mr. Godin has findings consistent with chronic aortic regurgitation. Documentation of the valvular pathology and LV function and size is required with echocardiography. Because he is symptomatic, surgical intervention is indicated. Mrs. Huynh’s case cont’d... Mrs. Huynh has severe mitral stenosis. Given the presence of symptoms, relief of the obstruction to left ventricular filling is required. Ideally, this is accomplished by balloon valvuloplasty, assuming that there are no contraindications and that the valve is structurally amenable to this therapy. If valvuloplasty is precluded, MVR is warranted. Medical therapy, in anticipation of invasive intervention, consists of maintenance of sinus rhythm and the use of diuretics. Mr. Hadjis’ case cont’d... Mr. Hadjis has findings consistent with chonic severe mitral regurgitation. Other possible findings on physical exam include a displaced apical impulse, a diastolic rumble mimicking MS and signs of left ventricular heart failure. of the valve is indicated for all patients with significant symptoms. Chronic MR The most common causes of chronic MR include: • mitral valve prolapse (MVP), • chronic ischemia and • degenerative disease. 28 Perspectives in Cardiology / October 2008 Pathophysiology Chronic MR leads to volume overload of the left ventricle. The left ventricle increases in size in order to maintain a normal cardiac output in the context of regurgitation of blood back into the left atrium. Progressive enlargement of the left atrium with increased left atrial compliance protects against high left atrial pressures. Progressive eccentric hypertrophy of the left ventricle ensures a normal filling pressure. LV ejection fraction is super normal due to optimal loading conditions. Symptoms Patients with chronic MR may eventually develop symptoms typical of left-sided HF which include: • dyspnea on exertion, • orthopnea and • paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea together with fatigue. Physical findings A high-pitched holosystolic apical murmur heard best at the LV apex and radiating to the axilla is the classic physical finding. MVP is associated with systolic clicks preceding the murmur. Patients with MVP or papillary muscle dysfunction may exhibit a mid-to-late systolic murmur. A displaced apex points to the development of cardiac enlargement. Rapid filling of the left ventricle by the large volume of blood stored in the left atrium causes a third heart sound. A low-pitched diastolic rumble may be heard at the apex and denotes the large volume filling the left ventricle in early diastole. This mimics the diastolic rumble of MS (pseudo MS). However, unlike true MS, a loud first heart sound and an opening snap are absent. Management As in chronic AR, medical therapy has not been shown to alter the natural history of the disease; however, diuretics and vasodilators may afford symptomatic relief. Definitive treatment is surgical. As such, mitral valve repair is always preferable to MVR whenever feasible. A major advantage of repair is post-surgical preservation of LV systolic function. Mitral valve repair also obviates the need for anticoagulant Valvular Heart Disease Table 1 Ausculatory findings associated with common valve problems1 Lesion Cardiac cycle Quality Location Other sounds Aortic stenosis • Systolic • Mid-peaking to late-peaking Harsh Aortic area, left sternal border, apex • Soft S2 • S4 Mitral stenosis • Diastolic • Increases with atrial contraction if in sinus rhythm Rumble Apex • Opening snap • Loud S1 Aortic regurgitation • Diastolic • Early decrescendo Blowing Left sternal border, aortic area • S3 and/or S4 Mitral regurgitation • Holosystolic • Late systolic with MVP, papillary muscle dysfunction Blowing Apex, axilla • Click(s) with MVP • Soft S1 • S3 MVP: Mitral valve prolapse therapy in patients with a normal sinus rhythm. The timing of surgical intervention and the decision to proceed with surgery depends on the patient’s symptomatology and LV systolic function and size. The asymptomatic patient with an ejection fraction of ≥ 60% and a LV end-systolic diameter < 40 mm may be followed every six months. A decreasing ejection fraction, progressive LV dilatation or the onset of symptoms mandates surgery. In the event that the mitral valve cannot be repaired, replacement of the mitral valve with either a biological or mechanical prosthesis is required. predicated on the presence of significant symptoms and the health of the left ventricle in general and not the degree of severity of the valvulopathy in and of itself. Patients with valvular heart disease comprise a significant portion of many a clinician’s daily practice and familiarity with presenting symptoms, clinical findings and management is crucial. PCard Final thoughts Valvular heart disease is an exciting and intellectually challenging field for the clinician in the broad scope of cardiac pathologies. A good understanding of the pathophysiology of the various valvular lesions helps the clinician in the overall assessment of the patient. A careful history and physical exam are essential and irreplaceable in diagnosing and managing patients with various valvular pathologies. Management of patients with valvular heart disease is Reference 1. Curtin R, Griffin B: Valvular Heart Disease. ACP Medicine. Cardiovascular Medicine: XI, June 2006. Resources 1. Bonow R, Carabello BA, Chatterjee K, et al: ACC/AHA 2006 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006; 48(3):e1-148. 2. Lilly L (ed.), Pathophysiology of Heart Disease. Third Edition. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia, 2003. Perspectives in Cardiology / October 2008 29