* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download View/Open - Cadair - Aberystwyth University

Symbolic interactionism wikipedia , lookup

Public engagement wikipedia , lookup

Community development wikipedia , lookup

Social psychology wikipedia , lookup

Intercultural competence wikipedia , lookup

Social Bonding and Nurture Kinship wikipedia , lookup

History of social work wikipedia , lookup

Anti-intellectualism wikipedia , lookup

Unilineal evolution wikipedia , lookup

Social constructionism wikipedia , lookup

Social history wikipedia , lookup

Cross-cultural differences in decision-making wikipedia , lookup

Origins of society wikipedia , lookup

Anthropology of development wikipedia , lookup

Social theory wikipedia , lookup

Plato's Problem wikipedia , lookup

Ethnoscience wikipedia , lookup

Sociological theory wikipedia , lookup

Epistemology wikipedia , lookup

History of the social sciences wikipedia , lookup

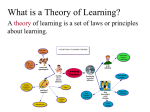

Outline for a Reflexive Epistemology Epistemology & Philosophy of Science 42(4): 46-66, 2014 Inanna Hamati-Ataya Aberystwyth University Abstract This paper addresses the notion of a “theory of knowledge” from the perspective of sociological reflexivity. What becomes of the meaning of epistemology once the ontological status of knowledge is taken seriously, and its political dimensions impossible to ignore? If the knower is no longer an impersonal, universal subject, but always a situated and purposeful actor, what kind of epistemology do we need, and what social functions can we expect it to play? Sociological reflexivity embraces the historicity and situatedness of knowledge understood as a cultural product and a social practice. It therefore enables us to cope with the collapse of our absolute and universal epistemic foundations and frames of reference, and to redefine the existential and practical meanings of knowledge for social life. In so doing, it also gives political meaning to epistemology itself, understood as a sociological theory of knowledge, not a normative one. Reflexivity can be envisaged as both a “bending back” and a “bending forward” of knowledge as praxis. As a bending back of knowledge on itself, it entails a rigorous understanding of the social conditions of possibility of our thought and our values, and hence a critical assessment of what our world-views and notions of truth owe to the social order in which we are inscribed. As a bending forward, it turns this objective understanding into an instrument of existential and social emancipation, by delineating the structural spaces of freedom and agency that allow for a meaningful and responsible scholarly practice. Introduction: Rethinking Epistemology from and for Reflexivity A common starting-point for thinking about reflexivity across the social sciences is the claim that knowledge and reality are “mutually constitutive.” This claim delineates two complementary, but not mutually inclusive, understandings of reflexive knowledge. The first informs the ontological characterization of everyday knowledge, broadly construed as including representations, opinions, and beliefs about the social world. Within Constructivism, it attributes to ordinary social agents an involvement in the “construction of” the social reality that they subjectively or phenomenologically experience as a “given,” independent order. Within Critical or hermeneutic approaches, it conveys the embeddedness of everyday knowledge in historical, economic, and cultural structures that shape, and are themselves reinforced by, individual and collective social representations. The second understanding informs the epistemological characterization of social-scientific knowledge, in the sense that it attributes to knowledge-producers qua social agents an involvement in the “construction of” the social reality that they consciously “represent” as a “constructed” order, or their embeddedness in, and hence reproduction of, historical, economic, and cultural exogenous structures. While the second understanding constitutes a logical extension of the first into the realm of science-as-special-knowledge, this logical extension is not systematically explored or operated in the social sciences, and this has significant bearing on how reflexivity is conceptualized. In the first instance, it is viewed as an ontological characteristic of social reality (generically, the “mutual constitution of structure and agency” (Giddens, 1994)), whereas in the second it translates as an epistemic principle of social-scientific research (generically, the implication of the fact that “social science is … a social construction of a social construction” (Bourdieu, 2001:172)). This paper adopts 1 the second understanding of reflexivity, which defines it as a socio-epistemic stance reflecting scholars’ critical assessment of their own knowledge, in terms of both content and practice. Within this perspective, reflexivity can be generally defined as a conscious, subject-driven “bending back” of knowledge on itself. This “bending back” can be performed at different levels and in different ways. One way of putting it is to say that reflexivity can be taken more or less seriously, or that scholars can be more or less serious about reflexivity – in other words, one can identify different types or degrees of “commitment” to reflexivity. I will focus here, albeit very briefly, on three such commitments, so as to make explicit what characterizes the one that informs the discussion offered in this paper. Two of them are, from the perspective of the third one, “minimalist.” The first “minimalist” commitment corresponds to a “bending back” of knowledge on the individual knowing subject, as a way of bringing to the surface, contra the objectivist representational creed, the experiential and contextual characteristics of the self as actor of knowledge and hence as creator or co-creator of social reality. The second “minimalist” commitment corresponds to a “bending back” of knowledge on theory as representation, in such a way that reflexivity is translated as a formal standard. The point, in this case, is to acknowledge that whatever a given social theory has to say about representation and social reality, it ought to also say it about itself – with the additional condition (which is needed against opponents’ tu quoque arguments) that such reflexivity does not render its claims logically contradictory or meaningless. More encompassing than both these types of reflexive scholarship, is the one that expresses a “maximalist” commitment to reflexivity, whereby reflexivity does not simply entail a “bending back” of knowledge on the subject, or a mere formal, logical “bending back” of truth-claims on themselves, but a “bending back” and “forward” of knowledge-as-praxis. What I mean here by “praxis” is a social practice that is governed by, produces, and expresses socio-cognitive judgments about reality. Two important components characterize the “maximalist” nature of this commitment to reflexivity: first, because knowledge is addressed as a social practice, reflexivity entails that the subject be self-objectivated as a social subject, which can only be achieved by taking into account all the conditions of possibility of her knowledge, especially the socio-historical conditions of its production; second, because knowledge is construed as being dependent on judgment for its existence and purpose, it also entails that reflexivity should be related to the production of knowledge as a purpose- and judgment-bearing form of social action. In other words, the “maximalist” commitment is philosophical and practical, cognitive and existential – it is, like all systems of thought that move from social representation to social action, properly speaking an ideology, and like all ideologies, it should be distinguished from its operating principle – reflexivity – by the appropriate “-ism” – Reflexivism. Given this particular commitment to reflexivity, a Reflexivist approach needs to define its relation to knowledge in similar terms as it defines its relation to social reality, namely, by interrogating, in both cases, not only what these objects are, but also what they socially, historically, and axiologically mean, and what it means, socially, historically, and axiologically, to be engaged in a discourse about them that is not simply representational, but praxical as well. It is, therefore, from this position that the present discussion of epistemology unfolds. The purpose is to understand what becomes of the meaning of epistemology from a Reflexivist perspective, thereby also highlighting the difference reflexivity makes to a discussion of epistemology. Knowledge Without the Cartesian Anxiety? Thinking Post Foundationalism Philosophers of (social) science and social theorists disagree over what constitutes the starting-point of a reflection on (social-)scientific research. Epistemology, as a sub-field of normative Philosophy, is itself the product of a position that considers that one should start with questions pertaining to knowledge, rather than reality. Hence the three main questions of Classical Epistemology: “what is the nature of knowledge?”, “what are the sources of knowledge?” and “what are the limits of knowledge?” These questions have preoccupied philosophers – in the Western tradition at least – since the Greek Antiquity, and most philosophical systems produced since then can be classified on 2 the basis of how they answer one or all of these questions. But there are also strong reasons for taking a different starting-point, shifting attention from epistemology (“what can we know”) to ontology (“what is”), as suggested by Roy Bhaskar (1998, 2008[1975]). The position that subtends this paper is not that epistemology should come before ontology, and the present focus on epistemology is not meant as a normative starting-point, but rather as an ontological concern. More specifically, the Reflexivist position I propose here entails looking at, and thinking about, knowledge as a privileged focus of inquiry, thereby giving it ontological priority like other approaches would give priority to gender, identity, or power. The meta-discourse from which Reflexivism addresses problems pertaining to knowledge, and to epistemology itself qua theory of knowledge, is therefore not a normative meta-discourse aiming to set standards of epistemic validity and demarcation, but a socio-historical one aiming to set standards of praxical meaning, as well as standards for purposive action. In order to make these commitments clearer, I will start with a brief review of Foundationalism to then show how Reflexivism positions itself, praxically, vis-àvis its central problématiques and those that have arisen from its collapse as a normative discourse on knowledge. This will enable me to later highlight the specifically non-normative meta-epistemic position of Reflexivism, as well as the nature of the questions that constitute its own starting-point. Foundationalism I use the term “meta-epistemic Foundationalism” to refer to what is usually called “Foundationalism” in most philosophy of social science literature. The reason for doing so is twofold. Firstly, in a general sense Foundationalism is a response to epistemic Scepticism – that knowledge is not possible (in its radical form) or that some forms of knowledge are not possible (in its moderate form). As such, it establishes the normative meaning of epistemology as “first philosophy” in the Cartesian sense, and it is therefore this grounding of the possibility of knowledge in firm “foundations” that constitutes the justification and raison d’être of (Classical) Epistemology. Foundationalism, then, is properly a meta-epistemic position, insofar as it defines the meaning, standards, and hence validity of epistemology – and epistemic discussions – as a normative reflection on knowledge. Secondly, within this meta-epistemic Foundationalism, epistemologists distinguish another Foundationalism, which is an answer to the question of what constitutes correct “justification” for knowledge-claims. This question is properly epistemic, rather than meta-epistemic, because it can only follow from the acceptance of meta-epistemic Foundationalism. Meta-epistemic Foundationalism, then, is about the foundations of knowledge, whereas epistemic Foundationalism is about the foundations of justification. Meta-epistemic Foundationalism in its modern form originates in what Richard Bernstein (1983) called the “Cartesian Anxiety.” While it is not restricted to René Descartes’ reflections on the foundations of knowledge, Descartes’ Meditations represent, for Bernstein and many other philosophers and historians, a reference-point for the establishment of Foundationalism in Western philosophy and classical Epistemology, not least because it responds to Descartes’ own skepticism. The Cartesian Anxiety refers to the need to ground the possibility of knowledge in firm, certain foundations or, according to Descartes’ own analogy, to establish an Archimedean epistemic point of reference: Archimedes, in order that he might draw the terrestrial globe out of its place, and transport it elsewhere, demanded only that one point should be fixed and immovable; in the same way I shall have the right to conceive of high hopes if I am happy enough to discover one thing only which is certain and indubitable. (Descartes, 1996:63) That Descartes’ cogito (“I think therefore I am”) could only fully acquire its axiomatic epistemic power through a logical-deductive demonstration of the existence of God as a “perfect being” incapable of systematically deceiving a man who applies his reason with the utmost methodological rigor, is only secondary to our concern here. The important point is that the cogito established an 3 Archimedean starting-point, not just for knowledge itself (from a Foundationalist perspective) but also for a long-lasting tradition in the philosophy of knowledge, which Richard Rorty (1979) critiqued as the “truth as correspondence” theory of knowledge, and which is central to Foundationalism itself. Put in simplified terms, meta-epistemic Foundationalism is the belief that human knowledge is possible, that this possibility originates from a human built-in ability to distinguish truth from error, falsity, and opinion, and that truth is born out of the rigorous confrontation of a rational subject with an independently existing phenomenal world of which it is possible to produce statements or truth-claims of a universal validity – and “universal validity” means, in this case, not a validity resulting from an “inter-subjective” agreement among subjects of knowledge who might come to similar conclusions because of similar cognitive, cultural, or other biases, but resulting from an equal ability to “recognize” the independently objective “truth” of the external world. In Classical, and more specifically “analytic” Epistemology, meta-epistemic Foundationalism leads to defining knowledge as “justified true belief” – an idea that goes as far back as Plato’s exposition of the meaning of true knowledge in his Theaetetus – which is often referred to as the “standard analysis” of knowledge. This idea is at the origin of “mainstream” Epistemology, which has traditionally been concerned with propositional knowledge (knowledge about things or knowledge that) rather than knowledge by acquaintance (knowledge of things), self-knowledge, or knowledge how. This focus on propositional knowledge rests on the assumption that the proposition is both “the principal form in which reality becomes understandable to the human mind” and “the form in which knowledge is communicated” to others (Zagzebski, 1999:92). It follows that Classical Epistemology is mainly interested in knowledge as a state of being that connects the subject to reality through a true proposition. Accordingly, the statement “S (the subject of knowledge) knows that p (the proposition)” is valid if and only if (a) S believes that p; (b) p is true; and (c) S is justified in believing that p1. Epistemic Foundationalism, then, aims to set the standards for what constitutes valid “justification” of “true beliefs.” It posits that a system of valid truth-claims can be divided into a “foundation” and a “superstructure,” whereby the justification of the beliefs belonging to the latter (nonbasic beliefs) is dependent on the justified beliefs of the former (basic beliefs). What makes basic beliefs justified is precisely the answer that different epistemic philosophies attempt to offer: basic beliefs are immediately or directly justified, either because they are based on experience (Empiricism), or because they are self-justified (Rationalism), or acquired through a reliable inference process (Inductivism/Deductivism, etc.). Non-basic beliefs, on the other hand, are mediately or indirectly justified by their dependence on basic beliefs. The Cartesian Anxiety that is at the origin of meta-epistemic Foundationalism starts from Descartes’ skepticism about epistemic Foundationalism – Descartes’ journey from the cogito to God is chronologically a journey from the establishment of epistemic Foundationalism to that of meta-epistemic Foundationalism, which aims to logically ground the former in the latter. The cogito is his answer to what grounds knowledge-claims in certain truth, like most Rationalisms that have preceded or succeeded it. Incidentally, Descartes’ doubts about the validity of the cogito delineates an alternative, non-Foundationalist view of justification, known as Coherentism. Against the pyramidal model proposed by epistemic Foundationalism, Coherentism proposes the analogy of the web, whereby specific beliefs are justified by their coherent place in a system of beliefs, which becomes the unit of epistemic assessment instead of the individual basic beliefs of epistemic Foundationalism. The coherence of the system itself is determined by how well it “hangs together,” that is, how well its component beliefs fit together on the basis of “inferential, evidential, and explanatory relations” (BonJour, 1985). Coherence theories of knowledge are therefore holistic in the sense that they associate justification not merely with specific evidence, but with the shared and coherent background system that gives such evidence its full meaning. From a Foundationalist perspective, 1 The “standard analysis” was famously challenged by Edmund Gettier in a three-page essay entitled “Is Justified True Belief Knowledge?” (Gettier, 1963), which has led Epistemologists to try to amend the “standard analysis” so that it could address “Gettier-cases,” i.e., the type of counterexamples Gettier opposed to it. 4 Coherentism is deficient because, as shown by Descartes’ own skepticism about the “reality” that presented itself to him in dreams, the overall coherence of a system of representations can never guarantee that our perceptions of the world are real and true, or that the world itself exists at all, because it is possible to have a coherent system of beliefs that “hangs together” well but that is wholly false – which is precisely what Descartes’ idea of an “evil deceiver” was meant to illustrate. Critiques of Foundationalism The purpose of this section is not to present an exhaustive list of all critiques of Foundationalism, because it is not merely the content of these critiques that interests me here. The purpose is rather to highlight the angles and premises from which these critiques are formulated, and their consequent implications for thinking about knowledge without or against Foundationalism – and without or against the Cartesian Anxiety itself. Taking Descartes’ own journey from Skepticism to Foundationalism as a reference-point, Analytic Epistemology has revisited the “evil deceiver” analogy in an attempt to find more convincing foundations at the epistemic level of inquiry (i.e., alternatives to the cogito and, implicitly, to God as well). Symptomatically, but unsurprisingly, this journey also takes as a starting point the epistemic, rather than the meta-epistemic problem that Descartes identified – and this is unsurprising because, as Rorty notes, Epistemology itself understood as “first philosophy” cannot interrogate meta-epistemic Foundationalism without undermining its own existence. In its contemporary version, the “evil deceiver” hypothesis takes the form of the “brain-in-avat” (BIV) argument, and goes as follows: (a) You know that p if you know that you are not a brain in a vat; (b) You do not know that you are not a brain in a vat; (c) Therefore, you do not know that p. To this author’s knowledge, no successful or consensual resolution to the BIV problem has yet been found within Analytic Epistemology. This explains why epistemic Skepticism is still alive and kicking today, and paradoxically, why Classical Epistemology is too, insofar as its raison d’être is to (attempt to) provide renewed answers to Skepticism. Interestingly, a possible “resolution” of the BIV challenge comes from the perspective of a Pragmatist, not Foundationalist, theory of knowledge. Against the representational view that has historically constituted the central position of Foundationalism, whereby truth depends on a correspondence between mind and objects in reality, Pragmatism considers that truth depends on a causal connection between words and referents. This important difference replaces, so to speak, the “meaning of logic” so characteristic of Analytic philosophy, with a “logic of meaning.” Pragmatist philosopher Hilary Putnam (1981) suggested a version of the BIV scenario wherein the envatted brain(s) would exist with no external “programmer” (or evil deceiver), and considered the meaning of “being-a-brain-in-a-vat” as posited from a first-person viewpoint, in accordance with Descartes’ own subjectively experienced skepticism. From this perspective, the meaning of the sentence “I am a brain in a vat” will be different based on whether I am or not an envatted brain. If I am not, the sentence is “false” because of its meaning in the real world of real human beings. If I am, then there is no causal connection between the words I use and my experience of the objects they refer to (“I,” “brain,” “vat,” but also the notion of being “in something”, etc.). In both cases, then, the utterance is “false,” and radical skepticism is defeated. In other words, the whole BIV problem is meaningless. Other critics of Foundationalism similarly focus on the representational view. One could cite, among others, John Dewey’s (1929) critique of the “Spectator Theory of Knowledge,” Wilfrid Sellars’ (1963) critique of the “Myth of the Given,” and W.V. Quine’s (1951) critique of the “Dogmas of Empiricism.” These criticisms have more generally led to what is referred to as the “death of Epistemology” movement, which includes two particularly interesting attacks. The first is embodied in Quine’s proposal to replace Classical Epistemology with Naturalized Epistemology. This is an important critique because it touches the very “foundations” of Epistemology as a normative philosophical project, that is, the fact that Epistemology claims to provide foundations for all other cognitive inquiries, especially those addressed by the “sciences.” The meaning of Epistemol5 ogy as “first philosophy” therefore rests on the idea that epistemic questions are necessarily independent of and prior to scientific ones. Naturalized Epistemology (Quine, 1969) challenges this Cartesian view by positing that Epistemology’s objective should be to understand how human beings actually reach beliefs about the real world, and such a question can only be answered by relying on the empirical sciences themselves. By replacing the normative questions of Classical Epistemology with the empirical questions of the natural sciences, Quine thereby also reframes the classical debate between meta-epistemic Foundationalism and Skepticism, pointing to the fact that skepticism itself results from the empirical observations men make of the discrepancies between the content of their beliefs as they construct them, and the nature of reality as they understand it through empirical, scientific knowledge. On this view, the “problems” of Epistemology should be replaced with those of experimental, Cognitive Psychology. A similar, but historical, critique of Epistemology qua “first philosophy” was proposed by Rorty in his analysis of the framework that subtends the “correspondence-theory-of-truth,” namely, the system wherein mind, perception, and language “mirror” a man-independent reality, which has provided the core discussion between Foundationalism and Skepticism. For Rorty, Epistemology can be construed as a historically constituted cognitive ideology that functions as a “normal philosophy” in the sense used by Thomas Kuhn (1962) for “normal science”: it performs an essentially pragmatic, rather than foundational function, that is meaningful only within the boundaries of its historicity. By approaching the “theory of knowledge” as a historical intellectual construct, one is led to abandon the idea that Epistemology itself is necessary, since its central “problems” are no longer viewed as perennial, foundational, or necessary for the development of different forms of knowledge. This also leads Rorty to question the very nature of Philosophy as a professionalized discipline that allocates to itself the privilege of judging the validity and nature of other forms of cultural production, including science, ethics, art, and religion. Parallel to the “death of epistemology” movement is a series of “sociological” critiques of Epistemology that are informed by a wide variety of social philosophies, themselves grounded in what is usually referred to as the “Continental” tradition. These critiques stress the conditions of the production of knowledge and how these impact the core assumptions and problems of Epistemology. By and large, they operate a significant shift of the epistemological focus of inquiry from the question “what knowledge?” to “whose knowledge?” Through this lens, Epistemology’s universal claims about the nature, sources, and standards of knowledge are viewed as embodying the particularistic perspectives of a specific social group that occupies a privileged position of power through history. By perpetuating the classical normative approach to epistemic questions, the discipline itself is viewed as maintaining and reproducing the structures of domination and oppression this group exerts on the rest of society. It is the Bourgeoisie’s oppression of the Proletariat for Marxist epistemologists, who focus on the socio-economic grounding of the classical theory of knowledge; men’s oppression of women for Feminist epistemologists, who stress on the “androcentric” assumptions of classical Epistemology; and the “White” man’s oppression of subjugated races for Black epistemologists – and by extension, “Western” philosophy’s biases, for Post-Colonial scholars. The cognitive preoccupations of these alternative, critical Epistemologies are more akin to those of social theory than to Epistemology proper. They converge more specifically with the Sociology of Knowledge, which aims to objectively reveal the social conditions that subtend the production of knowledge as a socio-historical phenomenon produced by real subjects in historically defined social contexts, rather than by an abstract homo epistemicus endowed with universal, immutable, a priori faculties. The sociology of knowledge, in its Mannheimian origins (Mannheim, 1936), itself originates in a different tradition that philosophers since Bertrand Russell have taken the habit of calling “Continental,” as opposed to the “Analytic” tradition. What epistemic discussions owe to the “Continent” are two related shifts – largely grounded in Hegelian thought (Hegel, 1977). The first is a shift from the individual subject of knowledge to the collective subject – culture, society, social class, gender, and so on; the second is a shift from the normative to the historical, that is, from a discussion of the standards of validity to one of the conditions of possibility and meaning of knowledge(s). 6 The confrontation of historical and normative perspectives on knowledge, as well as its consequences and implications, are at the heart of the “rupture” that characterizes the Western reflection on “modernity” and “post-modernity,” which has affected all social sciences. A historical – rather than conceptual – review of the literature produced since the turn of the twentieth century, and of its effects since the second half of that century, is enough to give a sense of the “trauma” that accompanied the critique of Foundationalism and its constitutive views. Epistemic Relativism and epistemic Nihilism have indeed proven to be as problematic as epistemic (or even meta-epistemic) Skepticism, not because of their logical power, but because they are socio-politically and culturally more devastating. In other words, what the critique of Foundationalism allows is a return of the Cartesian Anxiety not simply as an epistemic threat, but as an existential one. This threat no longer succumbs to the hierarchy of the sciences – and hence to the authority of epistemology and of the philosophy of science as an arbiter in the conflicts that oppose contending views within the social sciences: the latter can quite comfortably sustain their anxieties while acknowledging that the approximate certainties of physics are quite successful in turning man into a “master of nature” as Descartes and Bacon hoped he would. But the problems of certainty become different when knowledge becomes historical and social, and when it is historical and social knowledge that one needs in order to speak of (one’s place in) the world and act in it. Reflexivity as we understand it today, then, originates in this reflection on knowledge that converges with social critiques of epistemology. But reflexivity is defined by more than just a reflection on knowledge – whether philosophical-normative or socio-historical. It is equivalent neither to the kind of journey that led Descartes to reflect on his own knowledge, nor to the sociology of knowledge/science as an objectivation of the conditions of possibility of social knowledge. Reflexivity entails, however, “doing” something with both these reflections, and more importantly, perhaps, it should entail “doing” something tout court: while it is easy to become trapped in the logical circularity of reflexive thought, or in the paralyzing loss of foundations that follows from the acknowledgment of the historicity of reason, knowledge, truth and validity, reflexivity is meaningless conceptually if it is socio-cognitively so. The Positive Anxieties of Post-Foundationalism The implications of the shift from logic to meaning and from the normative to the historical illustrate the extent to which the value of Foundationalism is only partially conveyed in discussions of epistemology. Its full value lies in its ability to appease not simply a doubt as to humanity’s ability to know the world, but a doubt as to its ability to situate itself in it. Bernstein himself saw in the Meditations a response to scepticism not merely as an epistemic problem, but more importantly as an existential one: It is the quest for some fixed point, some stable rock upon which we can secure our lives against the vicissitudes that constantly threaten us. The spectre that hovers in the background of [Descartes’] journey is not just radical epistemological skepticism but the dread of madness and chaos where nothing is fixed, where we can neither touch bottom nor support ourselves on the surface… Either there is some support for our being, a fixed foundation for our knowledge, or we cannot escape the forces of darkness that envelop us with madness. (Bernstein, 1983:18) If the loss of Foundation(alism) leads not simply to ignorance, but to chaos, then it becomes necessary to interrogate the social function of epistemology and the socially disciplining power of a “theory of knowledge,” understood as a discourse that has the ability to establish social order by setting the standards for what counts as valid representations of the social world. In this sense, “madness” is “subversion”: a subversion of order, denounced as a subversion of reason. For a knowledge-producer to be reflexive, then, means to address epistemology as a social phenomenon, and therefore start with a socioanalytical, rather than analytical or normative, meta-epistemology. 7 This entails interrogating the social “stakes” of epistemic discussions and standards, which are, whether one wants it or not, an intrinsic component of all knowledge-production: Understood as the effort whereby social science, taking itself for its object, uses its own weapons to understand and check itself, … [reflexivity] is not a matter of pursuing a new form of absolute knowledge, but of exercising a specific form of epistemological vigilance, the very form that this vigilance must take in an area where the epistemological obstacles are first and foremost social obstacles. (Bourdieu, 2004:89; emphasis added). This view of reflexivity, however, is itself only partial, insofar as it locates reflexivity at the methodological level of inquiry. To complete it, one needs to also interrogate epistemology not merely as a normative system or as a discourse, but more essentially as a social practice: that of knowledge-producers who are social agents immersed in social structures wherein cognitive stakes are social stakes, and who, by engaging in representations of reality, are themselves performing a social act that constantly needs to be evaluated. As Pierre Bourdieu shows, self-understanding is not merely part of social understanding: it is at once an epistemic, a methodological, and a social requirement. Without the social – and even political – function of reflexivity, the “problem of reflexivity” manifests itself as a formal loop, a circle that might give the solipsist illusion of achieving epistemic self-sufficiency at the expense of both socio-historical meaning and social purpose, or lead to a praxical paralysis. As Gramsci puts it: If the philosophy of praxis affirms theoretically that every “truth” believed to be eternal and absolute has had practical origins and has represented a “provisional” value (historicity of every conception of the world and of life), it is still very difficult to make people grasp “practically” that such an interpretation is valid also for the philosophy of praxis itself, without in so doing shaking the convictions that are necessary for action. (Antonio Gramsci, 1971:750) In other words, reflexivity has to entail a “bending forward” just as much as a “bending back” of knowledge. Within Foundationalism, the “bending forward” of knowledge was subtended by the Cartesian Anxiety as a need to avoid chaos. Reflexivism, then, needs to replace the Cartesian Anxiety with another “anxiety” whose positivity could serve as an equally constitutive and normative stimulant for sustaining reflexivity both as a “bending back” and a “bending forward” of knowledge-as-praxis toward knowledge-as-praxis. And this entails asking a different set of questions, of which the paramount question is “what do we need epistemology for?” The Difference(s) Reflexivity Makes: A Praxical Engagement with the Problem of Knowledge The first part of this paper announced that the present endeavor does not rest on a commitment to start from epistemology rather than ontology, and that the focus on knowledge was meant as an ontological priority. This claim means that Reflexivism as defined here rests on a theory of knowledge-as-reality rather than a theory of knowledge-as-norm. In other words, if one does not need to start from a theory of knowledge in its classical understanding, one does not need normative epistemology at all. This seems to suggest that “Why do we need epistemology?” should not be included in the questions of Reflexivist research. If, however, epistemology itself is a social phenomenon, then it is part of “what is” and should constitute an important ontological concern for Reflexivism. But this also means that “Why do we need epistemology?” is not understood as a normative but as a sociological question, which interrogates the social value, meaning, and function of a theory of knowledge for the constitution and functioning of social reality. The Reflexivist’s “why” is therefore different from the (Foundationalist) epistemologist’s “why,” and the very meaning of “a 8 theory of knowledge” is completely modified within Reflexivism, because it becomes part of “a theory of reality” rather than “a theory of what constitutes knowledge of reality” in the normative sense. In other words, “why do we need epistemology” follows from the question “what does epistemology do.” But this ontological concern is obviously not specific to Reflexivism. What is specific to it is the reflexive requirement that an answer to such a question be turned back toward the subject of knowledge, in two different but complementary ways. First, an understanding of the social function of epistemology is necessary, as Bourdieu’s quote illustrates, as “epistemological vigilance,” that is, as a methodological parameter of social-scientific research; secondly, it is necessary in order to guide and push “forward” the production of knowledge about social reality. A research agenda guided by these two dynamic inquiries opens up – or breaks – the circularity of reflexive thought, turning it into a forward-pointing “spiral,” thereby guaranteeing that the process of knowing is constantly reassessed in the act of producing knowledge, i.e., that the gains of “already-made-science” are mobilized and reinvested into the production of “science-in-the-making,” so that the latter is constantly informed by, and assessed through, the former (Bourdieu, 1990:28; Bourdieu, Chamboredon and Passeron, 1983[1968]:20). In short, a Reflexivist research is governed by two primordial questions, namely, “what do we know about knowledge?” and “what do we want from knowledge?” I will address these two questions to show what makes them central to the Reflexivist project – and hence what differentiates Reflexivism from a traditional engagement with epistemology – and how they are interrelated. Knowledge as Ontology: Implications of the Socio-historical Turn Away from Normative Epistemology The shift away from normative epistemology corresponds to a displacement of the question about knowledge from an inquiry into its normative standards of validity to an inquiry into its empirical conditions of possibility. While these undoubtedly include natural conditions, as suggested by Quine, sociological reflexivity is more specifically concerned with the social conditions of possibility of knowledge. In other words, if “epistemology” is to have any meaning within a Reflexivist sociological approach, it should be that of a “socialized” epistemology (or “social epistemology” as coined by Steve Fuller (1988)). And as mentioned before, this follows logically from a conceptualization of epistemology itself as a “social” phenomenon. A socialized epistemology, then, is a “sociological theory of knowledge.” But reflexivity being a principle of social-scientific research, it is specifically concerned with “sociological knowledge,” which means therefore that socialized epistemology is a “sociological theory of sociological knowledge,” a theory that is consistent with the view of social science as a “social construction of a social construction.” This theory is “the system of principles that define the conditions of possibility of all the properly sociological acts and discourses” produced in the course of social-scientific research (Bourdieu, Chamboredon, and Passeron, 1983[1968]:15; my translation). This shift has two implications. The first is that although it rejects the subjection of ontology to epistemology, it retains the primacy of (social-scientific) knowledge as a focus of inquiry. As Bourdieu et al. note, [t]he question of the affiliation of a sociological research to a particular theory of the social, that of Marx, of Weber, or of Durkheim, for example, is always secondary to the question of its belonging to sociological science: the only criterion of this belonging lies indeed in the application of the fundamental principles of the theory of sociological knowledge which, as such, does not in any way separate authors that everything separates on the terrain of the theory of the social system (Bourdieu, Chamboredon and Passeron, 1983[1968]:15-16; my translation; emphasis added). 9 I will say more about this point in the following section, but it is necessary to add here that it takes its full meaning when one adopts a praxeological approach to social-scientific research, that is, when one addresses it as a special social instance of social knowledge that is produced by a specific social group as a specific form of social action. Reflexivism, in other words, takes as its ontological starting-point the social, existential, and moral situation of knowledge-producers as professionals, which is why, as will be explained later, it presents itself as a socio-cognitive “ideology.” The second implication is that a Reflexivist approach to epistemology, which aims to objectivate knowledge socio-historically, knows that it necessarily objectivates it from a given sociohistorical perspective. This, in turn, means two things. First, that a socialized epistemology rests on no “foundations” except reflexivity understood as a constant process of sociological evaluation of the instruments of knowledge, through a bending back on the very process of knowledgeproduction that mobilizes the partial, approximate “truths” gained through socio-historical analysis. This extracts reflexivity from the malaise of Nihilism and extreme Relativism, as long as one is willing to accept that knowledge is always historical (and therefore that “justification” will rest on a Coherentist rather than a Foundationalist epistemology), and willing to draw some meaningful, empowering conclusions out of this “fact.” Secondly, it means that while Reflexivism cannot adhere to an objectivist understanding of objectivity, it can equally not be content with a constructivist notion of objectivity as “inter-subjective agreement,” at least not as far as the concrete, social aspects of the constitution, meaning, and effects of this agreement are concerned. And this is so because the acknowledgment of the “inter-subjective” nature of social truths does not end the problem of normative epistemology and does not constitute a sufficient closure to the critique of Foundationalism and Positivism. On the contrary, it opens up epistemic discussions to new problems and new “anxieties” that social-scientific research has to strive to address, and Reflexivism turns these problems and anxieties into positive values for research as a socio-cognitive and moral praxis. More specifically, what is at stake in the problem of “inter-subjective agreement” are its own conditions of possibility, but also its social effects and efficacy. Insofar as this agreement is, socially and politically speaking, a social consensus, and insofar as claims about social reality are themselves political acts, social scientists cannot be oblivious to the disciplining effect of their own production, or to what this production owes to their position in, and viewpoint on, the social world – even more so when it turns into a consensus among them as a social group. A Reflexivist approach is therefore fundamentally concerned with the simultaneous and complementary objectivation of the rules, methods, and meanings that govern the production of knowledge – not least the most consensual ones within the scientific community – as well as the social effects of the representations and values that they produce. Far, then, from being antithetical to cognitive “progress,” the break with Foundationalism is in fact a requirement for its achievement, because Foundationalism itself induces us into “error”: the error that is the ignorance of what makes our knowledge possible, and socially meaningful and efficient, and of the socially “creative” power of a knowledge that claims a mere “representational” power over “reality.” Generally, this means that a Reflexivist approach is necessarily “critical” in the traditional sense of the term, but also “polemical” in the sense that it constitutes itself into a systematic, socially “dissident” practice within social science, for “a social science armed with the scientific knowledge of its social determinations constitutes the most powerful weapon against ‘normal science’,” and especially “against the positivist confidence, which represents the fiercest social obstacle to the progress of science” (Bourdieu, 1990:47). But if Positivism is today’s “normal science,” it might not be tomorrow’s, and Reflexivism is necessarily committed to a permanent critique of any emergent socio-cognitive consensus – if only because such a critique allows to improve it by mobilizing any new sociological understanding of knowledge and of its conditions of possibility, and thereby further “rectify” the “truths” that constitute the operating principles, and those that subtend the social efficacy, of this new consensus. From this perspective, the sociology of knowledge, and of knowledge-producers, is a central and built-in requirement of a Reflexivist research programme and curriculum. It entails that the conditions of possibility of knowledge, and especially the condi- 10 tions of its production, be objectivated at all relevant levels: socio-political, academic, institutional, and individual/personal. Knowledge as Praxis: Implications of the Centrality of Judgment If the first shift operated by Reflexivism concerns a displacement of the “what” question from the investigation of the normative standards of validity of knowledge to the investigation of its social conditions of possibility (and of its conditions of social meaningfulness), the second shift is manifested in a more purposive question, namely, “what do we need epistemology for?” Within Foundationalism, there is no room for such a question, simply because knowledge is endowed with an intrinsic (positive) value, that grants it simultaneously a social and moral validity. But as the social and political meaning of knowledge comes to the forefront, and as we come to terms with the idea that knowledge is never absolutely objective, true, valid, and neutral, but always expressive of given socio-historical perspectives, values, interests, and concerns, then the value of knowledge becomes more problematic. More specifically, a socio-historical approach to knowledge requires that we answer the question: “what do we want from knowledge,” and by extension, “what do want from epistemology,” or “what do we expect from a theory of knowledge.” This question is important when knowledge is viewed not merely as a “thing” we acquire and use, but as a “practice,” a practice that also “does things,” since it is both performed and performative. An exhaustive formulation of this question and of possible answers to it from a Reflexivist perspective entails the reintroduction into epistemic inquiry of judgment and values, which have been systematically left out of the representational view of knowledge on the basis that they obstruct the achievement of “objectivity” by introducing bias, subjectivity, opinion, and error. As we better understand the social nature of knowledge and the social constraints and conditions that govern its production, meaning, and effects, the ruling out of judgment and values itself becomes a source of error, an epistemic fallacy. But instead of constituting a backward move toward the subjectivity of “lived experience,” “spontaneous sociology,” or “ideology-as-distorted-consciousness” the reintroduction of judgment and values – i.e., of the “axiological” – itself needs to be subjected to a socio-historical analysis. What becomes an object of Reflexivism is the empirical ways wherein individual and collective interests, preferences, perspectives, and perceptions inform the constitution of knowledge and the very mechanisms of the production of knowledge at all levels of the scientific process. And because Reflexivism gives ontological priority to social-scientific knowledge, the sociology of knowledge that constitutes the core of Reflexivist research needs to give ontological priority to the axiological component of scholarly practice, as part of the “bending back” of knowledge on the knowing subject. But beyond this axiological “what” of ontology, Reflexivism also entails to reflexively acknowledge that this objectivation does not erase the effects of judgment from scholarly praxis – precisely because judgment is always constitutive of praxis – but is itself reliant on them for purpose and meaning. In order to move beyond reflexivity as a circular loop, Reflexivism needs to define its own scholarly practice in accordance with its empirical nature, and hence set for itself explicit values for a “bending forward” of knowledge-as-praxis. These can only be established in relation to social problems and problématiques, which are themselves necessarily temporary and historical, and therefore need to constantly be assessed in order to avoid any dogmatic and un-reflexive scholarly ethos. I have, elsewhere (Hamati-Ataya, 2011), offered a Reflexivist perspective on the relation between knowledge and judgment. I have highlighted the fact that this engagement with the question of power from a Reflexivist perspective does not necessarily entail adopting an “emancipatory” commitment, and should in fact avoid any such commitment that does not reflexively interrogate its own historicity and its grounding in conceptual and cultural specificities. But such an emancipatory ethos is one possible choice among many others. What I wish to focus on more specifically here is what distinguishes Reflexivism from other approaches that explicitly adhere to an activist social 11 attitude, such as Critical Theory, Critical/Radical Constructivism, or (some forms of) Feminism. Reflexivism’s starting-point is the specific social condition/situation of scholars qua scholars. It does not merely extend the social properties of everyday knowledge, representations, and beliefs of ordinary social agents to a particular social group, but rather starts from the particularity of scholars as a social group whose praxis is qualitatively different from that of other social groups, and whose position, impact and responsibility in society need to be interrogated on the basis of this specificity. In other words, Reflexivism is not a general system of thought that aims, in its turn, to be expanded to everyday knowledge or help ordinary social agents make sense of their world. While it aims to produce such a generally meaningful knowledge about the social world, its operating principle – reflexivity – is a specific parameter that makes sense, and is meaningful, only when viewed from the perspective of the social scientist as knowledge-producer. In this sense, it is more specifically tailored than other “critical” approaches to the problématiques that are specific to the scholarly viewpoint and condition, because part of what motivates this reflection on reflexivity and Reflexivism is precisely a preoccupation with these very peculiar existential problématiques that scholars in the social sciences hardly share with any other social group – although other social groups (journalists, artists, politicians) can equally produce similar particularistic modes of knowing-being that are grounded in their own social condition and that are guided by a specific reflection on their social responsibilities. The difference, therefore, between Reflexivism and other traditions is that Reflexivism aims to function as a socio-cognitive “ideology,” which reconciles the theory of knowledge with the constraints of knowledge-production as well as the requirements of social action, thereby pursuing a maximalist commitment to reflexivity that avoids the trap of logical circularity and loss of meaning, while grounding the scholarly ethos in a modest – realistic – but consistent understanding of the social determinants and possibilities of knowledge. Perhaps more than any other scholar, Bourdieu managed to use reflexivity as an instrument of epistemic vigilance and self-understanding, but also to translate it into a positive axiological vector for praxis. In his own reflexive project and throughout his scholarly trajectory, the “bending back” and “forward” of knowledge manifests itself as a clear socio-cognitive “ideology,” capable of reconciling knowledge-claims with both their conditions of possibility and their social responsibilities: [a knowledge of the mechanisms that govern the intellectual world should] teach [scholars] to locate their responsibilities where their liberties really are, and to obstinately refuse the coward attitudes … that abandon to social necessity all its force, to fight in oneself and in others the opportunist indifferentism or the blasé conformism that grants the social world what it demands, all the little nothings of resigned complacency and of subdued complicity. (Bourdieu, 1990:14-15). All social scientists have something to say about the world that involves them and others, and that springs from the peculiar position they occupy in that social space that constitutes simultaneously their object of study and their sphere of action. A move away from Foundationalist, Objectivist, and Positivist social science can be a move toward many different things – including a complete indifference to what becomes of the meaning of knowledge and values, or a narcissistic return to the self as the sole repository of meaning. The difference reflexivity makes to such a move is first and foremost a commitment to asking different questions about knowledge and scholarly praxis, without imposing any other condition than a consistent, responsible, and socially useful self-understanding grounded in the social reality of the position wherefrom it is produced, and driven by a concern for what this position, in turn, has to offer reality. 12 Conclusion: After Social Epistemology: Beyond the Culture/Nature Divide A socialized, and hence social, epistemology is the only coherent framework for the pursuit of a meaningful “theory of knowledge.” It is also the only framework that enables us to both face and transcend the political, existential, and moral dilemmas that the historicity of our thought and judgment imposes on us. Within this reflexive understanding of knowledge as cultural product, and of knowing as a social practice, “the demarcation problem” of classical epistemology shifts onto a different plane: what now needs to be demarcated is not the difference between truth and falsity/error/opinion, but that between different types of social meaningfulness in the realm of judgment and action. To choose reflexivity is to wager that a deeper understanding of the conditions of possibility of our thought and practice can help us understand their social meaning and efficacy; that an objective understanding of how we are from the world can help us better orient ourselves in the world. But beyond the socio-historical conditions of possibility of our knowledge and values, reflexivity also enjoins us to interrogate their non-social, natural conditions of possibility, a project that finds its basic rationale in Quine’s preliminary delineation of “naturalised epistemology.” However, once it has been socialised and naturalised, epistemology should develop into a comprehensive reflexive theory of knowledge that takes into account the very connection between society/culture and nature, as well as their evolving co-constitutiveness. There was a time when the sociology of knowledge was not yet subjected to the political correctness that characterises our own era, and when it could ask bold questions about the natural, environmental (ecological), and material origins and factors shaping the cultural characteristics of different human communities, including their religious, artistic, or scientific traditions. In doing so, it implicitly or explicitly denied the idealist view that “science” was unique and universal in its features, standards, and authority, as well as the idealist view that knowing was the self-contained and innate ability of a universal, impersonal “subject.” Before this line of inquiry has even begun to reassert itself in contemporary sociology of knowledge, science itself seems to be hinting at the closing of the nature-culture gap from the other direction. The time has already come for the biological and physiological structures of “cognition” to be hypothesised as not simply following their own, “natural” laws of evolution, but as potentially affected by the cultural and social facts and processes of human collective life. Just as child education affects child development, just as emotional, physical, and linguistic experiences affect the development of neurological pathways and the establishment of long-lasting structures of human adult behaviour, we might be soon discovering the impact of (different) social practices on (differentiated) physiological evolutionary paths. What if specific modes of social organisation, or specific collective experiences enabled the transmission of specific emotional, perceptual, ethical and/or cognitive dispositions? It is with such questions in mind that a reflexive theory of knowledge should be developed. A theory of knowledge that can help us understand the civilisational conditions under which our spaces of cognitive possibilities either expand into wider and more diverse cultural horizons, or collapse under the weight of uniformity and the hegemony of specific forms of social organisation. Whatever the future holds, it is obvious that we are moving toward the discovery of a wider realm of contingency, historicity, and relativity. Classical epistemology can survive in such an environment only because it is unaffected by this world - such survival is that of the blessed madman. But those for whom blissful ignorance is not an option, epistemology can still be meaningful if its essentially political nature is embraced, and if it is pursued as a political - and hence socially accountable - praxis. Bibliography Bernstein, Richard (1983) Beyond Objectivism and Relativism: Science, Hermeneutics, and Praxis. Philadelphia: University of Philadelphia Press. 13 Bhaskar, Roy (1998) “General Introduction” in Critical Realism. Essential Readings, edited by Margaret Archer, Roy Bhaskar, Andrew Collier, Tony Lawson, and Alan Norrie, pp. ix-xxiv. New York: Routledge. Bhaskar, Roy (2008[1975]) A Realist Theory of Science. London: Verso. BonJour, Laurence (1985) The Structure of Empirical Knowledge. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. Bourdieu, Pierre (1990) Homo Academicus. Paris: Minuit. Bourdieu, Pierre (2001) Science de la science et réflexivité. Paris: Raisons d’Agir. Bourdieu, Pierre (2004) Science of Science and Reflexivity. Cambridge: Polity Press. Bourdieu, Pierre, Jean-Claude Chamboredon, and Jean-Claude Passeron (1983[1968]) Le métier de sociologue: Préalables épistémologiques, 4th edition. Paris: Mouton. Descartes, René (1996) Discourse on Method and Meditations on First Philosophy. New Haven: Yale University Press. Dewey, John (1929) The Quest for Certainty: A Study of the Relation of Knowledge to Action. New York: Minton, Balch. Fuller, Steve (1988) Social Epistemology. Indiana University Press. Gettier, Edmund (1963) Is Justified True Belief Knowledge? Analysis 23:121-3. Giddens, Anthony (1994) The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration. Cambridge: Polity Press. Gramsci, Antonio (1971) Selections from the Prison Notebooks of Antonio Gramsci, edited and translated by Quentin Hoare and Geoffrey Nowell Smith. London: Lawrence and Wishart. Hamati-Ataya, Inanna (2011) The “Problem of Values” and International Relations Scholarship: From Applied Reflexivity to Reflexivism. International Studies Review 13(2):259-287. Hegel, Georg W.F. (1977) Phenomenology of Spirit. Translated by A.V. Miller. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Kuhn, Thomas (1962) The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Mannheim, Karl (1936) Ideology and Utopia: An Introduction to the Sociology of Knowledge. New York: Harvest. Putnam, Hilary (1981) Reason, Truth, History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Quine, W.V. (1951) Two Dogmas of Empiricism. The Philosophical Review 60:20-43. 14 Quine, W.V. (1969) Ontological Relativity and Other Essays. New York: Columbia University Press. Rorty, Richard (1979) Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Sellars, Wilfrid (1963) “Empiricism and the Philosophy of Mind” in Science, Perception and Reality, pp. 127-96. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. Zagzebski, Linda (1999) “What is Knowledge?” in The Blackwell Guide to Epistemology, edited by John Greco and Ernest Sosa, pp. 92-116. Oxford: Blackwell. 15