* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Document

Udmurt grammar wikipedia , lookup

Old Irish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Modern Greek grammar wikipedia , lookup

Navajo grammar wikipedia , lookup

Arabic grammar wikipedia , lookup

Lithuanian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Zulu grammar wikipedia , lookup

Macedonian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Preposition and postposition wikipedia , lookup

Malay grammar wikipedia , lookup

Lexical semantics wikipedia , lookup

Old English grammar wikipedia , lookup

Scottish Gaelic grammar wikipedia , lookup

Swedish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Esperanto grammar wikipedia , lookup

Ancient Greek grammar wikipedia , lookup

Georgian grammar wikipedia , lookup

English clause syntax wikipedia , lookup

Japanese grammar wikipedia , lookup

Romanian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Portuguese grammar wikipedia , lookup

Kannada grammar wikipedia , lookup

Italian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Russian grammar wikipedia , lookup

French grammar wikipedia , lookup

Modern Hebrew grammar wikipedia , lookup

Chinese grammar wikipedia , lookup

Serbo-Croatian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Turkish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Yiddish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Icelandic grammar wikipedia , lookup

Dutch grammar wikipedia , lookup

Polish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Latin syntax wikipedia , lookup

Spanish grammar wikipedia , lookup

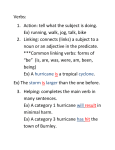

1. GRAMMATICAL STRUCTURE 1.1 THE PARTS OF SPEECH You are probably familiar with terms like noun, verb, preposition, etc. These are what we call parts of speech [Wortarten]. If you look a word up in a dictionary, you will find that its part of speech is given before the meaning. For instance: house, noun: a building for human habitation make, verb: to construct, build, or create, from separate parts We refer here to the following parts of speech: articles, nouns, pronouns, verbs, adverbs, adjectives, prepositions, conjunctions. article An article is a word that comes before a noun, and helps to identify it. English has two articles: the (called the definite article) a or an (before a vowel) (called the indefinite article) noun Words like cat, table, road, etc., are nouns. They may denote concrete objects, like chair, cup, glass; or living things like person, woman, plant, animal; or they may denote abstract “things“ like love, hate, friendship, probability, opportunity, etc. Names like Peter, London, Christianity, Communism are called proper nouns [Eigennamen]. They are spelt with capital letters. pronoun Pronouns are words which stand for nouns which have already been mentioned. They are used to avoid repeating the noun to which the speaker is referring. I, me, you, we, they, them, us, he, him, she, her, it, are called personal pronouns. myself, yourself, himself, etc., are reflexive pronouns. Who?, whom?, which?, whose?, what? are interrogative pronouns. verb Words like run, swim, ride, break, dig, etc., are verbs. Most verbs represent actions or events. But there are many which denote states: be, have, own, seem, etc. adverb These are words like quickly, seriously, sadly, soon, very, etc. Their most typical function is to add information to verbs, telling us where, when, or how an action takes place. But there are others which (like very) can refer to adjectives, to other adverbs, or even to the sentence as a whole, rather than just to the verb. adjective These describe characteristics of nouns and most typically are placed before the noun they describe (the large dog, the red book, etc.) preposition A preposition expresses a relationship between a noun and another part of the sentence. Most of the common prepositions in English refer, when they are used concretely, to relations of space and time: on, off, to, from, under, in, up, down, at, etc. In a simple sentence a preposition must always be followed by a noun. conjunction This is a word which is used mainly to join two sentences in a certain way, like and, but, because, when, although, since, etc. 1.2 GRAMMATICAL FORM We often describe words according to their grammatical form [Flexion]. We say for instance that in the German sentence Ich sah den Mann the noun der Mann is in the “accusative case“ [Wen-Fall], and that the definite article der has the “accusative form“ den. In the same way we say that in the sentence Der Mann hat mir geholfen the personal pronoun ich appears in the “dative case“ [Wem-Fall] mir. In English we speak of the ordinary form (= nominative) and the oblique form (= accusative or dative). The ordinary form of the first person singular pronoun is I. The oblique form is me. It is important to remember that descriptions like “first person singular, oblique form“ are statements about the grammatical form of words. The terms gerund, participle, infinitive, for example, are also statements of grammatical form which apply to verbs. So are terms like past tense, or progressive form. The expressions singular and plural are descriptions of grammatical forms which apply to nouns and pronouns. When we are talking about the grammatical form of a verb, the first thing we have to decide is whether it has a finite or a non-finite form. A finite verb is one which agrees grammatically with its subject. A finite verb always shows tense, and always shows aspect (that is, it appears in either the progressive or the simple form). Examples: I run three miles every day. (first person singular; present tense; simple form) David cooked a meal. (third person singular; past tense, simple form) We have finished our English course. (first person plural; present perfect tense; simple form) You have been playing in the garden. (second person singular or plural; present perfect tense; progressive form) We therefore call the verb forms run, cooked, have finished, and have been playing in the examples above finite verb forms, because they agree grammatically with the subject in each case. A non-finite verb is one which does not agree grammatically with its subject. In fact, most non-finite verbs do not have grammatical subjects anyway. Non-finite verbs often do not show tense or aspect. Examples: Running three miles everyday is very tiring. (No grammatical subject of running is present; running shows no tense or aspect form; running is here a gerund.) To run three miles everyday would be tiring. (No grammatical subject of to run is present; to run shows no tense or aspect form; to run is here an infinitive.) I do not like David cooking meals in my kitchen. (The grammatical subject of cooking, David, is present, but there is no agreement between David and cooking; cooking shows no tense or aspect form; cooking is here a gerund.) David stood in the kitchen, cooking a meal. (The grammatical subject of cooking is David, but there is no subject agreement; cooking shows no tense or aspect form; cooking is here a participle.) We will be talking about gerunds, participles, and infinitives in detail in a later chapter. For the moment it is important simply to recognize why we call these forms non-finite forms. Either they do not appear with a subject; or, when a subject is present, it does not agree with the verb form. What we have been talking about in this section is grammatical structure. Parts of speech like adjectives, nouns, verbs, adverbs, etc., or grammatical forms like gerunds, “third person singular”, present tense, conditional, and so on, all belong to grammatical structure. It is important to distinguish clearly between grammatical structure and what we are going to discuss in the following section: grammatical function [Funktionsbegriffe]. 2. GRAMMATICAL FUNCTION As we saw in the previous section, we can divide a sentence up according to the structures it contains (nouns, adjectives, verbs, etc.). We called these categories parts of speech. A different way of analysing a sentence is in terms of function. That is, we look at the relationships between the different parts of a particular sentence. Functional categories [Satzglieder] are: subject, object, adverbial [adverbiale Bestimmung], complement [Subjektprädikativ/Objektprädikativ], and predicate. As we shall see below, one particular part of speech may fulfil different functions in different sentences. A word like glass, for instance is always a noun; its part of speech, that is, is always the same. But in different sentences the word may function as subject, object, complement, or even as part of an adverbial. Predicate The predicate is the most important part of a sentence. It holds the other parts of a sentence together, and is therefore the centre of the relationship between them. In a sense we can say that the predicate expresses the basic meaning of the sentence [die Satzaussage]. The predicate is always a verb. It may consist - of a single finite verb: David hit Peter. - or of a whole finite phrase including auxiliaries [Hilfsverben]: The book was lying on the table. David has been reading the newspaper. I have done my homework. You can go if you wish. - or it may be a non-finite verb: Walking quickly across the road, … … to see my grandmother on Sunday. (the dots here indicate that these are not complete sentences) Subject The subject of a sentence is most typically that part of it which causes the event named by the predicate [Handlungsträger]. It is that part of the sentence to which the predicate is most intimately related. The information given to us by the predicate tells us first of all about the subject – and then about the subject‘s relationship to the rest of the sentence. In a simple sentence the subject is a noun or a pronoun. If the sentence is declarative (i.e. not a question or command) the subject always comes before the predicate. David hit Peter. The book was lying on the table. We can find out what the subject of a particular sentence is by asking questions like Who verb X? What verb X? (X here simply means the rest of the sentence), for example: Who hit Peter? What was lying on the table? Object There are two kinds of object: the direct object, and the indirect object. The direct object is that part of the sentence which is “acted on“ or directly affected by the subject and the verb. David hit Peter. Peter put the book on the table. In a simple sentence the direct object is a noun or pronoun. We can discover the direct object in a sentence by asking What/whom did the subject verb? Whom did David hit? What did Peter put on the table? The indirect object denotes a person or ”thing” which ”receives” the direct object. In a complete sentence an indirect object cannot appear without a direct object. The indirect object can be paraphrased by a prepositional phrase with to or for. He gave me a watch. = He gave a watch to me. He bought himself a drink. = He bought a drink for himself. The indirect object comes before the direct object in the sentence. The indirect object usually denotes an animate object (that is, a living thing). We will discover the indirect object of a sentence by asking For/to whom did the subject verb direct object? For/to whom did he give a watch? For whom did he buy a drink? Complement A complement denotes an attribute or characteristic of the subject or object. It is something which has to be added to make the sentence complete. Subject complement This is that part of a sentence which follows verbs like be, grow, become, seem, appear, turn; that is, verbs which have no direct object, but need something after them to make the sentence complete. A subject complement [Subjektprädikativ bzw. Prädikatsnomen] describes a characteristic or feature of the subject. David is my brother. Mary seems tired. Sarah became a teacher. Jim turned red. A subject complement can be a noun, pronoun, or adjective. With the verb be we can discover the subject complement by asking Who/What verb subject? Who is that man? What is his occupation? With other verbs we must ask: Who/What did the subject verb? What did Jim turn? What did Mary become? You will notice that this question is similar to the one asked in the case of direct objects. But please remember that subject complements are not direct objects and that verbs like be, grow, and seem do not take direct objects. Object complement This is almost like a second direct object. But unlike a direct object an object complement [Objektprädikativ] can be an adjective as well as a noun or pronoun. The object complement follows the direct object, and describes a characteristic of the direct object which is “caused“ by the verb. Like the subject complement, the object complement is needed by certain verbs to make the sentence complete. He called me a fool. They elected him chairman. The rice pudding made Susan sick. We proved him wrong. The following question will help us to find out what the object complement is: Who/what did the subject verb object? What did he call me? What did the rice pudding make Susan? What did they elect him? Adverbial An adverbial is the part of a sentence which gives us information about how, when, or where something happens. It is in fact like an adverb. An adverb, however, is a part of speech, not a function. The adverbial function can be fulfilled by an adverb; but other parts of speech fulfil adverbial functions too, as you can see below. He went to London. She cooked the dinner slowly. David broke his leg last week. She greeted me in a friendly manner. Tom opened the door with a gasp. As you can see, prepositional phrases, and even noun phrases, as well as ordinary adverbs, can fulfil the adverbial function. Note that all prepositional phrases function as adverbials. In the following chapters we will frequently deal with these grammatical functions. For the sake of brevity we will refer to them by the following abbreviations: S subject Od direct object Oi indirect object Cs subject complement Co object complement P predicate A adverbial 3. THE SENTENCE In the following we are referring only to declarative sentences [Aussagesätze], and not to interrogative sentences [Fragesätze] or commands [Befehlssätze]. These are dealt with later. There are three types of sentence: simple sentences [einfache Sätze], compound sentences [Satzreihen, Satzverbindungen], and complex sentences [Satzgefüge]. 3.1 THE SIMPLE SENTENCE First of all we will ask the question, what is a complete sentence? To be complete a sentence must contain at least a subject and a finite predicate: I subject predicate John whistled. David is swimming. Mary has been cleaning. However, often a subject and a predicate are not enough. The following subjects and predicates do not provide complete sentences: subject predicate Bill hit ? Sarah has broken ? You are hurting ? The question marks in the third column show that something is missing. We must add something to the verbs to get a complete sentence, that is, each of these verbs requires a direct object. For example: II subject predicate direct object Bill hit John. Sarah has broken the teapot. You are hurting me. With verbs like this, then, a direct object is obligatory. Without it the sentence is incomplete. With other verbs, not only a direct object, but also an adverbial is obligatory. The following, for instance, is not a complete sentence: subject predicate direct object David put the book ? We must say where David put the book, othersie the sentence does not make sense. III subject predicate direct object adverbial David put the book on the table. A number of verbs take both a direct and an indirect object: IV subject predicate indirect object direct object He gave me the book. Other verbs require just an adverbial to complete them: V subject predicate adverbial The book is lying on the table. John is in London. Some verbs, as we have seen, need a subject complement to complete them: VI subject predicate subject complement Dorothy is a nurse. The baby seems ill. John has grown fat. Note that the verb be can be completed either with a subject complement, or with an adverbial. Finally, there are a few verbs which need an object complement, as we explained in the previous section: VII subject predicate direct object object complement He called me a liar. The people elected Jones President. A subject and a predicate alone are therefore often not enough to form a complete sentence. What must be added depends on the verb which fulfills the predicate function in any particular case. Let us look again at the different kinds of sentence pattern shown above: I John whistled. subject + predicate II Bill hit John. subject + predicate + direct object III David put his hands in his pockets. subject + predicate + direct object + adverb IV He gave me the book. subject + predicate + indirect object + direct object V John is in London. subject + predicate + adverb VI The baby seems ill. subject + predicate + subject complement VII He called me a liar. subject + predicate + direct object + object complement So in these examples we can see which elements are needed to form complete sentences with certain verbs. All of these sentences have one thing in common: they all contain only one predicate. A sentence containing just one predicate is called a simple sentence. What we have above are the minimum numbers of elements required to make simple sentences with various verbs. We could, of course, add further elements to the sentences: For instance: John sings in the bath. (subject + predicate + adverb) Bill hit John on the nose. (subject + predicate + direct object + adverb John is in London at the moment. (subject + predicate + adverb + adverb) But these sentences still only have one predicate, and are therefore still simple sentences. 3.2 THE COMPOUND SENTENCE We can join simple sentences together by using the conjunctions and, or, but. David drinks Guinness and Marion drinks orange-juice. He likes beer, but he doesn‘t like wine. Or we can have a list of several simple sentences, separated by commas (the last two in this case must be joined by a conjunction). David drinks Guinness, Marion drinks orange-juice, Sarah drinks Bourbon, and George drinks Martini. When we join simple sentences together in this way we get a larger sentence called a compound sentence. The original sentences have become parts of a larger sentence. We call such parts clauses. A clause is a part of a sentence which has its own predicate. A compound sentence consists of two or more clauses which are joined together by conjunctions. The clauses in a compound sentence are called co-ordinate clauses. The conjunctions and, or, but, are called co-ordinating conjunctions. We can therefore say that a compound sentence consists of two or more co-ordinate clauses joined by co-ordinating conjunctions. 3.3 THE COMPLEX SENTENCE The co-ordinate clauses in a compound sentence are independent of each other. They are simply added together. However, we can join clauses so that one becomes dependent on the other. This is done by using conjunctions like although, because, when, etc. Although David likes Marion, Marion does not like David. The clause David likes Marion is dependent on the other clause. It has become a part of that other clause, and cannot stand alone. The conjunction although shows that it must be dependent on some other clause. Sentences like these are called complex sentences. The dependent clause is sometimes called the subordinate clause, and the other clause is called the main clause. The conjunctions used are called subordinating conjunctions. You will find a full list of them in the later section on conjunctions. Here are some more examples of complex sentences: Although Sarah was tired, she did not go to bed. subordinate clause main clause I do not like Barry, because he is always rude to me. main clause subordinate clause We will not go, unless you come with us. main clause subordinate clause When Charlie got home, he did the washing up. subordinate clause main clause A complex sentence consists of one or more main clauses and one or more subordinate clauses. A subordinate clause is joined to a main clause by a subordinating conjunction. 3.4 PHRASES So far we have looked at two kinds of word groups: sentences, and clauses. Now we will deal with a word group which is smaller than the clause: the phrase. (1) the big black dog Each of these words forms a unit. The main word in the unit, the most important word, is dog. We can leave out any of the others. But we cannot leave out dog, for then the unit would be grammatically incomplete. The unit is thus dependent on the noun dog. We call such a unit a noun phrase. (2) red with anger The most important word here is red. It cannot be left out. Red is an adjective, so we call the group in (2) an adjective phrase. There are also adverb phrases, verb phrases, and prepositional phrases, which we will discuss in more detail later. So generally speaking we can say: A phrase is a group of words which belong together. The main word in the phrase is called the head word. Examples: I want to become a good teacher. (noun phrase) Ronald drives his car fast. (noun phrase) The man turned white with fear. (adjective phrase) The book is on the green table. (prepositional phrase) The book is on the green table. (noun phrase) Sarah is sleeping. (verb phrase) Your test was very good. (adjective phrase)