* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download ALWAYS I AM CAESAR

Promagistrate wikipedia , lookup

Food and dining in the Roman Empire wikipedia , lookup

Education in ancient Rome wikipedia , lookup

Cursus honorum wikipedia , lookup

Travel in Classical antiquity wikipedia , lookup

Roman economy wikipedia , lookup

Roman agriculture wikipedia , lookup

Constitutional reforms of Sulla wikipedia , lookup

Early Roman army wikipedia , lookup

Culture of ancient Rome wikipedia , lookup

Roman Republic wikipedia , lookup

Switzerland in the Roman era wikipedia , lookup

Roman army of the late Republic wikipedia , lookup

The Last Legion wikipedia , lookup

Julius Caesar wikipedia , lookup

Roman Republican currency wikipedia , lookup

Roman Republican governors of Gaul wikipedia , lookup

History of the Roman Constitution wikipedia , lookup

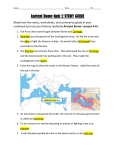

Senatus consultum ultimum wikipedia , lookup

ALWAYS I AM CAESAR W. Jeffrey Tatum Always I am Caesar For Angela Aslanska and Robin Seager ALWAYS I AM CAESAR W. Jeffrey Tatum © 2008 by W. Jeffrey Tatum BLACKWELL PUBLISHING 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK 550 Swanston Street, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia The right of W. Jeffrey Tatum to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks, or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold on the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought. First published 2008 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd 1 2008 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Tatum, W. Jeffrey. Always I am Caesar / W. Jeffrey Tatum. p. cm. Includes bibliographical refrences and index. ISBN 978-1-4051-7525-8 (pbk. : alk. paper) – ISBN 978-1-4051-7526-5 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Caesar, Julius. 2. Rome–History–Republic, 265–30 B.C. 3. Heads of state–Rome–Biography. 4. Generals–Rome–Biography. I. Title. DG261.T38 2008 937′.05092–dc22 2007036296 A catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library. Set in 10.5 on 13pt Minion by SNP Best-set Typesetter Ltd., Hong Kong Printed and bound in Singapore by Markono Print Media Pte Ltd The publisher’s policy is to use permanent paper from mills that operate a sustainable forestry policy, and which has been manufactured from pulp processed using acid-free and elementary chlorine-free practices. Furthermore, the publisher ensures that the text paper and cover board used have met acceptable environmental accreditation standards. For further information on Blackwell Publishing, visit our website at www.blackwellpublishing.com Contents List of Charts, Maps, and Figures Acknowledgements Charts Maps vi viii ix xii Introduction 1 1 Caesar the Politician: Power and the People in Republican Rome 18 2 Conquests and Glories, Triumphs and Spoils: Caesar and the Ideology of Roman Imperialism 42 3 Pontifex Maximus: Caesar and the Manipulation of Civic Religion 61 4 The Stones of Rome: Caesar and the Sociology of Roman Public Building 80 5 My True and Honourable Wife: Cornelia and Pompeia, Calpurnia and Cleopatra 99 6 Great Men and Impersonal Groundswells: The Civil War 122 7 Great Caesar Fell: Philosophy, Politics, and Assassination 145 8 The Evil that Men Do: Caesar and Augustus 167 Important Dates Bibliography Index 189 190 194 v Lists of Charts, Maps, and Figures Charts 1 The family of Julius Caesar 2 Caesar and the Aurelii Cottae 3 Cato and his connections ix x xi Maps 1 The Mediterranean in the time of Caesar 2 The city of Rome during the republic 3 The Roman Forum during the republic xii xiii xiv Figures 1 Colossal portrait head of Caesar, from the 2nd century ad 2 Portrait of Pompey, a first century ad copy of an original dating to the fifties bc 3 Portrait of Cicero, an imperial copy of a late republican original 4 Portrait of Cato in bronze, from the 1st century ad 5 Caesar, a contemporary portrait 6 Funerary procession in a relief from Amiternum, 1st century ad 7 Obverse of a denarius of 44 bc representing Caesar as Pontifex Maximus and as Parens Patriae (Father of his Country) vi 2 7 9 10 19 34 36 lists of charts, maps, and figures 8 Lionel Royer’s Vercingetorix throws his arms at the feet of Caesar 9 Obverse and reverse of a denarius of 32 bc. The obverse depicts Mark Antony, the reverse Cleopatra 10 Portrait of Cleopatra, probably (in large degree) a replica of Cleopatra’s statue in the Temple of Venus Genetrix 11 Cleopatra and Caesarion as Isis and Osiris making sacrifice to the goddess Hathor. South wall of the Temple of Hathor, Dendera, Egypt 12 Reverse of a denarius of 43–42 bc depicting a pileus (a cap indicating freedman status and so an emblem of freedom) between two daggers resting above the phase “Ides of March.” The obverse of this coin depicts Brutus 13 Obverse of a denarius of 44 bc depicting Caesar as Dictator for the Fourth Time 14 Vincenzo Camuccini’s Assassination of Julius Caesar 15 Obverse and reverse of a bronze coin of approximately 38 bc. The obverse depicts Octavian described as “Caesar, son of god.” The reverse depicts Caesar as Divus Iulius 16 Augustus as Pontifex Maximus, a contemporary portrait vii 58 116 118 119 142 150 166 177 179 Acknowledgements It is my pleasure to thank Tricia Smith, at Art Resource, Jenni Adam and Axellle Russo at The British Museum, Luisa Veneziano at the German Archaeological Institute, Rome, and Heidie Philipsen and Claus Grønne at Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek for their helpfulness. I also owe thanks to Indiana University Press for permission to quote from R. Humphries, Ovid. Metamorphoses, and to Penguin Press for permission to quote from D. West, The Aeneid by Virgil. I am grateful to Otago University for appointing me its De Carle Distinguished Lecturer in 2005 and to the university’s Department of Classics for its unexcelled hospitality during my stay. I am indebted to Al Bertrand, Nancy de Grummond, John Marincola, Marjorie and Keith Maslen, and (especially) Jon Hall. My debts to Robin Seager run deeper, and it is my pleasure to acknowledge that reality in the dedication, a billing he shares, for different (but also profound) reasons, with Angela Aslanska. viii CHART 1 THE FAMILY OF JULIUS CAESAR Q. Marcius Rex (pr. 144) Sex. Julius Caesar (cos. 157) L. Julius Caesar (pr. by 129) Sex. Julius Caesar (pr. 123) C. Julius Caesar = Marcia ? Sex. Julius Caesar (cos. 91) JULIA = GAIUS MARIUS CAESAR C. Julius Caesar = Aurelia (pr. ca. 93) Julia = M. Atius Balbus ? = (1) L. Marcius Philippus (2) = (2) Atia (1) = C. Octavius (cos. 56) (pr. 61) CATO = Marcia GAIUS OCTAVIUS/AUGUSTUS Octavia CHART 2 CAESAR AND THE AURELII COTTAE L. Aurelius Cotta (cos. 144) L. Aurelius Cotta (cos. 119) L. Aurelius Cotta (pr. 95) P. Rutilius Rufus (tr. pl. 169) M. Aurelius Cotta = Rutilia C. Livius Drusus (cos. 147) P. Rutilius Rufus = Livia (cos. 105) AURELIA = C. Julius Caesar (pr. c. 92) Mam. Aemilius Lepidus Livianus (cos. 77) JULIUS CAESAR C. Aurelius Cotta (cos. 75) M. Aurelius Cotta (cos. 74) M. Livius Drusus (cos. 112) L. Aurelius Cotta (cos. 65) CHART 3 CATO AND HIS CONNECTIONS Q. Servilius Caepio (cos. 140) Q. Servilius Caepio (cos. 106) M. Livius Drusus (cos. 112) Servilia = Q. Lutatius Catulus (cos. 102) Q. LUTATIUS CATULUS (cos. 78) Q. Servilius Caepio = (1) Livia (2) = M.Porcius Cato (pr. 91) D. Junius = (2) SERVILIA (1) = M. Junius Silanus Brutus (cos. 62) (tr. pl. 83) Mam. Aemilius Lepidus Livianus (cos. 77) Atilia = (1) CATO (2) = Marcia Porcia = DOMITIUS AHENOBARBUS (cos. 54) BRUTUS (2) = (2) Porcia (1) M. CALPURNIUS BIBULUS (cos. 59) Junia Junia Junia =LEPIDUS =P. Servilius =CASSIUS Isauricus (cos. 48) BRITAIN ine Rh Atlantic Ocean GERMANY Dan Alesia TRANSALPINE GAUL CISALPINE GAUL CORSICA Rome IL LY R Black Sea IC UM H BIT Phillipi Munda FURTHER SPAIN SARDINIA PONTUS Zela Pharsalus SICILY M A U R E T A N I A YNIA Mytilene Actium ASIA Utica CILICIA Carthage Thapsus AFRICA MALTA Mediterranean Sea CYPRUS CRETE Alexandria EGYPT Map 1 The Mediterranean in the time of Caesar. Nile 500 km SYRIA NEARER SPAIN Verona PARTHIA Rhône ube 0 3000 feet 0 Porta Collina 800 metres Se rvia nW all Lata Via a M ar cia Anio Vetus r Tibe Aq u 4 3 Saepta 5 Campus Martius Theatre of Pompey (55 BC) Area Sacra di Largo Argentina Porticus Octavia Temples of Apollo and Bellona Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus 6 Temple of Hercules of the Muses House of Temples of Fortuna Aemilius Scaurus and Mater Matuta 1 Forum Temple of Boarium Magna Mater Forum Holitorium Porta Carmentalis and Porta Triumphalis Temple of Hercules Olivarius or Victor Temple of Ceres Ara Maxima Hills of Rome 1 Palatine 2 Capitol 3 Quirinal 4 Viminal 5 Esquiline 6 Oppian 7 Caelian 8 Aventine an Wa ll Circus Flaminius Temple of Concord (121 BC) Forum Temple of Castor (Dioscuri) Se r vi 2 Porticus Metelli Ci rc us M ax im us Appia Aqua 7 Porta Capena Temple of Mercury Tib er s cu rti Po a Ap p ia ilia m Ae ll Wa an Via La tin a Ap pia Horrea Galbana r vi Se a Vi Emporium Vi 8 Tomb of the Scipios Map 2 The city of Rome during the republic. Source: Rosenstein, N., and Morstein-Marx, R. (eds.), A Companion to the Roman Republic (Oxford, 2006). N Argiletum Curia Hostilia / Cornelia Basilica Porcia Fabian Arch (Fornix Fabianus) ilia / /Aem lvia u F ilica Pauli Bas e ova eN erna Tab ra Vi a S ac ica us Dom l Pub Regia Comitium Capitol Carcer Rostra Temple of Vesta Forum Romanum Temple of Concord (121 BC) Lacus Iuturnae Vic r na s Ca p Bas ili e eV pro em ca S nia us Clivu Tabularium (78 BC) e Tab usc us T Temple of Saturn s tere Palatine Hill Temple of Castor itolinu Vicus Iugarius s Area Capitolina Cloaca Maxima (Great Drain) 0 0 100 metres 100 yards Map 3 The Roman Forum during the republic. Source: Rosenstein, N., and Morstein-Marx, R. (eds.), A Companion to the Roman Republic (Oxford, 2006). Introduction “The one debt we owe to history,” as Oscar Wilde insisted, “is to rewrite it.” In the case of Julius Caesar, even if we are not quite prepared to declare ourselves fully paid up, we can hardly be described as falling into arrears. From antiquity to the present day Caesar has remained a favorite subject of biographers, scholarly and amateur alike. And it would be as difficult as it would be remiss to investigate Roman history – or for that matter European history – without at least acknowledging his lasting influence. Caesar abides in all the arts, as a versatile topic and symbol in products of high as well as popular culture, and he remains a potent platform for political discourse about militarism or power or ambitions of an autocratic or hegemonic quality. He is evocative and useful because he is so instantly available to everyone. Even a legend can be stretched too thin, however. Less accessible than Caesar’s reputation is the man himself and the society he both challenged and transformed. Merely to mention Rome, in most circumstances, is to conjure empire – and emperors, of which species Caesar is routinely deemed the author. Hence the familiar transformation of his name into a title: Kaiser and Czar. This is a reality that does not so much enlarge Caesar as it urges his reduction, making him into an uncomplicated figure – the tyrant who gets his way by force of arms, a representation of Caesar that inescapably diminishes his actual merits as a soldier or a general or a politician. It was this very simplification that made possible the purposes to which Caesar was put in the American Revolution, when every patriot was a Brutus striving to free the colonies from the imperial oppression of a British king who could by no stretch of the imagination be likened to Caesar in any but the most tenuous symbolic terms. By then, however, and long before, Caesar had been diluted to Caesarism, which rendered him available to political polemic in nearly any context. This same impulse 1 always i am caesar Figure 1 Colossal portrait head of Caesar, from the 2nd century ad. Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Naples, Italy. Photo: Scala/Art Resource, NY. allowed Caesar to cross the Atlantic, where the opponents of Andrew Jackson could attack Old Hickory as a nineteenth-century Caesar whose personal arrogance, contempt for political restraint and imperialist ambitions threatened the American republic with ruin. In our own century, similar complaints, again invoking the image of Caesar, have been aimed at George W. Bush in publications like the Washington Post, Harper’s Magazine and, in an instance of luscious and timely revenge for King George, the Guardian. Caesar was a man of great capacity and talent, but not a hint of that is operative when Caesar or his reputation is deployed as a term of abuse. Caesar, there can be no missing it, still stands for imperialism and autocracy. And also for personal decadence. Here the evidence is all too abundant, from casinos to toga parties to popular television programming. The historical evidence for Caesar’s sensuality and prodigality and womanizing is not hard to come by. His political rivals emphasized Caesar’s perversities 2 introduction in lip-smacking detail – and the poet Catullus scored multiple successes by lampooning the great general’s disgusting license and licentiousness. This Caesar, however, does not always sit comfortably with his imperial reputation. It is as if the ambitious conqueror of the Gauls and or of the Roman republic seems too busy, too efficient or perhaps too valorous to luxuriate in the company of wanton eastern queens or of immoral young men. Even Cicero once said of Caesar that the man was too dissolute to represent a genuine danger to Rome. Yet this is the same Caesar who was not merely a brilliant military commander but a skillful politician, an eloquent orator, a gifted writer and an inspired reformer. In his own day many saw in Caesar Rome’s final opportunity to eliminate its factionalism, to repair its economy, to give lasting order and stability to its empire – in short, they saw in Caesar a statesman blessed with the talent and the will to usher in the fulfillment of Rome’s true destiny. This was especially the expectation of the masses. After his death, the common people of Rome began to worship Caesar as a god, idolatry that their betters could do nothing to suppress. On the contrary, the idea of Caesar’s divinity caught on and was passed on to his political heirs, becoming one of the essential emblems of the empire and subsisting until Christianity elbowed it out of the way. Christianity hardly spelled the end for the idea of Caesar as something superhuman, however, even if did shunt this article of faith away from the multitude and into the ranks of the elite. Indeed, there has been no shortage of intellectuals for whom Caesar represented nothing less than the perfection of the Roman spirit, the very embodiment of natural superiority, the ultimate Great Man – which are all merely more in the way of simplifications for all their grand and banging formulations. And so we get multiple Caesars: conqueror, autocrat, libertine, god – and Übermensch. Not an easy figure to take in all at once. He is instantly available only in smaller bits. One of the purposes of this book is to examine Caesar’s career by way of a selection of different perspectives, such as his professional rise, his political success, his conquest of Gaul, his relationships with women, his elevation to supreme power and beyond that to the condition of a god. Although I begin at Caesar’s beginnings and I conclude with the state of affairs established by his heir and successor, Augustus, this is neither a biography nor a linear historical narrative. Instead, in each chapter there is an attempt to understand central aspects of Caesar’s life within a pertinent slice of Roman habits, concepts and expectations. There is a reason for this approach. One of the greatest challenges in comprehending Caesar lies in 3 always i am caesar the difficulty of distinguishing the singular qualities of the man from the typical attributes and instincts of his time and class. It is all too easy to regard Caesar as unique, a superman or at the very least a new stage in the evolution of Roman aristocratic politicians, in which case Caesar’s historical role more or less explains itself without any reference to its situation. Caesar triumphed because, being Caesar, what else could he do? It is no improvement on this to let Caesar be subsumed entirely by his context, that is, to regard Caesar as little more than a symptom of all that was characteristic, for good or for ill, of aristocratic Roman society in the first century BC. Matters are more elusive than that, and it is hoped that the following chapters will offer some introduction to the problems of sorting out Caesar’s individuality and the circumstances in which he asserted it with such enduring consequences. Caesar matters in the first instance because he was the agent of a cataclysmic political transformation that forever altered the politics, and the society, of Europe and the Mediterranean. From end of the sixth century bc until Caesar crossed the Rubicon, Rome was a republic. Each year magistrates were elected by the people, and all legislation in Rome was enacted by popular vote. Government relied on the executive capacities of magistrates and on the guidance of the Roman senate, a body composed of all former magistrates. The senate, the magistrates and the people, in their dynamic combination, constituted the Roman republic – and it was this state that dominated Italy and soon thereafter gained mastery of much of the Mediterranean world. And it was this state that Caesar overthrew. Caesar made himself master of Rome and dictator for life. He gathered into his hands all meaningful sources of power and prestige, which he held until he was slain on the Ides of March in 44 bc. It is for this reason that later generations designated him the first of Rome’s emperors, though in actuality that distinction belongs to his heir, Augustus, who, like his predecessor, emerged from another civil war as a permanent autocrat. Augustus, unlike Caesar, was not assassinated, and on the occasion of his death imperial power passed seamlessly to his adopted son, Tiberius. Thereafter Rome was the Roman empire, the durable imprint of which persists in Europe and, by extension, everywhere in the world that has been shaped by a European presence. This shift from republic to empire is one of the very few historical episodes that can fairly be called epoch making, and, although the event was not entirely of Caesar’s doing, it was certainly Caesar who was the essential catalyst of this upheaval, a reality that was understood immediately in Rome. Since that time, Caesar has not dropped from the discourse of political theory or of political polemic. 4 introduction Caesar and Roman Society: A Very Brief Introduction Inasmuch as what follows is not a biography of Caesar, it will be useful to offer here a very concise summation of Caesar’s life and career, if only to give us a framework on which to hang the chapters to come. Specifics and their dates are recapitulated, in tabular form, at the end of this book. I should also explain a few of the more conspicuous peculiarities of Roman culture that will recur in almost every chapter. The most obvious of these is that the Romans employed Latin (and Greek): exhibits of either language are translated whenever they are alien to our own usage (and most are listed in the book’s index along with any other technical terms necessary for describing Roman society). I will not often refer to dates in accordance with Roman practice, the sole exception being the Ides of March, which is simply March fifteenth. More frequently, however, I will discuss money in terms of Roman currency. The Romans in our period, although they employed coins in a variety of weights, tended to rely on the sesterce (sestertius) as their basic unit of reckoning. It is not really possible to convert ancient currency into modern amounts, owing to the deep differences between their economic systems and our own. For our purposes it will perhaps be enough to observe that in Rome an ordinary laborer could be expected to earn three to six sesterces for a day’s effort, on the basis of which income he could only just barely scrape by, that Roman soldiers were paid a salary of 1,200 sesterces each year (of course this does not include their share of the spoils of war and other depredations), that a fortune of 40,000 sesterces sufficed to make one eligible for the First Class in Rome, which comprised Rome’s most prosperous citizens, and that the super rich in Rome were the Knights, whose minimal worth was set at 400,000 sesterces (though many were vastly wealthier than that), and the senators, whose wealth was expected to (and regularly did) exceed a million sesterces. Roman names require some explanation, not simply because their system of nomenclature was different from ours, but also because it was so unimaginative that Romans are easy to confuse (this was true even for the Romans themselves). Every Roman man bore at least two names, his first name (praenomen) and the name of his clan (nomen). The Romans had very few first names, many of which were simply based on numerals, and so this name was infrequently used on its own (when it was so used, it usually indicated a degree of intimacy). Many Romans also had a third name, called a cognomen, some of which were hereditary, others of which 5 always i am caesar were honorific. Unlike the first name, the cognomen was often used on its own to indicate a specific Roman. Naturally, there were various protocols for particular situations. In the case of Caesar, his name was Gaius Julius Caesar. We call him Caesar, as did his contemporaries, but his family were the Julii, the Julians. In practice, Romans are sometimes referred to by their nomen, sometimes by cognomen, sometimes more fulsomely. Some Roman names have been anglicized by custom. Consequently, instead of describing Caesar’s great rival as Gnaeus Pompeius we usually refer to him as Pompey, or as Pompey the Great, inasmuch as he immodestly gave himself the cognomen Magnus (‘the great’). Similarly, Marcus Antonius (who did not have a cognomen) is more familiar in English as Mark Antony. Because Roman families recycled the same names, including first names, so routinely, we sometimes distinguish individual Romans by referring to the highest office they reached in politics (e.g. Sextus Julius Caesar (cos. 157) indicates the man who was consul in 157 bc and not any other Sextus Julius Caesar). This is the practice observed in the genealogical tables that appear in this book. Women in Rome generally had only one name, the clan name in its feminine form: consequently, Caesar’s daughter was named simply Julia. For the sake of ease and clarity, in the index to this book all Romans are listed both by nomen and by their more familiar designation (if they have one): for instance, Marcus Porcius Cato can be found under the heading Cato as well as under Porcius. Let me turn now to a very rapid and entirely basic run through Caesar’s life. Caesar was born in 100 bc to an ancient patrician family. Romans were unevenly divided between plebeians (the bulk of all Romans) and patricians. In early Rome, the patricians had been a privileged caste. By the late republic, however, although patrician status carried a degree of social cachet, not least because by then there were fewer than twenty patrician families who subsisted, it carried nothing like its original importance. More important, as we shall see, was nobility, descent (and especially recent descent) from a forebear who had won the consulship, Rome’s highest magistracy. This was a category that included plebeians, and it outshone patrician rank. Caesar’s family had in any case not distinguished itself in recent generations. Never the less, as we shall see in the first chapter, Caesar enjoyed important family connections, and they helped to see him through the first great crisis of his life, the civil war between Gaius Marius and Lucius Cornelius Sulla. Marius, who was Caesar’s uncle, was a great military hero. He had triumphed after his victory in North Africa and, far more important, he had saved Italy from invasion by powerful Germanic tribes, in recognition of 6