* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Two-electrode non-differential biopotential amplifier

Flip-flop (electronics) wikipedia , lookup

Flexible electronics wikipedia , lookup

Ground (electricity) wikipedia , lookup

Electrical substation wikipedia , lookup

Electronic engineering wikipedia , lookup

Stray voltage wikipedia , lookup

Ground loop (electricity) wikipedia , lookup

Scattering parameters wikipedia , lookup

Mains electricity wikipedia , lookup

Alternating current wikipedia , lookup

Electromagnetic compatibility wikipedia , lookup

Current source wikipedia , lookup

Immunity-aware programming wikipedia , lookup

Buck converter wikipedia , lookup

Audio power wikipedia , lookup

Oscilloscope history wikipedia , lookup

Earthing system wikipedia , lookup

Switched-mode power supply wikipedia , lookup

Negative feedback wikipedia , lookup

Public address system wikipedia , lookup

Zobel network wikipedia , lookup

Resistive opto-isolator wikipedia , lookup

Schmitt trigger wikipedia , lookup

Wien bridge oscillator wikipedia , lookup

Two-port network wikipedia , lookup

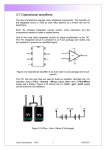

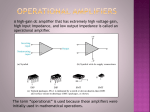

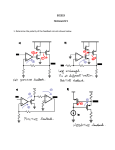

Two-electrode non-differential biopotential amplifier D. Dobrev Centre of Biomedical Engineering, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Sofia, Bulgaria Abstract—A circuit is proposed for a non-differential two-electrode biopotential amplifier, with a current source and a transimpedance amplifier as a potential equaliser for its inputs, fully emulating a differential amplifier. The principle of operation is that the current in the input of the transimpedance amplifier is sensed and made to flow with the same value in the other input. The circuit has a simple structure and uses a small number of components. The current source maintains balanced common-mode interference currents, thus ensuring high signal input impedance. In addition, these currents can be tolerated up to more than 10 mA per input, at a supply voltage of 5 V. A two-electrode differential amplifier with 2610 MO input resistances to the reference point allows less than 0.5 mA per input. The circuit can be useful in cases of biosignal acquisition by portable instruments, using low supply voltages, from subjects in areas of high electromagnetic fields. Examples include biosignal recordings in electric power stations and electrically powered locomotives, where traditionally designed input amplifier stages can be saturated. Keywords—Bio-electric amplifier, Non-differential circuit, Electromagnetic interference Med. Biol. Eng. Comput., 2002, 40, 546–549 1 Introduction 2 Amplifier circuit THE USE of conventional unsymmetrical amplifier circuits in biomedical engineering is very limited, owing to their inadequacy in suppressing interference from the power-line. One of the patient electrodes being the common reference point of the amplifier, the interference current flows to this point through the respective electrode impedance. The voltage drop on this electrode impedance is amplified and leads to circuit saturation or to masking of the bio-electric signal. Many applications connected with biosignal acquisition could benefit from the use of only two electrodes. Electrocardiogram monitoring in intensive care wards, ambulatory monitors, defibrillators etc. are among the most common examples. Recently, a circuit of a two-electrode differential amplifier was developed, using controlled current sources at its inputs. Its main feature was a drastic reduction in common-mode input voltage (DOBREV and DASKALOV, 2002). An amplifier circuit is presented here, whose performances are quasi-equivalent to the ones of the above-cited differential amplifier. It is of a much simpler and more economical structure. These two circuits, using current sources at their inputs, are unable to compensate for electrode imbalance, resulting in transformation of part of the common-mode voltage to differential signal. However, this is a drawback to all types of biosignal amplifier, unless very special, but complicated and not quite efficient, measures are taken (see, for example, BREDEMANN and SEITZ (1990) and YONCE (2000)). An equivalent circuit of the body–amplifier interface is presented in Fig. 1. Part of the interference current flows through the power-line–body stray capacitance Cp the body impedance Rbd (presented as resistance for simplification) and the stray capacitance to ground Cb . The skin–electrode impedances are Zea and Zeb , (incorporating Rea , Cea and Reb , Ceb , respectively), and Cg is the capacitance between the reference point and ground. Another part of the interference current ðIa þ Ib Þ traverses the impedances Zea and Zeb and Cg to ground. The interference current Ib is converted to voltage V1 at the output of operational amplifier A1 , which drives the potential of input b to the common point. On the other hand, V1 is used to control the current source, connected to amplifier input a. It can be seen that Ib Zf b ¼ V1 ; V1 gm ¼ Ia , where gm is the transconductance of the current source. The circuit is quasi-symmetric with respect to the interference currents, if Correspondence should be addressed to Dr Dobromir Dobrev; email: [email protected] Paper received 19 February 2002 and in final form 24 June 2002 MBEC online number: 20023711 # IFMBE: 2002 546 gm ¼ I=Zf b Assuming Zea ¼ Zeb , the voltage drops on them will cancel, thus cancelling the interference. However, Zea and Zeb are not equal, and the interference current multiplied by their difference will result in an unwanted input signal to A2 . As commented above in Section 1, this is a drawback of most biosignal amplifiers. Operational amplifier A1 maintains the potential of input b equal to the reference point (virtual ground), and thus A2 amplifies the voltage from inputs a and b. As one of the electrodes is directly connected to the inverting input of A1 , any capacitance inserted at the input would thus introduce a phase shift. Thus a potential instability can arise, which is typical for any potential equalisation circuit involving connection to the subject’s body with its unknown impedances. Medical & Biological Engineering & Computing 2002, Vol. 40 Cp 4p Is 10n Ia 2k + – Rbd 100 Vpl + a Zea A2 Ib Zeb Zfb b 2k Cb 150p out – – 10n Cg + V1 A1 40p Fig. 1 Equivalent circuit of patient–amplifier interface. Impedances Zea and Zeb include Rea , Cea and Reb , Ceb respectively The closed-loop transfer function Acl for the circuit of Fig. 2a, assuming the operational amplifier A1 as ideal is The problem of ensuring stability has been considered by LEVKOV (1988), for three-electrode amplification. In the case of a two-electrode amplifier, an appropriate selection of the feedback impedance Zf b is to be considered. The equivalent circuit of the current-to-voltage converter is shown in Fig. 2a. The interference current is represented by the current source Ipl , and its output impedance is represented by Co , with Co being the equivalent of the series connection of Cg , Cb þ Cp and Ceb , which is the capacitance component of Zeb . Practically, Co Cg for non-screened patient leads. Acl ¼ 1 þ sðCf b þ Co Þ Rf b 1 þ s Cf b Rf b with a zero for wz ¼ 1=ðRf b ðCf b þ Co ÞÞ and a pole for wp ¼ 1=ðRf b Cf b Þ. Cfb 33p Rfb 300k – – + Co 40p Ipl + A1 a 160 Cfb=0 Az Ω, dB 120 dB + + + + + + Acl, dB 80 + Cfb=33pF Cfb=0 40 + Aol, dB 0 –20 Cfb=33pF 10–2 10–1 100 101 102 103 104 105 106 Hz b Fig. 2 Potential-equaliser amplifier: (a) equivalent circuit; ( b) gain-frequency characteristics by simulation. Vertical scale is in dB. ‘I-V gain’ is current-to-voltage transverter gain (O) (or transimpedance); Aol and Acl are open-loop and closed-loop gain, respectively, with and without feedback capacitor Cf b . Medical & Biological Engineering & Computing 2002, Vol. 40 547 The transimpedance transfer function Az (again assuming A1 as ideal) is Az ¼ are precisely matched. The output impedance Zo depends on the common-mode rejection ratio (CMRR) of U1 Rf b 1 þ s Rf b Cf b Zo ¼ Rgm 10CMRR=20 where CMRR is expressed in dB. For example, the CMRR of INA105=BB is 80 dB, yielding a very high value of Zo . The operational amplifier U2 was selected for a low input bias current (MOSFET or JFET input stage) and a high open-loop gain, to minimise the input error voltage. In this case, the popular TL072 is used. The amplifier inputs InP and InN can tolerate serial resistors, for protection and=or as part of a low-pass filter. The voltage drops across such resistors will cancel and not be amplified by U3. Additionally, the circuit stability is increased. An example of the amplifier performance is demonstrated in Fig. 4. The circuit is supplied by two 9 V batteries and connected with non-screened wires to a pair of chest electrodes located about both axillae of a subject under test, who was positioned about 50 cm from a power-line cable collector. A batterypowered oscilloscope was connected to the output of U3B. With Rgm disconnected (Fig. 4a), the acquired signal was extremely noisy. Restoring the circuit by reconnecting Rgm allowed recording of an electrocardiogram that was virtually free of interference. The circuit was also tested with a power line-powered oscilloscope. Under the above-described conditions, the result for the proposed circuit was as follows: measured commonmode currents of 0.8 mA per input, leaving a large reserve up to saturation. With a differential amplifier, having 2610 MO input resistances to reference point and CMRR ¼ 80 dB, full saturation was obtained. It needed 12 V supply voltage to start operating slightly below saturation. The residual 50 Hz interference level in these conditions did not differ for the two types of amplifier and was about 1 mV referred to the input. This result can be compared with that of a previous test under the same conditions, again using a differential amplifier, with 10 MO resistors between each input and the floating reference point as a reference circuit (see Fig. 7a of DOBREV and DASKALOV (2002)). The advantage of the proposed circuit is its power to tolerate common-mode currents of about 10 mA and also has a pole for wp Taking into account now that the operational amplifier is not ideal, especially with respect to the frequency dependence of the open-loop gain Aol , we obtain Az ðsÞ ¼ Rf b Aol 1 þ sCf b Rf b 1 þ sCo Zf b þ Aol When we evaluate the circuit stability by the loop gain, if Cf b ¼ 0, the phase margin is 1.73 , and oscillations will appear. With Cf b ¼ 33 pF, the phase margin becomes 75 , meaning stable functioning. The circuit of Fig. 2a was simulated using OrCAD 9.2 PSPICE. The results are shown in Fig. 2b, for Cf b ¼ 0 and Cf b ¼ 33 pF. The A1 open-loop and closed-loop gains are shown, together with the transimpedance gain (‘I–V gain’, or current-to-voltage converter gain), as a function of frequency. It can be seen that, for Cf b ¼ 0, there is a peak of Acl and Az , showing that the circuit would oscillate about the corresponding frequency. With Cf b ¼ 33 pF, there are no peaks in the Acl and Az characteristics, and the circuit will be stable. However, a higher value for Cf b is not recommended. It can be seen from Az that this would reduce the frequency band of the currentto-voltage converter and thus increase the phase shift between Ia and Ib . 3 Practical amplifier circuit The circuit of an amplifier built according to the proposed principle is shown in Fig. 3. The current source U1 is of the most common type and can be built around an available operational amplifier. Using an integrated circuit INA105=BB, AMP03=AD, or similar type, can be very practical, as the resistors U1 INA105 or similar Vcc 25k 25k – 25k 25k + Rgm 300k InP Vcc + – Vee U2A TL072 Vee 24k Cfb 33p InN – + Rfb 300k U2B TL072 Vcc + – 15n Vee U3A TL072 24k 2u + out 15n 1.5M 1k U3B TL072 – 39k 10n 1k Fig. 3 Practical amplifier circuit 548 Medical & Biological Engineering & Computing 2002, Vol. 40 1V per division 200 ms per division a 1V per division The high value of the resistor between the amplifier input and the current source keeps possible auxiliary patient current below the safety standard limits. The circuit can accept high-value input filter resistances, which can also be a security measure against possible fault conditions. This amplifier cannot prevent the transformation of commonmode interference voltage into unwanted differential signal owing to skin–electrode imbalance. As is well known, this type of transformation is typical for biosignal amplifiers, and its prevention involves complicated circuits, whose performances usually do not merit the investment of material and effort for their implementation. On the other hand, modern software methods for power-line interference suppression and even elimination are very efficient (DASKALOV et al., 1998), provided the pre-amplifier does not become even momentarily saturated (for example, during interference or baseline drift plus peak amplitudes of the signal). In this sense, it should be remembered that modern battery-equipped instruments, such as Holter-type recorders and automated external defibrillators, tend to use relatively low supply voltages, for example from 3 V to no more than 5 V, which makes them more sensitive to saturation. This point suggests that avoiding or reducing the possibility for saturation, preferably at the amplifier input, becomes an important issue when obtaining biosignals in conditions of strong electromagnetic fields. Examples might be Holter-type recordings from drivers of powerful electric machines, electric power station operators etc. Especially sensitive cases could be ones where defibrillators are to be used in such locations. References 200 ms per division b Fig. 4 Electrocardiogram and interference acquired from subject near power-line cable collector: (a) with conventional nondifferential amplifier; (b) with proposed circuit per input, at a supply voltage of 5 V. With the 2610 MO amplifier, only 0.5 mA per input could be tolerated. BREDEMANN, M., and SEITZ, F. (1990): ‘Differential amplifier’. Patent Number EP0380976 DASKALOV, I. K., DOTSINSKY, I. A., and CHRISTOV, I. I. (1998): ‘Developments in ECG acquisition, preprocessing, parameter measurement and recording’, IEEE Eng. Med. Biol., 17, pp. 50–58 DOBREV, D., and DASKALOV, I. (2002): ‘Two-electrode biopotential amplifier with current-driven inputs’, Med. Biol. Eng. Comput., 40, pp. 122–127 LEVKOV, Ch. (1988): ‘Amplification of biosignals by body potential driving. Analysis of the circuit performance’, Med. Biol. Eng. Comput., 26, pp. 389–396 YONCE, D. (2000): ‘Input impedance balancing for ECG sensing’. Patent Number WO00=45699 4 Discussion and conclusions Author’s biography Combining a conventional non-differential amplifier with a current source driven by the common-mode interference signal and with a potential-equalising circuit, a biosignal amplifier was built with added protection against saturation. It uses three integrated circuits and a small number of passive components. Its performance matches that of a differential amplifier, but with added tolerance of high common-mode input currents. It is convenient for use in biosignal acquisition instrumentation to be operated in a high electromagnetic interference environment and where the number of electrodes may be a critical factor. DOBROMIR DOBREV obtained his MSc in Electronic Engineering from the Technical University of Sofia, in 1994. He specialised in medical electronics, with a diploma thesis on filtering and amplification of biosignals. He has worked in the Institute of Medical Engineering of the Medical Academy as a Research Assistant and, since 1997, has been with the Centre of Biomedical Engineering of the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences. His recently obtained PhD is in the field of neonatal monitoring. The study of analogue circuits, including the design and integration of biosignal amplifiers and filters, electrical impedance measurement circuits and transient processes in amplifiers, are among his present research interests. Medical & Biological Engineering & Computing 2002, Vol. 40 549