* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download File - International Nursing Symposium

Traveler's diarrhea wikipedia , lookup

Neglected tropical diseases wikipedia , lookup

Meningococcal disease wikipedia , lookup

Hepatitis C wikipedia , lookup

Gastroenteritis wikipedia , lookup

Human cytomegalovirus wikipedia , lookup

Trichinosis wikipedia , lookup

Orthohantavirus wikipedia , lookup

Whooping cough wikipedia , lookup

West Nile fever wikipedia , lookup

Middle East respiratory syndrome wikipedia , lookup

Yellow fever wikipedia , lookup

African trypanosomiasis wikipedia , lookup

Onchocerciasis wikipedia , lookup

Hospital-acquired infection wikipedia , lookup

Hepatitis B wikipedia , lookup

Oesophagostomum wikipedia , lookup

Neonatal infection wikipedia , lookup

Visceral leishmaniasis wikipedia , lookup

Marburg virus disease wikipedia , lookup

Typhoid fever wikipedia , lookup

Neisseria meningitidis wikipedia , lookup

Yellow fever in Buenos Aires wikipedia , lookup

Leptospirosis wikipedia , lookup

Schistosomiasis wikipedia , lookup

Coccidioidomycosis wikipedia , lookup

Rocky Mountain spotted fever wikipedia , lookup

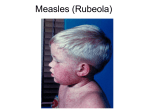

Donald McLaren, MD Seventh International Symposium in Continuing Nursing Education/March 2014 Goals of talk To highlight measles as a still very important major cause of under 5 mortality in the developing world and discuss diagnosis, complications and treatment To discuss clinical features, diagnosis, complications and treatment of various childhood exanthems To point out some other childhood diseases which may present with a rash which you should not miss because they are potentially fatal if not treated early Definitions Exanthem – widespread rash – from Greek “a breaking out.” A generalized cutaneous eruption associated with a systemic illness Morbilliform rash – rash that looks like measles. Macule – discolored area on skin not raised above the service Papule – raised solid lesion on skin without visible fluid – varies in size but < 5mm Vesicle – small elevation of epidermis containing serous fluid < 5 mm Petechiae – very small red spot on skin due to hemorrhage – does not blanch to pressure Childhood exanthems initially named by number from first to sixth in 1905 - measles, scarlet fever, rubella, 4th never existed, erythema infectiosum, and roseola infantum. Many other causes of exanthems in children. Measles (Rubeola) Prior to vaccine 90% acquired measles by 15 yoa With high rates of immunization, age in epidemics in U.S shifted downwards to 6 months of age Still major cause of mortality in developing world. In 2000, 31-39.9 million got measles with 733,000 – 777,000 deaths (5th in < 5 mortality) By 2011 mortality dropped by 71% (WHO) 1990-2008 decreased from 7% to 1% of < 5 mortality! Van dan Ent M.M.V.X., Brown, DW, Hoekstra, J, Christie A, Cochi SL. Measles Mortality Reduction Contributes Substantially to Reduction of All Cause Mortality Among Children Less than Five Years of Age, 1990-2008. JID 2011:204 (Supplement 1) Epidemiology 1990-2008 decreased from 7% to 1% of < 5 mortality! Van dan Ent M.M.V.X., Brown, DW, Hoekstra, J, Christie A, Cochi SL. Measles Mortality Reduction Contributes Substantially to Reduction of All Cause Mortality Among Children Less than Five Years of Age, 1990-2008. JID 2011:204 (Supplement 1) Goal of 95% reduction over 2000 by 2015 and elimination in 5 WHO regions by 2020 Africa – 2001-8 vaccination rate 57-73% SE Asia – 2000-2008 46% reduction in measles deaths > 70% decreased mortality 2000-2007. 197,000 in 2007 85% measles mortality now in Africa, SE Asia Measles epidemiology Highly contagious – 75% attack rate if exposed U.S. pre-vaccine: 500,000-4,000,000 cases/year; 48,000 hospitalized; 1000 chronically disabled; 500 deaths – No longer endemic. 2001-2011 63 cases/year reported – most 220. 88% import (travel) related and 66-85% of unvaccinated or unknown status. Outbreak = 3 or more cases linked in time and place Incidence of global measles 2004 http://dualibra.com/wpcontent/uploads/2012/04/037800~1/Part%207.%20Infectious%20Diseases/Section%2015.%20Infections%20Due%20to%20RNA%20 Viruses/185.htm http://www.who.int/immunization/monitoring_surveillance/burden/vpd/surveillance_t ype/active/big_measlesreportedcases6months_PDF.pdf http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Measles Hunter’s Tropical Medicine and Emerging Infectious Diseases http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Measles Clinical Manifestations of Classic measles Incubation period: asymptomatic 8-10(6-19) days Prodrome: Fever, malaise, anorexia Followed by the 3 Cs. Conjunctivitis, coryza, cough – photophobia. 2-3 days. Fever as high as 400 Koplick spots (pathognomonic) often appear 48 hours before rash. 1-2 mm whitish or gray elevations on erythematous base in buccal mucosa and other parts of mouth like “grains of salt on a red background” http://www.atsu.edu/faculty/chamberlain/Rubeola.htm Exanthem: Maculopapular blanching rash Starts on face then moves downward and outward Often become confluent. Usually spares palms/soles - Occasionally petechial Lymphadenopathy, high fever, respiratory signs, pharyngitis, nonpurulent conjunctivitis. Improvement within 48 hours with rash disappearing in same order as appearance Darkens to brown color after 3-4 days and fades followed by fine desquamation. Lasts 7 days. Recovery, immunity. Cough up to 2 weeks. Fever beyond day 4 of rash means complication Immunity lifelong and reinfection rare. Contagious 5 days pre-rash to 4 days after rash appears Anergy not uncommon for several weeks after measles (meaning PPD unreliable) Measles rash Measles rash Measles Clinical Course Hunter’s Tropical Medicine and Emerging Infections Diseases Other forms of measles Modified: Pt. with incompletely protective measles antibody. Similar but milder symptoms, longer 17-21 day incubation period Atypical: Rare - those immunized with killed virus vaccine used 1963-67. Can be very severe with respiratory distress or mild Starts with HA, high fever 7-14 days post exposure Dry cough, pleuretic chest pain, pulmonary/hilar nodular lymphadenopathy M-P rash 2-3 days later begins on extremities, spreads to trunk Involves palms, soles and spares upper chest, neck and head May be purpuric, urticarial, hemorrhagic, accentuated in skin folds Diagnosis In context of endemic measles fairly easy with clinical presentation DDx – many other rashes, but symptoms and progression of rash should usually distinguish Where there is low measles prevalence should diagnose with paired acute/convalescent sera for antimeasles IgM and IgG - at least fourfold increase in IgG. IgM present within 3, gone by 30 days post rash IgG 7 days post rash – peak in 14 days after rash. Complications Higher in developing countries: 4-10% More common in very young and old (< 5; > 20) More complications with malnutrition, crowding, low vitamin A, immunocompromised, pregnancy Deaths due to pulmonary (pneumonia and croup) or CNS complications Morbidities include blindness, malnutrition Pulmonary complications Pneumonia, bronchiolitis, LTB (croup), OM Measles giant cell pneumonia in those who are immunocompromised 5% get bacterial super-infection most commonly from Staph, Strep, H. flu, or pneumococcus and in one South African study 85% deaths due to viral or bacterial lung infection Antibiotic prophylaxis MAY decrease incidence of secondary infection. Needs more study. Neurologic complications Encephalitis 1 / 1000 cases within days of rash. Most recover but 25% neurodevelopmental sequela; 15% rapidly progressive fatal Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) Demyelinating disease during recovery phase Autoimmune response within 2 wks of infection or vaccine (F, stiff neck, HA, seizures, mental status changes, paralysis) 10-20% mortality (frequent residual neurological abnormalities) SSPE (Subacute Sclerosing Panencephalitis) Fatal progressive degenerative CNS disease 7-10 years post infection Increased if measles before age 2 years. Risk much less with vaccine < 1/12 (1:1,000,000) Other complications Eye: measles induced keratitis, vitamin A deficiency, corneal ulceration, 20 herpes simplex or bacterial infection, herbal remedies in eye can lead to blindness • GI: Gingivostomatitis, gastroenteritis, D, hepatitis Diarrhea, stomatitis often lead to worsening nutritional status Marasmus or Kwashiokor • Cardiac (myocarditis and pericarditis) • Immune suppression (T cell infection) • During pregnancy – uncommon – NOT a teratogen. May have more severe course. Also increased spontaneous abortion and perinatal mortality. Treatment Antipyretics Fluids Tx bacterial super-infection, complications Vitamin A – WHO vs. U.S. recommendation Especially in young < 2 yoa, complicated measles Mortality, complications, hospital stay reduced. One study showed no OVERALL decreased mortality but decreased mortality if under age 2 Role of vitamin A WHO – 2 doses vitamin A to all children with measles in communities with recognized vitamin A deficiency problem and measles related mortality is > 1%. Must give within 5 days of rash onset to reduce morbidity and mortality Why does this reduce mortality? Most likely damage to epithelial membranes increased with low vitamin A AND Depression of immune response with low vitamin A Vitamin A continued AAP and vitamin A Age 6 months to 12 years AND hospitalized OR > 6 mo with immunodeficiency, ophthalmological evidence of vitamin A deficiency, impaired intestinal absorption, significant malnutrition, immigration recently from area with high measles mortality. Single dose (6-12 mo 100,000; > 12 mo 200,000 IU) Repeat day 2 and 28 if evidence vitamin A deficiency http://www.measlesrubellainitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/Treating-Measles-in-Children1.pdf http://www.measlesrubellainitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/TreatingMeasles-in-Children1.pdf Prevention Vaccine beginning at 12 months of age As early as 6 months if travelling to endemic area But must give 2 doses after age 1 Many foreign countries give at 9 months MMR vs. MMRV (Slightly greater risk of seizure with MMRV with first dose only) Very effective – 95% if 1st vaccine at age 12 moa Second dose at least 28 days later (ACIP) and for sure by school entry at 4-6 years of age Prevention if exposed Measles vaccine within 3 days of exposure Immune globulin if can’t get vaccine, or 3-6 days after exposure, or < 12 months old in household SE vaccine: Fever (5-15%) or transient rash (5%) 1-2 weeks later; NO autism association If refuse vaccine – exclude from setting for 3 weeks after onset of rash of last measles case Scarlet Fever or Scarlatina Diffuse erythematous eruption usually associated with strep pharyngitis and following it by 12-48 hours Due to delayed – type skin reactivity to pyogenic exotoxin from Group A (B and C) streptococci Rash: diffuse blanching erythema Numerous small 1-2 mm papular elevations giving rise to sandpaper feel to skin Starts head/neck with circumoral pallor , strawberry tongue Extends to trunk then extremities Ultimately desquamates. Most marked at skin folds of inguinal, axillary, antecubital and abdominal areas, pressure points. Pastia’s lines – petechia in antecubital fossa and axillary folds. Treatment – antibiotics: Penicillin, Amoxicillin or Ampicillin, erythromycin, cephalosporins Isolate till 24 hours after antibiotics started Rubella (“German Measles”) Three day measles. Initially thought to be measles or scarlet fever variant. Described 1750s in Germany Named rubella in 1866 Interest increased when Australian eye doctor described teratogenic effects on the eye in 1941 Prior to good vaccine up to 12 million cases in 1964-65 with 20,000 CRS (Congenital rubella syndrome) cases Pre-vaccine (1969) 58 cases/100,000. 1983 ↓ to 0.5 / 100,000. Eliminated from U.S. (2004); Americas (2010) Clinical Course of Rubella Incubation 14-18 days (12-23) after inhalation of particulate aerosols Contagious 1-2 wks before clinical recognition Viral shedding decreases with appearance of rash but contagious till a week after rash Re-infection possible but rarely leads to CRS “Rubella is a mild disease with clinical features that are neither distinctive nor diagnostic.” Hartley AH and Rasmussen JE. “Infections Exanthems.” Pediatrics in Review accessed online a http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/content/9/10/321 Signs/symptoms Usually mild and often asymptomatic Acute onset M-P rash - few systemic symptoms Rash erythematous, nonpruritic, discrete Low grade fever, lymphadenopathy concurrently or 1-5 days prior to rash Lymphadenopathy – posterior cervical, posterior auricular, suboccipital Spreads face to trunk, extremities – fading on face by day 2 Generalized within 24 hours, gone within 3 days (1-8) without peeling or scaling. Much more rapid than measles; does not darken or coalesce Teens, adults – more likely to be more symptomatic with fever, systemic complaints. Arthralgias, arthritis in 70% lasting up to a month – knees, wrists, fingers Complications more common in adults – postinfectious encephalitis (1 in 6000 within week): immune mediated and good prognosis OR progressive rubella panencephalitis (rare and devastating) Congenital Rubella Syndrome Real concern with Rubella is CRS – hearing loss, MR, CV defects, ocular defects CRS highly variable but any organ system can be effected. Can manifest throughout life. Vaccine effective; goal of immunization to prevent CRS (25% transient arthralgia; 10% arthritis after vaccine) Rubella still a big deal in third world Congenital rubella syndrome Highest risk first 10 weeks of gestation – Unlikely if after 18-20 weeks. 80% risk first trimester Consider in any birth if rubella during pregnancy or any infant with IGR or other findings c/w CRS Children can shed virus after CRS at least a year Dx of rubella unnecessary except when CRS suspected. Cord blood IgM or persistence of IgG beyond 1st year of life (normally disappears at 3-6 weeks) Erythema Infectiosum or Fifth disease Mild febrile disease with rash: caused by Parvovirus B19 infection Five forms of B19 infections which also causes Arthropathy Non-immune hydrops fetalis with Intrauterine fetal death or miscarriage Transient aplastic crisis in chronic hemolytic disorders Chronic pure RBC aplasia in the immunocompromised Signs/symptoms Incubation period 4-14 days – biphasic illness 25% asymptomatic, 50% flu like symptoms, 25% classic presentation including rash. First week viremia with non-specific flu like illness (fever, malaise, myalgia, coryza, HA, pruritis) Can have low platelets, Hgb, or leukopenia Next week rash and/or arthralgia In adults less characteristic - can be confused with rubella Fifth disease outbreaks among school age children Nonspecific prodromal symptoms (Fever, coryza, HA, N, D) 2-5 days later classic erythematous malar rash (slapped cheek appearance)relative circumoral pallor Followed by reticulated (lacelike) rash on trunk, extremities Viremia has resolved and child feels well by time rash appears (rash felt to be immune mediated) Typical feature is recrudescence of rash to nonspecific stimuli (i.e. Δ Temp, sunlight exposure, exercise, emotional stress) resolving within weeksmonths or rarely years. Can also be associated with morbilliform rash, confluent or even vesicular rash No treatment If normal immune system – not contagious after rash no need to isolate Infectious – close contact, large droplets, blood transfusion Household transmission in 50% Risk of fetal death with maternal infection 2-5 % Rarely if ever causes congenital anomalies If get when pregnant – weekly US. May need Hct via umbilical vein and transfusions and other treatment and intrauterine treatment of pleural effusion, ascites Roseola Infantum Exanthem subitum, pseudorubella, sixth disease Caused most often by herpes virus 6 (HHV-6) 2/3 have a + serology to HHV-6 by age 1 year Viremia precedes rash; antibody forms at time of rash. Peak incidence 7-13 months. 90% occur at < 2 years Occurs year round Incubation 9-10 days. Virus believed to be shed for life. Clinical presentation 3-5 days fever often over 400 which resolves abruptly with appearance of the rash (or within 24 hours) Irritability – otherwise active, alert, appears well Other symptoms Bulging fontanelle often leads to LP Lymphadenopathy 98% erythematous TMs 93% irritability 92% Nagayama spots (uvulopalatoglossal junctional macules or ulcers, papules, purpuric rash) 87% Anorexia 80%, URTI 25%, D 15%, cough 11%, convulsions 4% As fever goes away, blanching M, MP, occasionally vesicular nonpruritic rash starting on neck, trunk and spreading to face and extremities. Persists 1-2 days and often confused with drug allergy Lab: Relative neutropenia; Low platelets; mild atypical lymphocytosis. (nadir 3000 day 3-6) Usually benign and self limited. Seizures 0-6% of time, aseptic meningitis, encephalitis and TTP. NO recommendation for exclusion from child care. Sporadic cases not contagious. Contagious prior to rash and can return to school once fever gone. Can be fatal in immunocompromised http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/medical/IM03111 Chicken Pox - Epidemiology Pre-1995 CDC estimated about 4,000,000 cases; 11,000 admissions; 100 deaths / year Since vaccine – fewer cases, complications, admissions, deaths Prior to vaccine >95% immune by age 20 and only 2% of adults susceptible More serious with increasing age (and < 1 yo). In past adults > 20 represented 5% of cases but 55% of deaths. In U.S. > 92% vaccinated - 90% decreased incidence Powerful herd immunity effect as rate has gone down in unvaccinated adults. Second dose vaccine recommended since 2006 Secondary attack rate in family > 90% in susceptible individuals By contact with aerosolized NP secretions or direct contact with vesicle fluid from skin lesion Clinical presentation Incubation 14-16 days (10-21) Prodrome: fever, malaise, pharyngitis, loss of appetite Generalized pruritic vesicular rash within 24 hours - successive crops of rash over several days Macules-papules–vesicles - pustular -- crusted papules. Lesions in different varying stages on face, trunk, extremities is hallmark of disease Clinical New lesions stop developing within 4 days Most fully crusted in normal host within 6 days Crusts fall off within 1-2 weeks leaving area of hypopigmentation temporarily Infective 48 hours prior to rash till all skin lesions crusted Can be reinfected but unusual 20% with one vaccine develop Chicken Pox if exposed (breakthrough disease) Milder and atypical – fewer lesions and less fever if one gets varicella after one dose vaccine Fewer complications Complications Those at increased risk – adults, very young, pregnant women, immunocompromised Complications – not a benign disease GAS soft tissue infection, cellulitis, myositis, fasciitis, toxic shock Encephalitis, Reyes, transverse myelitis, etc. Acute cerebellar ataxia (complete recovery) Pneumonia – major cause M/M in adults – not common since vaccine – treat with acyclovir as high mortality Complications Elevated ALT/AST common but hepatitis rare except in those with immune compromise Immune compromised – including HIV, on steroids or TNF antagonists - more likely to get crops of vesicles for weeks, need hospitalization, disseminated varicella, large hemorrhagic skin lesions, pneumonia, widespread disease with DIC Treatment Treatment – usually none except symptomatic for pruritis, fever, cut fingernails Avoid ASA as associated with Reyes syndrome Acyclovir (needs 10X levels as for HSV) not usually recommended for mild case – modest effects But safe and fewer lesions, reduced timing of new lesions and quicker healing and crusting Treat with Acyclovir recommended Treat > 12 yoa Secondary household cases (more severe) Chronic cutaneous or cardiopulmonary disorders Those on intermittent or inhaled steroids Those on chronic salicylates Disseminated disease with pneumonia or encephalitis Acyclovir In adult studies didn’t show much help. Some evidence suggests it helps outcome in varicella pneumonia. UpToDate recommends if can get within 24 hours of infection For immunocompromised or if complications serious give IV – otherwise 20 mg/kg/dose po 4-5 times/day for 5 days- 800 mg for adults Can cause GI Side Effects and HA Varicella in pregnancy Varicella more severe in pregnant women Mother to child transmission of VZ in utero, perinatally, or postnatally Varicella pneumonia more common in pregnancy so recommend acyclovir in pregnant women with varicella – appears to lower mortality from varicella pneumonia (Class B drug in pregnancy) Congenital varicella Congenital varicella syndrome – cutaneous scars, IGR, neurological, ocular and limb abnormalities. Newborn – Congenital varicella syndrome – most when mothers infected 8-20 weeks. Risk small: 2% < 20 weeks and 1% < 13 weeks. (0.4-2 %) Risk congenital varicella syndrome estimated with PCR of fetal blood or amniotic fluid + US for fetal abnormality If pregnant woman exposed, test serologically and give post exposure prophylaxis within 96 hours with VariZIG (up to 10 days) Neonatal varicella Neonatal varicella is serious illness - up to 30% mortality. At risk if mother had VZV within 2 weeks of delivery and worst if within 5 days of delivery If maternal VZV 21 days or more before delivery baby has passive IgG and should be ok. Often disseminated with pneumonia, hepatitis, meningoencephalitis VariZIG within first day may ameliorate – VariZIG prolongs incubation period If infant gets it after 10 days of age usually mild Acyclovir for newborn in severe disease Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever Not like others mentioned but can be fatal if missed. Rickettsial rickettsii U.S., Canada, Mexico, Central America and South America (Bolivia, Argentina, Brazil and Columbia) In one group of patients, 4533 cases: 25% hospitalized, 0.5% death Bite of tick – most 5-7 (2-14) days prior to illness Clinical Initially nonspecific: fever, HA, malaise, myalgias, arthralgias, abd. HA, abd. pain can be severe. 88-90% get rash (10% don’t – RM Spotless Fever) often does not start though till 2-3 day of illness Blanching erythematous rash with macules becoming petechial over time (varies) Begins on ankles heels, extremeties and goes inward On palms and soles characteristic Can be atypical or absent Treatment No reliable early test and treatment needs to be begin in first 5 days or mortality higher so treat on suspicion Doxycycline in adults AND children. UpToDate recommends chloroamphenicol for pregnant women Doxycycline: 100 po bid for most > 45 kg. 2.2 mg/kg/dose twice daily for children. For critically ill 200 mg po bid for 72 hours Treat 5-7 days – 3 days past last fever. http://sitemaker.umich.edu/mc5/rocky_mountain_spotted_fever Other less dangerous Rickettsia cause spotted fevers in other countries – fever, headache, intense myalgia and often rash. Clinical features to diagnose. Similar rash to RMSF Doxycycline for all – 100 twice daily. (children 2.2 mg/kg/dose every 12 hours) Other Exanthems - Dengue Rash begins towards end of febrile period and 2-5 days after symptoms appear in 50% of cases Confluent erythematous macular rash Extremities with scattered well circumscribed areas of sparing (“sea of red with islands of normal skin)” Tends to cover the body but spares the face – may involve the palms and soles. + tourniquet test or few spontaneous petechiae. http://www.emedicinehealth.com/dengue_fever/page2_em.htm Other exanthems – drug eruption Exanthematous, morbilliform, M-P drug eruption Symmetric macules, small papules 5-14 days after initiating drug or even after drug stopped Sooner within 1-2 days if previously exposed Occurs 2% of drug exposures; 2nd only to urticarial reactions Tend to involve trunk, proximal extremities – or whole body Can itch or produce low grade fever. Resolved 7-14 days. Tx: D/C meds - “treating through” sometimes indicated Treatment for rash – topical steroids, oral antihistamines Other exanthems – enteroviruses Non-polio Enteroviruses and Parechovirus viral rashes Ubiquitous viruses – fecal-oral spread Coxackieviruses A and B, echoviruses, enteroviruses 90% asymptomatic or undifferentiated febrile illness 10-15 million symptomatic infections / year in the U.S. If not hand foot and mouth disease not distinctive – mimic other exanthems and can be morbilliform Enterovirus Especially the echoviruses cause a M-P nonspecific rash. Often in multiple household members Mild Fever 24-36 hours – disappears with appearance of discrete, nonpruritic salmon-pink macules, papules < 1 cm on face and upper chest (sometimes face, proximal extremities). No need to isolate Other rashes - meningococcemia Meningococcemia – mentioned so as to not miss Fatal if missed > 50% of time begins with petechial 1-2 mm rash Trunk and lower portion of body Can begin with M-P rash resembling rubella for 1-2 days 15-25% get purpura fulminans – severe complication. Painful Acute onset cutaneous hemorrhage and necrosis Watch out for petechiae or hemorrhage with pain Other exanthems - typhoid Rash usually in second week of illness Called "rose spots" Faint salmon colored macules On trunk, abdomen http://pathmicro.med.sc.edu/infectious%20disease/typhoid%20spots.jpg Other exanthems Infectious mononucleosis 10-15% get pink-red maculopapular rash If given Ampicillin 80-90% develop bright red morbilliform rash HIV Secondary syphilis Leptospirosis Many others with similar appearance. Summary Measles is still a very important disease in the developing world with considerable morbidity and mortality. Giving Vitamin A may lower mortality. Most childhood exanthems recognized by progression of rash, other S/S rather than just a characteristic rash Be very wary of petechiae as they indicate a serious infection such as RMSF and meningococcemia. References Albrecht MA. “Clinical features of varicella-zoster virus infection: Chickenpox.” UpToDate accessed 12/24/2013. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-features-of-varicellazoster-virus-infectionchickenpox?source=search_result&search=chicken+pox&selectedTitle =1~150 Albrecht MA. “Epidemiology of varicella-zoster virus infection: Chickenpox.” UpToDate accessed 12/24/2013. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/epidemiology-of-varicella-zostervirus-infectionchickenpox?source=search_result&search=chicken+pox&selectedTitle =7~150 Albrecht MA. “Treatment of varicella-zoster virus infection: Chickenpox.” UpToDate accessed 12/24/2013. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-of-varicella-zostervirus-infectionchickenpox?source=search_result&search=chicken+pox&selectedTitle =2~150 Apicella, M. “Clinical manifestations of meningococcal infection.” UpToDate accessed 12/24/2013. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-manifestations-ofmeningococcalinfection?source=search_result&search=meningococcal&selectedTitle= 3~150 Barinaga JL, Skolnik PR. “Clinical presentation and diagnosis of measles.” UpToDate accessed 12/24/2103. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-presentation-anddiagnosis-ofmeasles?source=search_result&search=measles&selectedTitle=1~150 Barinaga JL, Skolnik PR. “Epidemiology and transmission of measles.” UpToDate accessed 12/24/2013. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/epidemiology-and-transmissionofmeasles?source=search_result&search=measles&selectedTitle=3%7E15 0 Barinaga JL, Skolnik PR. “Prevention and treatment of measles.” UpToDate accessed 12/24/2013. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/prevention-and-treatment-ofmeasles?source=search_result&search=measles&selectedTitle=2%7E15 0 Belamarich PR. “Measles and malnutrition.” Pediatrics in Review accessed 12/24/2103. http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/content/19/2/70 Bennett NJ. “Pediatric Enteroviral Infections.” Medscape reference accessed 12/24/2013. http://www.emedicine.medscape.com/article/9636370overview Bircher AJ. “Exanthematous (morbilliform) drug eruption.” UpToDate accessed 12/23/2013. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/exanthematous-morbilliformdrugeruption?source=search_result&search=exanthematous&selectedTitle =1%7E88 Caldararo S. “Measles.” Pediatrics in Review accessed 12/24/2013. http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/content/28/9/352 CDC. “2007 Guideline for Isolation Precautions: Preventing transmission of Infectious agents in healthcare settings.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention accessed 12/23/2013. www.cdc.gov/hicpac/2007ip/2007ip_appenda.html Chen SSP. “Measles.” Medscape Reference accessed 12/24/2013. emedicine.medscape.com/article/966220-overview Davis CP. “Dengue Fever.” emedicine health accessed 12/24/2014. http://www.emedicinehealth.com/dengue_fever/page2_em.htm Dodson SR. “Congenital rubella syndome: Clinical features and diagnosis.” UpToDate accessed 12/24/2013. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/congenital-rubella-syndromeclinical-features-anddiagnosis?source=search_result&search=rubella&selectedTitle=3%7E15 0 Edwards MS. “Rubella.” UpToDate accessed 12/24/2013. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/rubella?source=search_result&sea rch=rubella&selectedTitle=1%7E150 Fennelly GJ. “Vitamin A Supplementation and Measles.” Pediatrics in Review accessed 12/24/2013. http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/content/16/9/358 Gold E. “Almost extinct diseases: measles, mumps, rubella, and pertussis.” Pediatrics in Review accessed 12/24/2013. http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/content/17/4/120 Hartley AH and Rasmussen JE. “Infections Exanthems.” Pediatrics in Review accessed online a http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/content/9/10/321 Jordan JA. “Clinical Manifestations and pathogenesis of human parvovirus B19 infection.” UpToDate accessed 12/24/2013. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-manifestations-andpathogenesis-of-human-parvovirus-b19infection?source=search_result&search=b19&selectedTitle=1%7E122 Jordan JA. “Treatment and prevention of parvovirus B19 infection.” UpToDate accessed 12/24/2013. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-and-prevention-ofparvovirus-b19infection?source=search_result&search=b19&selectedTitle=3%7E122 Lam JM. “Characterizing Viral Exanthems.” Medscape accessed 12/24/2013. www.medscape.com/viewarticle/734882_print Mcgill AJ, Ryan ET, Hill DR, and Solomon, T (eds.). Hunter’s Tropical Medicine and Emerging Infectious Diseases 9th edition. China: Elsevier, Inc. 2013. 251-256 Modlin JF. “Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of enterovirus and parechovirus infections.” UpToDate accessed 12/24/2013. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-manifestations-anddiagnosis-of-enterovirus-and-parechovirusinfections?source=search_result&search=enterovirus&selectedTitle=1% 7E105 Pichichero ME. “Complications of streptococcal tonsillopharyngitis.” UpToDate accessed 12/24/2013. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/complications-of-streptococcaltonsillopharyngitis?source=search_result&search=scarlet+fever&select edTitle=1%7E22 Riley LE, Fernandes CJ. “Parvovirus B19 infection during pregnancy.” UpToDate accessed 12/24/2013. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/parvovirus-b19-infection-duringpregnancy?source=search_result&search=b19&selectedTitle=4%7E122 Riley LE. “Varicella-zoster virus infection in pregnancy. UpToDate accessed 12/24/2013. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/varicellazoster-virus-infection-inpregnancy?source=search_result&search=varicella&selectedTitle=4%7 E150 Sexton DJ. “Clinical Manifestations and diagnosis of Rocky Mountain spotted fever.” UpToDate accessed 12/24/2013. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-manifestations-anddiagnosis-of-rocky-mountain-spottedfever?source=search_result&search=rocky+mountain+spotted+fever&s electedTitle=1%7E46 Sexton DJ. “Other spotted fever group rickettsial infections.” UpToDate accessed 12/24/2013. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/otherspotted-fever-group-rickettsialinfections?source=search_result&search=spotted+fever&selectedTitle= 1%7E150 Sexton DJ. “Treatment of Rocky Mountain spotted fever.” UpToDate accessed 12/24/2013. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-ofrocky-mountain-spottedfever?source=search_result&search=spotted+fever&selectedTitle=3%7E 150 Speer ME. “Varicella-zoster infection in the newborn.” UpToDate accessed 12/24/2013. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/varicellazoster-infection-in-thenewborn?source=search_result&search=varicella&selectedTitle=6%7E1 50 Tremblay C, Brady MT. “Roseola infantum (exanthem subitum).” UpToDate accessed 12/24/2013. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/roseola-infantum-exanthemsubitum?source=search_result&search=roseola&selectedTitle=1%7E150 White SW. “Roseola Infantum.” Medscape Reference accessed 12/24/2013. emedicine.medscape.com/article/1133023-overview. van den Ent MMVX, Brown DW, Hoekstra EJ, Christie A, Cochi SL. “Measles Mortality Reduction Contributes Substantially to Reduction of All Cause Mortality Among Children Less than five years of age, 1990-2008. JID accessed 12/24/2013. http://www.unicef.org/immunization/files/Measles_Maya_ et_al_2011_S18.pdf WHO Media Centre. “Measles.” World Health Organization accessed 12/24/2013. http://www.who.ent/mediacentre/factsheets/fs286/en/ World Health Organization. “Treating measles in children.” World Health Organization accessed 12/20/2013. http://helid.digicollection.org/en/d/Jh0184e/1.html