* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

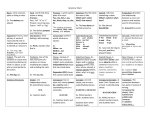

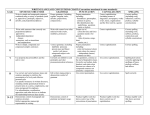

Download Into-English Grading Standards - American Translators Association

Old English grammar wikipedia , lookup

Chinese grammar wikipedia , lookup

Macedonian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Transformational grammar wikipedia , lookup

Modern Hebrew grammar wikipedia , lookup

French grammar wikipedia , lookup

Ancient Greek grammar wikipedia , lookup

Malay grammar wikipedia , lookup

Junction Grammar wikipedia , lookup

Scottish Gaelic grammar wikipedia , lookup

Esperanto grammar wikipedia , lookup

English clause syntax wikipedia , lookup

Preposition and postposition wikipedia , lookup

Polish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Romanian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Spanish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Latin syntax wikipedia , lookup

Pipil grammar wikipedia , lookup