* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Writings on the American Civil War

Opposition to the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Georgia in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

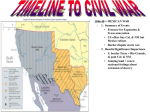

Secession in the United States wikipedia , lookup

Virginia in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Alabama in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Military history of African Americans in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Tennessee in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Origins of the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

South Carolina in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Mississippi in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Border states (American Civil War) wikipedia , lookup

United States presidential election, 1860 wikipedia , lookup

Union (American Civil War) wikipedia , lookup

United Kingdom and the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup