* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Document

5-HT3 antagonist wikipedia , lookup

Prescription costs wikipedia , lookup

Adherence (medicine) wikipedia , lookup

Neuropharmacology wikipedia , lookup

Pharmacogenomics wikipedia , lookup

Neuropsychopharmacology wikipedia , lookup

Theralizumab wikipedia , lookup

Dydrogesterone wikipedia , lookup

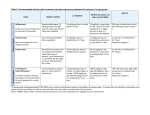

IN THE NAME OF GOD Seyed Alireza Haji seyed javadi MD Psychiatrist Assistant Professor and Head Department of Psychiatry school of Medicine Qazvin University of Medical Science Qazvin,Iran Email: [email protected] Telfax: + 98 28 33555054 تازه های دارویی در روانپزشکی داروهای ضد افسردگی Available Types of Pharmacotherapy Tricyclic antidepressants (TCA) MAOI’s SSRI’s SNRI’s Atypical antidepressants Antidepressants Mechanisem • Most antidepressants block the reuptake of a neurotransmitter of one or more of the bioamines: serotonin, norepinephrine, dopamine. Tricyclic Antidepressants • Available for more than 30 years • Act by NE and/or 5 HT presynaptic reuptake inhibition • Side effects include anticholinergic effects, orthostasis, slowing of cardiac conduction • Secondary better than tertiary compounds Chemistry • Tricyclic and tetracyclic compounds are categorized primarily on the basis of their chemical structure .The tricyclics have a three-ring structure, hence, their name. • The tertiary amine tricyclics, such as amitriptyline (Elavil) and imipramine, have two methyl groups at the end of the side chain. • These compounds can be demethylated to secondary amines, such as desipramine (Norpramin, Pertofrane) and nortriptyline (Aventyl, Pamelor). • The tetracyclic compounds, maprotiline (Ludiomil) and amoxapine (Asendin), have a four-ring central structure. • Five tertiary amines have been marketed in the United States— amitriptyline, clomipramine (Anafranil), doxepin (Sinequan), imipramine, and trimipramine (Surmontil). • The three secondary amine compounds are desipramine, nortriptyline, and protriptyline (Vivactil). Antidepressants Tricyclic: Tertiary Amines Amitriptyline (Elavil) Clomipramine (Anafranil) Doxepine (Sinequan) Imipramine (Tofranil) Trimipramine (Surmontil) Antidepressants Tricyclic: Secondary Amines Desipramine (Norpramin) Nortriptyline (Aventyl, Pamelor) Protryptyline (Vivactil) Antidepressants Tetracyclic Maprotiline (Ludiomil) Amoxapine (Asendin) Side Effects – TCAs • Most common uncomfortable side effects: – Sedation – Orthostatic hypotension – Anticholinergic • Others – – – – – Tremors Restlessness, insomnia, confusion Pedal edema, headache, and seizures Blood dyscrasias Sexual dysfunction • Adverse – Cardiotoxicity Effects of tricyclic antidepressants on Reuptake and 5-HT2 Tricyclic antidepressants 5-HT reuptake Noradrenaline reuptake 5-HT2 antagonism Tricyclic antidepressants Amitriptyline Clomipramine Desipramine Dothiepin Doxepin Imiprmine Lofipramine Nortriptyline + + ++ ? + + - + ++ + + + + + + ? + + Which one of the tricyclics is more selective on inhibiting reuptake of NE? Which one of the tricyclics is more selective on inhibiting reuptake of 5-HT? Side Effects of Tricyclic antidepressants Relative Side effects Amitriptyline Amoxapine Clomipramine Desipramine Dothiepin Doxepin Imipramine Lofepramine Nortriptyline Protriptyline Trimipramine Sedation Cardiotoxicity +++ ++ ++ + +++ +++ ++ + +++ + +++ ++ + +++ +++ ++ +++ + ++ +++ +++ Reuptake inhibition Hypotension +++ + ++ + ++ ++ +++ + 0/+ + ++ AntiCholinnergic +++ ++ ++ ++ ++ ++ +++ + ++ ++ ++ NE ++ +++ +/++++ + + + ++++ +++ ++++ + 5-HT +++ + +++ +/+ + +++ + + + + Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors: History: The anti TB Iproniazide exhibited mood elevating properties and latter found to inhibit MOA. Antidepressants Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors (MAOIs) • Action: Inhibits enzyme responsible for the metabolism of serotonin, dopamine, norepinephrine and tyramine • Increases levels of norepinephrine and serontonin in the CNS • Interacts with food – low tyramine diet Classifications of MAOIs Either: Hydralazine Derivatives (Phenelzine (Nardil®) Non –hydralazine DER.(Tranylcypramine (Parnate®) Or as irreversible non –selective (Phelzine and Tranylcypramine) vs reversible selective ( Mclobemide) Side Effects:↑ appetite (Phenelzine like) ↓ appetite (Tranylcypramine; hepatotoxicity; SLE like; Drug and Food interactions (very important). Drug Non-selective irreversible Selective reversible Sedation Anticholinergic Hypotensin effects Isocarboxazid + ++ + Phenelzine + ++ + Tranylcypromine - + + - - - Moclobemide Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors )SSRIs) Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors SSRIs – Fluoxetine (Prozac) – Sertraline (Zoloft) – Paroxetine (Paxil) – Fluvoxamine (Luvox) – Citalopram (Celexa) – Escitalopram (Lexapro) Side Effects – SSRIs • • • • • • • Headache Anxiety Transient nausea Vomiting Diarrhea Weight gain Sexual dysfunction SSRIs • Usually given in morning, unless sedation occurs • Higher doses, except fluoxetine, can produce sedation. • Paroxetine associated with weight gain Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors • • • • • Produce response rates close to 70% Safer and better tolerated than TCA’s Given once daily Starting and therapeutic doses often similar Most common side effects include GI symptoms, HA, insomnia, anxiety, and sexual dysfunction • Five available in the U.S. Effect of SSRIs on Reuptake and 5-HT2 5-HT reuptake Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors Citalopram Fluoxetine Fluvxamine Paroxetine Sertraline + + + + + Noradrenaline reuptake - 5-HT2 antagonists - What is the clinical significant of the antagonistic effect on 5-HT2 receptors? Side Effects of SSRI • Almost have no cardiovascular manifestations as compared to TCA. • Nausea and vomiting and decrease appetite How? • Insomnia and anxiety (with Fluoxetine ; Citalopram; but not with Paroxetine. So What? • Impotence and sexual dysfunction (in male and female) • Decrease weight. Dosing and Administration • In general, therapeutic effects are not dose related. • There are no data that suggest that the presence of therapeutic levels of any SSRI correlates with plasma levels and subsequent clinical response. • Nevertheless, patients may vary considerably in the amount of medication they need to derive clinical benefit. Fluoxetine • Fluoxetine is available in 10- or 20-mg pulvules, as 10-mg tablets, as 90-mg enteric-coated capsules for onceweekly administration, and as an oral concentrate of 20 mg/5 mL. • The suggested starting dose of fluoxetine in patients with major depression is 20 mg per day. Effective doses for the treatment of major depression have been reported, ranging from 5 to 80 mg per day in dose-finding trials. • Preclinical trials of fluoxetine in bulimia nervosa showed efficacy greater than placebo at 60 mg per day. • Treatment of OCD is also usually at higher doses than those used in major depression, with doses of 20 to 80 mg per day most commonly used. • Treatment of panic disorder is often initiated at less than 5 to 10 mg per day with a gradual upward dose titration. • Treatment of social anxiety disorder or premenstrual dysphoric disorder is often started at 10 to 20 mg per day. Dose is adjusted upward as needed. • Starting doses of 10 mg per day are often used in treating children, adolescents, or elderly patients. Adjustment upward is based on clinical response and tolerance of side effects. Citalopram and Escitalopram • Citalopram is available in 10-, 20-, and 40-mg-size tablets. The 20- and 40-mg-size tablets are scored. Citalopram is also available in an oral solution at a concentration of 10 mg/5 mL. Escitalopram is available in 10- and 20-mg-size tablets, both of which are scored. An oral solution of 5 mg/5 mL is available as well. • • The manufacturer recommends a starting dose for citalopram of 20 mg per day, with the expectation of generally increasing the dose to 40 mg per day, which, in clinical practice, is typically done after at least 1 week on the initial dosing. Highly anxious patients or those with increased sensitivities to side effects of medications may benefit from starting with the 10-mg tablet. The recommended starting dose of escitalopram is 10 mg per day. In clinical trials, the 20–mg-per-day dose did not offer any added benefit, but individual patients are often observed to benefit from the higher dose. If the dose is to be increased to 20 mg, this should generally occur no sooner than after 1 week on the initial dose. Because the 10-mg tablet is scored, 5 mg as a starting dose, if required, is available. • Many patients are observed to do well if citalopram or escitalopram is taken after meals for the first few days. After that period, they can take the medication with or without food. Sertraline • Sertraline is available in scored tablets of 25-, 50-, and 100-mg strengths. The oral concentrate is formulated at a concentration of 20 mg/mL with a12 percent alcohol content and must be diluted before use • Initial dosing for major depressive disorder and OCD is typically at 50 mg per day, with escalation to 100 mg per day after 4 to 7 days of treatment. • Initial treatment of panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, and PTSD is more typically 25 mg per day. • Children in OCD studies were started at 25 mg per day, whereas adolescents in OCD studies were started at 50 mg per day. • Treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder is usually started at 50 mg per day given daily or during the 2 weeks of the luteal phase. • Individual patients may demonstrate improved tolerability starting at lower doses. Not uncommonly, patients require an upward titration of the dose. • The dose range in most patients with anxiety or affective disorders is typically 100 to 200 mg a day, although some patients respond to 50 mg per day. Patients with OCD often require higher doses for full therapeutic effect. Fluvoxamine • • • • • Fluvoxamine is available in 25-, 50-, and 100-mg scored tablets and 100- and 150-mg controlled release capsules. Adults with OCD are often started at a dose of 50 mg administered at bedtime. The dose may be increased by 50 mg every 4 to 7 days. The effective dosing range in premarketing trials with OCD was 100 to 300 mg per day, although, clearly, some patients do respond to higher doses. The manufacturer suggests dividing the daily dose if it exceeds 100 mg per day, although many patients tolerate doses larger than 100 mg as a single dose. Initial upward titration is often easier with a split-dose regimen. Treatment of OCD in adolescents and children should start at 25 mg per day with 25–mgper-day increases every 4 to 7 days. The effective dosing range in premarketing studies was 50 to 200 mg per day. Adolescents often require a dose close to that used in adults, whereas children, perhaps owing to higher plasma fluvoxamine levels, may respond to the lower portion of the dosing range. Due its short half-life, total daily doses of fluvoxamine greater than 50 mg should be administered as a split dose. Using the controlled release formulation obviates this need for divided doses. Dosing for disorders other than those for which fluvoxamine is approved in the United States is usually initiated at 25 to 50 mg per day. Patients with major depressive disorder typically show responses over the range of 100 to 300 mg per day, although response is often seen in the range of 100 to 200 mg per day. Due to possible early activation of anxiety symptoms, treatment of panic disorder is best started at a dose of 25 mg per day for most patients, owing to increased sensitivity of side effects in this population. The typical effective dose is usually 100 to 200 mg per day. Paroxetine • Paroxetine HCl is available as 10-, 20-, 30-, and 40-mg-size tablets. The 20-mg-size tablets are scored. Paroxetine CR is available in 12.5-, 25-, and 37.5-mg tablets. Paroxetine is also available in an oral suspension at a concentration of 10 mg/5 mL. Paroxetine mesylate is available as10-, 20-, 30-, and 40-mg tablets. • The recommended starting dose for paroxetine is 20 mg per day for all approved indications, except in panic disorder, for which an initial dose of 10 mg per day is suggested. Starting paroxetine at 10 mg per day is also suggested for the elderly, medically ill, or those with significant renal or hepatic impairment. Paroxetine CR starting dose recommendations are similar, with 25 mg per day in major depressive disorder and 12.5 mg per day in patients with panic disorder, the elderly, the medically ill, or those with significant renal or hepatic impairment. Many clinicians find starting the more anxious or somatically preoccupied patient at a dose of 10 mg of paroxetine or 12.5 mg of paroxetine CR for a few days to be of benefit. • The target dose of paroxetine in the treatment of OCD is 40 mg per day, with most responders receiving 40 to 60 mg per day. Presumably, doses of paroxetine CR need to be approximately 25 percent higher. The patient's response to treatment of OCD is often slower than what is seen in major depressive disorder. Patients with panic disorder usually tolerate the side effects of paroxetine, like antidepressants in general, if started at a lower dose than is typically used in treating depression. Most panic disorder patients do better if started at an initial dose of 10 mg per day, with gradual titration to a target dose of 40 mg per day. Dose increases can be made at the rate of 10 mg per week. The maximal dose studied in premarketing clinical trials of paroxetine was 60 mg per day. The dosing strategy with paroxetine CR is similar, starting at 12.5 mg per week, and the maximal dose studied in clinical trials was 75 mg per day. • • Dosing for other disorders is usually done with an initial dose of 10 to 20 mg per day (12.5 to 25.0 mg per day for paroxetine CR) and a gradual upward titration. Paroxetine, like the other SSRIs, is well tolerated over a wide dosing range. Table 4: Side effects of SSRIs Drug Citalopram Fluoxetine Fluvoxamine Paroxetine Sertraline Cardiotoxicty ? _ _ _ Nausea ++ ++ +++ ++ ++ Anticholinergic effects _ _ _ + _ Sedation _ _ + ++ + Selective SerotoninNorepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors (SNRI) • The term serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) describes a group of medications that have therapeutic effects that are presumably mediated by concomitant blockade of neuronal serotonin (5-HT) and norepinephrine uptake transporters. • The SNRIs are also sometimes referred to as dual reuptake inhibitors, a broader functional class of antidepressant medications that includes tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) such as clomipramine and, arguably, imipramine and amitriptyline. • What distinguishes the SNRIs from TCAs is selectivity, which in this context refers to a relative lack of affinity for other receptors, especially muscarinic, histaminergic, and the families of α- and βadrenergic receptors. This distinction is an important one because the SNRIs have a more favorable tolerability profile than the older dual reuptake inhibitors. • • • • There are currently three SNRIs approved for use in the United States: Venlafaxine (Effexor and Effexor XR), desvenlafaxine succinate (Prestiq), duloxetine (Cymbalta). A fourth SNRI, milnacipran, is available in a number of countries, including France and Japan. Venlafaxine and Desvenlafaxine • Venlafaxine and desvenlafaxine are bicyclic phenylethylamine compounds that are structurally unrelated to other available antidepressants and anxiolytics. • First synthesized in the late 1970s, venlafaxine was found to block uptake of 5-HT and norepinephrine in vitro, with a greater affinity for the 5-HT transporter. Unlike the TCAs, venlafaxine was found to have virtually no affinity for muscarinic, histaminergic, or α- or β-adrenergic postsynaptic receptors. • Venlafaxine thus was predicted to exert antidepressant activity comparable to the prototypic dual reuptake inhibitors (i.e., amitriptyline and clomipramine), yet affording a safety and tolerability profile that was more similar to the SSRIs. Pharmacology • Venlafaxine and ODV inhibit neuronal uptake of 5-HT and, with significantly lower in vitro affinity, norepinephrine. In addition to a virtual lack of affinity for muscarinic, histamine 1 (H1), and adrenergic receptors, neither the parent drug nor the metabolite affect sodium fast channel activity. Venlafaxine and ODV do not inhibit the activity of the monoamine oxidase isoenzymes • Venlafaxine at higher doses also has been proposed to be a triple reuptake inhibitor on the basis of in vitro work documenting relatively weak inhibition of dopamine reuptake; ODV probably shares this property. • Venlafaxine and ODV are primarily eliminated by the kidneys. The elimination half-lives of venlafaxine and its metabolite are short (i.e., 4 and 10 hours, respectively). Therapeutic Indications • Venlafaxine is approved by the FDA for treatment of four therapeutic disorders: Major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, and panic disorder. • Major depressive disorder is currently the only FDA-approved indication for DVS. Depression • • • The recommended starting dose of both formulations of venlafaxine, 75 mg per day, is the minimum effective dose for treatment of depression. The IR formulation is available in five doses (25-, 37.5-, 50-, 75-, and 100-mg tablets) and should be administered with meals, on a two- or three-times-a-day basis. The XR formulation is available in 37.5-, 75-, and 150-mg capsules. The bulky capsules resulting from the microencapsulization process essentially precludes manufacture of larger-dose capsules. The minimum therapeutic dose of DVS is 50 mg per day. At the time of introduction, the drug will be available in 50- and 100-mg capsules. Venlafaxine XR and DVS may be taken in the morning or evening, with or without food, as clinically indicated. In ambulatory clinical trials of venlafaxine using flexible doses, a modal daily dose of 150 mg per day is typically observed, regardless of the formulation used. When therapy at modest doses is ineffective, further increases up to 375 mg per day can be considered, as tolerated. However, the maximum recommended daily dose of the XR formulation is only 225 mg because of a lack of data on oncedaily ingestion of higher dosages . Despite some concerns that noradrenergic activity may exacerbate anxiety, efficacy has been established in studies of depressed people with significant concomitant symptoms of anxiety. Generalized Anxiety Disorder • Venlafaxine XR received FDA approval for treatment of generalized anxiety disorder in 1999. Social Anxiety Disorder • The FDA approved venlafaxine for treatment of social anxiety disorder in early 2003 Other Psychiatric Disorders • • • There are numerous preliminary studies and case series pertaining to treatment of various other mood and anxiety disorders, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and other psychiatric disorders. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder may be thought of as a gender-specific form of brief recurrent depression, and it is known to be responsive to SSRIs. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study evaluated flexible doses of venlafaxine therapy (range from 50 to 200 mg per day) across four menstrual cycles among 157 women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder. There was significantly greater improvement in the venlafaxine group compared to the placebo group across measures of emotion, function, physical symptoms, and pain. As there is increasing evidence that 5-HT reuptake inhibitors are effective across the full range of anxiety syndromes, it would not be surprising if other indications were established for venlafaxine. With respect to panic disorder, efficacy is being evaluated in several ongoing double-blind, placebo-controlled studies. Despite the obvious parallels with clomipramine, the antiobsessional effects of venlafaxine have not been extensively studied. Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) represents another area of potential applicability. Tolerability • Venlafaxine has a safety and tolerability profile that approaches that of the more widely prescribed SSRI class. For example, in the pooled data set of Michael Thase and colleagues, 9 percent of venlafaxine-treated patients withdrew because of adverse events, as compared to 7 percent of SSRItreated patients. Hypertension • Higher-dose venlafaxine therapy is associated with an increased risk of sustained elevations of blood pressure. Experience with the IR formulation in studies of depressed patients indicated that sustained hypertension was dose related , increasing from 3 to 7 percent at doses of 100 to 300 mg per day and to 13 percent at doses greater than 300 mg per day. • When higher doses of the XR formulation are used, however, monitoring of blood pressure is recommended Discontinuation Syndrome • Venlafaxine is one of the antidepressants most commonly associated with a discontinuation syndrome • This syndrome is characterized by the appearance of a constellation of adverse effects during a rapid taper or abrupt cessation, including dizziness, dry mouth, insomnia, nausea, nervousness, sweating, anorexia, diarrhea, somnolence, and sensory disturbances. • As the XR formulation does not affect the elimination half-life of the compound, it does not decrease the potential for discontinuation symptoms. • It is recommended that, whenever possible, a slow taper schedule should be used when longer-term treatment must be stopped (e.g., reducing the daily dose by no more than 37.5 mg each week). • On occasion, substituting a few doses of the sustained-release formulation of fluoxetine may help to bridge this transition. Overdose • There were no overdose fatalities in premarketing trials, although electrocardiogram (ECG) changes (e.g., prolongation of QT interval, bundle branch block, QRS interval prolongation), tachycardia, bradycardia, hypotension, hypertension, coma, 5-HT syndrome, and seizures were reported. Fatal overdoses have been documented subsequently • venlafaxine had a significantly greater fatal toxicity index (a measure of overdose deaths per million prescriptions) than the SSRIs Duloxetine • Duloxetine hydrochloride is a propanamine compound that was synthesized in the 1980s by the same drug discovery team that identified the SSRI fluoxetine . • Like fluoxetine, duloxetine is a potent 5-HT uptake inhibitor and lacks affinity for muscarinic, histaminic, and α- and βadrenergic receptors. • Unlike fluoxetine, duloxetine is also a relatively potent inhibitor of norepinephrine reuptake and in in vitro studies duloxetine was found to be a substantially more potent norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor than venlafaxine. • Duloxetine was approved by the FDA for treatment of major depressive disorder in 2004; other indications include generalized anxiety disorder, fibromyalgia, and management of neuropathic pain associated with diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Pharmacology • Orally administered duloxetine is well absorbed, and peak plasma levels are achieved approximately 3 hours after ingestion. Duloxetine has no active metabolites and exhibits linear pharmacokinetics within a dose range of 20 to 120 mg. Steady-state concentrations are achieved within 3 days of oral dosing, and the drug has an elimination half-life of approximately 12 hours • In the plasma, approximately 90 percent of the drug is protein bound. After hepatic oxidation, metabolites of duloxetine are primarily eliminated by the kidneys. Duloxetine is a moderately potent inhibitor of the CYP 2D6 isoenzyme. Tolerability • The discontinuation rate due to adverse events in the studies summarized by Charles Nemeroff and colleagues was 15 percent in duloxetine-treated patients and 5 percent in placebo-treated patients. Side effect attrition was slightly higher in the duloxetine groups in the studies that used fluoxetine (10 vs. 6 percent) and paroxetine (14 vs. 10 percent) comparison groups, although these differences were not statistically significant in individual studies. • The most commonly reported side effects during duloxetine therapy were nausea (22 percent), dry mouth (16 percent), fatigue (11 percent), dizziness (11 percent), and somnolence (8 percent). • Incidence of sexual dysfunction appears to be comparable to that of the SSRIs. Of note, the incidence of nausea was similar for duloxetine (dosed twice daily) to fluoxetine and paroxetine (dosed every day) in head-to-head double-blind trials. Despite the drug's potential usefulness for treatment of urinary incontinence, urinary hesitancy and urinary retention were not common occurrences in studies of depressed patients. • Duloxetine therapy resulted in a small increase in resting pulse rate (approximately two beats per minute) and an average increase in blood pressure of approximately 2 mm Hg in the studies reviewed by Nemeroff and colleagues Milnacipran • The SNRI milnacipran is available in Japan and several European countries but, as of this time, is not being considered for introduction in the United States. • Milnacipran is distinguished as a dual reuptake inhibitor that (at least on the basis of in vitro studies) may be viewed as the converse of that of venlafaxine: • Specifically, milnacipran is approximately five times more potent for inhibition of norepinephrine uptake than for 5-HT reuptake inhibition. • Milnacipran thus could be thought of as a relatively selective norepinephrine uptake inhibitor at the minimum therapeutic dosage (50 mg per day) that exerts progressively greater inhibitory effects on 5-HT reuptake at higher doses (i.e., 250 mg per day). • Like the other SNRIs, milnacipran has virtually no affinity for muscarinic, histaminic, or α- and β-noradrenergic receptors Pharmacology • Milnacipran has a half-life of approximately 8 hours and shows linear pharmacokinetics between doses of 50 and 250 mg per day. Metabolized in the liver, milnacipran has no active metabolites. Milnacipran is primarily excreted by the kidneys. Most orally administered milnacipran is bioavailable, and only 13 percent of milnacipran is bound to plasma protein. Milnacipran is not thought to be a potent inhibitor of any of the CYP isoenzymes, although extensive studies have not been completed Antidepressant Efficacy • The countries that have approved milnacipran for general use as an antidepressant have not required completion of a large number of placebo-controlled studies, and, hence, efficacy is not as well established, as is the case for venlafaxine or duloxetine • Jean-Claude Bisserbe identified a number of RCTs contrasting milnacipran with various TCAs. The novel SNRI was reported to be as effective as imipramine, less effective than (at 50 mg per day) or comparable to (at 200 mg per day) amitriptyline, and less effective than (at 200 mg per day) or comparable to clomipramine. Three published, controlled comparisons against SSRIs were identified, as well as one relatively large, open-label comparison with fluvoxamine. Results of these trials tended to favor milnacipran for treatment of patients with more severe depressive symptoms. Tolerability • In comparative clinical trials, milnacipran therapy was associated with significantly fewer anticholinergic and antihistaminic side effects than the tertiary amine TCAs and fewer GI side effects than the SSRIs. Noteworthy side effects (i.e., incidence greater than an SSRI) included dizziness, sweating, and urinary hesitancy.. Like reuptake inhibitors, milnacipran should not be prescribed in proximity to a MAOI. Novel or Atypical Antidepressants • Bupropion (NE and DA reuptake inhibition??Dopamin increase) • Trazodone (5 HT2 alpha-ANT) • Nefazodone (Serzone) • Mirtazapine (presynaptic alpha 2 ANT and 5 HT2 and 5 HT3 ANT) Effects of atypical antidepressants on Reuptake and 5-HT2 Amoxapine Buproprion Maprotiline Mianserin Nafazodone Nomifensine Trazodone Venlafaxine 5-Ht reuptake Noradrenaline reuptake 5-HT2 antagonism -/+ ++ + + + + + + + + + - Side effects of atypical antidepressants Drug Mianserin Mirtazepine Nefazodone Trazodone Venlafaxine Toxicity + + Sedation ++ ++ + +++ ++ Hypotension + +++ - Anticholinergic effects + + + Bupropion • Originally introduced in the 1980s bupropion (Wellbutrin) has become one of the more commonly prescribed antidepressants in the United States. • As a result of a unique pharmacology, bupropion is often used as an alternative to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs). • In addition to its U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval in the treatment of depression, bupropion is also approved for smoking cessation and is the only antidepressant to receive FDA approval for the preventive treatment of seasonal affective disorder (SAD) • . Additionally, bupropion is used for numerous off-label indications including the treatment of attentiondeficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), sexual dysfunction, obesity, and fatigue related to nonpsychiatric medical condition. Dosing and Formulations • Bupropion hydrochloride is available in IR, SR forms. As of 2006, all of these formulations had become available as generics in the United States. • The usual starting dose in all formulations is 150 mg per day taken in the morning, but the IR form was often started at 100 mg twice a day. The average therapeutic dose of bupropion for the treatment of depression is 300 to 450 mg per day. • In smoking cessation, bupropion SR is typically started at 150 mg per day and then increased to the target dose of 300 mg per day. Side Effects • The pharmacodynamics effects of bupropion result in a side effect profile different from most antidepressants. Many of the adverse events reported with bupropion are associated with its noradrenergic, and to a lesser extent, dopaminergic effects. • Insomnia is one of the common side effects of bupropion, affecting at least 11 percent of patients in clinical trials. • Anxiety and agitation may occur as treatment emergent effects. • At least 6 percent of patients in clinical trials also experienced a mild to moderate tremor. • Treatment emergent psychotic symptoms have rarely been reported in depressed patients • Analysis of data sets revealed an enhanced risk of seizure in patients with a history of eating disorders, head trauma, or previous seizure disorder. Also, doses above 450 mg per day or 200 mg at one time (for the IR formulation) enhanced the risk of seizure. For extended release formulations at doses of 450 mg per day or less, the seizure risk is estimated at 0.1 to 0.2 percent, which is comparable to the rates reported with SSRIs and may be less than the rates reported with some TCAs and maprotiline (Novo-Maprotiline). Side Effects • Other common side effects reported in trials included nausea, dry mouth, excessive sweating, tinnitus, and rash. The most common reasons patients discontinued bupropion in acute clinical trials in depression were nausea and rash. • • Bupropion has a favorable cardiovascular profile with few cardiac effects. Bupropion is not known to have clinically significant effects on blood pressure, heart rate, or cardiac conduction. Thus, bupropion is commonly used in patients with known cardiac pathology. However, there have been rare reports of significant hypertension associated with bupropion in patients with and without a preexisting history of high blood pressure. Side effects common to many antidepressants (including sexual side effects and weight gain) appear uncommon with bupropion. • • • As noted earlier, bupropion has been associated with weight loss, and there are many reports of improved sexual functioning, including increased libido and arousal, with the drug. Other side effects such as hepatoxicity, hematopoietic changes, and severe headaches occur rarely in bupropion-treated patients. Thus, the side-effect profile makes bupropion an important alternative to many patients who cannot tolerate other antidepressants. Trazodone History • Trazodone was first marketed in Europe in the 1970s and received U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval in 1981 for the treatment of major depression in the United States. • Its improved safety and tolerability compared to TCAs was most likely responsible for trazodone's rapid rise in clinical use after its introduction. • However, with the increased popularity of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressants, trazodone has fallen out of favor as a first-line treatment for depression in the United States. Pharmacology Pharmacokinetics • Trazodone is absorbed efficiently by the human digestive tract after oral administration, reaching peak plasma concentration in about 1 hour. • When consumed with food, the total amount of drug absorption is increased, maximum plasma concentration is decreased, and time to peak concentration is doubled. Since some adverse effects such as dizziness are related to peak plasma levels, this strategy has been shown to increase tolerability. Effects on Specific Organs and Systems • In both premarketing trials and postmarketing surveillance, the adverse effects seen with trazodone therapy have generally been benign, • mostly limited to dry mouth, headache, nausea, drowsiness, fatigue, and dizziness, the latter in part secondary to orthostatic hypotension. • Unlike TCAs, trazodone is virtually devoid of anticholinergic side effects, including major cardiac conduction abnormalities, thus explaining its benign profile following overdose. • The adverse reaction for which trazodone is most widely recognized, although infrequent, is priapism Insomnia • In recent years, it has become a common practice for clinicians to utilize trazodone for the treatment of primary insomnia, depression-related insomnia, and insomnia experienced as an adverse effect of antidepressant treatment. • This practice is due to trazodone's sedating side-effect profile that is generally more favorable than that of benzodiazepine hypnotic agents. • The dosage can be easily titrated by patients to achieve an optimal balance between reducing sleep latency and nocturnal awakenings and minimizing next morning grogginess. Dosage and Administration • • • • • The manufacturer's package insert recommends initiating trazodone at 150 mg per day in divided doses, increasing by 50 mg per day in intervals of 3 to 4 days up to a maximum dose of 400 mg per day in outpatients and 600 mg per day in inpatients. Taking these considerations into account, the authors suggest initiating trazodone at 100 mg once daily at bedtime. A dosage increase of 50 mg per day in 4- to 7-day intervals, depending on sensitivity to side effects, will allow patients to achieve the therapeutic range of 150 to 300 mg within 2 to 4 weeks. As some patients may require higher doses for maximal benefit, further dose increases up to the maximum of 600 mg per day may be tried if partial efficacy is observed at lower doses. Note that these recommendations are limited to adults, as trazodone has not been tested in children. For the treatment of primary or medication-related insomnia, doses in the 50- to 100-mg range are usually sufficient. Trazodone is available in scored 50- and 100-mg tablets and in 150- and 300mg tablets that can be divided into halves or thirds for convenient dosing adjustment and administration. Nefazodone • Structurally related to trazodone but does not has the sedative effect and does not block α- adrenoceptors , however; it likes most SSRI inhibit P450 3A4 isoenzyme. Mirtazapine • Mirtazapine (Remeron) is a tetracyclic piperazinoazepine compound that was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1995 for treatment of depression. • Unlike most newer antidepressants, mirtazapine has virtually no effect on monoamine uptake. α2 – adrenoceptors antagonists • Rather, therapeutic effects are thought to be mediated by inhibition of α2-adrenergic receptors and blockade of postsynaptic serotonin type 2 (5-HT2) and type 3 (5-HT3) receptors. • First synthesized in the early 1980s, mirtazapine is related to one older antidepressant, mianserin (Tolvon). Pharmacology • Mirtazapine has a half-life of approximately 30 hours and reaches steady state after 6 days of therapy. • Linear pharmacokinetics are observed across the therapeutic dose range (i.e., 15 to 60 mg per day). • Mirtazapine is essentially completely absorbed after oral dosing, and food has little effect on the rate or extent of absorption. Approximately 85 percent of circulating drug is bound to plasma protein. Other Indications for Mirtazapine • Mirtazapine is not formally indicated for treatment of any other disorder. Nevertheless, mirtazapine may be useful the treatment of insomnia, panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), as well as autism and other pervasive developmental disorders. • A number of small studies and case series have evaluated the utility of mirtazapine in treating anxiety and depression in cancer patients. • The most common side effects reported during mirtazapine therapy are sedation, increased appetite, weight gain, and dry mouth. • When compared to SSRIs or SNRIs, mirtazapine therapy is associated with significantly lower rates of gastrointestinal disturbance and a lower incidence of treatment-emergent sexual dysfunction. ALIREZA HAJ SEYED JAVADI MD. PSYCHIATRIST ALIREZA HAJ SEYED JAVADI MD. PSYCHIATRIST