* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

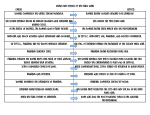

Download Battles of Cannae and Zama Readings

Military of ancient Rome wikipedia , lookup

Culture of ancient Rome wikipedia , lookup

Roman historiography wikipedia , lookup

Food and dining in the Roman Empire wikipedia , lookup

Berber kings of Roman-era Tunisia wikipedia , lookup

Education in ancient Rome wikipedia , lookup

Roman agriculture wikipedia , lookup

Structural history of the Roman military wikipedia , lookup

Romanization of Hispania wikipedia , lookup

Roman army of the late Republic wikipedia , lookup

Roman army of the mid-Republic wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Cannae Definition by Joshua J. Mark published on 20 December 2011 In 216 BCE, Roman military tactics were still in their infancy. AlthoughRome had won many impressive victories during the First Punic War, they continued to rely on their old tactic of placing a numerically superior force in the field to overwhelm the enemy. The typical Roman formation was to position light infantry toward the front masking the heavy infantry and then coordinating light and heavy cavalry on the back wings. This formation had worked well in Rome’s wars with theGreek King Pyrrhus who, although victorious at the Battle of Asculum (279 BCE), lost so many men that his army could not continue on to take the city. Pyrrhus used much the same strategy as the Romans did: he would place a large force in the field and rely on the superior numbers and the charge to break the Roman ranks. At the Battle of Cannae in 216 BCE, however, the Romans would learn an important lesson in military strategy from a general who fought like no other had before him. HANNIBAL'S SKILLS & ROME'S RESPONSE The Carthaginian general Hannibal started the Second Punic War when he attacked the city of Saguntum, a Roman ally, in southern Spain in 218 BCE. He then invaded northern Italy by marching his army across the Alps from Spain. Once descended onto the plains, he began advancing through Roman territory taking small cities and villages and defeating Roman forces twice; once at Trebia, at the Ticino River, and again at Lake Trasimene. By 217 BCE, Hannibal held all of northern Italy and the Roman senate feared he would march upon Rome. Little was being done, they felt, by the consulQuintus Fabius Maximus, who controlled the army and was following a policy of harassing Hannibal and thwarting his plans through strategic movements rather than full engagement. “IT WAS A SUPREME EXAMPLE OF GENERALSHIP, NEVER BETTERED IN HISTORY". DURANT In 216 BCE the consul Minucius Rufus was elected to command with Fabius and called for direct confrontation with the invading Carthaginian army. He was swiftly defeated by Hannibal who used tactics which the Roman command could not understand until it was too late. According to the historian Durant, “The Romans could not readily forgive him [Hannibal] for winning battles with his brains rather than with the lives of his men. The tricks he played upon them, the skill of his espionage, the subtlety of his strategy, the surprises of his tactics were beyond their appreciation” (48). With the defeat of Rufus, Rome scrambled to mobilize another force to take the field. THE BATTLE AT CANNAE The two consuls Lucius Aemilius Paulus and Caius Terentius Varro led a force of over 50,000 against Hannibal’s less than 40,000 and met him in battle at Cannae. Hannibal disguised his intentions by placing his light infantry of Gauls at the front to mask his heavier infantry whom he positioned in a crescent formation behind them. At a given signal just before battle, the light infantry fell back to form two wings of reserves. Hannibal’s light and heavy cavalry were positioned at the extreme wings of the position. The Romans, following their usual understanding of battle in which superior forces would overwhelm by sheer strength, arrayed their forces in traditional formation with light infantry masking the heavier and the cavalry also to the wings. Battle of Cannae - Destruction of the Roman Army When the Roman legions began their march toward the Carthaginian lines, the Carthaginian infantry fell back before them. The Romans took this as a positive sign that they were winning and pressed on. The Carthaginian light infantry, who had earlier fallen back, now took up position on either end of the crescent formed by their heavy infantry. At this same time the Carthaginian cavalry charged the Roman cavalry and engaged them. The Roman infantry continued their charge into the enemy’s ranks but, precisely because of their traditional formation, could make no use of their superior numbers. Those soldiers toward the back of the ranks merely served to push those before them onward. At the same time, the Carthaginian heavy cavalry drove back the Roman cavalry, opening a breach in the lines to the rear of the infantry. As the cavalry forces engaged, and as the Roman infantry continued its advance, Hannibal signaled for the trap to close. The light infantry which formed the ends of the crescent of the Carthaginian line now moved up to form an alley in which the Roman forces found themselves trapped. The Carthaginian cavalry fell upon the Roman infantry from behind, the light infantry attacked from the flanks, and the heavy infantry engaged from the front. The Romans were surrounded and were almost completely annihilated. Out of the over 50,000 who took the field, 44,000 were killed and 10,000 managed to escape to Canusium. Hannibal lost 6,000 men, mostly the Gauls, who had made up the front lines. THE AFTERMATH According to Durant, “It was a supreme example of generalship, never bettered in history. It ended the days of Roman reliance upon infantry and set the lines of military tactics for two thousand years” (51). Among those Romans who escaped Cannae was the twenty-year old Publius Cornelius Scipio. Scipio would remember Hannibal’s tactics at Cannae and, further, would study his other successful engagements. Fourteen years later, at the Battle of Zama in 202 BCE, Scipio would use Hannibal’s own tricks to defeat him and win the Second Punic War. Roman skill on the battlefield, through which they became masters of the world, can be traced directly back to Scipio Africanusand his adaptations of Hannibal’s strategies at Cannae. Battle of Zama, (202 BCE), victory of the Romans led by Scipio Africanus the Elder over the Carthaginians commanded byHannibal. The last and decisive battle of the Second Punic War, it effectively ended both Hannibal’s command of Carthaginian forces and also Carthage’s chances to significantly oppose Rome. The battle took place at a site identified by the Roman historian Livy as Naraggara (now Sāqiyat Sīdī Yūsuf, Tunisia). The name Zama was given to the site (which modern historians have never precisely identified) by the Roman historian Cornelius Nepos about 150 years after the battle. By the year 203 Carthage was in great danger of attack from the forces of the Roman general Publius Cornelius Scipio, who had invaded Africa and had won an important battle barely 20 miles (32 km) west of Carthage itself. The Carthaginian generals Hannibal and his brother Mago were accordingly recalled from their campaigns in Italy. Hannibal returned to Africa with his 12,000-man veteran army and soon gathered a total of 37,000 troops with which to defend the approaches to Carthage. Mago, who had sustained battle wounds during a losing engagement in Liguria (near Genoa), died at sea during the crossing. Scipio, for his part, marched up the Bagradas (Majardah) River toward Carthage, seeking a decisive battle with the Carthaginians. Some of Scipio’s Roman forces were reinvigorated veterans from Cannae who sought redemption from that disgraceful defeat. Once his allies had arrived, Scipio had about the same number of troops as Hannibal (around 40,000 men), but his 6,100 cavalrymen, led by the Numidian ruler Masinissa and the Roman general Gaius Laelius, were superior to the Carthaginian cavalry in both training and quantity. Because Hannibal could not transport the majority of his horses from Italy, he was forced to slaughter them to keep them from falling into Roman hands. Thus, he could field only about 4,000 cavalry, the bulk of them from a minor Numidian ally named Tychaeus. Hannibal arrived too late to prevent Masinissa from joining up with Scipio, leaving Scipio in a position to choose the battle site. That was a reversal of the situation in Italy, where Hannibal had held the advantage in cavalry and had typically chosen the ground. In addition to utilizing 80 war elephants that were not fully trained, Hannibal was also compelled to rely mostly upon an army of Carthaginian recruits that lacked much battle experience. Of his three battle lines, only his seasoned veterans from Italy (between 12,000 to 15,000 men) were accustomed to fighting Romans; they were positioned at the rear of his formation. Before the battle, Hannibal and Scipio met personally, possibly because Hannibal, perceiving that battle conditions did not favour him, hoped to negotiate a generous settlement. Scipio may have been curious to meet Hannibal, but he refused the proposed terms, stating that Carthage had broken the truce and would have to face the consequences. According to Livy, Hannibal told Scipio, “What I was years ago at Trasimene and Cannae, you are today.” Scipio is said to have replied with a message for Carthage: “Prepare to fight because evidently you have found peace intolerable.” The next day was set for battle. As the two armies approached each other, the Carthaginians unloosed their 80 elephants into the ranks of the Romaninfantry, but the great beasts were soon dispersed and their threat neutralized. The failure of the elephant charge can likely be explained by a trio of factors, with the first two being well documented and most important. First, the elephants were not well trained. Second—and perhaps even more vital to the outcome—Scipio had arranged his forces in maniples (small, flexible infantry units) with broad alleys between them. He had trained his men to move to the side when the elephants charged, locking their shields and facing the alleys as the elephants passed by. That caused the elephants to run unimpeded through the lines with little, if any, engagement. Third, the loud shouts and blaring trumpets of the Romans may have disconcerted the elephants, some of which swerved to the side early in the battle and instead attacked their own infantry, causing chaos on the front line of Hannibal’s recruits. Scipio’s cavalry then charged the opposing Carthaginian cavalry on the wings; the latter fled and were pursued by Masinissa’s forces. The Roman infantry legions then advanced and attacked Hannibal’s infantry, which consisted of three consecutive lines of defense. The Romans crushed the soldiers of the first line and then those of the second. However, by that time the legionnaires had become nearly exhausted—and they had yet to close with the third line, which consisted of Hannibal’s veterans from his Italian campaign (i.e., his best troops). At that crucial juncture, Masinissa’s Numidian cavalry returned from their rout of the enemy cavalry and attacked the rear of the Carthaginian infantry, who were soon crushed between the combined Roman infantry and the cavalry assault. Some 20,000 Carthaginians died in the battle, and perhaps 20,000 were captured, while the Romans lost about 1,500 dead. The Greek historian Polybius states that Hannibal had done all that he could as a general in battle, especially considering the advantage held by his opponent. That Hannibal was fighting from a position of weakness does not in any way diminish Scipio’s victory forRome, however. With the defeat of Carthage and Hannibal, it is likely that Zama awakened in Rome a vision of a larger future for itself in the Mediterranean. The Battle of Zama left Carthage helpless, and the city accepted Scipio’s peace terms whereby it ceded Spain to Rome, surrendered most of its warships, and began paying a 50-year indemnity to Rome. Scipio was awarded the surname Africanus in tribute of his victory. Hannibal escaped from the battle and went to his estates in the east near Hadrumetum for some time before he returned to Carthage. For the first time in decades, Hannibal was without a military command, and never again did he lead Carthaginians into battle. The indemnity Rome set as payment from Carthage was 10,000 silver talents, more than three times the size of the indemnity demanded at the conclusion of the First Punic War. Although the Carthaginians had to publicly burn at least 100 ships, Scipio did not impose harsh terms on Hannibal himself, and Hannibal was soon elected as suffete (civil magistrate) by popular vote to help administer a defeated Carthage. Conclusively ending the Second Punic War with a decisive Roman victory, the Battle of Zama must be considered one of the most important battles in ancient history. Having staged a successful invasion of Africa and having vanquished its canniest and mostimplacable foe, Rome began its vision of a Mediterranean empire.