* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

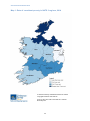

Download Social Inclusion Monitor 2014

Social Bonding and Nurture Kinship wikipedia , lookup

Sociological theory wikipedia , lookup

Social theory wikipedia , lookup

Development theory wikipedia , lookup

Unilineal evolution wikipedia , lookup

Origins of society wikipedia , lookup

Social history wikipedia , lookup

History of the social sciences wikipedia , lookup

Social exclusion wikipedia , lookup

Community development wikipedia , lookup

Working poor wikipedia , lookup