* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Parts of a Sentence File

Arabic grammar wikipedia , lookup

Udmurt grammar wikipedia , lookup

Swedish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Lithuanian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Macedonian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Scottish Gaelic grammar wikipedia , lookup

Navajo grammar wikipedia , lookup

Serbo-Croatian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Malay grammar wikipedia , lookup

Esperanto grammar wikipedia , lookup

English clause syntax wikipedia , lookup

Zulu grammar wikipedia , lookup

Japanese grammar wikipedia , lookup

French grammar wikipedia , lookup

Lexical semantics wikipedia , lookup

Ancient Greek grammar wikipedia , lookup

Portuguese grammar wikipedia , lookup

Italian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Modern Hebrew grammar wikipedia , lookup

Kannada grammar wikipedia , lookup

Yiddish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Georgian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Icelandic grammar wikipedia , lookup

Turkish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Chinese grammar wikipedia , lookup

Polish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Latin syntax wikipedia , lookup

Pipil grammar wikipedia , lookup

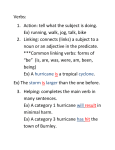

Parts of a Sentence Compliments of CMHS Staff Complete Sentence A sentence is a grammatically complete group of words that expresses a thought. Must perform 2 functions: Tell you the noun that the sentence is about Tell you what that noun does or is A sentence fragment is a group of words that is not grammatically complete DON’T DO IT! A sentence always have one of four purposes… 1. Declarative sentences make a statement. They end with a period. The show lasted three hours. 2. Imperative sentences make a command or a request. They end with either a period or (if the command shows strong feeling) an exclamation point. Please sing “I Love My Sneakers More Than Her” again. 3. Interrogative sentences ask a question. They end with a question mark. What is your favorite song? 4. Exclamatory sentences express strong feeling. They end with an exclamation point. Hey! You spilled my soda! Subject and Predicate Every sentence must have two parts: a subject and a predicate. The subject of a sentence names the person, thing, or idea that the sentence is about. The predicate of a sentence tells what the subject does, what the subject is, or what happens to the subject. A subject and a predicate may be a single word or a groups of words. Ex: Joe studies. The president of the senior class will study architecture in college Keep It “Simple” The simple subject is the key word or words in the subject. When a proper noun or a compound noun is a simple subject, it may be more than one word. The complete subject is made up of the simple subject and all of its modifiers (such as adjectives and prepositional phrases). Pizza at Vinnie’s Mushrooms or onions Vinnie That low price Keep It “Simple” Again The simple predicate is always one or more verbs or verb phrases that tell something about the subject. The complete predicate contains the verb or verbs and all modifiers (such as adverbs and prepositional phrases), objects, and complements. …tastes better these days. …are extra and cost more. …now charges ten dollars for a pie. …will not last long. Finding the Subject In an inverted sentence, the verb (v) comes before the subject (s). Used for poetic reasons or to build suspense. Ex: Over the castle’s walls stormed (v) the knights (s). The words here and there are very seldom the subject of a sentence. In a sentence beginning with either, look for the subject after the verb. Ex: Here is (v) the front-door key (s). The subject of a sentence is never part of a prepositional phrase. Ex: The areas (s) of most geometric figures are simple to calculate. Finding the Subject Again To find the subject of a question, turn the question into a statement. Ex: What color is (v) your dress (s)? Your dress (s) is (v) what color. In a command or request (an imperative sentence), the subject is always you (the person being spoken to). Ex: [You] Please leave the kingdom. Even when you mention the name of the person being spoken to, the subject is still understood to be you. Ex: Alex, [you] stop that this minute! Correcting Fragments Use three strategies to correct fragments while revising and editing: 1. Attach it. Join the fragment to a complete sentence before or after it. Fragment Located along the Nile south of Egypt. Nubia was largely unknown to the ancient Greeks and Romans. Revised Located along the Nile south of Egypt, Nubia was largely unknown to the ancient Greeks and Romans. Correcting Fragments Again 2. Add some words. Introduce the missing subject, verb, or whatever other words are necessary to make the group of words grammatically complete. Fragment The wealthy region. Wondrous goods such as ebony, ivory, panther skins traveled north in abundance. Revised The wealthy region offered wondrous goods such as ebony, ivory, panther skins traveled north in abundance. Correcting Fragments Again 3. Drop or replace some words. Drop the relative pronouns or subordinating conjunction that creates a fragment. Fragment The Nubian warriors who were very skilled with the bow and arrow. Revised The Nubian warriors were very skilled with the bow and arrow. Correcting Run-on Sentences A run-on sentence is made up of two or more sentences that are incorrectly run together as a single sentence. A run-on with no punctuation separating its sentences is called a fused sentence; a run-on with only a comma separating its sentences is called a comma splice. Here are five strategies that effective writers use to avoid or to correct run-on sentences: 1. Separate them. Add end punctuation and a capital letter to separate the sentences. No: Corals are invertebrates, they are related to jellyfish. Yes: Corals are invertebrates. They are related to jellyfish. 2. Use a conjunction. Use a coordinating or correlative conjunction preceded by a comma. No: Corals form colonies that cover more than 200,000 square miles of sea floor, Australia’s 1,250-mile-long Great Barrier Reef is one of their creations. Yes: Corals form colonies that cover more than 200,000 square miles of sea floor, and Australia’s 1,250-mile-long Great Barrier Reef is one of their creations. 3. Insert a semicolon. Use a semicolon to separate the two sentences No: Modern species of coral evolved about 230 million years ago they have changed little since then. Yes: Modern species of coral evolved about 230 million years ago; they have changed little since then. 4. Add a conjunctive adverb. Use a semicolon together with either a conjunctive adverb or a transitional expression. Be sure to put a comma after the conjunctive adverb. No: Coral reefs provide food for fish, they are home to starfish, crabs, eels, sea slugs, and sponges. Yes: Coral reefs provide food for fish; in addition, they are home to starfish, crabs, eels, sea slugs, and sponges. 5. Create a clause. Turn one of the sentences into a subordinate clause. No: Individual corals are the size of chocolate chips, they can build some of the largest solid structures on Earth. Yes: Although individual corals are the size of chocolate chips, they can build some of the largest solid structures on Earth Direct and Indirect Objects A direct object (DO) is a noun or pronoun that receives the action of an action verb. A direct object answers the question whom or what following the verb. Jerome carried his backpack (DO) to school. [He carried—what?—a backpack.] We spotted the ranger (DO) and the horse (DO) by the falls. [We spotted—whom or what?—the ranger and the horse.] More Object Stuff When an action verb is followed by an object, the verb is called transitive. Ex: The pitcher threw a curveball (DO) and then a slider (DO). When an action verb stands without an object, the verb is called intransitive. Ex: He threw more powerfully than ever before. More Stuff An indirect object (IO) is a noun or pronoun that answers the question to whom or for whom or to what or for what following an action verb. Ex: She gave me (IO) the assignment (DO). [She gave the assignment—to whom?—to me.] Ex: I gave the wall (IO) and ceiling (IO) one more coat (DO) of paint. [I gave one more coat—to what?—to the wall and ceiling.] A twist The following sentences have the same meaning, but only the first sentence has an indirect object—Jack. The second sentence includes to Jack, a prepositional phrase, not an indirect object. Please show Jack (IO) the test scores (DO). Please show the test scores (DO) to Jack. Subject Complement A linking verb needs a subject complement—a noun, pronoun, or adjective—after it in order to express a complete thought. The woman standing next to the car is its owner. Yes, the owner is she. She appears lost. Predicate Nominatives and Predicate Adjectives A subject complement that is a noun or pronoun is called a predicate nominative (PN). A predicate nominative is a noun or pronoun that follows a linking verb (LV) and renames or identifies the subjects. Ex: The grand slam (s) was (LV) his (PN). [His is a pronoun that identifies the subject, grand slam.] Common Linking Verbs: appear, become, fell, grow, look, remain, seem, smell, sound, taste, turn More Predicates A subject complement that is an adjective is called a predicate adjective (PA). A predicate adjective is an adjective that follows a linking verb and modifies, or describes, the subject. Ex: The speech (s) was (LV) brief (PA) but powerful (PA). [Brief and powerful are adjectives that modify the subject, speech.] Object Complements An object complement (OC) is a noun, pronoun, or adjective that follows the direct object (DO) and identifies or describes it. Ex: The class elected me (DO) president (OC). Ex: The news made him (DO) upset (OC) and frantic (OC). The following verbs (and any of their synonyms) can take object complements: appoint, call, choose, consider, cut, elect, find, make, name, paint, sweep, think Done. Happy Face.