* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download - Free Documents

Coronary artery disease wikipedia , lookup

Heart failure wikipedia , lookup

Electrocardiography wikipedia , lookup

Cardiac surgery wikipedia , lookup

Cardiac contractility modulation wikipedia , lookup

Myocardial infarction wikipedia , lookup

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy wikipedia , lookup

Quantium Medical Cardiac Output wikipedia , lookup

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia wikipedia , lookup

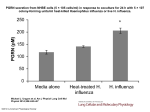

A Dominant Role of Cardiac Molecular Motors in the Intrinsic Regulation of Ventricular Ejection and Relaxation Aaron C. Hinken and R. John Solaro You might find this additional info useful... This article cites articles, of which can be accessed free at http//physiologyonline.physiology.org/content///.full.htmlreflist This article has been cited by other HighWire hosted articles, the first are Effects of ActinMyosin Kinetics on the Calcium Sensitivity of Regulated Thin Filaments Nicholas M. Sich, Timothy J. ODonnell, Sarah A. Coulter, Olivia A. John, Michael S. Carter, Christine R. Cremo and Josh E. Baker J. Biol. Chem., December , . Abstract Full Text PDF Downloaded from physiologyonline.physiology.org on May , Physiology , . doi./physiol.. A Novel, Insolution Separation of Endogenous Cardiac Sarcomeric Proteins and Identification of Distinct Charged Variants of Regulatory Light Chain Sarah B. Scruggs, Rick Reisdorph, Mike L. Armstrong, Chad M. Warren, Nichole Reisdorph, R. John Solaro and Peter M. Buttrick Mol Cell Proteomics, September , . Abstract Full Text PDF Rebuttal from Shmuylovich, Chung, and Kovacs J Appl Physiol, August , . Full Text PDF The curious role of sarcomeric proteins in control of diverse processes in cardiac myocytes R. John Solaro, Katherine A. Sheehan, Ming Lei and Yunbo Ke J Gen Physiol, July , . Full Text PDF Multiplex Kinase Signaling Modifies Cardiac Function at the Level of Sarcomeric Proteins J. Biol. Chem., October , . Full Text PDF Updated information and services including high resolution figures, can be found at http//physiologyonline.physiology.org/content///.full.html Additional material and information about Physiology can be found at http//www.theaps.org/publications/physiol This infomation is current as of May , . Physiology formerly published as News in Physiological Science publishes brief review articles on major physiological developments. It is published bimonthly in February, April, June, August, October, and December by the American Physiological Society, Rockville Pike, Bethesda MD . Copyright by the American Physiological Society. ISSN , ESSN . Visit our website at http//www.theaps.org/. PHYSIOLOGY , ./physiol.. REVIEWS Aaron C. Hinken and R. John Solaro Department of Physiology and Biophysics and Center for Cardiovascular Research, College of Medicine, University of Illinois at Chicago, Illinois solarorjuic.edu A Dominant Role of Cardiac Molecular Motors in the Intrinsic Regulation of Ventricular Ejection and Relaxation Molecular motors housed in myosins of the thick filament react with thinfilament actins and promote force and shortening in the sarcomeres. However, other actions of these motors sustain sarcomeric activation by cooperative feedback mechanisms in which the actinmyosin interaction promotes thinfilament activation. Mechanical feedback also affects the actinmyosin interaction. We discuss current concepts of how these relatively underappreciated actions of molecular motors are responsible for modulation of the ejection time and isovolumic relaxation in the beating heart. Downloaded from physiologyonline.physiology.org on May , In this review, we consider novel and, in our judgment, underappreciated aspects of the role of sarcomeric myosin motors cross bridges in regulation of the heart beat. Relatively recent and compelling evidence has substantially expanded the limited textbook view of the role of cross bridges in the heart beat and in regulation of contractility. One aspect of this textbook view is that cross bridges react with actin and undergo state transitions powered by the free energy of MgATP hydrolysis that lead to a mechanical transition impelling thin filaments toward the center of the sarcomere. A second textbook view is that the actin crossbridge reaction is inhibited at diastolic levels of sarcoplasmic Ca and released from this inhibition when Ca concentration increases in the sarcomeric space and Ca binds to troponin C cTnC. In basal metabolic states, not all available cross bridges are engaged in the actinmyosin interaction, and thus a third textbook view is that major control of contractility occurs with variations in the number of cross bridges engaged in the forcegenerating reaction with thin filaments. In this perspective, the level of contractility is governed largely by the amounts and rates of movements of Ca to and from the sarcomeres. Our expanded view of the role of the molecular motors in the heart beat includes processes intrinsic to the sarcomeres that are significant in sustaining myocardial stiffness during ejection and determining the rate of isovolumic relaxation. We discuss evidence indicating that these cooperative and mechanical feedback mechanisms are intrinsic to the sarcomeres and do not directly depend on membranecontrolled fluxes of Ca. We think this perspective of regulation of systolic mechanics and relaxation reorients thinking with regard to regulation of cardiac function from a focus on cellular Ca fluxes to a focus on regulation of processes at the level of the sarcomeres. Central to these regulatory processes is a role of cardiac molecu lar motors beyond simple promotion of force generation and shortening. It is now evident that, following the triggering of activation by Ca binding to cTnC, molecular motors are actively engaged in inducing and sustaining activation of the thin filaments. Moreover, the strain on active cross bridges, which occurs during ejection, and the rates of detachment of cross bridges are also important elements in determining the duration of systole and the rate of isovolumic relaxation. We discuss evidence that the kinetics of these sarcomeric processes are rate limiting during the cardiac cycle and modified by phosphorylation of regulatory proteins, especially cardiac myosin binding protein C MyBPC and the thinfilament regulatory protein cardiac troponin I cTnI. Finally, discussion is provided regarding evidence that the kinetics of molecular motors by drugs targeted to myosin represents a novel therapeutic approach in treatment of heart failure. Structure and Regulation of Cardiac Molecular Motor Activity The molecular motor of heart muscle is a highly asymmetrical protein consisting of two myosin heavy chains MHCs FIGURE and two pairs of myosin light chains FIGURE illustrates one MHC. The MHC has a globular head, containing both the actin binding site and the ATP binding and catalyzing site at the NH terminus of the protein. An helical COOHterminal tail interacts with another MHC in a coiledcoil motif that combines with rod portions of neighboring myosins to form the thickfilament backbone. There are two types of MHC expressed in mammalian myocardium, MHC and MHC, existing as dimers first described by Hoh et al. and termed V, V, and V. MHC generates about three times higher actinactivated ATPase activities, maximal filament / . Int. Union Physiol. Sci./Am. Physiol. Soc. REVIEWS sliding velocity, and greater peak power output than those preparations containing MHC , , , , , , , , . MHC, however, has been reported to produce twice the crossbridge force per ATPase cycle as MHC, meaning it consumes less energy to maintain a given force or a lower tension cost , , , , . Expression of these isoforms is species dependent and both developmentally and hormonally regulated with V myosin, a MHC homodimer predominately expressed during early development of all mammals and remaining high throughout life in humans and other large mammals. The V cardiac myosin, a MHC homodimer, predominates in mammalian hearts soon after birth and remains high throughout life in rats and mice . The helical tail region MHC interacts noncovalently with the light chains, consisting of one regulatory light chain RLC and one essential light chain ELC. The light chains are located toward the neck region of S and help to stabilize the neck and may confer some regulation of functional activity , such as increasing Ca sensitivity of force and the rate of force development see Ref. for a review. The thick filament also contains MyBPC FIGURE . It has been postulated that the presence of MyBPC can alter Casensitivity of force , rates of force development, and power output . These functional effects have been proposed to involve the interactions between the lever arm of MHC and MyBPC, thereby constraining movements of the myosin head and affecting the probability of binding to actin FIGURE . Thick and ThinFilament States in the Cardiac Cycle As depicted in FIGURE , myosin cross bridges cyclically interact with actin in a process coupled to the hydrolysis of ATP, which drives myocardial force generation and contraction. Cross bridges are initially in a weakly bound, nonforcegenerating rest state state , FIGURE during diastole. FIGURE shows a thinfilament regulatory unit RU consisting of actintroponintropomyosin in a ratio. Troponin Tn is a heterotrimer consisting of cTnC, cTnI, and cTnT. In the rest state, there is no Ca bound to regulatory sites on cTnC cTnI forms a complex with both actin and cTnT and thus reduces the reactivity of actin for myosin and holds tropomyosin in a position that blocks the crossbridge binding sites on actin , . The triggering of force generation and contraction is governed by Ca fluxes determined by the dynamics of electrochemical coupling of Ca release and Ca binding to cTnC. Cross bridges and thin filaments now enter into a transition state state FIGURE Downloaded from physiologyonline.physiology.org on May , FIGURE . Schematic illustrating the state of cross bridges in the cycle from rest to active states Thinfilament actins are shown with regulatory proteins tropomyosin Tm and troponin Tn with the Cabinding unit cTnC shown in red, the Tmbinding unit cTnT in blue, and the inhibitory unit cTnI in green. Thickfilament cross bridges XB are shown with myosin heavy chain MHC and light chains LC together with myosin binding protein C MyBPC and titin. See text for further description of the cycle and interpretation of the rate constants. PHYSIOLOGY Volume April www.physiologyonline.org REVIEWS determined by the on kCa and off rates kCa for Ca exchange with cTnC. This transition state involves altered interactions between TnI and actin, increased binding of cTnI to cTnC, and a cTnTdependent shift in Tm from its blocking position on the thin filament. These changes in the thin filament permit a shift in cross bridges toward strongly bound, forcegenerating states state FIGURE . The transition state is homologous to other crossbridge models whereby a myosin head has a full compliment of ATP hydrolysis products ADP and Pi bound and Ca bound at the thin filament. The state tostate transition FIGURE kXB and kXB from weakbinding, nonforcegenerating cross bridges to strongbinding, forcegenerating states is regulated by the kinetics inherent to cross bridges. The ratelimiting kinetic transition determining the shift toward the active state appears to be dependent on the load on the muscle with loads near peak power output similar to those encountered during ejection determined by the release of Pi and loads more near isometric such as occur during isovolumic contraction and relaxation determined by ADP release . An important aspect of state is that strongly bound cross bridges also induce cooperative activation of the thin filament by an increase in the affinity of cTnC for Ca , , . In addition to this cooperative process within an RU, there is also a cooperative activation of near neighbor RU transmitted through endtoend interactions between contiguous Tm strands and possibly through actinactin interactions as reviewed in Refs. , , . This mechanism of propagated activation appears to be particularly important in cardiac compared with skeletal muscle, where relatively small changes in strongly bound cross bridges have significant effects on Ca sensitivity of force and crossbridge kinetics , . A consequence of these cooperative mechanisms is illustrated by state in FIGURE , which indicates a population of cross bridges that remain in the active, forcegenerating state despite the loss of bound Ca. As discussed below, the lifetime of state is an important determinant of the duration of ejection. Inasmuch as the kinetic transition between states and and state to to some extent is dependent on crossbridge feedback, mechanisms that alter the number of active cross bridges will alter this transition. Processes that may potentially modify the number of active cross bridges include the sarcomere length, as determined by the enddiastolic volume, the strength of the interaction energies determining cooperativity within and between RU, and stretchinduced activation . Mechanical feedback associated with sarcomere shortening also controls the transition from the strong binding state to the weak binding state , thereby determining the duration of state . The mechanical feedback, which is indicated as a unidirectional rate constant kvel in FIGURE , occurs as a result of strain imposed on active cross bridges with shortening, a process known as shorteninginduced deactivation , , . Thus the balance of the intensity of the cooperative mechanisms, which promote the transition to state , and the mechanical feedback, which promotes dissipation of state , determine the population of cross bridges in state . Therefore, these mechanisms are likely to be important determinants of the time to the end of systole. Another more controversial possibility to increase crossbridge availability permitting feedback would be to allow individual cross bridges to interact with the thin filament multiple times during activation. The crossbridge cycle described by FIGURE assumes cross bridges driving cardiac pump function are tightly coupled to ATP hydrolysis i.e., one ATP per crossbridge cycle. However, questions remain as to the validity of this assertion. Evidence for a more loosely coupled system comes from observations by the Yanagida laboratory and Lombardi et al. that a single cross bridge can move actin many times the length of a single crossbridge swing on an individual ATP and that cross bridges can reprime following a power stroke without binding additional ATP, respectively. In agreement, based on experimental data concerning lengthtension area analogous to pressurevolume area vs. oxygen consumption, Taylor et al. concluded the cross bridgetoATP ratio may be variable with tightly coupled usage at high loads becoming more loosely coupled at low loads where muscle may shorten reviewed in Ref. . Downloaded from physiologyonline.physiology.org on May , A Dominant Role of Processes Involving Cardiac Molecular Motors in Left Ventricular Ejection and Isovolumic Relaxation Ultimately, the reactions of molecular motors in the left ventricle FIGURE are responsible for the ejection of blood into the peripheral circulation. During a beat of the left ventricle, pressure rises for a time with no change in ventricular volume and limited internal shortening of the sarcomeres. During this phase, cross bridges are recruited into action as Ca rises in the sarcomeric space. When the aortic valve opens, ejection begins and the sarcomeres shorten. In this phase, cross bridges impel the thin filaments toward the center of the sarcomere. Shortening imposes a strain on reacting cross bridges and alters the kinetics of the actinmyosin reaction. As systole progresses and blood flows to the periphery, left ventricle pressure falls, the valve closes, pressure falls with no change in ventricular volume, and the strain dependence of actin crossbridge kinetics is greatly relieved. Unfortunately, much of our understanding of the cellular mechanisms governing these processes such as the dynamics of excitation contraction coupling and relaxation is based on determinations of intracellular Ca and mechanics with myocytes shortening against zero loads or not PHYSIOLOGY Volume April www.physiologyonline.org REVIEWS shortening at all. In the following, we expand governance of these processes to include prominent, intrinsic sarcomeric regulation of these processes and alterations occurring with changes in load. ejection of the blood added to the ventricle during diastole. FIGURE depicts the time course of Ca bound to cTnC in a region of the A band of sarcomeres at various time points during pressure changes during a beat of the left ventricle. The figure illustrates our perception of the state of the Aband region at various time points during the beat. Estimation of Ca binding to the thin filaments is based on a computational model of Burkoff , which is in general agreement with experimental findings and other models of transitions in thinfilament RUs during left ventricular pressure development in a beat of the heart . These models are driven by experimental determinations of the transient change in Ca , and by determinations of kinetics and steadystate binding of Ca to Tn in myofilaments , . The estimate is Differences in kinetics of sarcomericbound Ca and pressure during a heart beat A major challenge in the investigation of molecular control mechanisms in regulation of the heart beat is how to connect the action of the cardiac molecular motors to global ventricular function. These actions include state transitions leading to development of force and shortening, promotion of the activated state of thin filaments, response to the prevailing preload and afterload, and the relative amounts of Cabound to cTnC related to contractility that ensures efficient Downloaded from physiologyonline.physiology.org on May , FIGURE . Relation between Ca bound to cardiac thin filaments CaTnTmActin and left ventricular pressure LVP in a beat of the heart Note that Ca bound to the thin filament wanes at a time when ejection is still underway. See text for further description of intrinsic sarcomeric mechanism sustaining ejection independent of bound Ca and determining rate of isovolumic relaxation. Computation of bound Ca based on Burkhoff . PHYSIOLOGY Volume April www.physiologyonline.org REVIEWS also based on studies by Peterson et al. , who applied a mechanical assay to determine the time course of the amounts of Ca bound to cTnC, and by Ishikawa et al. , who used a quickrelease protocol and intracellular aequorin to determine cTnCbound Ca. These studies both demonstrated that the fall in thinfilamentbound Ca precedes the fall in force in an isometric twitch of heart muscle. A significant outcome of these measurements and models is that they indicate that, during a heartbeat, the time course of Ca bound to the thinfilament cTnC is nearly over at a time when ejection is ongoing and isovolumic relaxation has not yet begun. We interpret this difference in time course of thinfilament Ca binding and pressure to mean that much of ejection and relaxation of the ventricle depends on molecular processes intrinsic to the sarcomere. These intrinsic molecular processes involve the following significant actions of the cardiac molecular motors activation of the thin filaments by cooperative mechanisms sustaining thinfilament activation despite a fall in thinfilamentbound Ca, sensing the sarcomere length preload in a mechanism explaining the FrankStarling law, sensing the load in a mechanism related to the inverse relationship between force and velocity, and relaxation kinetics related to rates of crossbridge detachment and intersarcomere dynamics as described by Stehle et al. . sarcomeres provides the cellular mechanism for the FrankStarling law. Yet the theory that length dependence of activation is well correlated with changes in interfilament spacing has not stood the test of direct determination of the interfilament spacing by Xray diffraction , . ...the time course of Ca bound to the thinfilament cTnC is nearly over at a time when ejection is ongoing and isovolumic relaxation has not yet begun. Processes intrinsic to the sarcomere control systolic mechanics and relaxation Consideration of the change in the state of the Aband sarcomeric proteins during the transition from diastole to systole and the return to diastole during a heart beat serves to describe the interplay between control mechanisms extrinsic such as membranedependent regulation of Ca fluxes and mechanisms intrinsic to the sarcomere. In the diastolic state, cross bridges are either blocked from reacting with actin or in a weak, nonforcegenerating state FIGURE . The molecular motors of the heart are not completely passive in diastole in that they are likely to sense the preload. There is evidence that the state of stretch of the myocardium at the end of diastole is transmitted to the cross bridges by titin, which is responsible for the passive force of the myocyte . Preload determines the strain on titin, and it is plausible although not fully documented that the net effect of the longitudinal and radial strain on titin alters interfilament spacing or provides a signal acting through a titinMyBPCcrossbridge interaction by which the molecular motors sense sarcomere length . In general, it has been thought that the motors sense sarcomere length via a lengthdependent change in interfilament spacing, which in effect alters the local concentration of cross bridges at the actin binding sites and thereby alters the myofilament response to Ca , , . This lengthdependent activation of the With release of Ca into the sarcomeric space, Ca binds to cTnC, and systole begins. The transient change of intracellular Ca in the sarcomeric space, as detected by intracellular fluorescent probes, demonstrates only of the total cellular Ca that moves from the extracellular space and sarcoplasmic reticulum SR and back during a heart beat . Thus the bulk of these Ca ions is bound to buffers including TnC and other regulatory Cabinding proteins such as calmodulin . With the rise in cTnCbound Ca, which is shown in FIGURE , cross bridges make the transition from the blocked or weak binding state to a strong forcegenerating state. A reasonable estimate is that of available cross bridges are recruited into the systolic state during resting levels of cardiac output . The reactions of these cross bridges generate the wall tension responsible for the rising phase of left ventricular pressure shortening is limited until sufficient pressure is generated to open the aortic valve. Removal of Ca from the sarcoplasm by the SR pump and the Na/Ca exchanger sets into motion a process whereby Ca is released from cTnC, and this is in part responsible for the decay in Ca bound to the thin filaments. However, as illustrated in FIGURE , this fall in thinfilament Ca binding precedes the fall in left ventricular pressure, thus indicating that the actin crossbridge reactions are sustained even in the face of a decline in Cadependent activation. Moreover, at the time the aortic valve opens, cooperative mechanisms in which thin filament RUs remain active without Ca bound sustain ejection FIGURE . Computational models indicate that this state occurs by cooperative mechanisms within an RU in which crossbridge binding to the thin filament increases the affinity of cTnC for Ca step in FIGURE and by nearneighbor cooperative mechanisms acting longitudinally along the thin filament , . As ejection proceeds against the afterload, cross bridges enter into a new state in which the strain imposed by shortening promotes release of ADP from the cross bridges, an increase in ATP turnover, and an increase in crossbridge detachment rate. The effect of Downloaded from physiologyonline.physiology.org on May , PHYSIOLOGY Volume April www.physiologyonline.org REVIEWS strain on cross bridges is well accepted to affect nucleotide binding. For example, in slow skeletal muscle, ADP release is sensitive to the load the lighter the load, the greater the shortening velocity, the faster the release of ADP, and the faster the ATP turnover . This strain dependence of crossbridge kinetics is the basis for the Fenn effect. This mechanical feedback thus promotes the transition of cross bridges from strong to weak binding states step in FIGURE and lowers the affinity of cTnC for Ca. As a result, rate of loss of bound Ca is enhanced. Thus systolic mechanics reflect a balance between cooperative activation of thin filaments and shorteninginduced deactivation . It is evident that the dissipation of the cooperative activation is relatively slow. In shortening from a long to a short length, Chandra and Campbell suggest that the sarcomeres remember the higher force attained at the longer length and shortening ejection is prolonged in comparison to the situation with no cooperative mechanisms. The kinetics of the crossbridge cycle and the relative time the cross bridges are strongly bound, especially the rate of detachment of cross bridges, is also an important determinant of the time in ejection and the isovolumic relaxation rate. Mechanisms at the level of the sarcomere that affect relaxation include the dissipation of the cooperative activation of the thin filament and forward detachment of cross bridges as ATP binding to cross bridges reestablishes the actinmyosinADPPi weak binding state state in FIGURE . A third mechanism is a straindependent reversal of the power stroke transition from the actinmyosinADP state to the actinmyosinADPPi state a transition from state to state , as illustrated in FIGURE . In the case of myofibril preparations, relaxation is accelerated by small stretches and by increased Pi concentration . These common effects have been interpreted by Poggesi et al. to indicate that, in relaxation, both Pi binding to cross bridges and altered crossbridge strain during relaxation may result in reversal of the power stroke. If a significant number of the cross bridges undergo this reversal of the power stroke, then a significant potential outcome is that weak binding cross bridges are reestablished without splitting ATP and ready to engage in the crossbridge cycle in the next beat. Direct tests of the relative significance of processes extrinsic to the sarcomere Ca uptake by the SR and these processes intrinsic to the sarcomere indicate that the intrinsic processes can be rate limiting. For example, in the experiments of Peterson et al., the derivative curve of bound Ca fell to low levels, whereas force remained high during the onset of relaxation in an isometric twitch. This result indicates that factors other than the velocity of SR Ca uptake are rate limiting in loaded ejections with shortening. Sys and Brutsaert reached the same conclusion using a different experimental approach. On the other hand, when Peterson et al. used ryanodine to slow Ca uptake by SR, the fall in force and cTnCbound Ca occurred in parallel. Thus, when SR Ca uptake is slowed down as in heart failure , the role of processes intrinsic to the sarcomeres becomes relatively blunted. Control of Cardiac Molecular Motors by Modulation of Thick and ThinFilament Regulatory Proteins Phosphorylation of thin and thickfilament regulatory proteins that modulate the actincrossbridge reaction also affect duration of ejection and relaxation. Although multiple sarcomeric proteins are modified by phosphorylation reviewed in Refs. , , we focus here on MyBPC and cTnI inasmuch as the state of these proteins has been reported to affect systolic mechanics. Both proteins are phosphorylated by protein kinase A at sites unique to the cardiac variants. In the case of MyBPC, compared with controls, mouse hearts lacking cMyBPC demonstrate a significantly abbreviated time course of systolic elastance . There is little change in the early phase of systole, but hearts lacking MyBPC relax prematurely. Sarcomeres lacking MyBPC also have faster unloaded shortening velocity than controls . Importantly, PKAdependent phosphorylation of MyBPC, which occurs at a site that interacts with myosin S, mimics the effects of its ablation . Thus it is apparent and likely that the state of MyBPC modifies the transmission of force across the sarcomere as well as shorteninginduced deactivation. This finding may be of significance regarding the pathology of mutations in MyBPC, which are a common cause of familial cardiomyopathy . Among TnI variants, cTnI is unique in having an NHterminal extension of amino acids that contain PKAdependent phosphorylation sites. Phosphorylation of these sites appears pivotal in the positive inotropic response to adrenergic stimulation and to changes in frequency . However, the demonstration of both of these effects is most evident in auxotonically loaded, ejecting hearts and much less evident in isovolumic hearts, isometric muscle preparations, or unloaded isolated myocytes. The increases in ejection indexes, such as stroke work and the endsystolic pressurevolume relation, are significantly blunted in hearts expressing slow skeletal TnI which lacks the PKA sites in place of cTnI . However, myocytes from these hearts or isovolumic hearts demonstrated nearly the same inotropic responses to adrenergic stimulation as the controls. Phosphorylation of cTnI has also been reported to increase unloaded shortening velocity and power generation by isolated, skinned cardiac myocytes and to enhance the effect of sarcomere length on forceCa relation . Taken together, these results indi Downloaded from physiologyonline.physiology.org on May , PHYSIOLOGY Volume April www.physiologyonline.org REVIEWS cate a significant involvement of the cTnI phosphorylation in cardiac systolic mechanics and relaxation in response to adrenergic stimulation by its effects on the cooperative activation and mechanical feedback. Hearts of transgenic mice TGcTnIDD expressing cTnI, in which the PKAtargeted Ser are mutated to Asp as a phosphorylation mimetic, also show responses to increases in frequency, indicating an effect of cTnI phosphorylation on ratedependent increases in systolic function . Moreover, there was a prolonged relaxation associated with increased afterload in nontransgenic control hearts beating in situ when compared to the TGcTnIDD hearts. This difference was not evident when the hearts were treated with isoproterenol. As with the studies on the TGssTnI hearts, frequencydependent responses in isometric trabeculae from the TGcTnIDD hearts did not demonstrate differences from controls . These studies reinforce the role of cTnI phosphorylation on systolic function and relaxation kinetics and also indicate that the mechanism is revealed when cross bridges function against a load as in the ejecting ventricles. It has been reported that that there is a diminished TnI phosphorylation in that, which is likely to be an important mechanism in the blunted forcefrequency relation of failing human hearts. References . Bonne G, Carrier L, Bercovici J, Cruaud C, Richard P, Hainque B, Gautel M, Labeit S, James M, Beckman J, Weissenbach J, Vosberg HP, Fiszman M, Komajda M, Schwartz K. Cardiac myosin binding proteinC gene splice acceptor site mutation is associated with familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Nat Genet , . Burkhoff D. Explaining load dependence of ventricular contractile properties with a model of excitationcontraction coupling. J Mol Cell Cardiol , . Campbell KB, Chandra M. Functions of Stretch Activation in Heart Muscle. J Gen Physiol , . De Tombe PP, ter Keurs EDJ. An internal viscous element limits unloaded velocity of sarcomere shortening in rat cardiac trabeculae. J Physiol , . Fitzsimmons DP, Patel JR, Moss RL. Role of myosin heavy chain composition in kinetics of force development and relaxation in rat myocardium. J Physiol , . Fitzsimons DP, Moss RL. Strong binding of myosin modulates lengthdependent Ca activation of rat ventricular myocytes. Circ Res , . Fitzsimons DP, Patel JR, Moss RL. Crossbridge interaction kinetics in rat myocardium are accelerated by strong binding of myosin to the thin filament. J Physiol , . . .. . . . Downloaded from physiologyonline.physiology.org on May , . Fukuda N, Granzier HL. Titin/connectinbased modulation of the FrankStarling mechanism of the heart. J Muscle Res Cell Motil , . Gordon AM, Homsher E, Regnier M. Regulation of Contraction in Striated Muscle. Physiol Rev , . . . Gordon AM, Ridgway EB. Crossbridges affect both TnC structure and calcium affinity in muscle fibers. Adv Exp Med Biol discussion , . . Hamilton N, Ianuzzo CD. Contractile and calcium regulating capacities of myocardia of different sized mammals scale with resting heart rate. Mol Cell Biochem , . . Harris DE, Work SS, Wright RK, Alpert NR, Warshaw DM. Smooth, cardiac, and skeletal muscle myosin force and motion generation assessed by crossbridge mechanical interactions in vitro. J Muscle Res Cell Motil , . . Herron TJ, Korte FS, McDonald KS. Loaded shortening and power output in cardiac myocytes are dependent on myosin heavy chain isoform expression. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol HH, . . Herron TJ, Korte FS, McDonald KS. Power output is increased after phosphorylation of myofibrillar proteins in rat skinned cardiac myocytes. Circ Res , . . Hinken AC, McDonald KS. Inorganic phosphate speeds loading shortening and increases power output in rat skinned cardiac myocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol CC, . . Hoh JFY, McGrath PA, Hale PT. Electrophoretic analysis of multiple forms of rat cardiac myosin effects of hypophysectomy and thyroxine replacement. J Mol Cell Cardiol , . . Holubarsch C, Goulette RP, Litten RZ, Martin BJ, Mulieri LA, Alpert NR. The economy of isometric force development, myosin isozyme pattern and myofibrillar ATPase activity in normal and hypothyroid rat myocardium. Circ Res , . . Homsher E, Lacktis J, Regnier M. Straindependent modulation of phosphate transients in rabbit skeletal muscle fibers. Biophys J , . . Ishikawa T, OUchi J, Mochizuki S, Kurihara S. Evaluation of the crossbridgedependent change in the Ca affinity of troponin C in aequorininjected ferret ventriculr muscles. Cell Calcium , . . Iwamoto I. Thin filament cooperativity as a major determinant of shortening velocity in skeletal muscle fibers. Biophys J , . . Kass DA, Solaro RJ. Mechanisms and use of calciumsensitizing agents in the failing heart. Circulation , . Novel Pharmaceutical Therapies Targeting Molecular Motors Translation of the detailed understanding of sarcomeric regulation to therapeutics is an important research objective, and there is evidence that pharmacological modification of molecular motors may be useful as a therapeutic approach for heart failure. One aim has been the discovery of small molecules that directly modify sarcomeric proteins and improve cardiac function. Early phases of the search for such compounds that enhance myofilament sensitivity to Ca targeted thinfilament proteins. Examples of these agents are levosimendan and EMD , which bind to cTnC, and pimobendan, which promotes Ca binding to cTnC. These agents improves systolic function in animal models of heart failure as reviewed in Ref. , and levosimendan and pimobendan have progressed into clinical use. More recently, there has been a search for agents directly affecting the molecular motors of the heart. Although further studies are required to establish the value of these agents in human therapeutic application, the initial data are promising . It is apparent that modification of the myosin by these agents prolongs systolic ejection. This indicates that these agents alter the balance of cooperative mechanisms and shortening induced deactivation such that systolic mechanics are enhanced. Whether modification of troponin and/or MyBPC by drugs may also affect this balance appears possible but has not been investigated explicitly. PHYSIOLOGY Volume April www.physiologyonline.org REVIEWS . Kentish JC, McCloskey DT, Layland J, Palmer S, Leiden JM, Martin AF, Solaro RJ. Phosphorylation of troponin I by protein kinase A accelerates relaxation and cossbridge cycle kinetics in mouse ventricular muscle. Circ Res , . . Kitamura K, Tokunaga M, Iwane AH, Yanagida T. A single myosin head moves along an actin filament with regular steps of . nanometres. Nature , . . Kobayashi T, Solaro RJ. Calcium, thin filaments, and the intregrative biology of cardiac contractility. Annu Rev Physiol , . . Konhilas JP, Irving TC, de Tombe PP. FrankStarling law of the heart and the cellular mechanisms of lengthdependent activation. Pflgers Arch , . . Konhilas JP, Irving TC, Wolska BM, Jweied EE, Martin AF, Solaro RJ, de Tombe PP. Troponin I in the murine myocardium influence on lengthdependent activation and interfilament spacing. J Physiol , . . Korte FS, McDonald KS, Harris SP, Moss RL. Loaded shortening, power output, and rate of force redevelopment are increased with knockout of cardiac myosin binding proteinC. Circ Res , . . Kunst G, Kress KR, Gruen M, Uttenweiler D, Gautel M, Fink RHA. Myosin binding protein C, a phosphorylationdependent force regulator in muscle that controls the attachment of myosin heads by its interaction with myosin S. Circ Res , . . Landesberg A. Endsystolic pressurevolume relationship and intracellular control of contraction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol HH, . . Lehman W, Craig R, Vibert P. Cainduced tropomyosin movement in Limulus thin filaments revealed by threedimensional reconstruction. Nature , . . Loiselle DS, Wendt IR, Hoh JFY. Energetic consequences of thyroidmodulated shifts in ventricular isomyosin distribution in the rat. J Muscle Res Cell Motil , . . Lombardi V, Piazzesi G, Linari M. Rapid regeneration of the actinmyosin power stroke in contracting muscle. Nature , . . Lompre AM, NadalGinard B, Mahdavi V. Expression of the cardiac ventricular alpha and betamyosin heavy chain genes is developmentally and hormonally regulated. J Biol Chem , . . Malik F, Teerlink JR, Escandon RD, Clark CP, Wolff AA. The selective cardiac myosin activator, CK, a calciumindependent inotrope, increases left ventricular systolic function by increasing ejection time rather than the velocity of contraction Abstract. Circulation II, . . Martin AF, Pagani ED, Solaro RJ. Thyroxineinduced redistribution of isoenzymes of rabbit ventricular myosin. Circ Res , . . Martyn DA, Rondinone JF, Huntsman LL. Myocardial segment velocity at a low load time, length, and calcium dependence. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol HH, . . McDonald KS, Herron TJ. It takes heart to win what makes the heart powerful News Physiol Sci , . . McDonald KS, Moss RL. Osmotic compression of single cardiac myocytes reverses the reduction in Ca sensitivity of tension observed at short sarcomere length. Circ Res , . . McDonald KS, Moss RL. Strongly binding myosin crossbridges regulate loaded shortening and power output in cardiac myocytes. Circ Res , . . Moss RL, Razumova M, Fitzsimons DP. Myosin crossbridge activation of cardiac thin filaments implications for myocardial function in health and disease. Circ Res , . . Pagani ED, Julian FJ. Rabbit papillary muscle myosin isozymes and the velocity of muscle shortening. Circ Res , . . Palmer BM, Georgakopoulos D, Janssen PM, Wang Y, Alpert NR, Belardi DF, Harris SP, Moss RL, Burgon PG, Seidman CE, Seidman JG, Maughan DW, Kass DA. Role of cardiac myosin binding protein C in sustaining left ventricular systolic stiffening. Circ Res , . . Pan BS, Solaro RJ. Calciumbinding properties of troponin C in detergentskinned heart muscle fibers. J Biol Chem , . . Peterson JN, Hunter WC, Berman MR. Estimated time course of Ca bound to troponin C during relaxation in isolated cardiac muscle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol HH, . . Piacentino V, III, Weber CR, Chen X, WeisserThomas J, Margulies KB, Bers DM, Houser SR. Cellular basis of abnormal calcium transients of failing human ventricular myocytes. Circ Res , . . Poggesi C, Tesi C, Stehle R. Sarcomeric determinants of striated muscle relaxation kinetics. Pflgers Arch , . . Pope B, Hoh JFY, Weeds A. The ATPase activities of rat cardiac myosin isoenzymes. FEBS Lett , . . Rasumova MV, Bukatina AE, Campbell KB. Different myofilament nearestneighbor interactions have distinctive effects on contractile behavior. Biophys J , . . Robertson SP, Johnson JD, Potter JD. The timecourse of Caexchange with calmodulin, troponin, parvablumin, and myosin in response to transient increases in Ca. Biophys J , . . Rundell VL, Geenen DL, Buttrick PM, de Tombe PP. Depressed cardiac tension cost in experimental diabetes is due to altered myosin heavy chain isoform expression. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol HH, . . Shirakawa I, Chaen S, Bagshaw CR, Sugi H. Measurement of nucleotide exchange rate constants in single rabbit soleus myofibrils during shortening and lengthening using a fluorescent ATP analog. Biophys J , . . Sipido KR, Wier WG. Flux of Ca across the sarcoplasmic reticulum of guineapig cardiac cells during excitationcontraction coupling. J Physiol , . . Solaro RJ. Modulation of Cardiac Myofilament Activity by Protein Phosphorylation. New York Oxford Univ. Press, . . Stelzer JE, Moss RL. Contributions of stretch activation to lengthdependent contraction in murine myocardium. J Gen Physiol , . . Stelzer JE, Patel JR, Moss RL. Protein kinase Amediated acceleration of the stretch activation response in murine skinned myocardium is eliminated by ablation of cMyBPC. Circ Res , . . Stephenson GM, Stephenson DG. Endongenous MLC phosphorylation and Caactivated force in mechanically skinned skeletal muscle fibres of the rat. Pflgers Arch , . . Suga H. Mechanoenergetic estimation of multiple crossbridge steps per ATP in a beating heart. Jpn J Physiol , . . Sugiura S, Kobayakawa N, Fujita H, Yamashita H, Momomura S, Chaen S, Omata M, Sugi H. Comparison of unitary displacements and forces between cardiac myosin isoforms by the optical trap technique molecular basis for cardiac adaptation. Circ Res , . . Sweeney HL, Stull JT. Phosphorylation of myosin in permeabilized mammalian cardiac and skeletal muscle cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol CC, . . Sys SU, Brutsaert DL. Determinants of force decline during relaxation in isolated cardiac muscle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol HH, . . Takimoto E, Soergel DG, Janssen PM, Stull LB, Kass DA, Murphy AM. Frequency and afterloaddependent cardiac modulation in vivo by troponin I with constitutively active protein kinase A phosphorylation sites. Circ Res , . . Taylor TW, Goto Y, Suga H. Variable crossbridge cyclingATP coupling accounts for cardiac mechanoenergetics. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol HH, . . Tobacman LS. Thin filamentmediated regulation of cardiac contraction. Annu Rev Physiol , . . Trafford AW, Diaz ME, Eisner DA. A novel, rapid and reversible method to measure Ca buffering and timecourse of total sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca content in cardiac ventricular myocytes. Pflgers Arch , . . Trybus KM. Role of myosin light chains. J Muscle Res Cell Motil , . . VanBuren P, Harris DE, Alpert NR, Warshaw DM. Cardiac V and V myosins differ in their hydrolytic and mechanical activities in vitro. Circ Res , . . Winegrad S, Weisberg A. Isozyme specific modification of myosin ATPase by cAMP in rat heart. Circ Res , . . Xu C, Craig R, Tobacman LS, Horowitz R, Lehman W. Tropomyosin positions in regulated thin filaments revealed by cryoelectron microscophy. Biophys J , . . Zhao Y, Kawai M. Kinetic and thermodynamic studies of the crossbridge cycle in rabbit psoas muscle fibers. Biophys J , . Downloaded from physiologyonline.physiology.org on May , PHYSIOLOGY Volume April www.physiologyonline.org