* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Case Study: Africa - Red Cross Red Crescent Climate Centre

Climate change denial wikipedia , lookup

Climate resilience wikipedia , lookup

Climate engineering wikipedia , lookup

Solar radiation management wikipedia , lookup

Climate change adaptation wikipedia , lookup

Climate governance wikipedia , lookup

Attribution of recent climate change wikipedia , lookup

Citizens' Climate Lobby wikipedia , lookup

Media coverage of global warming wikipedia , lookup

Climate change in Tuvalu wikipedia , lookup

Scientific opinion on climate change wikipedia , lookup

Climate change in Saskatchewan wikipedia , lookup

Climate change in Australia wikipedia , lookup

Global Energy and Water Cycle Experiment wikipedia , lookup

Public opinion on global warming wikipedia , lookup

IPCC Fourth Assessment Report wikipedia , lookup

Climate change in the United States wikipedia , lookup

Surveys of scientists' views on climate change wikipedia , lookup

Climate change and poverty wikipedia , lookup

Climate change and agriculture wikipedia , lookup

Effects of global warming on human health wikipedia , lookup

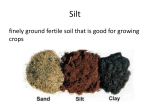

Case Study: Africa | Red Cross/Red Crescent Climate Guide | 71 70 | Red Cross/Red Crescent Climate Guide | Case Study: Africa The yield from rain-fed agriculture could be reduced by up to 50% by 2020, according to scientists on the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Many parts of Africa are already considered “water stressed” – something that will be exacerbated by climate change. Any significant rise in temperature could also seriously affect cash crops such as tea or coffee. Arid and semi-arid areas all over Africa are becoming yet drier. On average the continent is 0.5 °C warmer than it was 100 years ago, in some parts even more. Migration is another outcome of climate change as people move away from drought-prone areas and work as labourers on other farms to earn money to buy food, increasing pressure on particular parts of the continent. Case Study: Africa Ethiopia Scorched landscapes, withered crops, dried-up rivers and lakes; or the opposite – devastating floods; dying livestock, hungry people. This could be the picture we face in Africa in a decade unless we manage climate risks better. Communities are vulnerable to unfamiliar hazards and cannot cope with even minor shocks – leading to a constant rise in the numbers of people needing humanitarian assistance. The average number of food emergencies in Africa per year has almost tripled since the mid-1980s, and in the last year alone 25 million people faced a food crisis. New research suggests that the vulnerability to the climate-change threat is in Africa greater than in many parts of the world. And the changes won’t be limited to a rising average temperature and changing rainfall patterns. Droughts and floods are happening with increasing severity and frequency, accompanied by diseases such as diarrhoea. Malaria is also making an appearance at altitudes that previously had no mosquitoes, such as in the mid-highlands in Ethiopia. Rift Valley Fever has reappeared. Africa, with its resources already overstretched, has little capacity to deal with further disasters from climate change. Around 90% of people depend on agriculture for their livelihoods – many are subsistence farmers who only grow enough food to feed themselves and their families. Any decrease or change in rainfall patterns could mean crop failure and consequently serious food shortages or even famine. Changing weather patterns in recent years are having a detrimental impact on food security; farmers are finding they can no longer plant or harvest their crops as they used to for centuries as rainfall is late or erratic. Agricultural production will be severely impacted by climate change – the area suitable for agriculture, growing seasons and yield are all expected to decrease. This would further adversely affect food security and exacerbate malnutrition in some countries. Divided by the East African Rift Valley into highlands and lowlands, Ethiopia has an extraordinarily diverse climate, from the cool and rainy Dega highlands to the Danakil depression – one of the hottest, driest places on Earth. The economy is based on agriculture, which accounts for half GDP, 60 per cent of exports and 80 per cent of total employment. But only 1 per cent of farmed land is irrigated and drought can throw the whole country into crisis and food shortage. According to Abebe Tadege, head of research at the national meteorological office in Addis Ababa: “There have been signs of climate change in Ethiopia since 2000, and even before. Tropical Africa is a hotspot for precipitation changes. I am very worried. What is the impact on crops, on tef [the traditional staple], tea, coffee, livestock?” With five major droughts in two decades, many families have not had time to recover and hundreds of thousands of people live on the brink of survival every year. In 2000–3, 46% of the population were malnourished, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization. Meanwhile 2006 saw some of the worst floods in Ethiopia’s history, displacing people all over the country. Flash floods in Dire Dawa, the second largest city after Addis Ababa, killed nearly 250 people and displaced thousands. More than 400 people died during outbreaks of acute watery diarrhoea in 2006. Fadis, in the east, has been badly hit by drought. Many farmers have suffered from poor harvests year after year due to erratic rainfall. In recent years the rains have failed completely. Yusuf Idris, a village elder, has lived in the area for 40 years and his family and community are regularly dependent on relief food. The rains have failed consistently for the last few years and he cannot plant his crops. “When there is a little rain, we can plant sorghum and maize but we don’t produce much,” he says. The nearby River Boco, which used to be one of the main sources for irrigation in the area dried up several years ago, partly because of the lack of rainfall. Yusuf remembers orange and lemon groves beside the river. He reports that many people in his community migrate every year because of drought, and scarcity of food and water. Malaria A few kilometres away near the town of Harar, Lake Halamaya also dried up several years ago, partly because of the scarcity of rainfall in the region. Lake Halamaya, about five kilometres long, was the main source of water for Harar and the surrounding communities and provided income for fishermen. Fatiya Abatish Jacob is a local trader who lived near the lake for 14 years: “I used to get my drinking water from the lake, now I have to walk eight kilometres to get it. Also there were many vegetables farmers round here using the water for irrigation and we used to get fish. Now there are no fish around here and vegetables are more expensive.” Case Study: Africa | Red Cross/Red Crescent Climate Guide | 73 72 | Red Cross/Red Crescent Climate Guide | Case Study: Africa And while there was drought in Harar area to the south there were bad floods in 2006 in west Shoa, where 3,000 people were displaced. “Such heavy flooding hasn’t happened for 40 years,” says Tiringo Engdawork, Ethiopian Red Cross Society (ERCS) branch secretary. “It destroyed houses, crops and cattle.” Local malaria rates have shot up. Acute Watery Diarrhoea cases were recorded for the first time in ten years. And there is clearly interaction between malnutrition, malaria and HIV/AIDS. ERCS disaster preparedness emphasizes clean water and tree planting for wood, fruit and terracing. Gabriel Aebachew, head of organizational development, believes that they have to now “create awareness of climate change, collect data and train volunteers” at branch level. Despite a decade of rapid economic growth, poverty remains widespread in Rwanda. Known as the “land of a thousand hills”, Rwanda is a small landlocked country surrounded by Burundi, Tanzania, Uganda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. But despite its size, it has very diverse ecosystems. According to relief officer Geude Beyenne: “We have volunteers trained in disaster preparedness activities in every part of Ethiopia. We started two years ago because we realise we are affected by natural calamities more frequently. We are trying to prepare relief materials such as blankets and jerrycans and store them in various regions. The policy now is that 10% of branch income will go to supplies for preparedness activities.” Rwanda forms part of the Great East African Plateau, which rises from the lowlands in the west that are characterized by swamps and lakes to the highlands of the east. This divides the country between the Nile basin and the Congo basin. The climate is moderate and tropical, with a short dry season from January to February and a long dry season from June to September. The ERCS has also placed considerable importance on the need to conserve water. Rain “harvesting” is an efficient way of collecting clean water during the rainy period and it can last several weeks or months. “In Moyale, for example, in the south, there is no river and so rainwater harvesting is important,” Geude Beyenne explains. “Water is key, especially in disaster preparedness. Some people in the south might only use a litre a week.” More than 50 rainwater harvesting tanks, on roofs and underground, have been built in the last two or three years. The ERCS also has a programme of communitybased health care for awareness-raising and education, but this will have to be scaled up in the light of climate change. Malaria, typhoid, cholera and diarrhoea are all diseases that spread more rapidly during times of hardship. Diseases that were considered to have been eradicated are also making a reappearance. In 2006 Rwanda The agricultural sector is central to Rwandan environment. It dominates the economy in terms of contribution to the GDP and it also accounts for over 90% of employment. Agricultural exports represent over 70% of the total; coffee and tea are the two main export crops. Climate change could have serious consequences for agricultural production. In 2006, there were a number of deaths as a result of heavy rain and floods, and crops and livestock were destroyed. Patricia Hajabakiga, the environment minister, said this affected the national budget as money intended for economic development was used for emergency measures such as buying food relief. At the same time water levels have gone down and hydroelectric stations, particularly in Ntaruka and Mukungwa, have been affected. Electricity generation has declined and there has been an energy crisis in the last few years; to produce electricity the government has had to buy generators costing millions of dollars. This had an impact on the population – with the price of electricity tripling. Parts of Rwanda have been hit by persistent drought over the last few years, rainfall patterns have been erratic with the result that, again, farmers are confused as to when to plant and harvest. Musoni Didace, director of the country’s meteorological service says climate change is “clearly visible” from the rise in minimum temperatures in the last 30 years of up to two degrees. Migration Bugusera, in southern Rwanda, is an area that has persistently been hit by drought and here around 40% of people lack secure sources of food. Many farmers in this area have suffered from bad harvests due to late or erratic rainfall. Indeed 2005, was the hottest year for many years in Rwanda. Temperatures in the capital, Kigali, soared to 35 °C. Higher temperatures also mean the spread of diseases such as malaria, already the principal cause of morbidity and mortality in every province. Mary Jane Nzabamwita is a farmer in Gashora with five children to feed. Since 1998 rain has become unpredictable. “We think it will rain, then it doesn’t rain and then we lose our harvest,” she explains. Mary Jane grows sorghum, beans, sweet potatoes and vegetables, some of which are sold at the market but last year her harvest was down by half. The interaction between diseases is also of concern: someone with malaria, for example, will be more prone to catching HIV, and vice versa. Malnutrition also means diseases spread more rapidly. It is a vicious circle. And diseases thought to have died out, like cholera, are reappearing. New cholera cases were recorded for the first time in Kigali in 2006 and in the north-east in 2007. She just managed to save enough money to send her children to school (the children get food from the World Food Programme at school), but she cannot afford to pay for health insurance fees for the whole family. The family now has to drink water from the nearby swamps and continually suffer from diarrhoea and malaria. “I feel like I am going backwards,” she says. “The children are not doing so well. When you see a child of ten, you think he is five.” A Rwandan Red Cross Society (RRCS) volunteer in Bugusera explains that you can now see more erratic climate patterns and drought is making people migrate to other areas of Rwanda where they can work. People might also go to a nearby town, earn some cash there by petty trade and buy some food to sell in their own villages. Many families are separated. Mimi and Josephine are looking after their children and their farms while their husbands have gone elsewhere to earn some cash. This year their maize crops have failed due to lack of rainfall and they are still hoping for rain for their bean harvest. If they fail or come late, they do not know how they are going to get their food. Migration became such as serious problem that almost 80% of the people in the area left their farms to look for work in other regions between 2003–5. However, the local government has tried to stockpile maize, sorghum and beans and migration has now decreased, according to Viateur Ndavisabye, executive secretary of the Gashora regional government. “Climate change is a big problem,” says Apollinaire Karamaga, RRCS secretary general. “We need to train volunteers with basic skills, like being able to advise farmers when to sow seeds, dig the swamp, and so on. We need to help them think, ‘What can I do according to my realities to cope?’” According to Marie-Antoinette Uwimana, RRCS head of programmes: “The government has started talking about climate change this year, and as we are a member of the disaster management task force, we discussed this with them.” There is now a realisation that disaster response is no longer enough and that risk reduction is important and has to be scaled up. “The impacts from climate change are there and have been problems in the last years,” according to Eric Njibwami, head of volunteers. “The eastern and southern regions suffer from lack of food because 74 | Red Cross/Red Crescent Climate Guide | Case Study: Africa of the long season without rain.” The result is that communities can no longer plan harvests or planting because of erratic rains. The RRCS tries to address this by informing people when they are going to have a drought, getting weather information and warning people to keep a stock of food. But in the long term, says Eric Njibwami, people have to “diversify through business activities or generating other incomes”. A major problem is that farmers are very traditional and hesitant to change, says Karamaga. “We may need to change our crops or diets in the future, but people change only very slowly.” He believes it’s important to train volunteers to train farmers to move away from their traditional methods of producing crops, which may not be the most efficient in today’s circumstances. Clearly water management and environmental protection of land is going to be key. Due to population pressure much of Rwanda has been deforested – with resulting soil degradation and erosion which worsens the impact of drought. Almost 90% of the population use wood as cooking fuel. Mobilising the community to plant trees is, therefore, an important objective for the Rwanda Red Cross. The eventual aim is for every district to have a nursery with 10,000 seedlings. Swamps Rwanda not only has numerous hills but also numerous swamps at the bottom of the hills. In the past many of these were not cultivated because of the expense of drainage and managing the swamp. However, given the pressure on land and more erratic climactic conditions that affect crops traditionally grown on the hillsides, developing swamps would provide new arable space, for beans, rice or cassava. Underground water also means that agricultural production is less dependent on rainfall and can survive periods of drought. After a long drought which killed livestock in Kenya, floods took what was left. This man lost most of his goats and sheep. Photo: International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies The RRCS has one such project which began several years ago – some 10 hectares of the Agatenga swamp are now successfully cultivated, providing beans, cassava and rice to nearby communities. This part of Rwanda has been hit by drought in the last few years and up to 30% of the people are foodinsecure. Developing projects such as this is part of the RRCS strategy to promote the capacity of local communities to cope. Emmanuel Munyentwari is one farmer who works there. He has his own plot of land on the hillside but there he is more dependent on rain. “Last year rain was expected in September but it came only in November,” he says, “so we couldn’t plant until November and people had little to eat – there were food shortages.” But the extra crops that he grows in the swamp project are useful. His own harvest is low and he is really not growing enough food to eat. His dream, he says, is that one day he will be able to afford school fees to send his wife back to school. “The Red Cross did a good job here,” he adds, “and I hope it can expand.” Training volunteers and mobilising the community is key to dealing with climate-change impacts. Yvonne Kabagire is a communications officer at the RRCS and is also a radio presenter with her own 15-minute programme, Rwanda Red Cross Humanitarian Action. Every week she covers subjects such as HIV/ AIDS, the environment, drought, floods and disasters, and commands an audience of no less than 70% of the entire population of Rwanda. Kabagire sees radio as an important tool in disseminating information on climate change. “People need to know about it because our country is not an island,” she explains. “They need to understand the phenomenon and how they can have a role in building coping strategies.”