* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download HUMAN EVOLUTION CART

Mitochondrial Eve wikipedia , lookup

Origin of language wikipedia , lookup

Archaic human admixture with modern humans wikipedia , lookup

Multiregional origin of modern humans wikipedia , lookup

Before the Dawn (book) wikipedia , lookup

Craniometry wikipedia , lookup

Discovery of human antiquity wikipedia , lookup

Evolutionary origin of religions wikipedia , lookup

Behavioral modernity wikipedia , lookup

Human evolutionary genetics wikipedia , lookup

Homo floresiensis wikipedia , lookup

History of anthropometry wikipedia , lookup

Recent African origin of modern humans wikipedia , lookup

Anatomically modern human wikipedia , lookup

Homo heidelbergensis wikipedia , lookup

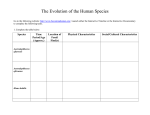

Table of Contents

Human Evolution Overview

and Specimen Descriptions

Overview

Purpose............................................................................................................................................... 2

Concepts............................................................................................................................................. 2

What distinguishes human ancestors from non-human ancestors?.................................................... 2

Locomotion and Bipedalism ........................................................................................................... 3

Advantages of Bipedalism ......................................................................................................... 3

Disadvantages of Bipedalism..................................................................................................... 4

Human Brain Evolution .................................................................................................................. 4

Hominin Species and their Ages ........................................................................................................ 5

Species similar to Homo habilis ................................................................................................... 10

Tools ................................................................................................................................................ 13

Oldowan ........................................................................................................................................ 13

Acheulean ..................................................................................................................................... 13

Mousterian .................................................................................................................................... 13

Upper Paleolithic .......................................................................................................................... 14

What Paleoanthropology and DNA Tell Us about Human Migration ............................................. 14

Multiregional Evolution ................................................................................................................ 14

The Out of Africa Theory ............................................................................................................. 14

Bibliography .................................................................................................................................... 15

Specimen Descriptions

Descriptions of Hominin Skulls in the Human Evolution Specimen Collection and in TAC ......... 16

Australopithecus afarensis ............................................................................................................ 16

Paranthropus boisei ...................................................................................................................... 17

Homo habilis ................................................................................................................................. 18

Homo erectus ................................................................................................................................ 19

Homo heidelbergensis (also archaic Homo sapiens) ................................................................... 20

Homo neanderthalensis ................................................................................................................ 21

Homo sapiens ................................................................................................................................ 22

Human Evolution

Overview

PURPOSE

This cart strives to stimulate curiosity and understanding about human origins. Docents can use

the Human Evolution Cart to demonstrate and reinforce concepts underlining human evolution and

explain evidence underlying these concepts. The cart may also be used to reinforce the Human

Evolution exhibit in Tusher African Center.

Human origin is an intensely active – and fun – area of scientific research. Scientists generate

alternative hypotheses to explain something, and enter into spirited and sometimes heated debates

to justify their own hypothesis. This is a good thing! It shows how science works. Flawed

hypotheses eventually can no longer withstand the “light of day” and lose adherents. The best

hypotheses gain adherents, and may become so widely accepted that they become scientific

theories. But even theories are constantly being tested.

CONCEPTS

The field of science that studies the human fossil record is known as paleoanthropology. It is the

intersection of paleontology (the study of ancient life forms) and anthropology (the study of

humans).

New biochemical evidence indicates that while gorillas diverged from our common ancestor

between 9 and 10 million years ago, the split between human ancestors and chimpanzee-bonobo

ancestors occurred between 5 and 7 million years ago. Even so, humans, chimps, bonobos, and

gorillas are more closely related to one another than they are to orangutans. Recent taxonomic

changes reflect this knowledge: humans and human ancestors (including extinct variants) are now

called hominins rather than hominids.

WHAT DISTINGUISHES HUMAN ANCESTORS FROM NON-HUMAN ANCESTORS?

We humans are odd creatures. Our bodies are a mosaic of features shaped by natural selection

over vast periods of time, both exquisitely capable and deeply flawed. One of these features,

bipedalism (the ability to stand and walk upright on the two posterior extremities, is a crucial

distinction between humans and non-humans. Fossil discoveries tell us that the development of

bipedalism came before dental changes, and brain enlargement came much later.

By 3 million years ago, hominins were almost as efficient at bipedal walking as modern humans.

Like people, but unlike apes, hominin pelvis bones were shortened from top to bottom and bowlshaped. This made the pelvis more stable for weight support when standing or moving bipedally.

The longer, narrower ape pelvis is adapted for quadrupedal locomotion. Early hominin leg and foot

bones were also much more similar to ours than to those of apes.

This illustration compares pelvis and foot bones:

So, by comparison to the living apes, hominins have a short, flared ilium (the upper most section

of the hip bone or pelvis).

Other features distinguishing hominins from the living apes are:

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

a foramen magnum that points down (the foramen magnum is the opening in the skull

through which the spinal cord passes)

a curved lumbar (lower) spine

lengthened lower limbs

a femur that slants inward toward the knee

a strong, robust talus (ankle bone)

a strong big toe that is in line with the other toes, making it supportive and non-opposable,

an extensible knee joint

a complex two-way arch system in the foot

Hominin teeth align in a parabolic arch, while the side teeth in apes are parallel. Hominin canines

and incisors are much smaller than ape canines and incisors. A diastema, the gap between the

canine and the incisors, is absent in most hominins but may be seen in some early

Australopithecine species.

Locomotion and Bipedalism

Although Homo sapiens is not the only existing primate to walk on two feet, it is the only one to

do so habitually and to have a striding gait while doing so.

Advantages of Bipedalism

Upright walking offers these advantages:

•

•

•

•

•

It frees the hands, enabling humans to carry and manipulate objects such as tools.

It increases the energy efficiency and endurance of humans.

It is easier to see potential predators and food sources from farther away.

It increases one’s size to better dominate over others.

The impact of the Sun’s heat is lessened.

Once a creature was standing it would enjoy all of the above advantages.

Disadvantages of Bipedalism

Bipedalism is the direct cause of the following problems:

•

•

•

•

•

major spinal and lower limb problems, frequently disabling and incapacitating. The

spine is the first organ in our body to deteriorate due to wear and tear, and 80% of

people will have back problems sometime in their life. Ninety percent of people will

have significant hip, knee, or foot problems during their lives.

vascular disorders, such as varicose veins, phlebitis, and hemorrhoids – usually

disabling, not infrequently fatal

inguinal hernias – usually disabling, occasionally fatal

high blood pressure – sometimes disabling, occasionally fatal

major obstetrical problems – sometimes fatal. The evolution of bipedalism produced a

pelvis for upright walking which resulted in an obstructive birth canal for the infant.

Human bipedalism is promoted by a wide pelvis. In mammals the pelvis is also the passage

through which newborn babies pass. The evolution of large-brained hominins made birthing

through the female pelvis more difficult. In most modern births, the baby’s head is larger than

the birth canal. If there were no flexibility on either side, the baby could not be successfully

delivered.

Three mechanisms make human birth possible in response to pelvic alterations produced by

evolution to bipedalism:

1. Pelvic ligament relaxation – allowing the pelvis to partially expand.

2. Flexibility of fetal cranial bones – allowing head shape to adjust to the birth canal.

3. The ability of the fetal head to rotate as it progresses through the birth canal

Human Brain Evolution

Compared with other primates, modern humans stand out in three main respects:

• bipedalism and strident locomotion

• modified jaws and teeth

• very large brains

The human brain is very large compared to other primates, but it is smaller than that of an elephant

or a whale, both in absolute terms and with respect to body size. Still, it is capable of intricate

mental processes that no other known brain approaches. The unique behavior of humans probably

emerged from the increase in brain size during human evolution. This increase in brain size

occurred rapidly and approximately within the last four million years.

When, how, and why was there a rapid and massive increase in brain size?

•

When? This rapid increase took place between 4 million years ago and 0.400 million years

ago.

•

How? Increased locomotion led to increased freedom of hands, increased food gathering,

and a richer diet.

• Why? A diet that increased from a low calorie, low protein, low fat diet to a high protein,

high fat diet provided the extra calories and nourishment for the high-energy requirement

of the brain.

The brain is the most energy-expensive organ of the body. It requires 20% of the body’s energy in

an adult. In early life, the requirement is even greater: the brain requires 60% of the body’s energy

in infants. Only a few animals can provide the energy to support a large brain.

The intriguing observation emerges that all three distinct features of humans as contrasted with

other primates are intimately connected:

• Locomotion is crucial to food collection.

• Teeth and jaws are crucial in food processing.

• The increased energy obtained meets the needs for the high-energy demands associated

with increased brain size and functioning.

HOMININ SPECIES AND THEIR AGES

Many hominin fossils have been uncovered already, and there will certainly be new finds. Making

sense of the new finds will require painstaking work as well as restudy of specimens already

known.

A general pattern already seems clear. There is no simple linear transition from one species to a

successor species. Instead, there is a history of numerous speciations and extinctions during which

competition among diverse hominin species may have influenced the direction of hominin

evolution.

The species here are listed roughly from oldest to most recent estimated age. This ordering does

not represent an evolutionary sequence.

Each name consists of a genus name, e.g., Australopithecus, Homo, which is always capitalized,

and a species name, e.g., africanus, erectus, which is always in lower case.

Sahelanthropus tchadensi (“Toumai”) was discovered in Chad, in the southern Sahara desert. It is

dated at between six and seven million years old. Toumai is a nearly complete cranium with a very

small brain between 320 and 380 cc, comparable in size to that of a chimpanzee.

It is not known whether S. tchadensis was bipedal because no lower limb bones have been

discovered. It has both apelike and hominin features. This species may be close to the homininchimpanzee ancestor split. However, whether it was on our side of the chimp-human split or

whether this hominin should be dated before the split cannot be determined until additional fossils

are found from the same time period.

Orrorin tugenensis refers to fossils discovered in western Kenya. They include fragmentary arm

and thigh bones, lower jaws, and teeth in deposits dated to about six million years old. The limb

bones suggest that it was about the size of a female chimpanzee. Its finders claim that Orrorin was

a human ancestor adapted to both bipedalism and tree climbing. Other scientists are skeptical of

these claims since remains are fragmentary.

However, an article by Brian G. Richmond and William L. Jungers in the March 21, 2008 issue of

Science Magazine gives evidence that Orrorin walked upright. They claim that O. tugenensis

femora more closely resemble femora attributed to Australopithecus and Paranthropus then do

those of today’s apes or species of Homo. They conclude that Orrorin did not give rise to Homo

directly. Current evidence seems to indicate that an Australopithecus-like bipedal morphology

evolved early in the hominin clade and persisted successfully for most of human evolutionary

history.

Ardipithecus ramidus was first described in 1994 from teeth and jaw fragments. Over the past 15

years, fossils representing this species have been unearthed and studied by a large international

team with diverse areas of expertise. In the October 2, 2009 issue of Science, Ardipithecus

ramidus was described in great detail. To the surprise of many researchers, the female skeleton of

Ar. ramidus (nicknamed Ardi) does not look like any of our closest living primate relatives.

Ardi is a hominin species dated at 4.4 million years ago. It lived in the Afar Rift region of

northeastern Ethiopia. Research has shown Ardipithecus ramidus was a denizen of woodland with

small patches of forest. Scientists also learned that Ardi was probably more omnivorous than

chimpanzees and was likely to feed both in trees and on the ground. She was a biped still living in

two worlds: upright on the ground but also able to move on all fours on top of branches in the

trees, with an opposable big toe to grasp limbs. The hands, arms, feet, pelvis, and legs of this

fossil collectively reveal that it supported itself on its feet and palms as it moved through the trees

but lacked any characteristics typical of the suspension, vertical climbing, or knuckle-walking of

modern gorillas and chimps. On land, it engaged in a form of bipedality more primitive than that

of Australopithecus sp. Scientists believe that Ardi consumed only small amounts of openenvironment resources, arguing against the idea that inhabiting grasslands was one of the driving

forces in upright walking.

Ardipithecus ramidus is currently represented by 110 specimens, including a partial female

skeleton rescued from erosional degradation. This female individual weighed about 50 kg and

stood about 120 cm tall. Because many other individuals have been recovered, scientists were able

to determine that there was little difference in body size between males and females.

Ardi’s brain was as small as the brains of living chimpanzees. Her lower face had a muzzle that

juts out less than a chimpanzee’s. The cranial base is short from front to back, indicating that her

head balanced atop the spine as in later upright walkers. Her face is in a more vertical position

than that of a chimpanzee. The numerous teeth recovered, along with a fairly complete skull, show

that Ar. ramidus had a small face and a reduced canine/premolar complex. Tim White of

University of California, Berkeley says in his paper that these features indicate minimal social

aggression.

Ardipithecus kadabba. Another earlier species of Ardipithecus – Ar. kadabba, found in the same

location as Ar. Ramidus – is represented by a number of fragmentary fossils dating from 5.2 to 5.8

million years old. One of these fossils is a toe bone belonging to a bipedal creature, but it is a few

hundred thousand years younger than the rest of the fossils. Therefore, its identification as Ar.

kadabba is not firm.

Australopithecus anamensis. The remains of Australopithecus anamensis consist of nine fossils

from Kanapoi in Kenya and twelve teeth found in 1988 from Allia Bay in Kenya. It lived between

4.2 and 3.9 million years ago and has a mixture of primitive features in the skull and advanced

features in the body. The teeth and jaws are very similar to those of older fossil apes. A partial tibia

is strong evidence of bipedalism, and a lower humerus is extremely humanlike.

Australopithecus afarensis. Australopithecus afarensis lived between 3.9 and 3.0 million years

ago. It is a well-known species of early human, with specimens from over 300 individuals. Many

cranial features are reminiscent of our ape ancestry, such as a forward protruding face, a “Ushaped” palate with cheek teeth parallel in rows, and a small braincase averaging only 430 cc.

Australopithecus afarensis had a low forehead, a bony ridge over the eyes, a flat nose, and no chin.

The canine teeth are much smaller than those of modern apes, but larger and more pointed than

those of humans.

Skeletal bones show many significant differences between A. afarensis and its ape predecessors.

Bipedalism is seen in their pelvis and leg bones, which more closely resemble those of modern

man. Their bones show that they were very strong. Females were substantially smaller than males,

a condition known as sexual dimorphism. Height varied between about three feet six inches and

five feet (107 cm and 152 cm). The finger and toe bones are curved and proportionally longer than

in humans, but the hands are similar to humans in most other details. Most scientists consider this

evidence that A. afarensis was still partially adapted to climbing in trees; others consider it

evolutionary baggage.

Lucy

Lucy is the most famous of the Australopithecus afarensis fossils. Using potassium-argon

dating of the volcanic layers just above and below where Lucy was found, it was determined

that Lucy was about 3.2 million years old. Her fossilized skeleton was found in 1974 at Hadar

in Ethiopia. About 40% of her skeleton was found; this is much more complete than most

finds.

Australopithecus afarensis was a long-lived species that may have given rise to the several

lineages of early hominins that appeared in both eastern and southern Africa between two and

three million years ago.

There is additional, indirect evidence that Lucy and her kind were bipedal. A set of hominin

footprints was discovered in 1978 at Laetoli. These have hominin characteristics, including an

arch in the sole of the foot, and do not have the mobile big toe characteristic of apes. The

footprints’ age was estimated at 3.7 million years ago by the potassium-argon method. This is

considerably older than Lucy’s but is consistent with early A. afarensis.

The Dikika Baby Girl

Between 2000 and 2004 a paleoanthropological team led by Dr. Zeresenay Alesmeged (now

curator at the Academy) recovered the partial skeleton of a three-year-old Australopithecus

afarensis girl in the Dikika area of Ethiopia. The fossil was named Selam. The skeleton

consists of a virtually complete skull, the entire torso, and parts of the arms and legs. Even the

kneecaps are preserved. Selam’s age was estimated to be 3.3 million years old. The skeleton

represented the earliest and most complete juvenile hominin ever found – one that lived

150,000 years before Lucy.

Features of Selam’s face identify her as A. afarensis. The apparent brain size hints that A.

afarensis may have had delayed brain growth, a trait that is more characteristic of humans than

chimps. The remains also include a hyoid bone – a bone that helps anchor the tongue and

voice box. The size and shape of this bone suggests that Selam may have had a chimpanzeelike voice box. The tibia, femur, and foot demonstrate that she walked upright, even at the age

of three. While the lower part of her body indicates bipedalism, with a very human-like heel,

her upper body and the computerized imaging of her inner ear seem to indicate that she spent at

least part of the time in trees. 1

Kenyanthropus platyops. This species, named in 2001 by Maeve Leakey, was found in Kenya. It

is about 3.5 million years old with an unusual mixture of features. The size of the skull is similar

to A. afarensis and A. africanus, and it has a large, flat face and small teeth. While some

authorities have suggested that this new form may be a better ancestor for Homo than any species

of Australopithecus, more evidence is needed to establish this as a new taxon.

Australopithecus africanus. The Transvaal region of South Africa was the home to the species

Australopithecus africanus (although remains have been found in Kenya and Ethiopia also), which

lived 3.3 to 2.5 million years ago. This species was the first of the australopithecines to be

described. Raymond Dart named the genus and species in 1925 after he discovered the famous

Taung child, a fossil found in South Africa and estimated to have lived about 2.5 million years

ago. The face, teeth, and jaws as well as an endocranial cast of the brain were found. The child

was perhaps about three years old with a brain size of around 410 cc.

Australopithecus africanus was bipedal. It is similar to A. afarensis in both body shape and size

although it is possible that A. africanus had longer arms and shorter legs. Brain size is a little

larger than A. afarensis brains (between 435 and 530cc, with an average cranial capacity of 450cc).

The back teeth were a little bigger than in A. afarensis. The teeth and jaws are much larger than

those of humans, but the teeth are far more similar to humans than apes. The shape of the jaw is

fully parabolic, like that of humans, and the canine teeth are smaller than those of A. afarensis. All

in all the teeth and face of A. africanus appear less primitive than those of A. afarensis.

For years researchers considered the evolution of early humans to pass from A. afarensis to A.

africanus to early Homo. However, some researchers now believe that facial features link A.

africanus to the “robust” early hominin species of southern Africa, Paranthropus robustus.

Finding new fossils has given the experts more information to discuss and debate, but much is still

unknown.

Australopithecus afarensis and A. africanus are known as gracile australopithecines because of

their relatively lighter build, especially in the skull and teeth. (Gracile means "slender” and in

paleoanthropology is used as an antonym to "robust.”) Despite this, they were still more robust

than modern humans.

Australopithecus garhi. A new species of hominin was recovered in the Awash region of Ethiopia

in 1996 and 1997. The species has been named Australopithecus garhi. The sediments in which

the fossils were found have been dated to roughly 2.5 million years ago. The cheek teeth of A.

1

Source: Press release by the Max Planck Society, Munich, September 20, 2006

garhi are quite a bit larger than A. afarensis. However, A. garhi lacks other characteristics of the

robust forms of hominins, leading researchers to believe A. garhi is a sister taxon to the gracile

forms.

It is currently believed that A. garhi is part of the eastern African lineage descended from A.

afarensis, with a cranial capacity of around 450 cc (slightly larger than modern chimpanzees).

Aspects of the dentition are similar to early specimens of the genus Homo. Australopithecus garhi

shows human-like ratios for femur to humerus length while retaining ape-like proportions for the

length of the forearm to upper arm. This strange admixture of traits leads some scientists to

believe that A. garhi may be very close to the origin point of our own species.

“Robust” australopithecines. Australopithecus aethiopicus, A. robustus and A. boisei are known

as robust australopithecines because their skulls are more heavily built and because they had huge,

broad cheek teeth with thick enamel. They have never been serious candidates for being direct

human ancestors. Many authorities now classify them in the genus Paranthropus.

Australopithecus aethiopicus existed between 2.6 and 2.3 million years ago. It is known from one

major specimen and a few other minor specimens. The brain size (410 cc) is very small and parts

of the skull are very primitive. Other characteristics, like the massiveness of the face, jaws, and the

largest sagittal crest in any known hominin, are reminiscent of A. boisei (the sagittal crest is a bony

ridge on top of the skull to which chewing muscles attach).

Paranthropus (Australopithecus) robustus had a body similar to that of A. africanus but a larger

and more robust skull and teeth. It lived in Southern Africa between 2 and 1.5 million years ago.

The massive face is flat or dished with no forehead and large brow ridges. It has relatively small

front teeth, but massive grinding teeth in a large lower jaw. Most specimens have sagittal crests. Its

diet would have been mostly coarse, tough food that needed a lot of chewing. The average brain

size is about 530 cc. Bones excavated with P. robustus skeletons indicate that they may have been

used as digging tools.

Paranthropus boisei (formerly Zinjanthropus boisei and then Australopithecus) lived in east

Africa between 2.1 and 1.1 million years ago. It was similar to A. robustus, but the face and cheek

teeth were even more massive. The brain size is similar to P. robustus. A few experts consider P.

boisei and P. robustus to be variants of the same species.

Homo habili ("handy man”) was so called because of evidence of tools found with its remains.

Homo habilis existed between 2.4 and 1.5 million years ago. It is very similar to australopithecines

in many ways. The face is still primitive but projects less than in A. africanus. The back teeth are

smaller but still considerably larger than in modern humans. Brain size varies between 500 and

800 cc, overlapping the australopithecines at the low end and H. erectus at the high end. The brain

shape is also more humanlike. The bulge of Broca's area, essential for speech, is visible in one

H. habilis brain cast and indicates it was possibly capable of rudimentary speech. Homo habilis is

thought to have been about five feet (127 cm) tall and about 100 lb (45 kg) in weight.

The Oldowan toolkit is associated with Homo habilis. These are simple water-smoothed rocks

roughly 3–4 inches across, modified by knocking some flakes or chips off one or two faces to

make a sharp edge. According to paleoanthropologist Richard Leakey, these simple stone tools

allowed these hominins to more quickly cut meat and bones off a carcass, making the addition of

meat to the diet, through scavenging, safer and more efficient.

Homo habilis is now fully accepted as a taxon, but the H. habilis specimens may have too wide a

range of variation for a single species. It is thought that some specimens should be placed in one or

more separate species. One such species accepted by many scientists is Homo rudolfensis.

Species similar to H. Habilis

Homo rudolfensis was discovered at Koobi Fora in Kenya. The estimated age is 1.9 million years.

This is the most complete habilis-type skull known. Its brain size is 750 cc. The braincase is

modern in many respects, much less robust than any australopithecine skull and also without the

robustness and large brow ridges typical of Homo erectus. In contrast, the face is extremely large

and robust. While an increasing number of scientists have been classifying this skull as Homo

rudolfensis, others have seen resemblances to Kenyanthropus and think it may eventually be

reassigned to the genus Kenyanthropus.

Homo georgicus includes fossils found in Dmanisi, Georgia. They seem intermediate between H.

habilis and H. erectus and are about 1.8 million years old. The brain sizes vary from 600 to 680 cc.

The height would have been about four feet eleven inches (150 cm). Depending on the reference,

these fossils are also referred to as Homo erectus and Homo ergaster. This site would seem to

indicate that hominins may have left Africa sooner and at an earlier evolutionary stage than was

previously thought. In 2003 Meave Leakey announced the discovery of a skull in Kenya, dated at

1.55 million years ago, that resembles the Dmanisi skull in size and some features. This skull was

assigned to H. erectus.

Additional Homo Species

Homo erectus/Homo ergaster. Homo erectus appears to have evolved in Africa about 1.8 million

years ago. Many early H. erectus fossils were also found in Asia (Java and Zhoukoudian, a cave

outside of Beijing, China). The face has protruding jaws with large molars, no chin, thick brow

ridges, a sloping forehead, and a long low skull. Brain size varied between 750 and 1225 cc. Early

H. erectus specimens had braincases that averaged about 900 cc, while late ones had braincases

that averaged about 1100 cc. The skeleton is more robust than those of modern humans, implying

greater strength.

Homo erectus was a wide-ranging species and has been found in Africa, Asia, and Europe.

Perhaps the most striking behavioral advance associated with Homo erectus is the purposeful use

of fire: fire used consistently in the same place over a period of time. According to the journal

Science (April 29, 2004), evidence from northern Israel shows Homo erectus using controlled fire

790,000 years ago. Another accepted date and location (though some scientists are still skeptical)

is from a cave at Zhoukoudian sometime around 500,000 years ago.

Among the oldest fossils in this group are those that some authorities place in a separate species,

Homo ergaster. The oldest, well-established find, from East Turkana in Kenya, is dated at 1.78

million years ago. In some ways this fossil is typical of H. erectus with its heavy brow ridges, a

prognathous face, a sloping forehead, and an elongated profile. In other ways, however, the

Turkana skull differs from others labeled as H. erectus. It is thinner and higher in profile and lacks

an obvious depression just behind the brow ridge; it also has smaller facial bones. These modernlooking features are what have led to its placement in the species H. ergaster.

Many researchers now separate Homo erectus into two into distinct species: Homo ergaster for

early African "Homo erectus" and Homo erectus for later populations, mainly in Asia. Since

modern humans share the same differences as H. ergaster with the Asian H. erectus, scientists

consider H. ergaster (formerly early H. erectus) as the probable ancestor of later Homo

populations. Not all researchers agree with the Homo erectus/Homo ergaster separation. Tim

White believes Homo ergaster is simply a geographical variation of Homo erectus, and Zeresenay

Alemseged also believes Homo ergaster and Homo erectus are one species.

Evidence of this comes from one of the oldest and most complete fossils in the H. erectus/ergaster

group –Turkana Boy. It is the nearly whole skeleton of an eleven or twelve year-old boy found at

West Turkana in Kenya and is dated at 1.6 million years ago. (This specimen is referred to as

Homo ergaster in most references.) The brain size was 880 cc and would have been 910 cc at

adulthood. The boy was five feet three inches (160 cm) tall, and he might have been about six feet

one inch (185 cm) as an adult. Except for the skull and despite several small differences, the

skeleton is very similar to that of modern boys.

By 1.6 million years ago, an advance in stone tool technology is identified with H.

ergaster/erectus. Known as the Achulean stone tool industry, it consisted of large cutting tools,

primarily hand axes and cleavers.

Homo antecessor. Homo antecessor was named for fossils found at the Spanish cave site of

Atapuerca. They date to at least 780,000 years ago. This makes them the oldest confirmed

European hominins. The mid-facial area of antecessor seems very modern, but other parts of the

skull such as the teeth, forehead and brow ridges are much more primitive. Many scientists are

doubtful about the validity of antecessor, partly because its definition is based on a juvenile

specimen.

Homo sapiens (archaic) (also Homo heidelbergensis). Archaic forms of Homo sapiens first appear

about 500,000 years ago. The term covers a diverse group of skulls which have features of both

Homo erectus and modern humans. The brain size is larger than H. erectus and smaller than most

modern humans, averaging about 1200–1300 cc. The skull is more rounded than in H. erectus. The

skeleton and teeth are usually less robust than H. erectus but more robust than modern humans.

Many still have large brow ridges and receding foreheads and chins.

There is no clear dividing line between late H. erectus and archaic H. sapiens, and fossils between

500,000 and 200,000 years ago are difficult to classify as one or the other. They are geographically

widespread and cover about 275,000 years. The Levallois toolkit is associated with these people

and began to appear about 200,000 years ago.

Homo neanderthalensis. Neanderthals (pronounced neandertal) inhabited Europe and western

Asia during the latter part of the Pleistocene, between 230,000 and 30,000 years ago. The climate

was much colder than it is today, and several glaciations (Ice Ages) occurred during this time.

Neanderthals mostly lived in cold climates, and their body proportions are similar to those of

modern cold-adapted peoples: short and solid with short limbs. Men averaged about five feet six

inches (168 cm) tall. Their bones are thick and heavy and show signs of powerful muscle

attachments. Neanderthals would have been extraordinarily strong by modern standards. Their

skeletons show that they endured brutally hard lives.

The average brain size is about 1450 cc, slightly larger than that of modern humans. The braincase

is longer and lower than that of modern humans with a marked bulge at the back of the skull. Like

H. erectus, they had a protruding jaw and receding forehead. The chin was usually weak. The mid-

facial area also protrudes, a feature that is not found in H. erectus or H. sapiens and may be an

adaptation to cold.

A large number of tools and weapons, more advanced than those of H. erectus, have been found.

Neanderthals were formidable hunters and are the first people known to have buried their dead.

Some burials show evidence that these graves were adorned with offerings such as flowers. This

cultural advance, which represents an awareness and recognition of life and death, may have first

been practiced by the Neanderthals.

Neanderthal localities are known today from Spain to Uzbekistan. Several sites near Qafzeh Cave,

Israel, suggest that Neanderthals arrived in the region after modern H. sapiens. This indicates that

the population of modern humans in this area was not descended from Neanderthals, and that there

was some period of coexistence or an alternating series of migrations into this region. Neanderthals

disappeared from the fossil record about 30,000 years ago and were replaced in Europe by

anatomically modern forms.

Neanderthals and modern humans are very similar anatomically, so similar in fact, that some

scientists proposed that Neanderthals and modern humans represent two subspecies: Homo sapiens

neanderthalensis and Homo sapiens sapiens. Neanderthal DNA, however, is quite distinct from

that of modern humans. This suggests that H. sapiens and H. neanderthalensis were separate

species rather than subspecies. Either way, Neanderthals represent a very close evolutionary

relative of modern humans.

Homo floresiensis was discovered on the Indonesian island of Flores. Fossils have been

discovered from a number of individuals (about fourteen). The most complete fossil is of an adult

female about three feet four inches (one meter) tall with a brain size of 417 cc. Other fossils that

were found indicate that this was a normal size for H. floresiensis.

Homo floresiensis is still somewhat of an enigma, as some of the features in her trunk and limbs

are quite primitive (extremely long feet, no arch, short shin and thigh bones, an ape-like wrist

bone, etc.). The brain is quite small but has a number of modern characteristics. Based on recent

studies, it now seems that from the neck down, H. floresiensis looks more like Lucy and the other

australopithecines. From the neck up, however, her 417 cc brain has cranial features that mark her

as a member of Homo. The latest studies of H. floresiensis seem to indicate that this species is a

very primitive hominin; artifacts found with these fossils seem to bear this out.

Researchers originally believed H. floresiensis was a descendant of H. erectus that became

dwarfed due to the limited resources on the island of Flores. The latest research suggests,

however, that H. floresiensis is significantly more primitive than H. erectus and might have

evolved either right before or right after H. habilis. The study implies that H. floresiensis evolved

in Africa along with other early Homo species, was fairly small when the species reached Flores,

and could have undergone some additional dwarfing while on the island.

There are still some scientists who doubt that H. floresiensis represents a new species but is a

modern human with a disease that results in a small body and brain. However, scientists who

believe H. floresiensis is a new species have presented anatomical evidence against each of the

proposed diagnoses. One noted scientist summed it up neatly when he stated that we need more

discoveries from Flores, the neighboring islands, and other Asian locations. 2

Homo sapiens. Modern Homo sapiens first appear about 195,000 years ago. They have an

average brain size of about 1350 cc. The forehead rises sharply, eyebrow ridges are very small or

absent, the chin is prominent, and the skeleton is very gracile. About 40,000 years ago, with the

appearance of the Cro-Magnon culture, toolkits started becoming markedly more sophisticated.

Fine artwork, in the form of decorated tools, beads, ivory carvings of humans and animals, clay

figurines, musical instruments, and spectacular cave paintings, appeared over the next 20,000

years.

Even within the last 100,000 years, long-term trends towards smaller molars and decreased

robustness are seen. The face, jaw and teeth of Mesolithic humans (about 10,000 years ago) are

about 10% more robust than ours. Upper Paleolithic humans (about 30,000 years ago) are about

20–30% more robust than the modern condition in Europe and Asia. Interestingly, some modern

humans (aboriginal Australians) have tooth sizes more typical of archaic H. sapiens. The smallest

tooth sizes are found in those areas where food-processing techniques have been used for the

longest time. This is a probable example of natural selection that has occurred within the last

10,000 years.

TOOLS

Oldowan

Oldowan tools are the oldest known tools. They appeared first in Ethiopia about 2.4 million years

ago and are associated primarily with Homo habilis.

Many Oldowan tools were made by a single blow of one rock against another to create a sharpedged flake. Flakes were used primarily as cutters to dismember game carcasses and to strip tough

plants. Large shaped stones were used as choppers, scrapers, and pounders.

Acheulean

The Acheulean tool industry first appeared around 1.5 million years ago in East Central Africa.

These tools are associated with Homo ergaster and western Homo erectus. The key innovations

were (1) chipping the stone from both sides to produce a symmetrical or bifacial cutting edge, (2)

the shaping of an entire stone into a recognizable and repeated tool form – oval, pear shaped hand

axes, and (3) variations in tool forms for different tool use.

Mousterian

The Mousterian industry is associated with the Neanderthals. These forms displayed a wide range

of specialized shapes: cutting tools that included notched flakes, serrated flakes, and flake blades

designed to be spear points or lances, as well as scrapers.

2

From Nov. 2009 Scientific American, Oct. 17, 2009 Science Now (AAAS), and N.Y. Times Science Oct. 18, 2009.

Upper Paleolithic

The Upper Paleolithic industry, dominant from about 50,000 to 12,000 years ago, appears to have

originated independently in both Asia and in Africa. This tool making culture shows a remarkable

proliferation of tool forms, tool materials, and much greater complexity of tool making techniques,

all occurring before the advent of agriculture. Classic examples included advanced scrapers for

processing hides and for the making of darts, harpoons, fish hooks, oil lamps, rope, eyed needles,

carved figurines, and tools and pigments for paintings.

WHAT PALEOANTHROPOLOGY AND DNA TELL US ABOUT HUMAN MIGRATION

A major debate in bioanthropology has concerned the origins of modern Homo sapiens. Two

major models have been developed: (1) the Multiregional Evolution Theory or (2) the Out of

Africa Theory. The Out of Africa Theory has the most adherents.

Multiregional Evolution

The Multiregional Evolution proponents believe that there is no single home for modern humanity.

Beginning with Homo erectus, hominins migrated from Africa to every part of the Old World.

Over time they evolved modern forms locally, with some regional differences. Interbreeding with

one another as well as with other migrating populations of Homo maintained a gene flow and kept

all humankind one species.

The Out of Africa Theory

Proponents of this theory propose that modern humans evolved as a separate species 200,000–

150,000 years ago in Africa. They then spread throughout the Old World, replacing populations of

archaic humans. This conclusion is based on fossil, cultural and DNA evidence.

Recent analyses show that the modern worldwide pattern of skull shapes closely matches the

genetic data. The diversity of cranial shape within a population falls off the farther it is from

Africa, implying that Homo sapiens first arose in Africa. Contemporary DNA data also reveal that

human beings are remarkably homogeneous, with relatively little genetic variation. The low

amount of genetic variation in modern human populations suggests that our origins may reflect a

relatively small founding population for Homo sapiens.

There is no doubt that Africa is the birthplace of humanity, and the above-mentioned factors are

more consistent with the Out of Africa hypothesis than with the Multiregional hypothesis.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Begun, David R. Apes. Scientific American: Vol. xx, 75-83.

DeSalle, Rob and Tattersall, Ian. Human Origins: What Bones and Genomes Tell Us About

Ourselves. Texas A & M University Press, 2008.

Gibbons, Ann. 2007. Fossil Teeth from Ethiopia Support Early, African Origin for Apes. Science

317: 1016-1017.

Park, Michael Alan. 2008. Biological Anthropology. McGraw-Hill: New York.

Richmond, Brian G. and Jungers, William L. 2008. Orrorin tugenensis femoral morphology and

the evolution of hominin bipedalism. Science 319: 1662-1665.

Tattersall, Ian Tattersall. 1998. Becoming Human. Harcourt Brace & Company: New York.

Tattersall, Ian. 2000. Once We Were Not Alone. Scientific American 282 (1): 56-62.

Tattersall, Ian and Schwartz. 2001. Extinct Humans. Westview Press: Boulder, CO.

Wells, Spencer. 2002. The Journey of Man. Random House: New York.

Zihlman, Adrienne L. 2000. The Human Evolution Coloring Book 2nd edition. HarperResource:

New York.

Zimmer, Carl. 2005. Smithsonian Intimate Guide to Human Origins. HarperCollins Publishers

Inc: New York.

Science Magazine, Volume 326, October 2, 2009.

Scientific American Magazine, November 2009.

http://www.handprint.com/LS/ANC/stones.html

http://www.primates.com/homo/outofafrica.html Source: Max Planck Society

http://www.actionbioscience.org/evolution/johanson.html

SPECIMEN DESCRIPTIONS

HOMININ SKULLS IN HUMAN EVOLUTION SPECIMEN COLLECTION

AND IN TAC

Australopithecus afarensis

Fossil Record: 3.9–3.0 million years ago; the most widely-known Australopithecine fossil, Lucy,

is estimated to be around 3.2 million years old.

Brain size: Australopithecine brains fall somewhere between the 375 cc and 550 cc range. Some

paleontologists put the size of Lucy’s brain at around 380 cc. Her skull was incomplete.

Diet: Mostly mixed vegetables, fruit, and leaves; no direct evidence of meat eating. However,

there is some evidence, based on microscopic examination of tooth wear and carbon residue, that

A. afarensis may have eaten plant-eating insects or scavenged other plant-eating animals.

Habitat and Distribution: Eastern Africa

Behavior, Adaptations, and Things To Notice:

• Bipedalism in the pelvis and leg bones of this species.

• Cranial features reminiscent of our ape ancestry, such as a forward protruding face.

• U-shaped palate with cheek teeth parallel in rows, similar to an ape, rather than the

parabolic shape of a modern human.

• Small braincase, low forehead, bony ridge over the eyes, a flat nose, and no chin.

• Much smaller canine teeth than those of modern apes, but larger and more pointed than

those of humans.

• Even though the fossil Lucy was an adult, she was very small. She was only 3-1/2 feet tall

and weighed somewhere between 57–64 lbs (26 kg to 29 kg).

• Lucy’s third molars had erupted so this was her adult weight. This indicates that she was

female because the remains of A. afarensis show clear evidence of sexual dimorphism and

her weight is on the low end for an A. afarensis adult.

• “Lucy is as important today as she was 30-plus years ago,” says Nina Jablonski, Penn State

anthropologist. “Before Lucy, we really had no idea that ‘early’ hominids were small and

very apelike in most attributes. Paleoanthropology has never been the same.”

Paranthropus boisei

(Australopithecus boisei, Zinjanthropus boisei)

Fossil Record: The specimen that defined the species is the famous Zinjanthropus found by Mary

and Louis Leakey at Olduvai Gorge in 1959. This hominin lived between 2.1 and 1.1 million

years ago and had an average brain size of about 530 cc.

Diet: Mixed, tough, vegetable diet that required lots of chewing.

Habitat and Distribution: Specimens attributed to P. boisei have been found mostly in Ethiopia,

Tanzania, and Kenya in East Africa. The Olduvai Basin was occupied by a lake, fed by streams

from the nearby highlands. Lake reed beds flourished, yielding to trees and finally to an arid

grassland, as one became more removed from the lake. In the Omo basin of Ethiopia,

Paranthropus-yielding deposits span a period in which the climate dried considerably. On the open

plains, vegetation became sparser with time, though forests may have remained available along

watercourses. Paranthropus living in the vicinity of Lake Turkana also had to deal with a

fluctuating environment. Basically they lived in a dry, grassland environment.

Behavior, Adaptations, and Things to Notice:

• Although, most robust forms were similar in body and brain size to A. africanus, the

members of the genus Paranthropus were considerably more robust in all features

involving chewing.

• The most striking feature of P. boisei is its huge teeth; it has the largest teeth found in any

hominin group so far. These huge premolars and molars provide an enormous flat grinding

surface. (Its front teeth are relatively small.)

• The jaws are large and heavy, and there is a large sagittal crest (all indications of a tough,

fibrous, vegetable diet).

• This hominin has a very long, flat face with no forehead and large brow ridges. It also has

an elongated braincase. This species has been described as hyper-robust.

Homo habilis

Fossil Record: Homo habilis existed between 2.4 and 1.5 million years ago. The brain size

varied between 500 and 800 cc, overlapping the australopithecines at the low end and H. erectus at

the high end. While Homo habilis is now fully accepted as a taxon, some H. habilis specimens

may have too wide a range of variation to be considered one species. Some specimens have been

placed in the species known as Homo rudolfensis. (See Overview for more information).

Habitat and Distribution: Tanzania, Kenya, Ethiopia, and perhaps southern Africa.

Diet: Evidence found with early tools, known as the Oldowan toolkit, included both meat and

plant food. Most of the animal bones found at these early Homo sites consisted of lower leg bones

and skulls of antelopes, about the only part of an animal left after a large carnivore has finished

eating. However, since such bones are rich in marrow, it is hypothesized that these early hominins

probably cut off what little meat remained on these bones and then broke them apart for the

marrow inside.

According to paleoanthropologist, Richard Leakey, these simple stone tools allowed these

hominins to more quickly cut meat and bones off a carcass, making the addition of meat to the

diet, through scavenging, safer and more efficient.

Behavior, Adaptations, and Things to Notice:

• Notice that Homo habilis is similar to the australopithecines in many ways. The face is still

primitive but projects less than in A. africanus. The back teeth are smaller, but still

considerably larger than in modern humans.

• The brain shape is more humanlike. The bulge of Broca’s area, essential for speech, is

visible in one H. habilis brain cast, and indicates it was possibly capable of rudimentary

speech.

• H. habilis is thought to have been about five feet (127 cm) tall and weighed about 100 lbs.

(45 kg). Some specimens of H. habilis seem to show evidence of continued arboreal

ability.

Homo erectus

Fossil Record: Homo erectus lived between 1.8 million and 300,000 years ago.

Brain size: Varies between 750 and 1225cc; early H. erectus specimens had brain sizes averaging

around 900 cc, while later ones average about 1100 cc.

Habitat and Distribution: While Homo habilis and all the australopithecines are found only in

Africa, H. erectus was wide-ranging, found in Africa, Asia, and Europe. Redating some Asian

fossils, scientists have found that H. erectus may have been in Indonesia as early as 1.8 million

years ago.

Diet: Meat as well as plant foods. There is no compelling evidence for cooperative big game

hunting. Bones found at sites where meat was eaten suggest scavenging rather than large hunts.

H. erectus was probably able to kill and eat smaller animals when the opportunity presented itself.

Behavior, Adaptations, and Things to Notice:

• From the neck up, Homo ergaster/erectus is quite distinct from the earlier forms of Homo

in brain size. However, the skull still retains some primitive features that distinguish it

from modern Homo sapiens. Homo erectus had a protruding jaw, receding forehead, a

heavy brow ridge, and a flat, thick skull cap. From the neck down, however, H.

erectus/ergaster is essentially modern.

• Homo erectus made stone tools by taking flakes off a core stone, controlling the shape of

the whole core tool. This tool-making tradition is called the Acheulian technique and is

represented by the hand axe, the all-purpose tool of its time. They also made tools with

sharp, straight edges, called cleavers. (See “Tools” in the Overview.)

• There is also evidence of shelter-making with this species. Japanese archaeologists have

discovered the remains of what is believed to be the world's oldest artificial structure on a

hillside at Chichibu, north of Tokyo. The site has been dated to half a million years ago, a

time when Homo erectus lived in the region.

• Before the discovery, the oldest remains of a structure were those at Terra Amata in France,

from around 200,000 to 400,000 years ago.

• H. erectus used fire between 790,000 and 500,000 years ago. Flint implements and hearths

were found at a site in northern Israel, dated at 790,000 years. Fire provides warmth,

protection from wild animals, a way to cook meat, making it more digestible and easier to

chew, and it extends daylight, allowing more group interaction.

• This species had vocal tracts more like modern humans, positioned lower in the throat, and

allowing for a greater range and speed of sound production. Therefore, they could have

produced many sounds with precise differences. Whether they did or not is unknown.

Homo heidelbergensis (also archaic Homo sapiens)

Fossil Record: Homo heidelbergensis first appeared about 500,000 years ago. The species name

H. heidelbergensis covers a group of skulls that have features of both H. erectus and modern

humans.

Brain size: Larger than H. erectus, smaller than modern humans (avg. 1200–1300 cc).

Habitat and Distribution: Africa (East and South), Europe (several sites), but few in Asia.

Diet: Omnivorous

Behavior, Adaptations, and Things to Notice:

• Skull is more rounded than in H. erectus: its face is large, and its nose is broad; skeleton

and teeth are usually less robust than H. erectus, but more robust than modern humans.

Many still have brow ridges, receding foreheads, and chins.

• Shelters of these people were found at site of Terra Amata, overlooking Bay of Nice in

France (dated 400,000 years ago). The hearth, on which fire had been maintained, was

preserved; broken animal bones, charcoal, and worked stones were found in shelters.

• About 200,000 years ago, a new stone-working technology appeared that was associated

with H. heidelbergensis, the Levallois technique. (For more information on this toolkit, see

“Tools” in the Overview.)

• This new method provided long cutting edges along sides of flake and greater control over

shape of tool.

• This technology laid the groundwork for later technological advances in tool-making.

Direct evidence of wooden implements also comes from the time of H. heidelbergensis: in

England at the site of Clacton, a preserved 300,000 year old wooden spear point made from

yew; and spears, dated at 400,000 years, at a site in Germany.

Homo neanderthalensis

Fossil Record: 230,000 to 30,000 years ago.

Brain Size: 1450 cc (average), slightly larger than modern human brain.

Habitat and Distribution: Neanderthals inhabited Europe and western Asia during the latter part

of the Pleistocene (230,000 to 30,000 years ago), adapting to extremely cold climatic conditions.

Diet: They were dependent on large game animals that abounded during this time. Animals found

associated with Neanderthal remains include reindeer, deer, ibex (wild goat), aurochs (wild ox),

horse, woolly rhinoceros, bison, bear, and elk.

Behavior, Adaptations, and Things to Notice:

• Their toolkit is more advanced than that of H. erectus or H. heidelbergensis, and is known

as Mousterian technology. This technology represented a refinement of the basic prepared

core technique. A large number of tools and weapons have been found, indicating the

Neanderthal were formidable hunters. (See “Tools” in the Overview for more

information.)

• At least thirty-six Neanderthal sites show evidence of intentional internment of the dead,

and in some graves there were remains of offerings: stone tools, animal bones, and possibly

flowers.

• It has also been suggested that Neanderthals were among the first to care for their elderly,

ill and injured. Recent reexamination of this idea indicates that the vast majority of

Neanderthals died before the age of 40.

• On the other hand, there is a skeleton of a man from Shanidar in Iraq that shows signs of

injuries, which may have resulted in blindness and the loss of one arm. Upon examination,

it seems he lived with this condition for sometime; this has led researchers to conclude that

he was cared for by his comrades.

• A hyoid bone found at the Kebara site in Israel appears fully modern. This indicates that

the vocal tract of the Neanderthals was like ours, and that they were capable of making the

sounds we make.

Homo sapiens

Fossil Record: Modern Homo sapiens first appear about 195,000 years ago.

Brain size: Averages about 1350 cc.

Habitat and Distribution: Transitional forms (fossils exhibiting both archaic and modern traits)

have been found in Kenya, South Africa, Ethiopia, Tanzania, and Morocco and range in age from

100,000 to 300,000 years old. Modern humans also appeared the earliest in Africa and later

migrated into Southwest Asia, Europe and East Asia. Later still, modern humans migrated to

Australia, the islands of the Pacific, and North and South America.

Diet: Homo sapiens utilized the animal and/or plant resources found in their varied environments.

Behavior, Adaptations, and Things to Notice:

• These people are anatomically modern. Modern humans do not exhibit a prognathous

profile: the face is flat, there are no heavy brow ridges, the skull is globular rather than

elongated, and the forehead is high and nearly vertical.

• The face is smaller and narrower than earlier species, and there is a protruding chin.

• Modern humans are less robustly built than either H. erectus or H. neanderthalensis. Even

so, humans that lived 30,000 years ago were somewhat more muscular and robust than

humans living today. Because these early Homo sapiens were anatomically the same as we

are, they were fully capable of making all the sounds necessary for speech.

• Beginning around 40,000 years ago, with the appearance of the Cro-Magnon culture in

France, toolkits started to become markedly more sophisticated. Tools during this time

were made from stone, bone, antler, wood, and ivory. Most were practical, such as

harpoons, spear points, and shaft straighteners, but even these practical items were often

beautifully decorated.

• Cro-Magnon man hafted stone flakes, and by at least 26,000 years ago, the invention of

eyed bone needles shows that clothing was being carefully made.

• Art is seen during the Upper Paleolithic in some of its most striking and beautiful forms.

Cave sites in France and Spain have yielded beautiful paintings. There are also carvings of

humans and animals in stone, bone, antler, and ivory, as well as clay figurines and musical

instruments. There is also evidence of long distance trading for materials of decorative or

utilitarian value; for example, amber from the Baltic has been found in Upper Paleolithic

sites in southern Europe, and Mediterranean seashells have turned up at sites in the

Ukraine.

• As the Upper Paleolithic continued, big-game hunting became a way of life, especially for

people living in glacial conditions with limited plant resources.

• Also, during this time period, people began relying less and less on caves and rock shelters

in which to live and more and more on shelters they built themselves.