* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download as a PDF

Chinese grammar wikipedia , lookup

Kannada grammar wikipedia , lookup

Ojibwe grammar wikipedia , lookup

Construction grammar wikipedia , lookup

Udmurt grammar wikipedia , lookup

Sanskrit grammar wikipedia , lookup

English clause syntax wikipedia , lookup

French grammar wikipedia , lookup

Modern Greek grammar wikipedia , lookup

Navajo grammar wikipedia , lookup

Old Norse morphology wikipedia , lookup

Portuguese grammar wikipedia , lookup

Macedonian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Proto-Indo-European verbs wikipedia , lookup

Polish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Latin syntax wikipedia , lookup

Japanese grammar wikipedia , lookup

Modern Hebrew grammar wikipedia , lookup

Scottish Gaelic grammar wikipedia , lookup

Ukrainian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Ancient Greek grammar wikipedia , lookup

Germanic strong verb wikipedia , lookup

Old Irish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Swedish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Spanish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Georgian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Germanic weak verb wikipedia , lookup

Latin conjugation wikipedia , lookup

Icelandic grammar wikipedia , lookup

Sotho verbs wikipedia , lookup

Lexical semantics wikipedia , lookup

Yiddish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Hungarian verbs wikipedia , lookup

English verbs wikipedia , lookup

Old English grammar wikipedia , lookup

Pipil grammar wikipedia , lookup

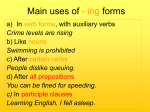

point and counterpoint The sequencing of verbal-complement structures Walter Petrovitz In this section we present contrasting views on a topic of current interest. The first article is one that has been reviewed by the editorial panel and acccepted for publication; the second is a commissioned response, to which the author of the original article is invited to make a brief reply. Reactions from readers are particularly sought, either in the form of a letter to the Editor, or as a brief article (no more than 1,250 words), which will be considered for publication in the normal way. Gerunds and infinitives are among the most diªcult topics to teach, and a continuing source of errors even among advanced learners. Treated as merely structural variants, these forms are usually grouped into a single grammar unit filled with di¤ering syntactic specifications and long lists of verbs grouped according to their complement type. Significant grammatical distinctions between gerunds and infinitives, as well as pedagogical considerations, suggest that they should be separated and taught at di¤erent points in a grammar syllabus. This article presents a concise review of the linguistic evidence concerning important di¤erences between gerunds and infinitives, and makes recommendations on the sequencing of these topics within a course of instruction. Introduction There are a number of reasons for the diªculties students encounter with regard to gerunds and infinitives. First, these forms seem to contradict what they have learnt about English verb morphology. The formal presentation of gerunds and infinitives is normally begun once students have some degree of familiarity with the comparatively more principled system of finite verbs. Suddenly their attention is drawn to participles without auxiliaries, and to verb forms inflected neither for the person and number of their subjects nor consistently for the temporal context. Second, infinitive and gerund constructions possess, to varying degrees, some of the characteristics of clauses, making their relationship to the larger sentence sometimes diªcult to comprehend. Third, the choice of either gerund or infinitive is presented as a largely arbitrary matter. 172 ELT Journal Volume 55/2 April 2001 © Oxford University Press articles welcome The common practice in ELT is to introduce infinitives and gerunds at the same time in a single unit of instruction, as reflected in most grammar texts (see, for example, Azar 1989, Eastwood 1994, Murphy 1994). Although certain general properties of these forms will be discussed, the present study will focus on the heart of the diªculty with this topic, and the most frequent source of student error: the use of the simple gerund (i.e. lacking an expressed independent subject) and infinitive complements of verbs. The claim will be made here that gerunds and infinitives di¤er significantly enough to deserve distinct pedagogical treatment. Certain similarities between modals and infinitive-complement verbs will be considered, and an alternative sequence of presentation suggested. ‘I’ve got a little list!’ In more ways than one, an instructor teaching gerunds and infinitives may feel like Gilbert and Sullivan’s Lord High Executioner, and students justifiably yearn to be set ‘from scholastic trammels free’ upon seeing in their grammar texts the disheartening pages of verbs, all organized on the basis of whether they are followed by a gerund or an infinitive. Memorization, even if possible, would be of little value for spontaneous language use, and these enumerations are not entirely satisfactory even as reference material, since, despite its length, the list of gerundcomplement verbs is never really complete. It is doubtful, for example, that any summary of such verbs has ever contained any of the main verbs found in 1: 1 a The coach criticized drinking beer before the game. b The law encourages conserving natural resources. c We can’t defend building such a monstrosity. The demands made by such a large amount of material would be bad enough, but defensible if the forms in question represented a uniform grammatical phenomenon. There is ample reason to believe, however, that this is not the case. Di¤erences between gerunds and infinitives Although they are usually grouped together in textbooks because of the grammatical functions they purportedly share, infinitives and gerunds di¤er considerably even here. For example, infinitives are relatively rare in subject position and cannot serve as the objects of prepositions, while gerunds are commonly found in these syntactic environments. (For a detailed discussion of these and other distinctions, see Emonds 1972, Quirk et al. 1972, and Horn 1975.) More important, however, than the syntactic di¤erences, at least with regard to the sequencing of these structures within the syllabus, are the lexical and semantic distinctions, which will be discussed in the following sections. Productivity As illustrated in 1, gerund complements can easily be found with verbs that are not on any of the standard lists, which are deceiving in the way they are presented. While it would appear from grammar texts that verbs taking gerund complements are approximately equal in number to those taking infinitive complements, the former are far more numerous, and have never been exhaustively tallied. Even the lengthy, and supposedly comprehensive, gerund-complement verb list in Householder (1964) is The sequencing of verbal-complement structures articles 173 welcome incomplete. The reason for this is that gerunds possess the distributional properties of noun phrases, and may therefore be used with any semantically compatible transitive verbs, except those which are reserved exclusively for the infinitive. In contrast, the infinitive-complement structure is no longer productive in English because it is associated with a fixed set of verbs to which none may be added. Thus, aside from being a dull and time-consuming task, marching students through various lists of verbs may cause them to form incorrect hypotheses about the grammar of English: either that once the lists are mastered, every occurrence of infinitive and gerund complements will be accounted for, or that for every verb they encounter they will have to learn the complement type. Clearly, a more reasonable approach would be to adopt the same strategy followed with other non-productive forms, such as irregular verbs, namely to focus attention on them, and simply indicate that the productive forms are to be used elsewhere. Aspect The analysis presented in Bolinger (1968) broadly associates gerunds and infinitives with a perfect, and a hypothetical or future aspect respectively (Bolinger uses the terms reification vs. hypothesis or potentiality). This di¤erence is most tangible with those verbs that may take either complement: 2 a Bill should remember closing the window. b Bill should remember to close the window. Of course, the aspect is relative to the tense of the main verb: whenever the remembering occurs, the closing is anterior in the case of the gerund, and posterior in the case of the infinitive. While not every verb taking either complement evidences such a clear-cut distinction (e.g. start and try), it is never the case that the anterior meaning is associated with the simple infinitive. See Bolinger for a more complete discussion. Although gerunds and infinitives both have perfective forms, CelceMurcia and Larsen-Freeman (1983) note that these forms are not semantically equivalent. The perfective forms of infinitives are consistently distinct in aspect from their non-perfective counterparts, as illustrated in 3: 3 a *He claims to work for a bank before taking his present job. b He claims to have worked for a bank before taking his present job. There is, however, no consistent corresponding di¤erence between simple and perfective forms of gerunds, as shown by the synonymy of 4a and 4b: 4 a He doesn’t remember working for a bank before taking his present job. b He doesn’t remember having worked for a bank before taking his present job. Here again, presenting the perfective forms of gerunds and infinitives together gives the impression that these forms are equivalent. Placing infinitives earlier in the syllabus, on the other hand, and more closely following the presentation of perfective finite verbs, would gain from the advantage of having the basic concepts fresh in the students’ minds. 174 Walter Petrovitz articles welcome Postponing gerunds to a place in the syllabus closer to dependent finite clauses would also make greater sense, since here as well, aspectual distinctions are sometimes erased, as shown in the synonymy of 5a and 5b: 5 a We should wait until the police arrive. b We should wait until the police have arrived. Understood subjects Another area in which infinitives di¤er from gerunds involves the understood subjects of these verbs. Horn (1975) noted that the unexpressed subjects of gerund complements need not be same as the subject of the sentence. Thus, in 6a, the subject of the gerund is interpreted to be the same as the subject of the main verb, but in 6b there is no such identity of reference: 6 a Robin tried soliciting money from the students. b Robin denounced soliciting money from the students. In contrast, the understood subject of a bare infinitive complement must be the same as that of the main verb: 7 Robin tried/decided/threatened to solicit money from the students. Once again, placing gerunds and infinitives within the same unit implies a semantic parallelism that is simply not there. The comparison with We see, then, that there are essential di¤erences between gerunds and modal auxiliaries infinitives in terms both of their syntactic distribution and their semantic interpretation. This should be suªcient for them to be treated as independent topics in the grammar syllabus. In addition, despite obvious grammatical di¤erences (involving inflection, question formation, and negation), infinitive-complement verbs are much more similar to modal auxiliaries with regard to the distinctions discussed above than they are to gerund-complement verbs. These similarities have implications both for the sequencing of gerunds and infinitives within the grammar syllabus, and the methods used to teach these structures. Productivity Like modals, infinitive-complement verbs belong to a closed, although admittedly larger, lexical class. Since they comprise a fixed set, they could be grouped semantically, much the way modals are often presented. Verbs with similar meanings, such as attempt, endeavour, try, and undertake, would thus be practiced together, rather than merely appearing scattered throughout a list. Low-frequency verbs which would be unfamiliar to most students could be introduced with other semantically similar verbs, as an aid to remembering both their meaning and their structural properties. Thus, verbs such as long and yearn could be presented together with want and desire. Modals are similar to some other non-productive lexical classes (such as irregular verbs) in that they are very high-frequency, and thus usually introduced early, while infinitives and gerunds are placed in a later part of the syllabus. However, research on the frequency of these structures reported in Celce-Murcia and Larsen-Freeman (1983), shows a much higher occurrence of infinitive complements than of gerund complements. This would also suggest that the teaching of infinitive The sequencing of verbal-complement structures articles 175 welcome complements should be placed at a much earlier position in the grammar syllabus, closely following the presentation of modals (an approach taken in Thomson and Martinet 1986). Aspect Hofmann (1966) noted that as with infinitive complements, the perfective forms of the verbs which may follow certain modals mark true aspectual distinctions, as shown in 8: 8 a *She must leave before we got there. b She must have left before we got there. Since the perfective forms in both constructions are similar in both form and meaning, the introduction of infinitive complements closely following modals would benefit from the students’ familiarity with these forms. Contextualized exercises using stories or pictures can be used to practise the two structures and review the forms involved, as illustrated in 9: 9 a Could John have visited his sister? b No. He claims … (to have been sick/working/delayed) Understood subjects The referential properties of the understood subjects are also the same for both modals and verbs that take the bare infinitive: the subject of the modal must be the same as that of the following verb. This allows the progression from constructions with modals to those with infinitivecomplement verbs (perhaps through the intermediate step of periphrastic modals) to proceed under a single conceptual framework regarding the agency of the complement verb. Again, contextualized activities can be used to practice both structures. These can include pronoun-reference exercises (an often neglected topic in grammar texts, although interestingly a more prominent feature of the new computerized TOEFL ), which would be especially useful when passive complements are being practiced. This leaves the question of overt subjects of infinitive complements. Up to this point, we have been considering only subjectless forms, but there are, of course, infinitives with independent subjects, such as those in 10: 10 a We urged her to take the job. b I warned you not to go. Although this may seem to be in contradiction to the claims made concerning the examples in 7, there are good reasons to regard the structures in 10 as suªciently di¤erent in nature to relegate them to a separate portion of the syllabus. First, there is only a small overlap between verbs taking simple infinite complements, and those taking infinitive complements with independent subjects. Presenting them together simply invites confusion. Second, in the latter category the full range of thematic roles are realized within the constituent. They are thus much more like noun clauses, and could be introduced at a point in the syllabus closer to this topic. Substitution exercises, as shown in 11, can be used to give students a better feel for the full range of clausal complements. 176 Walter Petrovitz articles welcome 11 a We told her to take the job. b We said that … (she should take the job) Conclusion The presentation of grammar in ELT can be greatly enriched by the findings of syntactic research. Such evidence should especially be taken into account with regard to areas which have traditionally been problematic. While certain grammatical topics present inherent and unavoidable diªculties, problems may also be caused by a misapprehension of the nature of the structures involved. This has been the case with the teaching of gerunds and infinitives, with a large amount of disparate material forced into a single teaching unit. A principled redistribution would allow for a more natural and comprehensible presentation. Received January 2000 References Azar, B. 1989. Understanding and Using English Grammar. (2nd edn.). Englewood Cli¤s, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. Bolinger, D. 1968. ‘Entailment and the meaning of structures’. Glossa 2/2: 119–27. Celce-Murcia, M. and D. Larsen-Freeman. 1983. The Grammar Book: An ESL/EFL Teacher’s Course. Rowley, Massachusetts: Newbury. Eastwood, J. 1994. Oxford Guide to English Grammar. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Emonds, J. 1972. ‘A reformulation of certain syntactic transformations’ in S. Peters (ed.). Hofmann, T. 1966. ‘Past tense replacement and the English modal system’. Harvard Computational Laboratory, NSF Report 17. Horn, G. 1975. ‘On the nonsentential nature of the POSS-ING construction’. Linguistic Analysis 1: 333–87. Householder, F. 1964. Some Classes of Verbs in English. Bloomington: Indiana University Linguistics Club. Murphy, R. 1994. English Grammar in Use (2nd edn.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Peters, S. (ed.). 1972. Goals of Linguistic Theory. Englewood Cli¤s, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall. Quirk, R., S. Greenbaum, G. Leech, and J. Svartvik. 1972. A Grammar of Contemporary English. London: Longman. Thomson, A. and A. Martinet. 1986. A Practical English Grammar. (4th edn.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. The author Walter Petrovitz is Associate Professor ESL at St. John’s University in New York City. He completed his doctoral work in linguistics at the City University of New York. His publications include work in both theoretical linguistics and secondlanguage pedagogy. His current research interests focus on the ways in which semantics and discourse analysis can be used in the teaching of grammar. Email: [email protected] The sequencing of verbal-complement structures articles 177 welcome