* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Planning Nutritious Diets

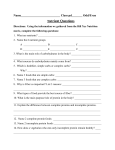

Survey

Document related concepts

Organic food wikipedia , lookup

Low-carbohydrate diet wikipedia , lookup

Food safety wikipedia , lookup

Overeaters Anonymous wikipedia , lookup

Diet-induced obesity model wikipedia , lookup

Obesity and the environment wikipedia , lookup

Saturated fat and cardiovascular disease wikipedia , lookup

Food studies wikipedia , lookup

Food politics wikipedia , lookup

Food coloring wikipedia , lookup

Human nutrition wikipedia , lookup

Childhood obesity in Australia wikipedia , lookup

Transcript