* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download An Introduction to Foods, Nutrients, and Human Health

Low-carbohydrate diet wikipedia , lookup

Dietary fiber wikipedia , lookup

Food and drink prohibitions wikipedia , lookup

Abdominal obesity wikipedia , lookup

Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics wikipedia , lookup

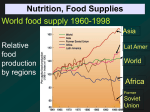

Malnutrition wikipedia , lookup

Vegetarianism wikipedia , lookup

Overeaters Anonymous wikipedia , lookup

Diet-induced obesity model wikipedia , lookup

Food studies wikipedia , lookup

Saturated fat and cardiovascular disease wikipedia , lookup

Food coloring wikipedia , lookup

Food politics wikipedia , lookup

Obesity and the environment wikipedia , lookup

Human nutrition wikipedia , lookup

Food choice wikipedia , lookup