* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

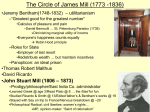

Download jeremy bentham and gary becker: utilitarianism and economic

Ecological economics wikipedia , lookup

Philosophy of history wikipedia , lookup

Steady-state economy wikipedia , lookup

Social Bonding and Nurture Kinship wikipedia , lookup

Criminology wikipedia , lookup

Peace economics wikipedia , lookup

Community development wikipedia , lookup

Neohumanism wikipedia , lookup

Environmental determinism wikipedia , lookup

Economic anthropology wikipedia , lookup

Psychological egoism wikipedia , lookup

Schools of economic thought wikipedia , lookup

History of economic thought wikipedia , lookup

Home economics wikipedia , lookup

Public choice wikipedia , lookup

History of the social sciences wikipedia , lookup

Development theory wikipedia , lookup

Anthropology of development wikipedia , lookup

Postdevelopment theory wikipedia , lookup

Neuroeconomics wikipedia , lookup

Development economics wikipedia , lookup