* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Verbs and verb tenses

Sanskrit grammar wikipedia , lookup

Old Irish grammar wikipedia , lookup

French grammar wikipedia , lookup

Modern Hebrew grammar wikipedia , lookup

Proto-Indo-European verbs wikipedia , lookup

Lexical semantics wikipedia , lookup

Navajo grammar wikipedia , lookup

Germanic weak verb wikipedia , lookup

Georgian grammar wikipedia , lookup

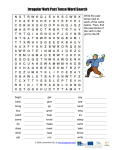

Esperanto grammar wikipedia , lookup

Scottish Gaelic grammar wikipedia , lookup

Old Norse morphology wikipedia , lookup

Udmurt grammar wikipedia , lookup

Old English grammar wikipedia , lookup

Spanish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Germanic strong verb wikipedia , lookup

Ukrainian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Macedonian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Kannada grammar wikipedia , lookup

Future tense wikipedia , lookup

Italian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Pipil grammar wikipedia , lookup

Portuguese grammar wikipedia , lookup

Hungarian verbs wikipedia , lookup

Lithuanian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Latin conjugation wikipedia , lookup

Swedish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Ancient Greek grammar wikipedia , lookup

Tense–aspect–mood wikipedia , lookup

Serbo-Croatian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Yiddish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Polish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Continuous and progressive aspects wikipedia , lookup

English clause syntax wikipedia , lookup

Latin syntax wikipedia , lookup

Chichewa tenses wikipedia , lookup

German verbs wikipedia , lookup

English verbs wikipedia , lookup

1 SUPPLEMENTARY READING: VERBS AND VERB TENSES Introduction This supplementary reading is a basic introduction to the subject. Some of you may already know quite a lot about the English tenses, but what you know will depend on your background (your previous education and reading, for example). Some graduate students might already be teachers of English and have a strong grasp of the English tense system. If so, you will find this reading easy. You may, however, find that there are slight differences in terminology from what you are used to, and this reading may refresh your memory of some points as well as prepare you for some of the special features of Hallidayan linguistics with respect to tense and aspect. You may be surprised to see that, although there is quite a lot about verbs and verbal groups in The Functional Analysis of English, there is very little specifically about tenses. We hope that this reading will partly fill the gap. We have attached three appendices to this supplementary reading: (1) a list of the main tenses in English in the active voice; (2) a list of the verb forms in English in the passive voice; and (3) some notes on irregular verbs in English. You may find these useful for reference. Tense and aspect We usually refer to tenses by names that incorporate aspect, such as the present continuous tense, where ‘present’ refers to time and ‘continuous’ refers to aspect. Tense is the grammatical category relating to time (past, present and future) and aspect is the category used for reference to other temporal features, such as whether an event or process extends over a period (known as progressive or continuous aspect). The other main aspect for which there is a term in English is perfect, used most often for a state resulting from an event that happened earlier than the moment of speaking or before another stated event in the past. 2 I have just finished reading David Copperfield. We have already seen the pyramids. The stranger’s clothes were dusty and muddy, as if he had travelled a long way. Some languages have specific means of expressing a wide variety of aspects. In English we can express these aspects, but certain tenses can express more than one aspect and these are not recognized in their names. For example, the past simple tense can be used for an event that is considered by the speaker to have been the case for a long period of time in the past (Shakespeare lived from 1569 to 1613), or for a single completed event in the past (‘You killed my grandmother!’ cried little Claus) or for a series of repeated events in the past (Every day, she danced and every evening, he told her a story). Halliday incorporates aspect in his system network for FINITENESS. Here we reproduce the section relating to participles, the next section of this reading: Infinitives and participles There are three types of non-finite verb in English and each can be used with Finite auxiliaries to make a tense. They are infinitives, present participles (often known as the -ing form) and past participles (often known as the -en form). 3 All present participles end in -ing, but most past participles end in -ed and only some irregular verbs have participles that end in -en; for example been, seen, eaten. -en is the chosen form to avoid confusion with the past simple tense, which also usually ends in -ed. (See Appendix III for more examples of irregular verbs.) The infinitive is the form of the verb that is listed in a dictionary. In a clause it may form part of a verb group, where it may follow a modal operator (as in will go, can play, etc.): We will tie a rope around your waist, and then he can pull you up again. An infinitive can also be used with the preposition to as in the following example: The soldier bought some new clothes to wear at the wedding. The -ing form (e.g. playing, thinking, speaking) is used with a finite operator and sometimes other auxiliaries to form the progressive (continuous) tenses. Notice that although it is called the present participle, it is used in both present, past and future continuous verbs: The nightingales are singing near the Convent of the Sacred Heart. Little Claus was crying as he walked through the dark wood. I will be teaching my son to wash, iron and darn. When it is not used as part of a tense, the -ing form can function as a non-finite verb, stand alone to form the head of a nominal group (a gerund), or modify a noun, as in the following examples: Beating a kettle drum, the old man led the way. (non-finite verb, realizing a material process) They couldn’t tell when the singing came to an end. (nominal group, Subject of came) Birthday fireworks lit up the faces of the marching protesters. (Epithet, modifying protesters) 4 The past participle (-en form) is used to construct the perfect tenses when combined with the verb have as operator (as in I have finished, He has lost, They hadn’t eaten, etc.). In addition to its place in the perfective forms of the verb, the past participle combines with forms of the verb be in the passive, which can exist in any tense (as in It was trapped, We had been educated, They will not be admitted). Like the -ing form, it can also function as a non-finite verb, stand as a head of a nominal group, and modify a noun: Held in custody for five and a half years, the banker was yesterday granted a final appeal by the High Court. (non-finite verb, realizing a material process) There is evidence of contact between the accused and the victim. (nominal group, in this example linked with another nominal group) Another half-hour’s walk brings us to the deserted village of Holyoak. (Epithet, modifying village) Halliday’s approach to tense Generally, in An Introduction to Functional Grammar (IFG), Halliday refers to the English tenses by the same names as those used by most modern grammarians and teachers of English. These are the names used in the Table of English verb tenses at the end of this reading (Appendix I). However, Halliday develops the account of verb tenses in two major ways. The first can be found in Chapter 4 of IFG, where he introduces the terms primary tense and secondary tense to describe different parts of the verbal group. The term primary tense is used for the tense of the Finite operator, which he sees as indicating ‘past, present or future at the moment of speaking’ or ‘time relative to “now”’. The secondary tenses are carried by any auxiliaries in addition to the Finite. Thus, what is known as the future perfect tense (e.g. will have worked) is re-analyzed as follows: primary tense secondary tenses 5 will have worked In the next example, we have an even longer verbal group: By tomorrow, I will have been working in Hong Kong for four years. The analysis, slightly simplified would be: primary tense secondary tenses will have been working Future present past present The meaning behind this is that will projects a point of time in the future in relation to the time of speaking, have been (have + -en) refers to a period of time preceding that point of future time, and the been working (be + -ing) suggests that the action is continuing on into that point of time in the future (named as ‘tomorrow’ at the time of speaking but which will be present by then). This type of analysis is very complex and, at the time of writing, may be largely irrelevant to most applications. It may prove to be important for the computer generation of natural language, and it plays a part in the construction of system networks in their present form. In Chapter 6, where Halliday introduces the logical structure of the verbal group, he discusses the serial nature of English tenses, claiming that it shows how the systems for TENSE allow the other auxiliary verbs to stand in relation to the Finite. This is generally considered to be a difficult area of systemic grammar so we shall not discuss it further here. It will, no doubt, be the subject of future research (see, for example, Fawcett 2013). Some thoughts on the naming of tenses Whatever model of linguistics we study, from traditional school grammar to the most up to date functional lexicogrammar, there is a problem with the basic terminology of verb tenses in English. The problem is that we cannot escape from the words past, present and 6 future. These three words are normally applied to verb tenses, giving the impression that there is a definite fixed correspondence between the tense and the time it represents, which is not actually the case. Although there is a strong correspondence between tenses and time (in relation to the moment of speaking), it is not a one-to-one correspondence, and the use of tenses also varies according to register and genre. To take an extreme example, you may have noticed that historians have a strong tendency to use present tenses to relate past narratives, a characteristic many people find very annoying. However, the reality is much more complicated than that. To take a very straightforward example, consider the following: 1. We leave tomorrow for Athens. 2. We are leaving tomorrow for Athens. 3. We shall leave tomorrow for Athens. Each example (1, 2 and 3) predicts an event expected to take place on the day after the time of speaking, that is in the future from the speaker’s viewpoint, yet each uses a different tense. The tense in (1) is called the present simple, the tense in (2) is the present progressive (sometimes called the present continuous) and the tense in (3) is usually called the future tense, even though it is actually constructed with a modal verb (will) and an infinitive (leave). The time is simply indicated by the adjunct tomorrow. Contextually, each example might seem more appropriate in certain circumstances, but this is irrelevant to the fact that only in the case of (3) does the name of the tense match the time of the event. To take another example, consider some of the various meanings that can be given to the same tense, in this case, the present simple: 4. The year depends only on the time the earth takes to travel round the sun. 5. The world’s greatest sports people compete in the Olympic Games. 7 6. I promise that I will do my best to do my duty to God and to Australia ... In (4) the two verbs in the present simple tense (depends, takes) are used for happenings that are considered to be the case yesterday, today and in the future as far as we can see without ceasing as long as the solar system in its present form continues. In (5), the present simple tense (compete) is used for a variety of events that happen from time to time, in the past and (possibly) the present and (we expect) in the future, but not continuously. In (6), part of the Australian Boy Scouts’ promise, the tense in the verb promise is used for a single process taking place at the moment of speaking (‘now’ from the point of view of the speaker). As we have seen above, in certain situations the present simple tense can also be used for a future event. Note that in the examples we have given it is not essential to include time adjuncts in the clause. The examples we have looked at so far concern usage and context, but even grammatically, English does not always select tense to match time, for example, in clause complexes with a dependent clause of time or condition, the dominant clause may be in the future tense, but the dependent clause will usually (but not always) be in the present even when it refers to a future time. See the following examples (present tenses with future meanings underlined): 7. When the poppies bloom again, I’ll remember you. NOT *When the poppies will bloom again, I will remember you. 8. I have guns and I will use them if I am pushed. NOT *I will use them if I will be pushed. We are not suggesting that there is any possibility of changing the names of English tenses; they are too well established, but simply that we must be aware of the complexity of the meanings that most verb tenses can express and not expect a one-to-one relation with time. 8 It may help to remember that the names of the tenses exist for purely historical reasons. They were transferred into English from the work of Latin grammarians who were describing a very different language, one where each tense used the base lexical form of the verb without auxiliaries, and indicated the tenses by the use of inflections (endings) attached to the word. From a single instance of a one-word Latin verb, you know the person, the tense, and whether it is in the active or passive voice, as well as the lexical meaning. This is not true for English. 9 APPENDIX I MAIN TENSES IN ENGLISH: ACTIVE VOICE Regular verbs SIMPLE TENSES Present Simple Past Simple I work (he/she/it works) I worked PROGRESSIVE TENSES (BE -ing) also called CONTINUOUS TENSES I am working Present Progressive you/we/they are working he/she/it is working Past Progressive I/he/she/it was working you/we/they were working PERFECT TENSES: HAVE (+ -en) Note: regular verb past participle ends in -ed Present Perfect Past Perfect I have worked you/we/they have worked he/she/it has worked I had worked you/he/she/it/they had worked PERFECT CONTINUOUS TENSES (HAVE + been + -ing) Present Perfect Progressive I have been working you/he/she/it/they have been working he/she/it has been working Past Perfect Progressive I had been working you/he/she/it/they had been working MODAL FORM (MODAL + infinitive) Examples with will (Future simple) I shall/will work (Future progressive) I will be working (Future perfect progressive) I will have been working (Future perfect) I will have worked 10 APPENDIX II MAIN VERB FORMS IN ENGLISH: PASSIVE VOICE: REGULAR VERBS The form of the passive voice consists of: The appropriate tense of the verb ‘BE’ + the past participle of a transitive lexical verb Examples: Tense Active voice Passive voice PRESENT SIMPLE We play tennis Tennis is played PAST SIMPLE We played tennis Tennis was played PRESENT CONTINUOUS He is playing tennis Tennis is being played PAST CONTINUOUS He was playing tennis Tennis was being played PRESENT PERFECT We have played tennis Tennis has been played PAST PERFECT We had played tennis Tennis had been played MODAL FORMS We will play tennis Tennis will be played I might play tennis Tennis might be played They may be playing tennis Tennis may be being played She must have played tennis Tennis must have been played Note: The passive voice also appears in non-finite forms. See the following examples: 1. She enjoyed being taught a foreign language. (Compare: She enjoyed teaching it to others.) 2. The Professor wanted the essay to be finished by Friday. (Compare: The Professor wanted to finish the essay by Friday.) 11 APPENDIX III COMMON IRREGULAR VERBS Note 1: Many verbs in English are irregular. Here we offer a sample, placed in groups of similar types. A complete list can be found in some learners’ dictionaries. Note 2: The present tense is not mentioned in these lists because it is the same as the infinitive except that it takes the inflexion -s after singular Subjects. Group 1 CUT – CUT In this group the simple past tense form and the past simple form are the same as the infinitive. infinitive simple past tense past participle burst burst burst cost cost cost cut cut cut hit hit hit hurt hurt hurt let let let put put put shut shut shut set set set slit slit slit read read read Note: Pronunciation difference of ‘read’ infinitive. Group 2 BUY – BOUGHT In this group the past simple tense and the past participles are the same and both end in -ght, pronounced /t/. infinitive simple past tense past participle buy bought bought bring brought brought fight fought fought seek sought sought think thought thought catch caught caught teach taught taught 12 Group 3 RING – RANG – RUNG infinitive past simple tense past participle ring rang rung sing sang sung spring sprang sprung drink drank drunk shrink shrank shrunk sink sank sunk begin began begun Group 4 BLOW – BLEW – BLOWN infinitive past simple tense past participle blow blew blown fly flew flown grow grew grown know know known throw threw thrown Note: Two similar verbs are: draw – drew – drawn see – saw – seen Group 5 This is a tiny group of two verbs. The only things they have in common are that their infinitives rhyme, and they both have past participles ending in -en. Their past simple forms are quite different from each other. Remember that in grammatical terminology the past participle form is often known as the -en form, and these verbs actually have past participles ending in -en. Other past participles ending in -en include spoken, written, smitten and bitten. infinitive past simple tenses past participle eat ate eaten beat beat beaten 13 Group 6 BEND – BENT – BENT In this group the simple past tense and the past participle are the same and they both end in the letter ‘t’. infinitive past simple tense past participle bend bent bent build built built feel felt felt keep kept kept leave left left light lit lit mean meant meant send sent sent spend spent spent sleep slept slept spill spilt spilt weep wept wept burn burnt burnt learn *learnt *learnt Note: *There is also an alternative regular form of this verb: learn – learned – learned