* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Standardize or Adapt? Building a Successful Brand in the Fashion

Perfect competition wikipedia , lookup

Product placement wikipedia , lookup

Marketing plan wikipedia , lookup

Direct marketing wikipedia , lookup

Market segmentation wikipedia , lookup

Guerrilla marketing wikipedia , lookup

Market penetration wikipedia , lookup

Viral marketing wikipedia , lookup

Neuromarketing wikipedia , lookup

Darknet market wikipedia , lookup

Food marketing wikipedia , lookup

Consumer behaviour wikipedia , lookup

Celebrity branding wikipedia , lookup

Street marketing wikipedia , lookup

Target audience wikipedia , lookup

Visual merchandising wikipedia , lookup

Segmenting-targeting-positioning wikipedia , lookup

Digital marketing wikipedia , lookup

Green marketing wikipedia , lookup

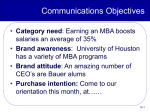

Marketing communications wikipedia , lookup

Target market wikipedia , lookup

Multicultural marketing wikipedia , lookup

Integrated marketing communications wikipedia , lookup

Marketing mix modeling wikipedia , lookup

Marketing strategy wikipedia , lookup

Marketing channel wikipedia , lookup

Youth marketing wikipedia , lookup

Product planning wikipedia , lookup

Advertising campaign wikipedia , lookup

Brand awareness wikipedia , lookup

Brand loyalty wikipedia , lookup

Global marketing wikipedia , lookup

Brand equity wikipedia , lookup

Personal branding wikipedia , lookup