* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download US History I: Semester 1

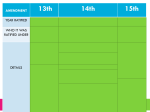

Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution wikipedia , lookup

United Kingdom and the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Commemoration of the American Civil War on postage stamps wikipedia , lookup

Border states (American Civil War) wikipedia , lookup

Union (American Civil War) wikipedia , lookup

Hampton Roads Conference wikipedia , lookup

Mississippi in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Tennessee in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

United States presidential election, 1860 wikipedia , lookup

Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution wikipedia , lookup

Issues of the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Military history of African Americans in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Reconstruction era wikipedia , lookup

Reconstruction and Its Effects The Politics of Reconstruction 11 James K. Polk 1844 Democrat 12 Zachary Taylor 1848 Whig Chapter 12 U.S. History I Section 1 Condensed Version 13 Millard Fillmore 1850 Whig 14 Franklin Pierce 1852 Democrat 15 James Buchanan 1856 Democrat pp. 376-382 16 Abraham Lincoln 1860 Republican 17 Andrew Johnson 1865 Democrat 18 Ulysses S. Grant 1868 Republican Andrew Johnson became the next president after Lincoln was assassinated. Johnson started his political career in Tennessee. He became a congressman, governor, and U.S. senator. After secession, Johnson was the only senator from a Confederate state to remain loyal to the Union. Johnson owned slaves, but later changed his mind. By 1863, he was a strong supporter of abolition. He hated wealthy Southern planters and blamed them for dragging poor whites into the war. As president, Johnson would have to decide whether to punish or forgive former Confederates and find a way to bring the Confederate states back into the Union. Lincoln’s Plan for Reconstruction Reconstruction (1865-1877) was the period after the Civil during which the United States started rebuilding. The term also refers to the way in which the U.S. government readmitted the Confederate states. This process was complicated and difficult because Abraham Lincoln, Andrew Johnson, and Congress had different ideas on how Reconstruction should be handled. LINCOLN’S TEN-PERCENT PLAN Before his death, Lincoln made it clear that he did not want to punish the Confederate states. He believed that secession was impossible because the Constitution does not allow it. Therefore, the Confederate states had never really left the Union. Lincoln felt that it was individual people, not states, who had rebelled and that as president, he had the power to forgive or pardon them. Lincoln wanted to make the South’s return to the Union as quick and easy as possible. In December 1863, President Lincoln announced his Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction, which was also known as the Ten-Percent Plan. Under this plan, the government would pardon all Confederates who promised to be loyal to the Union. High-ranking Confederate officials and those accused of crimes against prisoners of war, however, would not be forgiven. After ten percent of the voters from a state gave their oath (promise), that state could form a new state government and join Congress. Under Lincoln’s plan, four states (Arkansas, Louisiana, Tennessee, and Virginia) started moving towards readmission into the Union. Lincoln’s plan, however, angered Radical Republicans, a small number of Republicans in Congress. Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts and Representative Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania led the Radical Republicans. This group wanted to destroy the political power of former slaveholders. Most of all, they wanted African Americans to be given full citizenship and the right to vote. In 1865, the idea of giving African-Americans the right to vote was truly radical (extreme). No other country that had abolished slavery had given former slaves the right to vote. RADICAL REACTION In July 1864, the Radicals passed their own plan, the Wade-Davis Bill. This bill would put Congress in charge of Reconstruction and take the decision making away from the president. This plan also stated that a majority of voters, not just ten percent, would have to swear loyalty to the Union. Now it was up to the president to act on the bill. When a bill comes to the president, the president has ten days to either sign it into law (accept it) or veto it (reject it). In this case, however, there were less than ten days left before the end of this session of Congress. When that happens, a president can simply ignore or “pocket” the bill which then kills the bill. After Congress adjourned (ended for the time), Lincoln decided to pocket this bill. The Radical Republicans were outraged by Lincoln’s pocket veto and insisted that Congress should be in charge of Reconstruction. Johnson’s Plan After Lincoln’s assassination, Democrat Andrew Johnson was left to deal with the Reconstruction controversy (disagreement). Johnson was a firm believer in the Union and had often talked about punishing the Confederate leaders. Most white Southerners therefore considered Johnson a traitor to his region, while Radicals believed that he was one of them. As it turned out, Johnson surprised everyone with his decisions. JOHNSON CONTINUES LINCOLN’S POLICIES In May 1865, while Congress was on break, Johnson announced his own plan, Presidential Reconstruction. The new president declared that the remaining Confederate states (Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Texas) could join the Union if they met several conditions. First, each state would have to withdraw its secession. Second, each state had to swear allegiance to the Union. Third, the Confederate war debts would be erased and fourth, each state had to ratify (vote to accept) the Thirteenth Amendment, which abolished slavery. The Radicals were shocked to find out that Johnson’s plan was almost the same as Lincoln’s. The one major difference was that Johnson did not want high-ranking Confederates and wealthy Southern landowners to have the right to vote. The Radicals were especially upset that Johnson’s plan, like Lincoln’s, failed to protect former slaves on the issues of land, voting rights, and protection under the law. White Southerners, however, were happy with Johnson’s plan. They were relieved that Johnson wanted to keep the U.S. government out of individual states and allow them to govern themselves. Although Johnson supported abolition, he did not want former slaves to vote. He also pardoned more than 13,000 former Confederates because he believed that only white men should manage the South. The remaining Confederate states quickly agreed to Johnson’s terms. All the remaining states, except Texas, created new state constitutions, set up new state governments, and elected Congressmen. Some Southern states, however, did not fully comply (follow the rules) with the conditions for returning to the Union. For example, Mississippi did not ratify (vote to accept) the Thirteenth Amendment. Even though some states refused to follow al the terms, the newly elected Southern congressmen arrived in Washington in December 1865 to take their seats. Fifty-eight of the new Congressmen had been in the Congress of the Confederacy. Six of them had served in the Confederate cabinet and four had fought against the United States as Confederate generals. Johnson decided to pardon them all. Radical Republicans were furious with Johnson. African Americans felt that the government had betrayed them and had failed to mete (pass out) full justice for all African-Americans. PRESIDENTIAL RECONSTRUCTION COMES TO A STANDSTILL When the 39th Congress started in December 1865, the Radical Republicans argued that the Southern states were not much different from the way they had been before the war. As a result, Congress refused to admit the newly elected Southern legislators. At the same time, other Republicans pushed for new laws to deal with the weaknesses they saw in Johnson’s plan. In February 1866, Congress voted to continue and enlarge the Freedmen’s Bureau. Congress had originally created this organization in the last months of the war to give food and clothing to former slaves and poor whites in the South. In addition, the Freedmen’s Bureau set up more than 40 hospitals, about 4,000 schools, 61 industrial institutes, and 74 teacher training centers. CIVIL RIGHTS ACT OF 1866 In April, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1866. This new law gave African Americans citizenship and made it illegal for states to pass black codes or laws that restricted the lives of African Americans. Mississippi and South Carolina had passed black codes in 1865 and other Southern states had quickly copied them. Black codes put back in place many of the same restrictions slaves had lived with. Under black codes, blacks could not carry weapons, serve on juries, testify against whites, marry whites, and travel without permits. In some states, African Americans were forbidden to own land. In many areas, resentful whites used violence to keep blacks from improving their position in society. To many members of Congress, the passage of black codes indicated that the South had not given up the idea of keeping African Americans in bondage (slavery). President Johnson shocked everyone when he vetoed both the Freedmen’s Bureau Act and the Civil Rights Act. Johnson believed that Congress was giving too many rights to African Americans and gone past what was intended in the Constitution. These vetoes started a battle between the president and Congress. By rejecting the two acts, Johnson angered the moderate Republicans who were trying to improve his Reconstruction plan. Johnson also angered the Radicals by appearing to support Southerners who did not want to give African Americans their full rights. Congressional Reconstruction MODERATES AND RADICALS JOIN FORCES Moderate and Radical Republican factions (small groups) were so angry at Johnson’s vetoes that they decided to work together against the president. In mid-1866, Congress had enough votes to override the president and pass the Civil Rights Act. This was the first time that a major law was passed in spite of a presidential veto. In addition, Congress drafted the Fourteenth Amendment, which gave citizenship to all people born or naturalized in the United States. Everyone was entitled equal protection under the law and no state could deprive any person of life, liberty, or property. The amendment did not specifically give African Americans the vote. It did, however, declare that any state that did not allow a portion of its male citizens to vote would lose and equal percentage of its seats in Congress. Congress also wanted to ban Confederate leaders from holding government positions unless Congress gave them permission to do so. Congress adopted the Fourteenth Amendment and sent it to the states for approval. President Johnson, however, believed that the amendment treated former Confederate leaders too harshly and that it was wrong to force states to accept an amendment they had not created. President Johnson advised Southern states to reject the amendment. All but Tennessee did reject it, and the amendment was not ratified until 1868. 1866 CONGRESSIONAL ELECTIONS The question of who should control Reconstruction became one of the main issues in the 1866 elections for Congress. Johnson, accompanied by General Ulysses S. Grant, went on a speaking tour to try and convince voters to elect the kind of representatives who would support his plan. His train trip, however, was a disaster. Johnson offended many voters with his rough language and behavior. His audiences responded by booing him and cheering Grant. In addition, race riots in Tennessee and Louisiana caused the deaths of at least 80 African Americans. Such violence convinced Northern voters that the federal government must step in to protect former slaves. In the 1866 elections, moderate and Radical Republicans won a landslide victory over Democrats. The Republicans gained a two-thirds majority in Congress, which was enough votes to override any presidential vetoes. RECONSTRUCTION ACT OF 1867 Radicals and moderates joined in passing the Reconstruction Act of 1867, which did not recognize state governments (except Tennessee) formed under the Lincoln and Johnson plans. The act divided the other ten former Confederate states into five military areas, each under the command of a Union general. The voters in the district, including African-American men, would start again and create a new state constitution and government. To be allowed in the Union, a state had to give AfricanAmericans the right to vote and ratify the Fourteenth Amendment. Johnson vetoed the Reconstruction Act of 1867 because he thought it was unconstitutional and Congress quickly overrode his veto. JOHNSON IMPEACHED Radical leaders felt President Johnson was using his power to sabotage the Reconstruction Act. For example, Johnson fired military officers who tried to enforce the act. The Radicals looked for a reason to impeach (formally charge the president with misconduct) the president. Only the House of Representatives has the power to impeach federal officials. The Senate then holds a trial to decide if the person is guilty or innocent. When Johnson fired Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, the Radicals brought 11 charges of impeachment against him. Most of the charges were based on the Tenure of Office Act, which states that a president cannot remove an officer who already had the position without the consent of Congress. Johnson’s trial before the Senate took place from March to May 1868. In the end, the Senate was one vote short (35-19) for the two-thirds majority they needed to convict Johnson. ULYSSES S. GRANT ELECTED The Democrats knew that they could not win the 1868 presidential election with Johnson, so they nominated the wartime governor of New York, Horatio Seymour. The Republicans nominated the Civil War hero Ulysses S. Grant to run against Seymour. In November, Grant won the presidency by a wide margin in the Electoral College. The popular vote of almost 6 million people, however, was not as clear. Grant won the popular vote, but only by a margin of 306,592 votes. About half a million Southern African Americans voted, most of them for Grant. This showed everyone just how important the African-American votes could be for the Republican Party. After the election, the Radicals were afraid that former Confederates would try and find a way to stop African-Americans from voting. The Fifteenth Amendment was introduced, which states that no one can be denied the right to vote based on race, color, or past slavery. This amendment would also affect many of the Northern states that also denied African-Americans the right to vote. The Fifteenth Amendment, which was ratified by the states in 1870, was an important victory for the Radicals. Some Southern governments refused to enforce the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, and some white Southerners used violence to prevent African Americans from voting. As a result, Congress passed the Enforcement Act of 1870, which gave the federal government more power to punish those who tried to deny African Americans their rights.