* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download LIGHT Hits the Liver

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

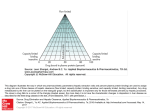

PERSPECTIVES MEDICINE An inflammatory molecule on the surface of certain immune cells increases the concentration in blood of fats associated with atherosclerosis. LIGHT Hits the Liver Göran K. Hansson A The author is in the Department of Medicine and Center for Molecular Medicine, Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, SE-17176, Sweden. E-mail: [email protected] 206 LIVER T CELL Triglycerides LIGHT Very-low-density lipoproteins Fatty acids Intermediatedensity lipoproteins Hepatic lipase Chylomicron remnant Low-density lipoproteins INTESTINE ARTERY Downloaded from on February 20, 2016 Fatty acids Chylomicron Atherosclerosis Lipolysis in the liver. Lipoproteins called chylomicrons and very-low-density lipoproteins transport triglycerides and cholesterol in the blood. Hepatic lipase assists in the receptor-mediated uptake of these lipoproteins into the liver. Triglycerides are hydrolyzed, releasing free fatty acids. Remaining very-low-density lipoproteins can be converted into low-density lipoproteins that accumulate in arteries and initiate atherosclerosis. T cells expressing LIGHT inhibit hepatic lipase expression in hepatocytes, which causes increased plasma lipoprotein concentrations, and may contribute to atherosclerosis. OX40L, are involved in atherosclerosis, and seem to propagate plaque inflammation (7, 8). In contrast to tumor necrosis factor, LIGHT is mainly expressed on the surface of T cells and specialized cells of the immune system called dendritic cells (9). Lo et al. observed that transgenic mice engineered to overexpress LIGHT on T cells developed hyperlipidemia, displaying elevated cholesterol and triglyceride concentrations in the blood. When T cells from such mice were transferred into normal mice, plasma cholesterol concentration increased substantially. LIGHT (and lymphotoxin) bind to the lymphotoxin β receptor but also to other receptors. By treating mice with soluble forms of the receptor, to function as “decoys,” the authors establish that the hyperlipidemic effect of LIGHT depends on the lymphotoxin β receptor. At first glance, it is remarkable that a cell surface molecule expressed by T cells has such dramatic effects on plasma lipids and lipoproteins. However, other links between cellular immunity and lipid homeostasis have been uncovered. In atherosclerosis, T cells of the T helper 1 subtype are activated by lipoproteins trapped in plaques on artery walls, thus promoting inflammation (10). Natural killer T cells, a subset of T cells, recognize lipids 13 APRIL 2007 VOL 316 SCIENCE Published by AAAS that are displayed in a complex with CD1 molecules on the surface of antigen-presenting cells (11). These T cells accelerate atherosclerosis (12) and are enriched in the liver. In the Lo et al. study, treatment with soluble lymphotoxin β receptor did not affect plasma cholesterol concentration in mice lacking functional natural killer T cells. This subset of T cells may conceivably regulate lipid homeostasis by delivering LIGHT to the liver (see the figure). The molecular mechanism by which the lymphotoxin β receptor causes hyperlipidemia was explored by gene-expression arrays. Lo et al. found a dramatic, 20-fold decrease in messenger RNA that encodes the enzyme hepatic lipase in the liver of transgenic mice that overexpress LIGHT on T cells. Hepatic lipase activity was also reduced in such mice, but not in transgenic mice that overexpress LIGHT but lack the lymphotoxin β receptor. When normal hepatocytes were exposed to recombinant LIGHT or to T cells overexpressing LIGHT, hepatic lipase expression dropped substantially. Hepatic lipase is expressed on the surface of hepatocytes in the liver. It promotes the receptor-mediated uptake of plasma lipoproteins that harbor triglycerides and cholesterol and specif- www.sciencemag.org CREDIT: P. HUEY/SCIENCE therosclerosis, the underlying cause of most cases of myocardial infarction, stroke, and gangrene, is the most common lethal disease in Western societies and is expected to become the number one killer globally by 2020 (1). It is an inflammatory disease triggered by the accumulation of plasma lipoproteins in the artery wall (2). In this scenario, lipids cause inflammation. However, a report by Lo et al. on page 285 in this issue (3) turns the situation upside-down by showing that two factors produced by immune cells—the cytokines lymphotoxin and LIGHT—cause the amount of lipids in the blood to increase. Several studies have implicated the tumor necrosis factor superfamily of proinflammatory cytokines in lipid metabolism. Tumor necrosis factor was discovered not only as a soluble protein that induces the death of tumor cells but also as a molecule (cachectin) that causes hypertriglyceridemia and wasting of muscle and fat tissue (4). These effects are due to its inhibition of the enzyme lipoprotein lipase, thus limiting the supply of fatty acids for energy production and fat storage. These remarkable metabolic effects of this cytokine did not attract as much attention as its proinflammatory actions and its ability to promote cell death. However, recent findings of tumor necrosis factor secretion from adipose tissue of individuals with metabolic syndrome, a condition predisposing to atherosclerosis, have focused much interest on the metabolic action of this cytokine and its cousins (5). Several of the more than 40 members of the tumor necrosis factor superfamily of proinflammatory molecules are soluble cytokines; others are membrane proteins that can ligate receptors on adjacent cells. There is substantial cross-talk between receptors and ligands. Two members of this family, lymphotoxin and LIGHT, share many features with tumor necrosis factor (the prototypic family member), such as promoting inflammation and host defense against pathogens, and they have been implicated in several inflammatory diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis and Crohn’s disease (6). Two other superfamily members, CD40 and PERSPECTIVES ically catalyzes hydrolysis of the triglycerides (13) (see the figure). Both these actions likely contribute to the reduction in the amounts of plasma lipids and lipoproteins observed when LIGHT signaling is blocked by treatment with soluble lymphotoxin β receptor. The functional role of T cell–dependent control of lipid homeostasis through hepatic lipase is unclear. Perhaps inhibition of lipolysis reduces the amount of energy-rich compounds available to pathogens and/or redistribute fatty acids to other organs during host defense. Studies of infections in mice lacking the LIGHT–lymphotoxin β receptor–hepatic lipase axis may provide interesting answers to these questions. Lo et al. suggest the exciting prospect that increasing hepatic lipase expression with agents that modulate LIGHT signaling may represent a new therapy for treating of dyslipidemia. It is even possible that inhibition of signaling by the lymphotoxin β receptor could dampen atherosclerosis by improving lipid metabolism as well as by reducing vascular inflammation. In humans, low hepatic lipase activity is associated with increased risk for atherosclerotic heart disease (14). However, proatherogenic as well as antiatherogenic effects of hepatic lipase have been observed, both in humans and in experimental animal models, and its biology is not yet fully understood (13). Further studies on the metabolic and cardiovascular actions of lymphotoxin, LIGHT, and related family members are awaited with great interest. References 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. C. J. Murray, A. D. Lopez, Lancet 349, 1436 (1997). G. K. Hansson, N. Engl. J. Med. 352, 1685 (2005). J. C. Lo et al., Science 316, 285 (2007). B. Beutler, A. Cerami, Nature 320, 584 (1986). G. S. Hotamisligil, Nature 444, 860 (2006). T. Hehlgans, K. Pfeffer, Immunology 115, 1 (2005). F. Mach, U. Schönbeck, G. K. Sukhova, E. Atkinson, P. Libby, Nature 394, 200 (1998). X. Wang et al., Nat. Genet. 37, 365 (2005). K. Schneider, K. G. Potter, C. F. Ware, Immunol. Rev. 202, 49 (2004). S. Stemme et al., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 3893 (1995). A. Bendelac, P. B. Savage, L. Teyton, Annu. Rev. Immunol. 202, 49 (2006) E. Tupin et al., J. Exp. Med. 199, 417 (2004). S. Santamarina-Fojo, H. Gonzalez-Navarro, L. Freeman, E. Wagner, Z. Nong, Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 24, 1750 (2004). K. A. Dugi et al., Circulation 104, 3057 (2001). 10.1126/science.1142238 CHEMISTRY Femtosecond Lasers for Molecular Measurements Ultrafast spectroscopic techniques are finding new applications in molecular detection. Robert P. Lucht hemists and biomedical researchers are now using femtosecond lasers to detect and measure molecules in an increasing number of experiments (1–4). This is driven by the commercial availability of reliable laser systems with pulse lengths on the order of 100 fs, fast repetition rates, and high energy in each pulse. Taking advantage of methods for producing a wide range of photon wavelengths, researchers can now expand their use of sophisticated spectroscopic detection techniques. On page 265 of this issue, Pestov et al. (5) report the detection of Bacillus subtilis spores (a surrogate for anthrax). In doing so, the authors have not only targeted a substance of vital interest but have advanced the wider use of femtosecond spectroscopy for rapid and selective detection. One of the most powerful techniques for molecular detection is coherent anti-Stokes Raman spectroscopy (CARS). In this method, depicted schematically in the figure, two laser pulses (historically called the pump and Stokes pulses) create a coherent excitation of molecules (called the Raman coherence) in the sample at time t0. A third probe pulse interacts with this coherent state at time t1, creating a signal (the anti-Stokes pulse) that can be C The author is in the School of Mechanical Engineering, Purdue University, 585 Purdue Mall, West Lafayette, IN 47907–2088, USA. E-mail: [email protected] used to map out the molecular resonances that identify a particular chemical species. Spectroscopists have used CARS with nanosecond lasers for decades (6). Typically, the technique relies on pulsed lasers with repetition rates of 10 Hz. Femtosecond laser systems offer the potential for drastic improvements in the capabilities of CARS diagnostic systems. Data acqusition rates of 1 kHz or greater can be achieved, provided that a CARS signal can be acquired with every laser pulse. Femtosecond laser systems also offer the potential to minimize the nonresonant back- ground and eliminate the effects of molecular collisions on CARS signal generation. Pestov et al. describe a hybrid CARS technique in which a 50-fs pump and Stokes pulses are used to induce a Raman coherence in a target molecule. A “shaped” probe pulse is used that has a much narrower bandwidth and, consequently, a much longer pulse length. As discussed by Pestov et al., the Fourier-transform-limited pump and Stokes pulses (that is, minimum duration for their spectral bandwidth) are optimal for excitation of the Raman coherence. In terms of probing Pump beam 675 nm, 200 cm–1 E E E Ωpump ΩStokes Ωprobe ΩCARS 2330 cm–1 E 2330 cm –1 2330 cm–1 2330 cm–1 E G G t0 t1 G G G Stokes beam A coherent picture. (Left) Creation of the Raman 800 nm, 200 cm–1 coherence at time t0 and scattering of the probe Optical frequency beam to generate the CARS signal at t1. (Right) Schematic illustration of the pump-Stokes frequency pairs that contribute to the excitation of the Raman coherence for Q-branch transitions in the 2330 cm–1 vibrational band of N2. www.sciencemag.org SCIENCE VOL 316 Published by AAAS 13 APRIL 2007 207 LIGHT Hits the Liver Göran K. Hansson Science 316, 206 (2007); DOI: 10.1126/science.1142238 This copy is for your personal, non-commercial use only. If you wish to distribute this article to others, you can order high-quality copies for your colleagues, clients, or customers by clicking here. The following resources related to this article are available online at www.sciencemag.org (this information is current as of February 20, 2016 ): Updated information and services, including high-resolution figures, can be found in the online version of this article at: /content/316/5822/206.full.html A list of selected additional articles on the Science Web sites related to this article can be found at: /content/316/5822/206.full.html#related This article cites 14 articles, 5 of which can be accessed free: /content/316/5822/206.full.html#ref-list-1 This article has been cited by 5 article(s) on the ISI Web of Science This article has been cited by 1 articles hosted by HighWire Press; see: /content/316/5822/206.full.html#related-urls This article appears in the following subject collections: Medicine, Diseases /cgi/collection/medicine Science (print ISSN 0036-8075; online ISSN 1095-9203) is published weekly, except the last week in December, by the American Association for the Advancement of Science, 1200 New York Avenue NW, Washington, DC 20005. Copyright 2007 by the American Association for the Advancement of Science; all rights reserved. The title Science is a registered trademark of AAAS. Downloaded from on February 20, 2016 Permission to republish or repurpose articles or portions of articles can be obtained by following the guidelines here.