* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download 267 Task 1 - University of Exeter

Kannada grammar wikipedia , lookup

Swedish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Sanskrit grammar wikipedia , lookup

American Sign Language grammar wikipedia , lookup

Zulu grammar wikipedia , lookup

Ancient Greek grammar wikipedia , lookup

Portuguese grammar wikipedia , lookup

Modern Hebrew grammar wikipedia , lookup

Scottish Gaelic grammar wikipedia , lookup

Malay grammar wikipedia , lookup

Yiddish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Old English grammar wikipedia , lookup

Latin syntax wikipedia , lookup

Chinese grammar wikipedia , lookup

Arabic grammar wikipedia , lookup

Sloppy identity wikipedia , lookup

Bound variable pronoun wikipedia , lookup

Serbo-Croatian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Modern Greek grammar wikipedia , lookup

French grammar wikipedia , lookup

Polish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Sotho parts of speech wikipedia , lookup

Pipil grammar wikipedia , lookup

Esperanto grammar wikipedia , lookup

English clause syntax wikipedia , lookup

Spanish grammar wikipedia , lookup

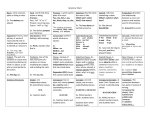

UNIVERSITY OF EXETER GRADUATE SCHOOL OF EDUCATION EFPM 267: LANGUAGE AWARENESS Task 1: Grammar Analysis Task (B) Student ID 620033084 5 November 2012 Submitted to Susan Riley 1 Introduction Relative clauses are sometimes called adjective clauses because they are used to modify nouns or pronouns. They contain relative pronouns including who, which, where, whose, when, why, and that, which act as the subject, object of a verb, or object of a preposition in the clause. (Azar, 1999:268) The concept of relative clauses can be simplified in grammars, yet their use is often more complex and difficult for students. In figure 1, I analyze a sample sentence with a relative clause. I then describe the two basic types of relative clauses before addressing aspects that can be problematic for students. The final section discusses ways this type of language analysis expands my own grammatical knowledge. Figure 1-Analysis of Main Sentence S S A C V O S V A (clause) (clause) (clause) (clause) Obj C NP NP det. The VP AdjP (postmodifier) PP (postmodifier) O NP NP VP AdvP AdjP noun prep noun relative pron pron aux. verb phrasal verb (pp) adverb verb det. adverb (submodifier) adjective noun speaker from Bristol, who nobody had heard of before, gave a really interesting talk. (Flabb, 2005) Types of Relative Clauses Indentifying Relative Clauses Indentifying clauses define which person, place, or thing is being referred to (Swan, 1996:489). They are often used to distinguish one from many. For example, in the sentence ‘My sister that lives in Virginia has a dog.’ the implication is that I have many sisters and am specifying the one that lives in Virginia. Any relative pronoun can be used in indentifying clauses, with that being used only in indentifying 2 clauses, and they do not take any addition punctuation to set them off in the sentence. These clauses are also called defining, restrictive (Swan, 1996:489), or essential relative clauses (Azar 1999:281). Non-identifying Relative Clauses Non-identifying clauses describe a person, place, or thing that is already specified (Swan, 1996:490). They do not distinguish one from many, but give more information about one that is known. For example, in figure 1, ‘The speaker from Boston’ defines who is being discussed while the relative clause ‘who nobody had heard of before’ provides additional information. Non-identifying relative clauses take any relative pronoun apart from that, and require a comma before and after to set them off in the sentence (Swan 1996:490, Azar 1999:281). These clauses are also called non-defining non-restrictive (Swan, 1996:490), or non-essential clauses (Azar 1999:281). Student Difficulties Clause Types When trying to recognize and use relative clauses, distinguishing ‘necessary’ information from ‘extra’ information can prove difficult. While it can be useful to ask if the clause specifies part of a larger group (one of many) or not, this doesn’t always give the whole picture. The ability to differentiate may be easier for students when producing their own sentences, however, it can take some time to develop when studying form and meaning in example sentences. Pronoun Choice Relative pronouns can be categorized to help students choose the correct pronoun. This creates ‘rules’ such as: who is used when talking about a person, or which is used when talking about a place or thing (Azar, 1999:268). However, it becomes more complicated as additional pronouns are included and sentences become more complex. For example, whom can be used instead of who to describe a person when acting as the object of the clause, though this is formal and possibly outdated (Chalker, 1984:252), 3 and whose is used instead of who to show possession when talking about a person (Swan, 1996:491). In addition to pronoun function in the clause, formality, and nature of the modified noun, students must also consider the type of relative clause being used, and all these factors can prove confusing. Punctuation and Clause Placement The difficulty with punctuation lies in determining if a clause is indentifying or non-identifying. However, despite the seemingly simple rules of punctuating relative clauses (i.e. no addition punctuation for identifying clauses, a comma before and after non-identifying clauses), punctuation can prove to be difficult to remember and use correctly. A relative clause usually follows directly after the noun it modifies, but determining the modified noun can be difficult for students, especially when there is more than one noun in the main sentence. In addition, these clauses are sometimes called adjective clauses, and it can be confusing that adjectives precede nouns while adjective clauses follow them. Also, as Swan points out, relative clauses can be separated from their nouns by descriptive phrases, and this can cause additional confusion. (1996:489) Inclusion of Extra Pronouns In relative clauses, the relative pronoun can act as a subject or an object, and inclusion of other pronouns in the clause depends on the function of the relative pronoun. In the sentence ‘My sister, who lives in Virginia, has a dog.’ who is the subject of the relative clause, so no other pronoun is necessary. However, in figure 1, the relative pronoun who acts as the object of the verb ‘had heard of’ and therefore a subject pronoun is needed. Determining of the role of the relative pronoun can be difficult, causing students to overuse additional pronouns in their clauses. Omission of Object Pronouns One final area of confusion is that relative pronouns acting as objects can be omitted from the clause in less formal contexts (Swan, 1996:491). For example, in the sentence, ‘The restaurant that I like is on 4 Main Street.’, the object pronoun that could be omitted, and the sentence is still correct. Yet omission does not work when the relative pronoun is the subject of the clause, and this provides one more level of complexity. Development of Personal Grammatical Awareness Language analysis tasks like this one remind me of the complexities of language forms and meanings that are so ingrained in my use of English as an L1 that I often take an understanding of them for granted. Without analyzing grammar, I am often at a loss to explain the why, when, and how of my language use, and find it difficult to illustrate the larger contextual implications of language choices. This type of analysis allows me to deconstruct complex language into smaller parts, gives me more knowledge to take into the classroom, and helps me sympathize with the difficulties of my students, anticipate areas that may be problematic, and provide more effective methods of instruction. 5 BIBLIOGRAPHY Azar, B. (1999). Understanding and Using English Grammar. (3rd ed.) White Plains, NY: Pearson Education Chalker, S. (1984). Current English Grammar. London: MacMillan Publishers. Flabb, N. (2005). Sentence Structure. (2nd ed.) London: Routledge Swan, M. (1996). Practical English Usage. (2nd ed.) Oxford: Oxford University Press 6