* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download LIQUIDS

Coordination complex wikipedia , lookup

Electronegativity wikipedia , lookup

Inorganic chemistry wikipedia , lookup

Isotopic labeling wikipedia , lookup

Acid–base reaction wikipedia , lookup

Chemical reaction wikipedia , lookup

Hydrogen-bond catalysis wikipedia , lookup

Inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry wikipedia , lookup

Electrical resistivity and conductivity wikipedia , lookup

Hydrogen bond wikipedia , lookup

Physical organic chemistry wikipedia , lookup

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy wikipedia , lookup

Bioorthogonal chemistry wikipedia , lookup

Molecular orbital diagram wikipedia , lookup

Resonance (chemistry) wikipedia , lookup

Biochemistry wikipedia , lookup

History of chemistry wikipedia , lookup

IUPAC nomenclature of inorganic chemistry 2005 wikipedia , lookup

Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry wikipedia , lookup

Extended periodic table wikipedia , lookup

Chemistry: A Volatile History wikipedia , lookup

Water splitting wikipedia , lookup

Artificial photosynthesis wikipedia , lookup

Hydrogen atom wikipedia , lookup

Molecular dynamics wikipedia , lookup

Hypervalent molecule wikipedia , lookup

Rutherford backscattering spectrometry wikipedia , lookup

Electron configuration wikipedia , lookup

Photosynthetic reaction centre wikipedia , lookup

Stoichiometry wikipedia , lookup

Electrochemistry wikipedia , lookup

Chemical bond wikipedia , lookup

Metallic bonding wikipedia , lookup

Metalloprotein wikipedia , lookup

Evolution of metal ions in biological systems wikipedia , lookup

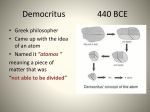

History of molecular theory wikipedia , lookup