* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download University of San Diego High School

Survey

Document related concepts

Northern Mannerism wikipedia , lookup

Art in the Protestant Reformation and Counter-Reformation wikipedia , lookup

Art in early modern Scotland wikipedia , lookup

Waddesdon Bequest wikipedia , lookup

Spanish Golden Age wikipedia , lookup

Brancacci Chapel wikipedia , lookup

Renaissance philosophy wikipedia , lookup

French Renaissance literature wikipedia , lookup

Renaissance Revival architecture wikipedia , lookup

Renaissance in Scotland wikipedia , lookup

Renaissance music wikipedia , lookup

Renaissance architecture wikipedia , lookup

Italian Renaissance wikipedia , lookup

Transcript

University of San Diego High School

Advanced Placement European History

Janet J. Davis

McKee Notes©

The Dawn of a New Era

Written by: Margaret McKee, Castilleja School, Palo Alto, California

European society in the Age of Faith--the Middle Ages, the medieval period--was

theoretically uniform in its basic institutions of feudalism and the Church. However, by

the 15th century, with tap roots going back into the 14th century, both of these institutions

faced challenges that would profoundly alter their natures. Change affected every level

and aspect of European life. Where Holy Emperor Henry IV bowed to the powerful pope,

Gregory VII, at Canossa in the 11th century, later medieval monarchs such as England's

Edward I ("the Hammer," reference Braveheart) and France's Philip IV ("the Fair" ["le bel"])

strengthened royal authority at the expense of Church and barons. Kings such as these

attempted to undermine the power of the Church as well by convening popular assemblies

such as Parliament in England, the Estates General in France, the Diets in the Holy Roman

Empire, the Cortes in Spain.

The convoking of such representative bodies attested to the growing economic and

political significance of middle classes, comprising neither the toiling serfs nor the great

feudal lords. Ambitious, resourceful kings forged alliances with the new middle class,

tapped their wealth, granted them privileges. Crown and Town sought order-peace-unity

while the barons loved to fight. In the medieval assemblies, that met only periodically and

at the king's pleasure, lords, church, and commons could lay their grievances at his feet

and hope for redress, in return for concessions of their own, usually in the form of taxes.

The king listened to complaints, administered justice, protected the people from foreign

invasion, and asked for money in order to do so.

The emergence of these more-or-less popular assemblies illustrated the new feeling of

patriotism; it also indicated the gradual erosion of Church and baronial power. Dynastic

loyalty that fostered patriotism grew at the expense of lords and Church. Fear or threats

of foreign invasion helped to define the new phenomenon. The Hundred Years War (13371454, approx.) contributed to dynastic patriotism in both England and France. The

Reconquista served the same function in Spain and Portugal. All of England rejoiced in

the victories of Crécy and Poitiers, the heroism of the Black Prince in the early phases of

the war and the triumph Henry V at Agincourt later in the war. Joan of Arc's (Jeanne

d'Arc's) martyrdom consolidated anti-English sentiments in France and led finally to the

expulsion of the English and France's unification under the Valois dynasty. The fall of the

Alhambra, the Moors' last stronghold in Granada, marked completed Spain's unification

under "Their Catholic Majesties," Ferdinand and Isabella. The latter's successes illustrate

the continuing importance of religion in the political area: Catholic Spain and Portugal

rallied against both Jews and Moors; Catholic Hungary fought against Muslim expansion;

Hussite Bohemia rebelled against the militantly Catholic Holy Roman Empire.

Other dramatic and subtle differences in attitudes and institutions distinguished the "New

Era" from the "Age of Faith" that preceded it: written and oral vernaculars challenged

Latin as the common tongue; lay mysticism and heresy (Albigensians, Hussites, Lollards)

undermined the universality of the Church as did the Great Schism of the West and the

Babylonian Captivity of the Papacy; serfs ran away and peasants rebelled (the Jacquerie

in France, Wat Tyler in England; people died in their hundreds of thousands in the

pandemic known as the Black Death. By the end of the 14th century and beginning of the

15th, people--at least the elites--had a sense of something new "in the air." They coined a

1

name for it, the Renaissance. Conventionally though incorrectly defined as a rebirth of,

variously, the arts and culture, Renaissance men (and women) turned the focus of their

attention to the Classics.

Classical studies led these individuals to examine and reexamine every field of endeavor and to change their view of themselves and of God. The

Renaissance was at least in part an attempt to reconstruct the golden age of classical

antiquity. The result was an explosion of creativity that began in Italy but spread to

encompass the continent.

Renaissance man (if such a fellow existed) lacked the historical perspective to

acknowledge his debt to medieval art, philosophy, or learning. To a certain extent, he

denounced his feudal past and ecclesiastical heritage. The early Italian humanist,

Petrarch, inveighed against the Dark Ages that separated him from the classical "age of'

light." Renaissance men were confident in their ability to make decisions, to control the

environment and understand the world. Renaissance man did not consider himself an

insignificant speck but a unique creation endowed with reason. "What a piece of work is

man," reflected Hamlet, "How noble in reason, how infinite in faculty…." Renaissance men

saw themselves at the center of God's universe, a universe they could comprehend and

perhaps refashion. Life was not the vestibule to eternity, but a place for the joy and

fulfillment that God intended for man, whom He created in His own image. A Renaissance

man lived in the world not apart from it; he was not in the cloister; he was not a priest.

The Renaissance brought man to the threshold of modern times.

The characteristic Renaissance attitude described above was known as humanism,

defined in the writings of Petrarch and Bruni. Humanism stressed the classical notion,

“Man is the measure of all things.” To quote Leon Batista Alberti, “A man can do all

things if he will.” Renaissance humanists did not question the existence of God nor doubt

the basic tenets of Christianity; however they cast such theological issues in secondary

roles:

Power, politics, creativity, individuality, ambition, success, fame absorbed

Renaissance man. He was secular and materialistic rather than spiritual and mystical.

While not denying his faith, he was simply more interested in himself. Renaissance

humanists found their role models in classical or heroic figures such as Caesar,

Alexander, Marcus Aurelius and other high achievers of the past.

Italy: Cradle of the Renaissance

The Renaissance began in Italy; from there the ideas of humanism percolated North over

the expanding trade routes. In medieval Italy the urban tradition did not atrophy

altogether, nor did the two class division of feudalism entrench itself. Trade between the

old cities of Roman times dwindled but did not die. Thus, Italy throughout the Middle

Ages, remained less rural, manorial, agrarian and insular than northern Europe. In

addition, classical ruins existed throughout the peninsula to remind man of the grandeur

of the past and to provide models for imitation. Because of the Church’s ongoing concern

with education, because of the manuscripts preserved in dusty monasteries and because

of the needs of record keeping and communication, literacy – at least for the elites –

survived.

Furthermore, the Church, with its curia, its bureaucracy, its administrative responsibilities,

needed literate clerics. It was certainly hoped that prelates above the level of parish

priests could read and write. Even in the darkest time of the Dark Ages, the Church

patronized of artists and artisans, sponsored the construction, beautification, decoration

of churches, monasteries, convents, abbeys, cathedrals. The visual arts--stained glass,

fresco, sculpture--were essential ingredients in preserving and propagating the faith

among an illiterate populace. The Church, until the Babylonian Captivity, was

headquartered in Italy (duh!).

2

Last and of enduring significance, the Crusades acted as the catalyst in the transformation

of Europe from medieval to Renaissance. For two hundred years, the crusading knights

left and returned via Venetian or Genoese ports. In the wake of the Crusaders merchants,

students, pilgrims, and tourists journeyed to and from the Holy Land. Expanding travel

and travelers introduced new products to European markets; increased demand--in

particular for the spices to preserve food or improve its taste provided incentives for

merchants to supply European consumers with their desires. Products, which in the 11th

century were priceless luxuries, by the 14th were necessities. Merchants competed for

markets, ventured farther and farther a field bringing northern Europe into the commercial,

economic, social transformation of Europe. Towns expanded, as did the flow of money

and the size of the middle class. The standard of living rose, distracting the prosperous

from matters of salvation to those of materialism. Occupations in commerce,

manufacturing, and finance attracted the ambitious. Careers were built and fortunes made

in areas completely alien to the old, medieval noble-serf stratification. These careers

demanded a facility in reading, writing and arithmetic. As men of new wealth flourished in

the new environment, they beautified their homes and places of business; they hired

artisans and artists to make them more comfortable and more luxurious. In their spare

time, these "new men" read more than their business ledgers; they purchased and

perused books from the classical past that praised the secular-rather-than-spiritual values

they espoused.

It all began in Italy. Italy's Mediterranean trade links with the Near East brought wealth to

the peninsula. Italian merchants and bankers established connections with like-minded

individuals in the North, stimulating the same kinds of developments (trade-towns-$middle class-secular p.o.v) there. Products (tallow, hides, timber, fur, leather, herring) from

the Low Countries, France, HRE, for which there were markets in both Italy and the East

found their way to new destinations. To facilitate trade, great banking houses, such as the

Medici, Pazzi, Fuggers, and Rothschilds, emerged. The developments in Italy, the location

of Florence, and the ingenuity and dynamism of the Medici family combined to make

Florence the very heart and soul of the early Renaissance. Cosimo d'Medici and his

grandson Lorenzo were among the greatest art patrons or all time!

Art and Artists of the Italian Renaissance

No better illustration of the dramatic changes occurring in Florence, Italy, and Europe can

be found than in the veritable explosion of artistic genius that took place in Renaissance Florence. Here could be seen exuberant humanism interacting with both classical ideals

and the continuing influence or a revitalized Church. Indeed, there was a clear thread of

continuity between medieval art (powerfully religious and symbolic) and the full flowering

of Renaissance humanistic art. In the Quattrocento and Cinquocento, a number of artists

in both painting and sculpture represent the interconnection of spiritual themes (religious

or Churchly subject matter, didactic in intent) and secular (new techniques and styles, new

subject matter.)

PRECURSORS

1. Giotto (1266-1337). His dates identify Giotto as an extremely early or pre-Renaissance

artist; he was the trail-blazer, groundbreaker, revolutionary who prepared the way for the

great "masters" of the Quattrocento. As a Renaissance man (or wannabe Renaissance

man,) he signed his paintings and more than dabbled in architecture and construction. In

keeping with the definitions described above, Giotto was a Florentine; his paintings were

consistently religious in both subject matter and location. He painted familiar stories from

the Old and New Testaments and lives of the saints in churches, monasteries, cathedrals,

and chapels in the traditional medium of fresco, painting on wet plaster. However, Giotto

broke entirely from the flat, symbolic disciplines of the past, portraying his figures with

weight, bulk, form, depth, realism. He discarded the characteristic style of medieval

3

miniature and illumination to give fresh rendering to traditional subjects. Today, Giotto's

frescoes may appear stilted and primitive to the modern eye, but they stunned his

contemporaries with their powerful, impact. He drew from live models rather than copying

old pictures and perpetuating old symbols. Giotto's innovations brought painting from the

cobwebbed cloisters of the medieval past into the full light of Renaissance day. His people

seemed to be composed of flesh and blood and to be experiencing real human emotions.

He defined a psychological and visual realism that pointed to an altogether new direction

in western art. Every great artist of the later periods studied his frescoes. His impact was

enormous.

2. Brunelleschi (1377-1446) Also a Florentine, Brunelleschi's important contributions lay

in the areas of painting and architecture. His major architectural achievement was the

design and construction of the dome on the Cathedral in Florence, a hugely significant

accomplishment for that day and this. In typically Renaissance fashion, his inspiration

came from the classical ruins of the Pantheon in Rome. He influenced others to

incorporate classical forms such as geometric shapes, columns, the rounded arch to

achieve the balance and harmony of' the classical and Renaissance ideals. The Pazzi

Chapel, Hospital of the Innocents, and Medici Library are all examples of Brunelleschi's

genius. In addition to being an architectural trend-setter, Brunelleschi's impact on painting

was considerable. He and other major artists of his day, such as Donatello, Ghiberti, and

the Pisano Brothers, competed to win the commission to cast the low-relief bronze

decorations on the doors to the Baptistry in Florence. Brunelleschi lost to his life-long

rival Ghiberti, but in composing his design, Brunelleschi formulated the principles of

linear perspective and three dimensions, which every artist worth his salt utilized from that

time on. Thus, Brunelleschi stands as a major early or pre-Renaissance artist in the fields

of both architecture and painting. His struggles with the Signoria and competitions with

other artists all place him in the mainstream of the Florentine Renaissance.

3. Donatello (1396-1466). The Florentine, Donatello, did for sculpture what Giotto did for

painting and Brunelleschi for architecture. His “David” was a stunningly original statue,

the first free standing nude carved since classical antiquity. “David” was revolutionary

because Donatello dared to portray him as a young Greek god; his casual nudity was

daring innovation. In “David” as well as his other works of spiritual or Biblical subjects,

Donatello worked to capture and portray reality rather than relying on worn out symbols

from the past, incorporating movement and grace into his statues. He was one of the first

artists to attempt in sculpture the fusion of the classical with the traditionally Christian:

“David” is an excellent example of a traditionally Biblical subject executed in a startling

classical or new manner. Donatello’s statues illustrated the neo-platonic ideal of the

Renaissance – that is, outer form reflects inner essence. The clarity, purity and beauty of

“David” were the outward manifestations of his essential nature. Other major works by

Donatello included “Gattamelata”, “Mary Magdalene”, “john the Baptist” and “Habbakuk”.

Donatello's innovations marked the departure of European sculpture from its medieval

antecedents. Medieval sculpture, for the most part, was columnar. Renaissance sculpture

was free-standing and three-dimensional. In addition, Renaissance sculptors after

Donatello emphasized the nude human body, which became a supreme vehicle for the

expression of beauty.

The trail-blazers--Giotto, Brunelleschi, and Donatello--were followed by the "giants" of the

Quattrocento (14001s) and the Cinquecento (1500's). In the Quattrocento, experimenting

with line, color, bulk, volume, perspective, and detail were Masaccio and Botticelli. From

this true century of genius, I have selected my two favorites.

4

QUATTROCENTO (1400's)

1. Masaccio (1401-1428). The promise of Giotto was fulfilled a century later by Masaccio.

Contemporaries immediately recognized his frescoes, especially the "Life of St. Peter" in

the Branacci Chapel, as landmarks. Every ambitious painter of the Quattrocento and after

(Fra Angelico, Fra Filippo Lippi, Botticelli, Leonardo, et al.) came to study his bold nudes,

startling use of perspective, precise attention to anatomical detail, and subtle use of light

and shadow. In Masaccio's frescoes lay the first suggestion of the heroic view of man that

would reach its climax in Michelangelo's "Creation" and "Last Judgment." Each figure in

Masaccio's "Tribute Money" emerged as a real individual occupying space and time. His

technique gave new power to the traditional Christian message, as well as a high moral

tone to his massive, austere, majestic human figures. His deep religious convictions were

powerfully evident in all of his paintings.

The viewer is immediately struck with Masaccio's conception and rendering of human will

and responsibility in the dramatic painting, "The Expulsion of Adam and Eve from the

Garden of Eden." Masaccio did not expend his artistic energies in portraying the charm,

grace, or refinement found in Donatello's neo-platonic ideal. He was not as tied to classical

idealism as were Brunelleschi and Donatello, choosing instead themes of order, power,

and a tragic view of the human struggle. Like Giotto, Masaccio prepared the visual and

psychological way for the monumental heroism of Michelangelo.

2. Boticelli (144501510). Botticelli developed a graceful, harmonious and melodic style of

painting that made exquisite use of color and clarity of line. In his two most famous

paintings, “The Birth of Venus” and “Springtime”, Botticelli demonstrates how much a

product of humanism he was, and how enamored he was with the classics and the

classical view. He freely expressed classical themes; he gave full recognition to the gods,

goddesses and myths of antiquity. He delighted in the female nude and defined a whole

new concept of feminine beauty: a graceful woman with a slender body, flowing golden

hair and an air of languid, undulating, pouting sensuality. However, even in the sunny

optimism of his Florentine youth, Botticelli hinted at an undercurrent of melancholy and

disillusionment in the Quattrocento.

Botticelli's later career coincided with the death of his great patron, Lorenzo the

Magnificent, and the traumatic rule of Savonarola in Florence. Botticelli himself

experienced a profound religious conversion and destroyed some of his beautiful

paintings in the infamous "burning of the vanities." After 1492, a new note of pessimism

and dread intruded his paintings. "Calumny" and "Pieta" reflected a brooding sense of

doom and foreboding. He abandoned the dreamy grace of the "Birth o' Venus" for an

ascetic style; despair and rejection could be seen as he recognized the unfulfilled

promises of the Florentine Renaissance. The contrast between his early and late works is

obvious and dramatic, even to the untrained eye.

CINQUOCENTO

After Botticelli, the Renaissance moved off in other directions; to a certain extent it moved

from Florence to a new flowering in Rome. The artists in the Cinquecento did so too.

Although they continued to paint and sculpt religious and classical themes, the artists of

the 1500s experimented in and with landscape, still life and portraiture. Oil was introduced

to Italy in about 1450. The great geniuses of the High Renaissance, or Cinquecento, were

Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo and Raphael. The artists showed increasing interest in

nature and form and the interplay of light and shadow. They worked to portray an essence

of man according to their own personal perceptions. Leonardo in particular departed from

the neoplatonic ideal (inner/outer harmony, fusion of the classical and Christian) to strive

not for beauty but for essence expressed through line, composition, light and shadow.

5

1. Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) Leonardo epitomized the Renaissance, humanistic

ideal of man. He was skilled in painting, sculpture, engineering, architecture, musical

composition, poetry, costume design, fortifications, natural history, anatomy: Versatile is

the adjective that best describes Leonardo, the prodigious and multi-faceted genius.

Probably the two most famous and most copied paintings in the world--"Mona Lisa" and

"The Last Supper"--were done by Leonardo. In these, as in all of his works, Leonardo

worked to capture a particular moment in time. 'The "moment" in the "Last Supper" was

when Jesus Christ announced to his disciples, "And one of -you shall betray me." To

which each answered with the shocked, "Is it I, Lord?" Leonardo perceived this painting

as a problem of emotion, composition, and impact.

As in many of his other commissions, once he had solved the problem, it no longer

interested him. His patrons had a terrible time getting Leonardo to complete anything once

he had lost interest in it. Poor Signore Giacondo never did get his hands on his wife's

portrait, "La Giaconda," more familiarly known as "Mona Lisa."

Many of Leonardo's uncompleted masterpieces hint at what a curious, enigmatic person

the artist was. His paintings were as complex as he was, as seen in the "Mona Lisa." He

labored for four years defining his image or woman--graceful, mysterious, beautiful, and,

in the last analysis, indefinable. The haunting smile of Mona Lisa replicates itself again

and again: "The Virgin o' the Rocks" the "Virgin and St. Anne," to name just two.

Leonardo represented the High Renaissance's departure from an uncritical absorption in

the classics. Leonardo wanted to copy no models, but to experience and experiment for

himself. He was an original, an innovator, no more bound by classical themes than by

Christian ones. Typically humanistic, however, Leonardo's continued to study and depict

the human body in its every facet and detail, including the grotesque, the ugly, the

macabre. His sketchbooks and drawings give eloquent testimony to this fascination.

Leonardo was not the single greatest artist of the High Renaissance, but he could rival the

greatest in any medium: Michelangelo in sculpture or Raphael in painting. In his drive,

range of interests and curiosity, no other artist could approach him. All of his completed

paintings were masterpieces of composition expressing tender beauty and effective use of

what Leonardo called “sfumato”, a smoky, mysterious technique that he employed to led

emphasis and drama to his paintings.

2. Michelangelo Buonnaroti (1475-1564). The titanic, heroic, tortured giant of' the High

Renaissance was Michelangelo. His stirring, optimistic, powerfully rendered in "David."

His vision, like that of Masaccio, was heroic, moral, beautiful, austere; for Michelangelo

the male nude remained the epitome of beauty. How different from Donatello's charming,

nonchalant, boyish "David" was Michelangelo's giant: inherent in Michelangelo's "David"

was also the inevitability of struggle and its possibility of failure; his hauntingly poignant

"Pieta" portrayed the eternal purity of the Virgin grieving over the death of her son, again

with the inescapability of human suffering . Michelangelo's humans struggled and

succeeded ("David") and struggled and failed ("The Last Judgment.") Like Masaccio,

Michelangelo rejected the harmonious, urbane, sophisticated, refined tendencies of the

Quattrocento. In his paintings of the human body ("Creation," "Last Judgment") he

focused his energy on the human form, especially that of the male nude, the lifeconfirming, life-enhancing symbol that, if anything, characterized Michelangelo. His

paintings and sculptures were robust, defiant, heroic, somehow tragic, especially his last

"Pietas" and "The Last Judgment."

Most famous for his three great masterpieces ("Creation," "David," and "The Last

Judgment,") Michelangelo also designed the dome of Bramante's basilica of St. Peter's.

Painter, architect, engineer, Michelangelo always considered himself first and foremost a

sculptor. Nevertheless, "Creation" on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, and the "Last

6

Judgment" on the wall place him in the ranks of the greatest masters of the Italian

Renaissance. On the ceiling o' the Sistine Chapel, executed in the medium of fresco,

Michelangelo told the story of' creation in nine panels; these were interspersed in

triangular sections along the sides of the ceiling with the ancestors of Christ and the giant

brooding figures of the prophets and sibyls who foretold His coming. The ceiling stands

as a dramatic fusion of classical and Christian themes. The portrayal of God the father,

and later of Christ at the "Last Judgment" contained Michelangelo's own vision and

religious statement. Christ was not a tender shepherd, but a stern judge. The sinners of

"The Last Judgment" remind one of Masaccio's Adam and Even in "The Expulsion..." As

in Botticelli's last works, Michelangelo's paintings reflected the influence of Savonarola.

Yet, Michelangelo's man, though perhaps doomed, retained his intelligence, will, and

courage; he embraced the struggle and grappled with destiny.

The equal of Leonardo in the breadth and depth of his talents, Michelangelo also designed

fortifications, studied anatomy, dissected cadavers, wrote poetry, and mastered the

principles of engineering and architecture. Though in his own mind always a sculptor,

Michelangelo's genius included most of the facets of Renaissance art. In his old age,

Michelangelo took the commission of his old schoolmate-now Pope, Leo X. He agreed to

design and superintend the construction on the dome of the basilica of St. Peter's in

Rome. The far-reaching ramifications of this commission

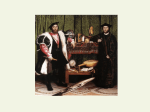

3. Raphael (1493-1520). Unlike the towering, writhing energy of Michelangelo, unlike the

unfulfilled genius of the endlessly curious and restless Leonardo, Raphael recalled the

sunny optimism of the Quattrocento paintings of Fra Angelico and Botticelli. Raphael's

world was tame, luxurious, serene, and refined. He grew up in Mantua, went to Rome in

1500 where he enjoyed the patronage of popes Julius II and Leo X, Unlike the tormented

Michelangelo who couldn't get along with anyone, Raphael was a likable fellow--neither as

intense as Michelangelo nor as complicated as Leonardo. His exquisite Sistine Madonnas

reflected his own temperament: gentle, harmonious, poetic and technically perfect. His

Madonnas revealed his highly developed sensitivity to feminine beauty, genius for

composition, and flair for visual narrative.

The influence of humanism and the classics can be seen in one of his larger works, "The

School of Athens," peopled with Aristotle, Plato, and other figures of classical antiquity,

even including the gloomy and brooding Heraclitus, apparently a figure added to the

fresco after Raphael and Bramante sneaked into the Sistine Chapel to steal a look at

Michelangelo's gargantuan epic of "Creation."

One of Raphael’s strongest talents lay in portraiture, as seen in his portraits of Julius II

and Baldassare Castiglione. Raphael was “of more limited genius…” than someone like

Leonardo, but “what he had was more fully developed.” To put it another way, Raphael

“… created little, initiated little but rather gathered into his single personality the whole

and varied activities of the men who had one before…” Raphael was a synthesizer; and

this is not intended to denigrate his rich talent in any way.

Literature of the Renaissance

Leaving the stunning art of the Italian Renaissance, one can see similar gigantic

achievements in the areas of literature, warfare, social mobility, and politics, to name just

a few. As with the visual arts, elements from the Age of faith exerted their influence, as did

the ideas of the classical revival, as did whole new attitudes and points of view. The

spiritual and secular interacted at every level. In literature in all countries, one of the major

differences from the Middle Ages lay in the departure from Latin to the local vernacular.

As early as the 14th century, Dante and Petrarch wrote in Italian, Chaucer in English. The

great mystics/heretics of the 14th century, Wyclif and Hus, delivered their sermons in

English and Czech respectively.

7

The pioneer in Renaissance literature was the Florentine, Dante (1265-1321). A

contemporary of Giotto, Dante blazed the way in writing. In The Divine Comedy, composed

in Italian, Dante fused the spiritual and the secular, Christian and classical; in this

powerful, imaginative work, Dante exemplified much of what 13th century Italians thought

about their life and their fears for the future, In The Divine Comedy, Dante and his guide,

Virgil, journey first to Hell (Inferno) then to Purgatory (Purgatorio), and finally to Heaven

(Paradisio).

Other precursors or early Renaissance writers in Italy (the cradle) such as Boccaccio

(1313-1375) and Petrarch (1304-1375) wrote in Italian, incorporated non-religious ideas in

their writings. In England Chaucer wrote The Canterbury Tales. Petrarch, a Florentine

employed in a clerical capacity for a time by the Avignon popes collected classical tomes,

which he read in their original Latin and/or Greek. A scholar of the Bible and the writings

the Church fathers, he also emerged as one the first humanists. However, his beautiful

love sonnets dedicated to Laura earned him his place in literature. Boccaccio, also a

Florentine, wrote the rich, earthy, bawdy Decameron. Set in the charming hill town of

Fiesole outside of Florence where, according to Boccaccio's whim, a number of young

Florentines gathered to escape an outbreak of plague. The bored young folk set about

telling stories to each other (like the travelers in The Canterbury Tales) to while away the

time. As in Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales, Boccaccio wrote Decameron in the

vernacular, making it accessible to the literate public,(such as it was.) It has been for

centuries a gold mine of information of what people at that time thought about, were

interested in, feared, loved, hated.

After the precursors (Dante, Petrarch, Boccaccio), the Quattrocento writers branched off

into a variety of genres. Vasari wrote a history of art and biographies of leading artists;

Leon Battista Alberti and Cellini wrote autobiographies; Lorenzo Valla (1407-1547) made a

study of the Greek, Latin, and Hebrew sources on which contemporary theology was

based, opening up the field of literary criticism. Valla's major contribution was his proof

that the "Donation of Constantine," one of the foundations of papal claims to supremacy

over Europe's kings, was an 11th century forgery.

The degree to which humanism and secularism captured the mind and enthusiasm of

Renaissance man can best be seen in the works of two Cinquecento writers, Baldassare

Castiglione (1478-1529) and Niccolo Machiavelli (1469-1527). Castiglione's fame rests on

The Courtier and Machiavelli's on The Prince. These authors eschewed religious issues

altogether and concentrated on matters of the here and now. In The Courtier, Castiglione

wrote what amounted to a manual of behavior for the accomplished Renaissance

gentleman: he must be proficient in the manly arts (riding, swordsmanship), in writing

both verse and prose, in music, in painting, in good manners and in being pleasant to "the

ladies." He should be pleasant and attractive, well-groomed, neat, and clean. He should

appear to be natural and unaffected, not conceited. He should be competent in

everything--the well-rounded Renaissance man. To a certain extent, Castiglione's

"courtier" reflected the neo-platonic ideal that inner beauty of character would reveal itself

in outer beauty of person, not unlike Donatello’s "David."

Emulating Castiglione, Giovanni Delia Casa (1503-1556) wrote Rules of Etiquette

that included the following advice to the young Renaissance gentleman:

Your conduct should not be governed by your own fancy, but in

consideration of the feelings of those whose company you keep….

When you have blown your nose, you should not open your handkerchief

and inspect it, as if pearls or rubies had dropped out of your skull. It is not

polite to scratch yourself when you are seated at table. You should also

8

take care…not to spit at mealtimes, but if you must spit, then do so in a

decent manner. It is bad manners to clean your teeth with your napkin, and

still worse to do it with your finger.

... it is not a polite habit to carry your toothpick either in your mouth like a

bird making its nest, or behind your ear.

(The Renaissance. Ed by the National Geographic Book Service, 1970, 93.)

One of the most enduringly influential writers of the Renaissance, Machiavelli addressed

issues of politics, morality, liberty, order, and the role of the state. His most famous

dictum was, "the end justifies the means." He advised a ruler to be strong and daring, as

"brave as a lion, sly as a fox." His pessimistic view of human nature, of man as a base

creature, led him to define an effective government as one that was dictatorial and could

control the low instincts of human nature. He counseled a prince to rule by fear rather

than love, to concern himself with what works rather than with what was right. He

dedicated The Prince to Cesare Borgia who, Machiavelli hoped, would unite Italy and end

the incessant civil wars that ravaged the peninsula. For Machiavelli, the unification of Italy

and establishment of order would justify any harsh or despicable tactic to achieve the

goal.

Renaissance humanists in Italy (and elsewhere) more and more concerned themselves

with problems in this world and less and less in preparation for the next. They did not

leave the Church nor did they deny its preaching; they were simply more interested in

other issues. The questions asked by humanists prepared the way for the Scientific

Awakening of the 16th and 17th centuries.

Other

Copernicus refuted the earth-centered (geocentric) view of the universe; Galileo

formulated a new methodology based upon observation and experimentation.

Bartholomieu Dias, Vasco da Gama, Christopher Columbus, Ferdinand Magellan

revolutionized not only geography, cartography, and navigation, but they transformed

man's view of himself and his world.

Observation, experimentation, and the courage to innovate produced two dramatic

technological achievements during the Renaissance: printing (casting -from movable type)

and gunpowder. Printing revolutionized intellectual life and education, bringing books

within range of more than just the extraordinarily wealthy and privileged elites; gunpowder

revolutionized warfare and made obsolete the heyday of "knights in shining armor."

Significant advances in other areas developed during the Renaissance. Leonardo, as

every schoolchild knows, was an avid student of anatomy. His drawings of the skeletal

structure, muscles, veins, and organs were startlingly accurate and illustrate the inquiring,

pragmatic side of the Renaissance. At the same time, however, Renaissance scientists

continued to be fascinated with the "pseudo-sciences" of alchemy (transforming base

metals into gold) and astrology (forecasting the future through reading the. stars,)

numerology, hermeticism. Studies in alchemy and astrology did have the beneficial result

of contributing to the development of the legitimate sciences of chemistry and astronomy.

Traditional Christianity could not emerge unchanged or indeed unscathed by the

turbulence of Renaissance thought. The Babylonian Captivity, Great Schism of the West,

Conciliar Movement, the "heresies" of Wyclif and Hus all indicated unrest with institutional

religion. Mysticism--which thrived on the borderland between orthodoxy and heresy-spread as individuals attempted to reach a personal, intimate, direct communion with God.

The profound piety that accompanied mysticism and the quest for a personal God,

9

contributed to reading and studying the Bible. Humanism and the heady wine of

individualism demanded a critical examination of sacred tests; they suggested that each

person was endowed with the capacity to understand what he/she read and could make

decisions regarding destiny and salvation. The invention of printing of course hastened

the spread of such activities. This questioning took place at a time when the Church itself

had reached a low point or prestige.

As society, attitudes, values, and relationships underwent seismic shifts, the Church

would not be immune to the challenges. Indeed, the papacy was not the same after

Avignon and The Great Schism. Three generations of exile from Rome, the pronounced

French influence, the character of the papacy during the "captivity," and its increasing

absorption with financial prerogatives diminished the devotion and affection felt towards

the Pope by the community of the faithful. The Schism further weakened the

organizational structure o' the Church.

Renaissance skepticism, individualism, criticism and questioning undermined the Church

in two ways: on the one hand, it was intellectually less satisfying to sophisticated,

worldly, secular and ambitious men who were not drawn into careers in the Church as had

been the case during the Middle Ages; on the other had, the Church was so much part and

parcel of the Italian Renaissance that the deeply devout and piously spiritual did not

percolate up into positions of power. Renaissance popes were men of the world. To put it

another way, the secularization of society was mirrored in the secularization of the

papacy. An absorption in politics, war and finance – not to mention power – filled the

College of Cardinals with appointees noted for their administrative ability and political

connections or their net worth – they had to pay for their red hats. Lorenzo d’Medici

purchased a Cardinal’s hat for his thirteen year old son, who later became Leo X, to

ensure Florentine influence in the church hierarchy. Many of the Cardinals were men of

education and benevolent patrons of literature, music, drama and art. A few of them were

saintly. Some were not yet priests; some were openly secular, for their political,

diplomatic and fiscal duties required it. Some fortified their palaces and retained private

armies (Julius II waged war with enthusiastic gusto!) for protection from the fractious

Roman mob, from condottiere and from other ambitious Cardinals.

The great majority of both laymen and clergy accepted naturally and dutifully the authority

of the Church; they believed its doctrines, obeyed its requirements, and observed the

sacraments. In considering the so-called "decline of the Church," it would be unfair and

inaccurate to deny the support and consolation it gave to vast numbers of devoted and.

devout Christians.

By the end of the 15th century, the Church and the papacy – restored to Rome for 80 years

– were deeply affected by both humanism and the easy moral laxity of the Italian

Renaissance. Violence, conspiracy, bribery and assassination were part of the political

realities of the day and hence part of the papacy of the day as well. While the Popes were

the spiritual shepherds of the faithful, they had practical responsibilities as princes of the

Papal States; as such they were embroiled in the power politics of the war torn Italian

peninsula.

10