* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Milton`s Attitude toward Knowledge in Paradise Lost

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

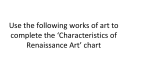

Milton’s Attitude toward Knowledge in Paradise Lost Milton’s attitude toward knowledge in Paradise Los is based on St. Augustine’s and St. Thomas Aquinas’s concepts of knowledge and ethics. In this paper, I will first point out the relevant Augustinian and Thomist concepts of knowledge and ethics, and then discuss how Milton fits them into the context of Paradise Lost. First of all, both St. Augustine and Thomas Aquinas recognize two levels of knowledge. The lower level, referring to knowledge of all contingent, ever-changing and corporeal things, is said to be attainable by human senses, while the higher level, referring to knowledge of all eternal, changeless and abstract things, is said to be supersensible and thus only attainable by means of God’s illumination or analogical interpretation. St. Augustine designates these two levels as “sense knowledge” and “contemplation knowledge,” whereas Thomas Aquinas designates them as “knowledge of the particular” and “knowledge of the universal.” Next, both St. Augustine and Thomas Aquinas approve of the pursuit of knowledge; that is why they themselves should have spent so much energy in considering things. However, St. Augustine considers it a sin to try to probe too deeply into the mysteries of the universe. So he feels himself doomed because of “intellectual arrogance.” On the other hand, Thomas Aquinas holds that every human act, including the pursuit of knowledge, should be in accordance with the order of reason. That is, the immediate end of every human act should be in harmony with the final end, which is the infinite Good, namely, God. In brief, both St. Augustine and Thomas Aquinas maintain that temperance and God’s divine order should be observed in the pursuit of knowledge. Now we come to Milton. In his Paradise Lost we clearly see that all the above-mentioned Augustinian and Thomist concepts are expressed in two episodes: Raphael’s coming to Eden to warn Adam, and Satan’s temptation to Eve. In the former episode, Milton expressed the concepts through the mouth of Raphael; in the latter, he exemplified them through the act of Eve. We know there are a series of talks between Raphael and Adam after Raphael’s arrival at Eden. However, in their talks we notice that when Adam asks about the earthly things, Raphael will answer easily and happily, but when Adam asks about the heavenly things, Raphael will answer hesitatingly and with some reserve. This makes it clear that in Paradise Lost knowledge is also divided into two levels: the earthly and the heavenly, corresponding respectively to St. Augustine’s “sense knowledge” and “contemplation knowledge,” and Aquinas’s “knowledge of the particular” and “knowledge of the universal.” The earthly things are what Adam already knows; and the heavenly things are what Adam longs to know. But the heavenly things, being abstract and supersensible, are beyond his grasp. So he needs a “Diving Interpreter” (BK. Ⅶ, 1. 72) to illuminate them. Now God has sent Raphael down as the “Divine Interpreter,” who, as we know, is said to have revealed the heavenly things to Adam on the analogy of earthly things. But while St. Augustine and Thomas Aquinas stress the importance of temperance in seeking knowledge, Raphael also perpetually emphasizes the virtue of modesty in knowledge-seeking. He even points out the bad consequence of over-curiosity to Adam, and reminds him whenever possible of the divine order. To verify the points so far suggested, there are plenty of lines we can quote. For instance, before Raphael, in answer to Adam’s request, starts relating the fall of Lucifer, he says: High matter thou injoin’st me, O prime of men, Sad task and hard, for how shall I relate To human sense th’ invisible exploits Of warring Spirits; how without remorse The ruin of so many glorious once And perfect while they stood; how last unfold The secrets of another World, perhaps Not lawful to reveal? Yet for thy good This is dispense’d and what surmounts the reach Of human sense, I shall delineate so, By lik’ning spiritual to corporal forms, As may express them best, though ... (BK. Ⅴ, ll. 563-574) Here “high matter” naturally refers to heavenly knowledge, and as such is composed of “invisible exploits,” to relate which to human sense is a “sad task and hard” for Raphael, for it “surmounts the reach/Of human sense.” So he can only delineate it by “lik’ning spiritual to corporal forms.” But he cannot delineate it all, for there may be something “not lawful to reveal.” The similar ideas are repeated before Raphael continues his recountal of the happenings after the fall of Lucifer: This also thy request with caution askt Obtain: though to recount Almighty works What words or tongue of Seraph can suffice, Or heart of man suffice to comprehend? Yet what thou canst attain, which best may serve To glorify the Maker, and infer Thee also happier, shall not be withheld Thy hearing, such Commission from above I have receiv’d, to answer thy desire Of knowledge within bounds; beyond abstain To ask, nor let thine own inventions hope Things not reveal’d, which th’ invisible King, Only Omniscient, hath supprest in Night, To none communicable in Earth or Heaven Enough is left besides to search and know. But knowledge is as food, and needs no less Her temperance over appetite, to know In measure what the mind may well contain, Oppresses else with Surfeit, and soon turns Wisdom to Folly, as Nourishment to Wind. (BK. Ⅶ, ll. 111-130) Here “Almighty works” is used instead of “high matter” to suggest heavenly knowledge. The difficulty in attaining such knowledge is suggested in the “What...?” rhetorical question. The bounds within which knowledge can be revealed to and reached by man are suggested in the next long sentence. And the bad result of intemperance in seeking knowledge is suggested in the “food” simile of the final sentence. The importance of temperance in knowledge-seeking is indeed what Raphael most intently tries to emphasize. So in every case possible, he will either directly or indirectly speak about it. After finishing his story of Creation, he says to Adam, “if else thou seek’st Aught, not surpassing human measure, say” (Bk. Ⅶ, ll. 639-640). When Adam inquires concerning celestial motions, he replies: To ask or search I blame thee not, for Heav’n Is as the Book of God before thee set, Wherein to read his wond’rous Works, and learn His seasons, Hours, or Days, or Months, or Years: This to attain, whether Heav’n move or Earth, Imports not, if thou reck’n right; the rest From Man or Angel the great Architect Did wisely to conceal, and not divulge His secrets to be scann’d by them who ought Rather admire ... (Bk. Ⅷ, ll. 66-75) He even thus exhorts Adam: Solicit not thy thoughts with matters hid, Leave them to God above, him serve and fear; Of other Creatures, as him pleases best, Wherever plac’d, let him dispose: joy thou In what he gives to thee, this Paradise And thy fair Eve: Heav’n is for thee too high To know what passes there; be lowly wise: Think only what concerns thee and thy being; Dream not of other Worlds, what Creatures there Live, in what state, condition or degree, Contented that thus far hath been reveal’d Not of earth only but of highest Heav’n. (Bk. Ⅷ, ll. 167-178) And Adam seems to have been impressed by his exhortation, for he replies that ... not to know at large of things remote From use, obscure and subtle, but to know That which before us lies in daily life, Is the prime Wisdom; what is more, is fume, Or emptiness, or fond impertinence, And renders us in things that most concern Unpractic’d, unprepar’d, and still to seek. Therefore from this high pitch let us descend A lower flight, and speak of things at hand Useful ... (Bk. Ⅷ, ll. 191-200) But as we know, although Adam has been so impressed, Eve has committed the very sin of intemperance in knowledge-seeking for succumbing to Satan’s temptation to eat the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge. We know Satan’s temptation is full of wileful arguments. He tells Eve that knowledge of good and evil can make her know how to approach good and shun evil, can thus lead her to a happier life, and can make her Gods’ equal. And Eve’s reasoning with herself, in compliance with his temptation, is that “good unknown, sure is not had, or had/And yet unknown, is as not had at all” (Bk. Ⅸ, ll. 756-757), that the eating of that fruit will not result in death since the serpent has eaten that and has not died, and that the fruit can “feed at once both Body and Mind” (Bk. Ⅸ, l. 779). In effect, Satan’s arguments only suggest some immediate ends of knowledge, to use the Thomist terms, while Eve’s reasoning is the consequence of forgetting the final end, which is the infinite Good, or God Himself. Hence, by violating the order of reason (that is, by observing the immediate ends and neglecting the final end), Eve has made sure the loss of Eden, has turned wisdom to folly. So far I have only given a few examples to illustrate my points. But I think they are more than enough to prove that in Paradise Lost Milton has indeed fully developed and clearly exemplified all my aforesaid Augustinian and Thomist concepts of knowledge and ethics through the mouth of Raphael and the conduct of Eve. Works Consulted Copleston, Frederick S. J. A History of Philosophy. Taipei: Maling Publishing Co., 1972. Jones, W. T. A History of Western Philosophy. New York: Harcourt, Brace & Co. 1952. Russell, Bertrand. History of Western Philosophy. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd., 1946.