* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download 7. Secession and Expulsion

United Kingdom and the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

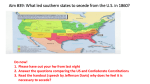

Texas in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Union (American Civil War) wikipedia , lookup

Alabama in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Baltimore riot of 1861 wikipedia , lookup

Missouri secession wikipedia , lookup

Tennessee in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Georgia in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Origins of the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

United States presidential election, 1860 wikipedia , lookup

Mississippi in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Virginia in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Border states (American Civil War) wikipedia , lookup

South Carolina in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup