* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Plant Biology: introduction to the module

Plant tolerance to herbivory wikipedia , lookup

Photosynthesis wikipedia , lookup

Plant stress measurement wikipedia , lookup

Gartons Agricultural Plant Breeders wikipedia , lookup

Plant secondary metabolism wikipedia , lookup

Plant nutrition wikipedia , lookup

Plant defense against herbivory wikipedia , lookup

Plant breeding wikipedia , lookup

Pollination wikipedia , lookup

History of botany wikipedia , lookup

Plant use of endophytic fungi in defense wikipedia , lookup

History of herbalism wikipedia , lookup

Plant physiology wikipedia , lookup

Plant morphology wikipedia , lookup

Ornamental bulbous plant wikipedia , lookup

Plant ecology wikipedia , lookup

Historia Plantarum (Theophrastus) wikipedia , lookup

Perovskia atriplicifolia wikipedia , lookup

Evolutionary history of plants wikipedia , lookup

Plant evolutionary developmental biology wikipedia , lookup

Flora of the Indian epic period wikipedia , lookup

Sustainable landscaping wikipedia , lookup

Flowering plant wikipedia , lookup

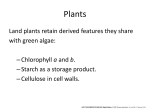

Introduction to plants All life on earth depends on plants. Without plants ecosystems would soon grind to a halt. Animals (and fungi) are parasitic on plants. Taxonomy - definitions Always start by setting out what you’re talking about! Plants are widely taken to be the green things that make flowers Kingdom Plantae – algae, mosses, ferns, conifers, flowering plants In fact the boundaries are rather unclear, especially at the single-celled level. Modern taxonomies do no try to shoehorn unicellular eukaryotes into kingdoms alongside multicellular forms but prefer to handle them as a distinct group (with 27 phyla at the last count). Within plants, the term ‘alga’ is not a monophyletic group, with red alga very different to brown and green classes. Basics Plants (like animals and fungi) are eukaryotes. Plants are primitively photosynthetic, relying on organelles called chloroplasts to capture light energy. (A few plants have lost this ability and are parasitic on other plants). Most have highly structured bodies, with green material growing upwards and roots growing down. Their cell walls are reinforced with tough polymers, notably cellulose and lignin. All are capable of sexual reproduction, and their classification is heavily based on studies of their reproductive organs. All exhibit a phenomenon called alternation of generations, which you may well be unaware of and which we will look at closely later in the lecture. In this course I will focus mainly on the familiar ‘higher’ forms, flowering plants Algae (and fungi) I will callously exclude, on grounds of time and factual overload! We will need a taxonomic structure to hang names on, so I propose to start by introducing the major taxa you need to be familiar with. I am sure that these divisions will remain valid – I am not sure that the exact taxonomic levels will remain unchanged in the next 20 years. Geological dates are also prone to being extended backwards as new fossils are found. “Each new edition of this book requires revision of most of the phylogenetic trees to reflect the ongoing revolution in systematics.”! Campbell Reece & Mitchell (1999) Biology (5th Edition) Addison Wesley (On p. 584 they show a family tree of photosynthetic eukaryotes which allows for 4 different definitions of ‘plant’!) Classification of the plants we will cover in this course. Bryophytes (mosses, liverworts) Pteridophytes Ferns and allies Gymnosperms: Conifers, cycads etc Angiosperms: Flowering plants Mesozoic 120MYBP Carboniferous 350MYBP Devonian 400MYBP Seeds Vascular tissues (tracheids or derivatives) Bryophytes These are the mosses and liverworts, both relatively common wellknown groups of non-flowering plants typical of permanently damp areas. (Actually a few specialise in dry open sites – fire sites, bare concrete etc). The dominant phase is a leafy form (the gametophyte), which is genetically different to the stalked pods that produce its spores. A typical moss, showing the spore capsule, which is a genetically different plant to the green fronds from which it grows. (More later..) The hepatica: Liverworts. These also make genetically distinct spore-dispersing individuals, but here the spores are dispersed from an umbrella-like structure, while the main plant (the gametophyte) is generally flattened, plate-like. sporophytes c. 2 cm The common liverwort Marchantia Pteridophytes: ferns, horsetails, club mosses and allies. Pteridophytes are the group of plants which first (as far as we can tell…) developed the tracheid cells which permit stems to rise high above any water supply, and as such were the first colonists of dry land, at least 400 MYBP. We have a good fossil record of them (in fact our industry has depended on burning this fossil record since the inception of the industrial revolution!). The facets which fossilise show that apart from the extinction of the giant forms, this group has changed little since the Devonian. Like mosses these plants have two genetically distinct phases in their life cycle, but here the dominant phase is the sporophyte, the familiar fern leaves etc. Ferns These are ancient but still successful forms, in which the spore-bearing stage is very familiar. Bracken Pteridium aquilinum is one of the most widespread and pernicious weeds on the planet! We still have tree ferns, native to Gondwanaland (Australasia, South America, Africa) but now widely planted in tropical, subtropical and frost-free temperate areas. In all cases spores are shed from the underside of the leaves (fronds). Bracken Pteridium aquilinum A tree fern Dicksonia antarctica Horsetails: Equisetacea These plants are every-day miracles. There are only about 15 species in the world, all in the genus Equisetum. It has changed hardly at all since the carboniferous period. I know of a Carboniferous site in Yorkshire where one can find 2m high horsetails still standing, fossilised in a cliff, looking exactly like living forms (only rather bigger, though giant horsetail E. telmateia can grow nearly this tall). Also known as Lego plants, because the stems comes apart at the nodes. Horsetails, contd. The needle-like leaves are reinforced with silica, and have been used as pan scrubs. Few animals find them palatable. For all their ancientness and oddity they are a serious weed, with immensely deep root systems and an ability to shrug off herbicides. Gardeners’ Question Time (BBC) advice on how to respond to horsetails in your garden Sell your house, in winter when the stems aren’t visible. Club mosses: Lycopodiacea These rather nondescript crawling plants are nowadays confined to a minor role in northern forests on acid soils. Present in the UK but easily overlooked. The sole survivors of a large group including vast forest-forming trees in the carboniferous, the first terrestrial forests. The have a vascular system, and always one vein running along the leaf axis. Gymnosperms This group contains many well-known plants, including all coniferous trees (pines, larch, spruce etc), yews and allies, along with other ‘living fossils’ the cycads, plus a few simple plain oddities thrown in to keep botanists happy. Gymnosperm means ‘naked seed’, and indeed in this group the fertilised seed protrudes from the cone/aril. They have apparently lost the sporophyte generation (but see later), and are now trees which shed viable seed that germinates to make a new tree – the pattern of seed germination which we are familiar with. They have tracheids allowing water to be sucked to great heights: the this group contains probably the largest (Sequoia) and oldest (Bristlecone pine, Pinus aristata) organisms in the world. UK Gymnosperms We have 3 spp native to the UK: Scots pine Pinus sylvestris, Yew Taxus baccata and Juniper Juniperus communis. Do you know where they grow? Scots pine – native to Scotland but widely naturalised on sandy acid soils Yew – dense ancient forests on southern chalk Juniper – an oddly disjunct distribution, present but under Yew on chalk and in the acid uplands. Most people know one group of gymnosperms; the conifers. Literally the cone bearers – these are pines, spruces, larches, firs etc. Cones – correctly stobili (1 strobilus) are sexual organs either shedding pollen (male cones) or bearing ovaries, awaiting fertilisation by windblown pollen (female cones). In fact all gymnosperms, plus male pine cone lycoods, have similar Female pine cone structures. You will meet the terms microsporangia (pollenproducing organs) and megasporangia (egg producing organs). Conifers Cycads These plants look rather like stunted palms, or possibly rather tough tree ferns, but are neither. They are gymnosperms that have changed little since the Jurassic period, when they were dominant land cover and presumably staple food for herbivorous dinosaurs. Now they are thinly scattered in tropical areas, some highly endangered. Males and females plants are separate, using a winddispersed pollen to fertilise their cones. The male gamete is notable for using cilia to swim towards the egg (the ‘highest’ occurrence of cilia in the plant kingdom). Some cycads fix atmospheric nitrogen using a symbiosis with blue-green algae living in their stems and roots. Ginkgo biloba – the wonderful discovery People had since the early days of fossil hunting been recovering well-preserved fossil leaves from Ancient (Jurassic and earlier) which looked like an unrolled pine needle. No living plant matched this pattern. Then in 1691 the German Engelbert Kaempfer discovered strange trees with exactly this unfamiliar leaf form in Japan, cultivated in temple gardens. They proved to be living specimens of Ginkgo, one male and one female. Thankfully their seed was fertile, and has now been widely propagated. The oldest in the UK is in Oxford botanic gardens (pruned and now rather small for its age). Generally males are planted as the female flower is rather sticky and smelly. (Sex is coded by an X-Y chromosome system, as in mammals). Welwitschia mirabilis This is certainly one of the strangest plants in the world, whose classification inside the gymnosperms has long been assumed but is confirmed by DNA analyses. It lives only in the Namib desert, South Africa, in a region where rain never falls. Instead it relies on the mist that condenses in coastal regions where cold currents from the southern oceans well up against the desert. Welwitschia has only 2 leaves, long strap-like ones that grow perpetually from their base while the ends become frayed and tatty. It is dioecious. Angiosperms: Monocotyledons and Dicotyledons Flowering plants (phylum Anthophyta) come in two fundamentally different ‘designs’ or classes, known as the Monocotyledons and Dicotyledons. Or Monocots and Dicots in botanical jargon. Formally these are defined by the number of seed leaves, or cotyledons, that emerge when the seed 1st germinates. In Monocotyledons it is 1, in Dicotyledons it is 2. Coinciding with this are a series of other characteristics which are so consistent that everyone seemed happy that these are monophyletic groups, splitting from the gymnosperms about 130 MYBP (early Cretaceous). Unifying features of monocots and dicots Class Monocotyledon Number of cotyledons1 Leaf veination parallel Flower parts in 3s Roots a fibrous bundle Stem herbaceous Arrangement of vascular bundles scattered Pollen pores 1 Dicotyledon 2 branching in 4s/5s A tap root with laterals woody in a ring 3 Monocotyledons This truly monophyletic group contains all grasses, sedges, rushes, bamboo etc. Orchids. Pineapples and allies (the bromeliads). Lilies, and their succulent relatives Aloes. Few trees but including bananas and palms. Dicotyledons. Actually the eudicotyledons plus a few others… It is here that I have to confess to a certain oversimplification. Neat though the division was, recent (late 1990s) DNA work has shown that the group known as ‘Dicots’ consists of 4 groups, all as unrelated to each other as they are to the monocots. Fortunately, virtually all the ones you are likely to meet are in a good monophyletic group, now called the Eudicotyledons. (Sometimes DNA research makes a good simple system needlessly complicated..) Eudicotyledons Here we have most gardens flowers, all herbs, cacti, climbers, and most trees. The awkward other 3 groups For sake of completeness I need to tell you of the other 3 ex-dicots. One group will be familiar and has long been thought of as primitive: the water lilies Nymphales. All are aquatic with floating leaves: Nymphaea Drimys winteri A second early offshoot is the winterales, containing Winters bark Drimys and Star Anise Illicium. Amborella trichopoda Until the Deep Green project looked at its DNA, Amborella was an incredibly obscure and unimportant member of the laurel family only found in the wild forests of New Caledonia. It turned out to be closest to the root of all flowering plants, pre-dating the split between monocots and the others. It has its own class now! Current angiosperm taxonomy. (Until they sequence something else really odd…) Eudicots Monocots Winterales Anthophyta: Water lilies Amborella Alternating generations: sporophytes and gametophytes One of the more unusual insights into plant biology comes from the study of their life cycle, specifically in a pattern of alternation that is easily seen among the ‘lower’ forms but becomes progressively less obvious as one moves from ferns to cycads to conifers and flowering plants. This pattern consists of having two genetically distinct generations, each giving rise to the other, and is called the alternation of generations. Gametophyte Sperm or eggs 0 0 Sporophyte (sheds spores) Haploid N/diploid 2N? There is one more feature to include here to understand a generalised account of the alternation of plant generations. This concerns the chromosomal composition: does the cell have 1 set of chromosomes (haploid) or two (diploid)? Where in the cycle does the crucial genetic shuffling act called meiosis occur? Gametophyte Gametophyte Haploid N + N Haploid 0 0 N Meiosis to make haploid spores Sporophyte 2N (Diploid) This alternation is clearly seen in the non-vascular plants (the non-tracheophyta), mosses and liverworts. Here we see the dominant (at least the biggest, most visually conspicuous) part of the life cycle is the sporophyte, which shed spores from various shaped capsules. The taxonomy of these plants relies largely on this phase. These spores germinate to produce a flat green individual, looking very much like a smooth lichen. This is the gametophyte, and all external gametophytes tend to look pretty much the same. There are no field guides to gametophytes, as a fern is hard to tell from a liverwort or a moss – until sporophytes appear. This pattern can be seen right up through the plant kingdom. Various modifications occur in the algae, such as the condition where the sporophyte and gametophyte look identical (until you examine their reproductive cells or count their chromosomes). This condition is called isomorphic alternation of generations. In mosses and liverworts the gametophyte thallus is the largest and most metabolically significant phase. These are most easily seen in liverworts, where the umbrella-like sporophytes sprout from an expanse of flat green thallus. In these plants the spore is the main agent of dispersal in time and space. In these plants the male gametes are motile, swimming with cilia, and can plausibly be called sperm. In Pteridophytes the gametophyte generation (haploid) is still a distinct individual (looking and behaving remarkably like a liverwort gametophyte), but this is overshadowed, both literally and metaphorically, by the much larger (diploid) sporophyte generation. Fern collectors in the UK have collected-out some rare ferns, but their gametophyte stage hung on overlooked and allowed the population to reemerge. This pattern appears to halt with the arrival of seed plants – gymnosperms and angiosperms.In fact we can see these as the extreme development of the dominance of the 2N sporophyte generation. The trick is to see the sporophyte as making a 1N gametophyte generation by meiosis which is retained as an internal individual, an egg or a pollen grain. The pollen is then dispersed, and on germination it releases a male gamete which fertilises the egg. And the sperm? In cycads the gamete is a ciliated ball which swims majestically towards the egg – elsewhere it is replaced by a simple pollen tube along which the nucleus is propelled. The alternation of generations –a summary Taxon Sporophyte 2N gametophyte N Bryophyta small capsules dominant leafy phase Pteridophyta Large leafy stage small, liverwort-like Seed plants tissue within reproductive organs Only visible phase