* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download The Team Approach to a Successful, Energized Dental Practice

Race and health wikipedia , lookup

Compartmental models in epidemiology wikipedia , lookup

Diseases of poverty wikipedia , lookup

Transmission (medicine) wikipedia , lookup

Fetal origins hypothesis wikipedia , lookup

Epidemiology of metabolic syndrome wikipedia , lookup

Eradication of infectious diseases wikipedia , lookup

Focal infection theory wikipedia , lookup

Epidemiology wikipedia , lookup

Public health genomics wikipedia , lookup

Dental emergency wikipedia , lookup

Hygiene hypothesis wikipedia , lookup

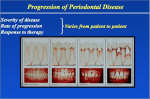

clinical Jo-Anne Jones, RDH President of RDH Connection Inc.; International Lecturer Lorne M. Golub, DMD MSc, MD (Honorary) SUNY Distinguished Professor; Department of Oral Biology and Pathology; Stony Brook School of Dental Medicine, SUNY Ying Gu, DDS, PhD Associate Professor; Department of General Dentistry; Stony Brook School of Dental Medicine Maria Emanuel Ryan, DDS, PhD Professor and Chair; Department of Oral Biology and Pathology; Stony Brook School of Dental Medicine Denis Masse, RDH Program Director; International Dental Institute Jacinthe Simard, RDH In-office Consultant; International Dental Institute 16 Is Periodontitis an Infectious or an Inflammatory Disease? T he cornerstone of the dental hygiene profession is the application of critical thinking. Critical thinking has been defined as “the use of self-correction and monitoring to judge the rationality of thinking. It is the ability to challenge one’s own thinking.”1 Consider the following question: are we treating periodontal disease as an infectious disease or as an inflammatory disease? If periodontitis is simply an infectious disease, one would assume that through the employment of judicious therapeutic measures to reduce the microbial burden at regular intervals, great inroads would have been made in the eradication of the disease. An infectious disease is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as being ‘caused by pathogenic microorganisms, such as bacteria, viruses, parasites or fungi and may be spread, directly or indirectly, from one person to another. 2 As dental professionals, we realize this is simply not the case; a recent CDC report provides the following data related to prevalence of periodontitis in the U.S.: 47.2 percent of adults aged 30 years and older have some form of periodontal disease. Periodontal Disease increases with age, 70.1 percent of adults 65 years and older have periodontal disease. 3 We now know that periodontal disease is one of the most prevalent non-communicable chronic diseases in our population, similar to cardiovascular disease and diabetes.4 We have treated dental caries as a bacterial infection and we are seeing a strong response to our therapeutic interventions. Conversely, are we achieving our therapeutic endpoints by treating periodontal disease as an infection? Mechanical debridement, employment of antimicrobials and short-term systemic antibiotic regimens, have simply not sustained the desired therapeutic endpoints we had hoped for. A meta-analysis to study the efficacy of systemic antibiotics was conducted by CunhaCruz et al. 5 and published in 2008. Historically, systemic antibiotics have been recommended for the treatment of destructive periodontal disease. However, Cunha-Cruz found a lack of association between systemic antibiotics and tooth loss in adults, coupled with the growing concerns about antibiotic resistance, reinforcing the concern that prescription of antibiotics for chronic destructive periodontal diseases should only be made with extreme caution. 5 (Note in the same statistical study, sub-antimicrobial doxycycline, i.e. Periostat, was found to be associated with decreased tooth loss.) The late 80s began to delve into the aspect of a destructive host response as a causative etiologic factor in periodontal disease. A number of landmark studies began to draw the conclusion that periodontal disease was an inflammatory disease.6 These papers, and literally hundreds of related papers, brought to the forefront the realization that it was the inflammatory response, followed by the acquired immune response, that drove the pathogenesis of periodontal tissue destruction.7 Emerging data suggests that periodontal pathogens, that are more or less universally present in low numbers, use inflammation to provide an environment to foster their growth. The implication is that the patholog- May 2015 www.oralhealthgroup.com clinical Research has shown that periodontal disease is associated with several other diseases. For a long time it was thought that bacteria was the factor that linked periodontal disease to other diseases in the body; however, more recent research demonstrates that inflammation may be responsible for the association. Therefore, treating inflammation may not only help manage periodontal diseases but may also help with the management of other chronic inflammatory conditions. Source: www.perio.org/consumer/other-diseases ic biofilm “emerges” as a result of inflammation.7 Traditional means of identifying active disease have relied upon the measurement of pocket depths, which are often indicators of past disease, and not necessarily current active disease. Therefore, the focus should be on inflammatory biomarkers in addition to longitudinal measures of CAL. The transition from infectious disease to inflammatory disease was redefined by the American Academy of Periodontology (AAP) in 2008. Today, the AAP refers to periodontitis as an inflammatory disease with far reaching destructive effects on systemic health. “For a long time, it was thought that bacteria was the factor that linked perio dontal disease to other disease in the body; however, more recent research demonstrates that inflammation may be responsible for the association. Therefore, treating inflammation (and the resultant increase in host-derived, tissue-destructive enzymes, e.g., collagenase plus other MMPs) may not only help manage periodontal diseases, but may also help with the management of other chronic inflammatory conditions.”8 Tissue Destruction Mediated by Inflammation An article published in TIME magazine, titled ‘The Secret Killer’, positions the acute inflammatory response as a lifesaver that initially enables our bodies to fend off bacterial, viral and parasitic invasions.9 The very moment any one of these intruders enter, a well-functioning immune system will react and engulf foreign invaders, aiding in con- trol of the inflammatory response. Under normal conditions, the process subsequently subsides and our bodies are then given the chance to heal. However, when in the presence of a variety of inflammatory diseases associated with periodontitis (e.g. Crohns disease, rheumatoid arthritis, CVD), this process is not “resolved”, then prolongation of the inflammation leads to destruction of the host tissues. One of the most widely studied topics of medical research today is the destruction caused by the inflammatory pathway when a transient infection becomes chronic. The very thing that will perform well with a transient infection can literally turn the body against itself when the inflammation becomes chronic. Today’s population is subjected to the attributes of a Western lifestyle, such as a diet high in sugars and saturated fats, accompanied by little or no exercise, making it far easier to sustain chronic inflammation.9 The role of chronic inflammation and its association with today’s most prevalent diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, Alzheimers, cancers, diabetes and autoimmune disorders, are well documented.10 Coronary Artery Disease (CAD) remains the number one cause of death in the world. While traditional risk factors partially account for the development of CAD, chronic inflammation has been postulated to play a role in the development and propagation of this disease. A systematic review was carried out by Roifman et al. and published in the Canadian Journal of Cardiology. The purpose of this systematic review was to determine if patients with May 2015 www.oralhealthgroup.com 17 clinical es and the increased risk of colon carcinoma. The longer the inflammation persists, the higher the risk of associated carcinogenesis.15 The chronic inflammatory states associated with infection and irritation may lead to environments that foster genomic lesions and tumor initiation.16 Figure 1. Chronic Inflammatory Process. (Acknowledgment Dr. LM Golub) Figure 2. Sub-antimicrobial Dose Doxycycline. 18 chronic inflammatory diseases have higher rates of cardiovascular disease. The results indicated that patients with chronic inflammatory conditions are at elevated risk for the development of CAD.11 Chronic inflammation is now accepted as playing a potentially important role in the promotion of atherosclerosis, a main cause of CAD.12 In this regard, chronic periodontitis is a very common chronic inflammatory disease, which is increasingly being recognized as having an association with, and a potential causal relationship to, coronary artery disease.13,14 A substantial body of evidence supports the conclusion that chronic inflammation can predispose an individual to certain types of cancer, as demonstrated by the association between chronic inflammatory bowel diseas- Treating Periodontal Disease as an Inflammatory Disease Do we really understand the far reaching destruction of inflammation on the entire body? If so, are we treating periodontal disease as it has been defined by leading authorities as an inflammatory disease? The foundational characteristics of all inflammatory diseases is the up-regulation of cytokines, prostaglandins, MMPs (i.e. hostderived, tissue-destructive matrix metalloproteinases), reactive oxygen species, etc. The only apparent difference between an inflammatory response in these diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, atherosclerosis, Crohn’s and periodontal disease, is the anatomical location. Periodontal disease is a chronic inflammatory disease resulting in alveolar bone loss. The release of excessive MMP-8 or collagenase (as well as other less prominent MMPs, i.e. MMP-13, MMP-12, plus other proteinases) is a key event in the pathogenesis of periodontal disease. Collagen forms 60 percent of the gingival tissues and the periodontal ligament. Moreover, 90 percent of the organic matrix (living part) of bone is collagen; calcium phosphate crystals are imbedded within this collagenous matrix to provide the mineral (hard) part of this tissue. The destruction of collagen in all the periodontal tissues is largely mediated by elevated MMP levels attacking the living organic matrix. A major event in the link between local periodontitis and relevant systemic/medical conditions is the release, from the inflamed periodontal tissues of inflammatory mediators into the bloodstream, which subsequently travel to the liver. The following cascade of events illustrates how chronic inflammation May 2015 www.oralhealthgroup.com clinical plays a strong etiologic role in the exacerbation of a stroke or a myocardial infarction. Once inflammatory mediators are present in the blood (i.e. derived from the inflamed gingiva), the liver is stimulated to produce acute phase proteins, which are diagnostic markers and mediators of inflammatory disease; one being C-reactive protein or CRP (Figure 1). To add insult to injury, LDL (low density lipoprotein) cholesterol, when oxidized by the inflammatory response, then forms a chemical reaction with CRP. The end result is a complex of oxidized LDL combined with CRP, which is taken up by macrophages in the atheroma. These macrophages differentiate into foam cells, which is characteristic of this lipid-laden plaque in the arteries. They are an indication of plaque build-up in atherosclerosis, which is commonly associated with increased risk of heart attack and stroke. The foam cells, in turn, release MMP’s, such as MMP-8, also known as collagenase. Collagenase’s primary function is to break-down collagen. The collagen rich protective cap, which encapsulates the atherosclerotic plaque, is now in great danger. The protective cap destroyed by collagenase results in rupture, thrombosis, followed by stroke or a myocardial infarction (heart attack). A Call to Action We can no longer afford to ignore the impact of the most common chronic inflammatory disease known to mankind; periodontitis. The consequence of relentless ongoing periodontal inflammation makes healing impossible and systemic disease more likely. The human body is continually destroying old collagen, followed by a renewal process of normal turnover. In chronic inflammatory disease, collagenases, particularly MMP-8, become excessive. The repair process is halted. Until the cessation of inflammatory response, we are at a standstill in our treatment progress, resulting in further destruction and unpredictable outcomes. What if we could slow down the breakdown of collagen or somehow inhibit the production of collagenase to an acceptable level? In research conducted at Stony Brook on incidence (%) of adverse reactions in periostat clinicals trials Headache Common Cold Flu Symptoms Tooth Ache Periodontal Abscess Tooth Disorder Nausea Sinusitis Injury Dyspepsia Sore Throat Joint Pain Diarrhea Sinus Congestion Coughing Sinus Headache Rash Back Pain Back Ache Menstrul Cramps Acid Indigestion Pain Infection Gingival Pain Bronchitis Muscle Pain periostat 20 MG bid (N=213) Placebo (N=215) 55 (26%) 47 (22%) 24 (11%) 14 (7%) 8 (4%) 13 (6%) 17 (8%) 7 (3%) 11 (5%) 13 (6%) 11 (5%) 12 (6%) 12 (6%) 11 (5%) 9 (4%) 8 (4%) 8 (4%) 7 (3%) 4 (2%) 9 (4%) 8 (4%) 8 (4%) 4 (2%) 1 (≤1%) 7 (3%) 2 (1%) 56 (26%) 46 (21%) 40 (19%) 28 (13%) 21 (10%) 19 (9%) 12 (6%) 18 (8%) 18 (8%) 5 (2%) 13 (6%) 8 (4%) 8 (4%) 11 (5%) 11 (5%) 8 (4%) 6 (3%) 8 (4%) 9 (4%) 5 (2%) 7 (3%) 5 (2%) 6 (3%) 6 (3%) 5 (2%) 6 (3%) Table 1. Periostat Product Monograph Incidence (%) of Adverse Reactions. collagen-destruction mechanisms and perio dontal disease, Golub and his colleagues made an unexpected discovery; namely, that tetracyclines, a class of drugs that had been recognized only as antibiotics, were unexpectedly found to block collagenase in mammals.6 This exciting discovery led to further research to develop a formulation of doxycycline that would inhibit collagenase (MMP-8) and other MMPs at a blood level so low that it would NOT perform as an antibiotic (Figure 2). The sub-antimicrobial level would eliminate the typical antibiotic side effects (Table 1). The drug today is known as, and prescribed under the trade name, of Periostat® (Figure 3). Over 10 million prescriptions have May 2015 www.oralhealthgroup.com 21 clinical Figure 3. been written in the U.S. alone, and it is the most widely prescribed drug for treating periodontal disease in the world. The American Dental Association (ADA) Council on Scientific Affairs published the following statement; “Periostat® has been shown to help stop the progression of periodontitis when used as directed as an adjunct to scaling and root planing, in a conscientiously applied program of oral hygiene and regular professional care.” [Note: scientifically, Periostat® is described as SDD or sub-antimicrobial-dose doxycycline.] The science found in the following doubleblind clinical studies on patients with periodontitis, and published in leading journals, is both extensive and compelling comparing SRP + SDD versus SRP + placebo; • Significantly more effective than SRP + placebo with no antibiotic side-effects.17-20 • 75 percent fewer teeth lost than patients treated with SRP + placebo. 21 • 8 0-90 percent reduction of “active” pockets21–27; “active” pockets are defined as those which get deeper with time. • No “rebound” effect.17,28 • 50-60 percent reduction of biologic mediators of tissue breakdown and bone resorption (i.e., MMP-8/collagenase, MMP-9, IL1ß).17,29 • In rapidly progressing periodontitis, adjunctive SDD (versus adjunctive placebo) produced a 73 percent reduction in “active” pockets; combined with two to three times greater mean attachment gain (i.e. 2.2 mm. vs. 0.8 mm); and significant reduction of BOP.18,24,25 Who Would Benefit from SDD? 22 With the large baby-boomer cohort aging, our dental hygiene client population is expe- riencing a rapid increase in diabetes, cardiovascular disease and other prevalent diseases, all with a common denominator; the inflammatory pathway. The success of low dose or subantimicrobial dose doxycycline (SDD), as the first-ever systemically administered collagenase inhibitor drug approved by the U.S. FDA and by Health Canada for periodontal disease, has also made a resounding impact on other inflammatory mediated diseases. As expected, this has gained significant attention from the medical community. Diabetes Consider the diabetic patient; more than one in four Canadians lives with diabetes or prediabetes. This will rise to more than one in three by 2020. 30 Chronic periodontitis is prevalent and more severe in the diabetic patient. A six-month, multicenter, randomized clinical trial was conducted on participants who had type two diabetes. All were taking stable doses of medications, HbA1c levels between seven percent and nine percent (i.e. poorly controlled hyperglycemia) and untreated chronic periodontitis. Five hundred and fourteen participants were enrolled with the treatment group (n=257) receiving SRP plus chlorhexidine oral rinse at baseline and supportive periodontal therapy at three and six months. The control group (n=257) received no treatment for six months. Enrollment was stopped early because of futility. At six months, mean HbA1c levels in the periodontal therapy group increased 0.17 percent compared with 0.11 percent in the control group, with no significant difference between groups. The study concluded that nonsurgical periodontal therapy did not improve glycemic control in patients with type two diabetes and moderate to advanced chronic periodontitis. These findings do not support the use of nonsurgical periodontal treatment in patients with diabetes for the purpose of lowering levels of HbA1c. 31 However, drastically different results were seen in a separate three-month, randomized placebo-controlled pilot clinical trial, which May 2015 www.oralhealthgroup.com clinical included 45 patients with long-standing type two diabetes and untreated chronic periodontitis. These subjects received conventional nonsurgical periodontal therapy combined with either: (a) a three-month regimen of sub-antimicrobial-dose doxycycline (SDD), or (b) a two week regimen of antibiotic therapy, or (c) placebo. Note that all subjects were taking stable doses of oral hypoglycemic medications and/or insulin. Treatment response was assessed by measuring hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), plasma glucose, and clinical periodontal disease measures. At one-month and three-month follow-ups, clinical measures of periodontitis were decreased in all groups. At threemonths, mean HbA1c levels in the SDD group were reduced from 7.2 percent units±2.2 (±SD), to 6.3 percent units±1.1, which represents a 12.5 percent improvement. In contrast, there was no significant improvement in HbA1c in the antibiotic (7.5%±2.0 to 7.8%±2.1) or placebo (8.5%±2.0 to 8.5%±2.6) groups. The results of this pilot study suggest that the treatment of periodontitis with sub-gingival debridement and three-months of daily sub-antimicrobialdose doxycycline may decrease HbA1c in patients with type two diabetes taking normally prescribed hypog lycemic agents. 32 Cardiovascular Disease The effect of subantimicrobial-dose-doxycycline (SDD) has been widely studied for its potential to reduce serum biomarkers of systemic inflammation. CRP (C-reactive protein, an acute-phase protein produced by the liver and an important biomarker in the circulation of systemic inflammation) along with several other serum biomarkers, are widely studied risk factors for coronary artery disease (CAD). These patients show elevated CRP in their blood samples, indicating patients at elevated risk for future cardiac events, such as a heart attack. One of the groups who are particularly at risk for CAD are post-menopausal women. 33,34 A randomized, double-masked, placebo-controlled clinical trial, conducted by Payne et al. and published in the JADA in March 2011, randomly assigned 128 eligible post-menopausal women with chronic periodontitis to a twicedaily regimen of subantimicrobial-dose-doxycycline (SDD), or placebo tablets, for two years as an adjunct to periodontal maintenance therapy. Following the two-year regimen, SDD significantly reduced the serum inflammatory biomarkers (CRP and MMP’s) and among women, more than five years post-menopausal, increased the HDL (high density lipoprotein) “good” cholesterol, which is correlated with reduced risk of atherosclerosis). 35 As discussed earlier, chronic inflammation, whereby macrophages secrete excessive MMPs, eventually degrade the collagen rich, fibrous protective cap. This destabilizes the atherosclerotic plaques, leading to plaque rupture, thrombosis, and heart attack (MI). It was hypothesized that if MMP activity could be inhibited or suppressed, there may be less risk of rupture of the protective cap. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study of six months of SDD, or placebo treatment, to reduce inflammation and prevent rupture events was conducted. A total of 50 patients all diagnosed with severe CAD (i.e. acute coronary syndromes or ACS) were enrolled; 24 randomized to placebo and 26 to SDD (30 patients completed the six month study; 17 SDD and 13 placebo). In the SDD-treated patients, C-reactive protein (CRP) in the circulation was reduced by 46 percent, whereas CRP was not significantly reduced in placebo patients. Interleukin (IL)-6 was decreased in SDD-treated patients but did not decrease significantly in placebo-treated patients. MMP-9 (also known as type IV collagenase) was also reduced 50 percent by SDD therapy, whereas it was unchanged by placebo treatment. [It should be recognized that these reductions in CAD biomarkers in the patient’s blood sam- May 2015 www.oralhealthgroup.com 25 clinical ples are recognized as indicators of reduced risk for cardiac events, including reduced risk for heart attack]. The study concluded that SDD appears to exert potentially beneficial effects on inflammation that could promote plaque stability, preventing plaque rupture events. 36 Osteopenia/Osteoporosis 26 The medical condition of osteoporosis, a disease characterized by low bone mass and deterioration of bone tissue, leads to increased bone fragility and risk of fracture, and in many cases, fatality. Twenty-eight percent of women and 37 percent of men who suffer a hip fracture will die within the following year. 37 A preliminary study by Payne et al. had previously demonstrated that subantimicrobial-dose-doxycycline (SDD) treatment of post-menopausal women with periodontitis and osteopenia (reduced bone mass of lesser severity than osteoporosis) reduced periodontal disease progression, including decreased alveolar bone loss, biomarkers of collagen destruction, and bone resorption locally in periodontal pockets, in a double-blind placebocontrolled clinical trial. 38 An earlier study by Golub et al. (1999), using a rat model of post-menopausal osteoporosis, clearly demonstrated that oral administration of a NON-antimicrobial doxycycline not only reduced the severity of systemic bone loss in skeletal tissue (femur), but also reduced local bone loss in the periodontium, which was associated with reduced collagenase in adjacent gingival tissues. 39 The National Institutes of Health (NIH) funded study screened 600 women of which 128 were selected. Participants had to be post-menopausal, have osteopenia, radiographic evidence of alveolar bone loss and not be taking bisphosphonates or other medications that would impact osteoporosis. The 128 post-menopausal women with chronic periodontitis and osteopenia randomly received SDD or placebo tablets daily for two years, adjunctive to periodontal maintenance therapy every three to four months. Blood was collected at baseline and at one and twoyear appointments, and sera were analyzed for bone resorption and bone formation/ turnover biomarkers. In conclusion, the twoyear regimen of SDD therapy not only reduced the clinical, radiologic and biochemical markers of periodontal disease in post-menopausal women, but also reduced the risk of conversion of mild systemic bone loss (osteopenia) into a severe form of bone disease (osteoporosis).40 Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) Historically rheumatoid arthritis and periodontitis have been linked. Is it the lack of manual dexterity and ineffective biofilm removal that was the accepted explanation several decades ago? We now understand that the link exists through vascular transport into the circulation. The inflammatory mediators (cytokines, prostaglandin, MMPs) present with oral inflammation, flow into the blood bi-directionally from the gingiva into the circulation, resulting in systemic inflammation. The profiling of elevated inflammatory markers is similar for both periodontitis and rheumatoid arthritis. A clinical study was conducted to compare the efficacy of doxycycline plus methotrexate (MTX) versus MTX alone in the treatment of early seropositive rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and to attempt to differentiate the antibacterial and anti-metalloproteinase (SDD) effects of doxycycline. Sixty-six patients with seropositive RA of <one year’s duration who had not been previously treated with disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs, were randomized to receive 100 mg of doxycycline twice daily with MTX (high, antibiotic-dose doxycycline group), 20 mg (low, NON-antibiotic-dose, i.e. SDD) doxycycline twice daily with MTX (SDD), or placebo with MTX (placebo group), in a two-year double-blind study. The study concluded that in patients with early seropositive RA, initial therapy with MTX plus doxycycline was superior to treatment with MTX plus placebo. The therapeutic responses to low-dose May 2015 www.oralhealthgroup.com clinical and high-dose doxycycline were essentially the same, except that the high-dose doxycycline group exhibited greater side effects, while SDD was similar to the placebo group. This study demonstrated that the SDD effects on host response were responsible for the beneficial effects on RA, rather than the antibacterial effect of the high-dose doxycycline.41 Conclusion The overwhelming amount of science speaks for itself. Robert Burton, an english scholar at Oxford University in the 17th century, made the following profound statement regarding health: “Restore a man to his health, his purse lies open to thee.” There is no greater wealth or richness in life than good health. Our CDHA professional statement represents our professional mandate very clearly. “I am a dental hygienist. I educate and empower Canadians to embrace their oral health for better overall health and well-being.” It’s time to put our words into action and recognize our role in reducing inflammation, and sustaining overall health for our dental hygiene clients. n Acknowledgements: The first author would like to acknowledge Dr. Lorne Golub, Dr. Ying Gu, and Dr. Maria Ryan for their assistance in preparing this manuscript. Disclaimer: The authors received no compensation for the writing of this article. References: All sites accessed March 2015. 1. Brookfield S. Developing Critical Thinkers: Challenging Adults to Explore Alternative Ways of Thinking and Acting. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass: 1987. 2.http://www.who.int/topics/infectious_diseases/en/ 3. C DC: Periodontal Disease http://www.cdc. gov/oralhealth/periodontal_disease/ 4. CDC survey finds ‘high burden’ of disease among adults August 30, 2012 http://www.ada. org/en/publications/ada-news/2012-archive/ august/prevalence-of-periodontitis 5.Cunha-Cruz J, Hujoel PP, Maupome G, Saver B. Systemic Antibiotics and Tooth Loss in Periodontal Disease. J Dent Res. 2008 Sep; 87(9): 871-876. 6.Golub LM, Lee HM, Ryan ME et al. Tetracyclines inhibit connective tissue breakdown by multiple non-antimicrobial mechanisms. Adv Dent Res 1998;12:12-26. 7.Van Dyke, TE. Periodontitis is characterized by an immune-inflammatory host-mediated destruction of bone and connective tissues that support the teeth. J Periodontol. April 2014. 8.www.perio.org/consumer/other-diseases 9.http://www.inflammationresearchfoundation. org/inflammation-science/inflammation-details/time-cellular-inflammation-article/ 10.Willerson JT, Ridker PM. Inflammation as a Cardiovascular Risk Factor. Circ Journ 2004; 109: II-2-II-10. 11. Roifman I, Beck PL, Anderson TJ et al. Chronic inflammatory diseases and cardiovascular risk: a systematic review. Can J Cardiol. 2011 Mar-Apr;27(2):174-82. 12.Wilson, PW. Evidence of systemic inflammation and estimation of coronary artery disease risk: a population perspective. Am J Med. 2008 Oct;121(10 Suppl 1):S15-20. 13.C raig RG, Yip JK, So MK, et al. Relationship of destructive periodontal disease to the acute-phase response. J Periodontol. 2003; 74(7): 1007–1016. 14.Friedewald VE, Kornman KS, Beck JD, et al. The American Journal of Cardiology and Journal of Periodontology Editors’ Consensus: periodontitis and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Am J Cardiol. 2009;104(1): 59-68. 15.Shacter E, Weitzman A. Chronic Inflammation and Cancer. Colorectal Cancer, Oncol Journ. January 31, 2002. 16.Rakoff-Nahoum S. Why Cancer and Inflammation? Yale J Biol Med. 2006 Dec; 79(3-4): 123–130. 17. C aton J, Ryan ME. Clinical studies on the management of periodontal diseases utilizing subantimicrobial dose doxycycline (SDD). Pharmacol Res. 2011 Feb;63(2):114-20. 18.A shley RA. Clinical trials of a matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor in human periodontal disease. SDD Clinical Research Team. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999 Jun 30;878:335-46. 19.Preshaw PM. Host response modulation in periodontics. Periodontol 2000. 2008;48:92-110. 20.Gu Y, Walker C, Ryan ME, Payne JB, Golub LM. Non-antibacterial tetracycline formulations: clinical applications in dentistry and May 2015 www.oralhealthgroup.com 29 clinical 30 medicine. J Oral Microbiol. 2012;4: doi: 10.3402/jom.v4i0.19227. 21. C aton JG, Ciancio SG, Blieden TM, et al. Treatment with subantimicrobial dose doxycycline improves the efficacy of scaling and root planing in patients with adult periodontitis. J Periodontol 2000:71:521-32. 22.L ee JY, Lee YM, Shin SY, Seol YJ, Ku Y, Rhyu IC, Chung CP, Han SB. Effect of subantimicrobial dose doxycycline as an effective adjunct to scaling and root planing. J Periodontol. 2004 Nov;75(11):1500-8. 23.P reshaw PM, Hefti AF, Bradshaw MH. Adjunctive subantimicrobial dose doxycycline in smokers and non-smokers with chronic periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 2005 Jun;32(6): 610-6. 24.Novak MJ, Johns LP, Miller RC, et al. Adjunctive benefits of subantimicrobial dose doxycycline in the management of severe, generalized, chronic periodontitis. J Periodontol 2002:72:762-9. 25.Mohammad AR, Preshaw PM, Bradshaw MH, Hefti AF, Powala CV, Romanowicz M.Adjunctive subantimicrobial dose doxycycline in the management of institutionalised geriatric patients with chronic periodontitis. Gerontology. 2005 Mar;22(1):37-43. 26. Novak MJ, Dawson DR 3rd, Magnusson I, Karpinia K, Polson A, Polson A, Ryan ME, Ciancio S, Drisko CH, Kinane D, Powala C, Bradshaw M. Combining host modulation and topical antimicrobial therapy in the management of moderate to severe periodontitis: a randomized multicenter trial. J Periodontol. 2008 Jan;79(1):33-41. 27.P reshaw PM, Hefti AF, Novak MJ, Michalowicz BS, Pihlstrom BL, Schoor R, Trummel CL, Dean J, Van Dyke TE, Walker CB, Bradshaw MH. Subantimicrobial dose doxycycline enhances the efficacy of scaling and root planing in chronic periodontitis: a multicenter trial. J Periodontol. 2004 Aug;75(8):1068-76. 28.C aton JG, Ciancio SG, Blieden TM, Bradshaw M, Crout RJ, Hefti AF, Massaro JM, Polson AM, Thomas J, Walker C. Subantimicrobial dose doxycycline as an adjunct to scaling and root planing: post-treatment effects. J Clin Periodontol. 2001 Aug;28(8):782-9. 29.Golub LM, Lee HM, Stoner JA, et al. Subantimicrobial dose doxycycline modulates gingival crevicular fluid biomarkers of periodontitis in postmenopausal osteopenic women. J Periodontol 2008:79:1409-18. 30.Diabetes: Canada at the Tipping Point. Canadian Diabetes Association. http://www.diabetes.ca/CDA/media/documents/publicationsand-newsletters/advocacy-reports/canada-atthe-tipping-point-english.pdf 31. Engebretson SP, Hyman LG, Michalowicz BS, Schoenfeld ER, Gelato MC, Hou W, Seaquist ER, Reddy MS, Lewis CE, Oates TW, Tripathy D, Katancik JA, Orlander PR, Paquette DW, Hanson NQ, Tsai MY. The effect of nonsurgical periodontal therapy on hemoglobin A1c levels in persons with type 2 diabetes and chronic periodontitis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013 Dec 18; 310(23): 2523-32. 32. Engebretson SP, Hey-Hadavi J. Sub-antimicrobial doxycycline for periodontitis reduces hemoglobin A1c in subjects with type 2 diabetes: a pilot study. Pharmacol Res. 2011 Dec; 64(6): 624-9. 33.R idker PM, Hennekens CH, Buring JE, et al. C-reactive protein and other markers of inflammation in the prediction of cardiovascular disease in women. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(12): 836–843. 34.R idker PM, Rifai N, Rose L, et al. Comparison of C-reactive protein and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels in the prediction of first cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(20):1557–1565. 35.Payne JB, Golub LM, Stoner JA, Lee HM, Reinhardt RA, Sorsa T, Slepian MJ. The effect of subantimicrobial-dose-doxycycline periodontal therapy on serum biomarkers of systemic inflammation: a randomized, double-masked, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Am Dent Assoc. 2011 Mar;142(3):262-73. 36.Brown DL, Desai KK, Vakili BA, Nouneh C, Lee HM, Golub LM. Clinical and biochemical results of the metalloproteinase inhibition with subantimicrobial doses of doxycycline to prevent acute coronary syndromes (MIDAS) pilot trial. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004 Apr;24(4):733-8. 37.http://www.osteoporosis.ca/osteoporosis-andyou/osteoporosis-facts-and-statistics/ 38.Payne JB, Golub LM. Using tetracyclines to treat osteoporotic/osteopenic bone loss: From the basic science laboratory to the clinic. Pharmacological Res. 63 (2), pp 121-129, 2011. 39.Golub L.M., Ramamurthy N.S., Llavaneras A., Ryan M.E., Lee H.M., Liu Y., Bain S. and Sorsa T.: A chemically modified nonantimicrobial tetracycline (CMT-8) inhibits gingival matrix metalloproteinases, periodontal breakdown, and extra-oral bone loss in ovariectomized rats. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci., 878: 290-310, 1999. 40.Golub LM, Lee HM, Stoner JA, Reinhardt RA, Sorsa T, Goren AD, Payne JB. Doxycycline effects on serum bone biomarkers in post-menopausal women. J Dent Res. 2010 Jun;89(6):644-9. 41.O’Dell JR, Elliot JR, Mallek JA, Mikuls TR, Weaver CA, Glickstein S, et al. Treatment of early seropositive rheumatoid arthritis: doxycycline plus methotrexate alone. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:621-7. May 2015 www.oralhealthgroup.com