* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Kwartaalbericht

Pharmaceutical industry wikipedia , lookup

Drug interaction wikipedia , lookup

Prescription costs wikipedia , lookup

Electronic prescribing wikipedia , lookup

Psychopharmacology wikipedia , lookup

Discovery and development of neuraminidase inhibitors wikipedia , lookup

Pharmacokinetics wikipedia , lookup

5-HT3 antagonist wikipedia , lookup

Cannabinoid receptor antagonist wikipedia , lookup

Influenza vaccine wikipedia , lookup

Adherence (medicine) wikipedia , lookup

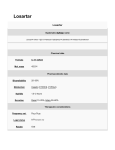

Discovery and development of angiotensin receptor blockers wikipedia , lookup

Pharmacogenomics wikipedia , lookup

Theralizumab wikipedia , lookup

NK1 receptor antagonist wikipedia , lookup

Neuropsychopharmacology wikipedia , lookup