* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Following two days of intensive battle in the hills and ridges south of

Union (American Civil War) wikipedia , lookup

Battle of White Oak Road wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Wilson's Creek wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Roanoke Island wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Island Number Ten wikipedia , lookup

Georgia in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Cavalry in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Cumberland Church wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Appomattox Station wikipedia , lookup

Battle of New Bern wikipedia , lookup

Second Battle of Corinth wikipedia , lookup

Military history of African Americans in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Mississippi in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Conclusion of the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Sailor's Creek wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Stones River wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Perryville wikipedia , lookup

First Battle of Bull Run wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Lewis's Farm wikipedia , lookup

Eastern Theater of the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Chancellorsville wikipedia , lookup

Siege of Petersburg wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Malvern Hill wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Harpers Ferry wikipedia , lookup

Second Battle of Bull Run wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Fredericksburg wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Cedar Creek wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Antietam wikipedia , lookup

Northern Virginia Campaign wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Namozine Church wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Seven Pines wikipedia , lookup

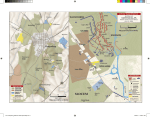

Why GEN Lee Ordered F ollowing two days of intensive battle in the hills and ridges south of Gettysburg, Pa., GEN Robert E. Lee hurled his Army of Northern Virginia against the Union center an- chored on Cemetery Ridge on the sweltering afternoon of July 3, 1863. Operationally brilliant but tactically flawed, the Gettysburg campaign constituted GEN Lee’s all-out effort to destroy the Union Army of the Potomac on Northern soil. Lee’s strategic goal was to so demoralize the Northern supporters of the war that public opinion would pressure President Abraham Lincoln’s administration to recognize the Confederate States of America and terminate the Civil War. 38 ARMY ■ July 2013 Pickett’s Charge By COL Cole C. Kingseed U.S. Army retired Dennis Steele Library of Congress Library of Congress The Gettysburg Battlefield today, from the tree line to the fence line, where Confederate soldiers, led by GEN Robert E. Lee, left, and MG George E. Pickett, below, continued their attack on Cemetery Ridge under withering Union fire. July 2013 ■ ARMY 39 Dennis Steele Dennis Steele Above, the First Pennsylvania Cavalry Memorial is situated on the flank of the Union line’s position on Cemetery Ridge. Bottom right, a statue of GEN Robert E. Lee tops the Virginia Memorial along Gettysburg National Military Park’s Confederate Avenue, which follows the position of Confederate lines that faced Cemetery Ridge on July 3, 1863. More popularly known as Pickett’s Charge, the Confederate assault of July 3 is often portrayed by modern historians as a monumental effort of military futility, but to GEN Lee, the Confederate attack was neither ill-conceived nor doomed to failure. Why did Lee order Pickett’s Charge, and what did he do to enhance the chances of its success? COL Cole C. Kingseed, USA Ret., Ph.D., a former professor of history at the U.S. Military Academy, is a writer and consultant. 40 ARMY ■ July 2013 Dennis Steele Lee’s Strategic Reassessment The Battle of Gettysburg began on July 1 as a meeting engagement when Confederate infantry from LTG Ambrose P. Hill’s corps encountered Union cavalry under command of BG John Buford on the ridges northwest of Gettysburg. Hoping to capitalize on his ability to bring more reinforcements to the field before MG George G. Meade could react in sufficient strength, GEN Lee accepted battle even though, in his words, he was “marching blind” Dennis Steele Above left, an artillery piece is displayed on the Gettysburg Battlefield. Right, Union, state and regimental memorials dot Cemetery Ridge. due to the absence of MG J.E.B. Stuart’s cavalry. GEN Lee’s gamble on July 1 paid off as converging Confederate columns smashed two Union corps by late afternoon and the Union Army retreated to Cemetery Hill south of Gettysburg. The following day, July 2, GEN Lee planned to strike both flanks of the Army of the Potomac simultaneously, but he failed to coordinate the attacks. After some of the most ferocious fighting of the war, MG Meade maintained the high ground from Culp’s Hill through Cemetery Ridge to Little Round Top by day’s end, and the Army of the Potomac survived to fight another day. The dilemma confronting GEN Lee on the evening of July 2 was knowing whether he had devised a good strategy that had been poorly executed or whether the strategy itself was flawed. As he surveyed the field, GEN Lee believed that, had LTG James Longstreet’s assault against MG Meade’s southern flank been coordinated with fellow corps commander LTG Richard S. Ewell’s attack against the northern extremity of the Union line on Culp’s Hill, the Confederates would have crushed the Army of the Potomac in a vise. In spite of the lack of coordination—for which he must bear full responsibility—GEN Lee had almost achieved success because the Army of Northern Virginia’s subordinate commanders at the brigade and division level were so skilled and the infantry was so proficient. GEN Lee’s army had nearly penetrated the Union line on Cemetery Ridge in two places before Union artillery and reinforcements took advantage of interior lines and repelled the Confederate forces. GEN Lee reasoned that if he could coordinate the attack the following day, he could still drive the Army of the Potomac from the field. Moreover, for the first time during the battle, GEN Lee had his entire army on the field before the end of July 2. MG Stuart returned with his depleted horsemen by early evening, and, most importantly, by late afternoon, MG George E. Pickett’s fresh division of 4,500 Vir- ginians arrived on the battlefield and was available for action on July 3. Lee’s Alternative For 150 years, historians have dissected GEN Lee’s rationale for remaining at Gettysburg a third day, when by his own admission he was far less optimistic for the army’s chances for success than the preceding day. Yet GEN Lee stayed to fight when he didn’t have to, even though LTG Longstreet had presented a legitimate alternative to a frontal assault against the Federal center. The only conceivable reason for Lee overriding Longstreet’s recommendation to leave Gettysburg and fight a defensive battle closer to Washington, D.C., is that Lee believed he could win at Gettysburg. He believed it from the time the Army of Northern Virginia entered Pennsylvania until midafternoon on July 3, when the remnants of LTG Longstreet’s grand assault stumbled back to their line on Seminary Ridge. In GEN Lee’s mind, the decision was never whether he would stay or not stay, whether he would attack or retreat. He had made those decisions when he accepted battle on July 1. Only by offensive action could GEN Lee achieve his intent of destroying the Union Army, and he would not retreat while any chance of success remained. Knowing that the South would never have sufficient resources to mount a subsequent invasion of the North and that time was working against the Confederacy, GEN Lee opted to attack again. He played to win, not to avoid defeat. To achieve total victory, he was willing to risk complete defeat. Coordinated Attack or Act of Desperation? Was Pickett’s Charge a coordinated attack or Lee’s last desperate gamble to win a victory over the Army of the Potomac? Twenty-twenty hindsight provides an interesting answer, but Lee suffered no illusions as to the risks accomJuly 2013 ■ ARMY 41 panying his decision to conduct a frontal assault across nearly a mile of open terrain. Eighty-one years later, Dwight D. Eisenhower made a similar decision to launch a direct assault against entrenched enemy positions above Omaha Beach on D-Day. In both cases, the challenges confronting the attacking forces were formidable. The comparisons between Pickett’s Charge and D-Day remain eerily similar 150 years after the Battle of Gettysburg. Creating the Conditions for Success Having made the decision to remain on the field and launch a massive assault, GEN Lee directed his efforts to creating the conditions conducive to success. He first placed LTG Longstreet in command of the general assault. Some historians opine that LTG Longstreet was a poor choice since he was so vehemently opposed to the attack, but GEN Lee believed he was the most proven corps commander and his “right arm” now that LTG Thomas J. (Stonewall) Jackson was dead. If not LTG Longstreet, which commander could better have managed the preparations in so little time? Should GEN Lee have assigned corps commanders Ewell, Hill, or Stuart to lead the attack? None of these commanders had ever proven able to match LTG Longstreet’s ability to deliver the hammer-like assault required on July 3. Next, GEN Lee directed an intense two-hour artillery preparation to soften the Union center before the infantry commenced its attack. Had the Confederate bombardment destroyed the Union artillery, the infantry could have traversed the no-man’s-land that separated the Union and Confederate lines with minimal casualties. If anything, the artillery bombardment on the early afternoon of July 3 was far more intense than the Allied aerial and naval bombardment that lasted a mere 40 minutes before the initial assaulting waves came ashore at Omaha Beach. Unfortu- nately for the attacking forces in 1863 and 1944, neither artillery preparation was effective, and it was left to the infantry to overcome the enemy’s defenses. Simultaneously, GEN Lee directed MG Stuart to circle the Northern right flank and strike MG Meade’s rear. Union cavalry under Brigadier Generals David M. Gregg and George A. Custer intercepted MG Stuart’s attack three miles short of Cemetery Ridge, where they fought an inclusive, yet strategically vital, engagement. The ensuing casualties, coupled with the fatigue of his horses, forced MG Stuart to depart the field short of his objective and return to the Confederate lines. Lastly, GEN Lee utilized all available resources in the attack—three divisions totaling about 12,000 men—and focused the assault against a short stretch of line along Cemetery Ridge. Two additional brigades of infantry were prepared to support any penetration of the Union line. Such an assault would have provided GEN Lee numerical superiority at the point of attack. Could the Confederate attack have succeeded? Lee certainly believed so. If everything had worked perfectly, Pickett’s Charge might well have broken the Union line. If the artillery preparation had destroyed or significantly degraded the Union center before the Confederate infantry advanced, or had MG Stuart struck the Union rear as the Southern infantry reached Cemetery Ridge, GEN Lee might have won the battle. According to Eisenhower, though, before the battle is joined, plans are everything, but once the battle is joined, plans go out the window. Reflection In retrospect, GEN Lee’s judgment seems flawed, but his method of command had always been to bring his army to the field, create the conditions for success and then leave the execution to his subordinate commanders. That recipe had Dennis Steele A statue of LTG James Longstreet stands in Pitzer Woods, where he anchored the left of his corps’ line. 42 ARMY ■ July 2013 Dennis Steele Left, plaques note Confederate unit battlefield actions along Confederate Avenue in Gettysburg National Military Park. Below, images of Confederate soldiers who charged Cemetery Ridge on July 3, 1863, decorate the base of the Virginia Memorial. Dennis Steele proven successful against five successive commanders of the Army of the Potomac. If Lee is to be faulted at Gettysburg, it should not be for ordering the attack on July 3 but rather for his lack of situational awareness. Meade was different from the Army of the Potomac’s previous commanders, fighting an orchestrated battle with a team that was far more aligned than in previous engagements. Of course, the soldiers of the Army of the Potomac simply fought much better than had been the case in the engagement just two months earlier at Chancellorsville. Part of Lee’s lack of situational awareness was his underestimation of the fighting ability of his adversary. In addition, even though it should have been clear that the leadership team put in place after Stonewall Jackson’s death was not functioning smoothly, Lee failed to intervene to coordinate his own team until it was too late to influence the action. On July 1, his instructions to Ewell to “take Cemetery Hill if practicable” lacked a sense of urgency required to ensure Confederate success. The following day, Lee left the timing of the main attack to Longstreet’s discretion and failed to ensure that Ewell was in position to support the assault on Cemetery Ridge and Little Round Top. In the words of GEN Lee’s principal biographer, Douglas S. Freeman, the “Army of Northern Virginia slipped back a year” with respect to its ability to coordinate and control the battle. Following the conclusion of the Gettysburg campaign, GEN Lee tendered his resignation to Confederate President Jefferson Davis on August 8, 1863. Before doing so, he permitted himself a rare bit of introspection as he summarized his personal assessment of the failure of the cam- paign. GEN Lee wrote to the president: I still think if all things would have worked together, it would have been accomplished. But with the knowledge I then had, and in the circumstances I was then placed, I do not know what better course I could have pursued. … Could I have foreseen that the attack on the last day would have failed to drive the enemy from his position, I should certainly have tried some other course. What the ultimate result would have been is not so clear to me. Therein lies the calamity that befell Southern arms during the Battle of Gettysburg. ✭ July 2013 ■ ARMY 43