* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Adaptation models of mountain glacier tourism to climate change: a

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

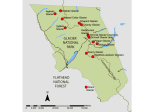

http://www.scar.ac.cn Sciences in Cold and Arid Regions 2012, 4(5): 0401–0407 DOI: 10.3724/SP.J.1226.2012.00401 Adaptation models of mountain glacier tourism to climate change: a case study of Mt. Yulong Snow scenic area ShiJin Wang 1*, ShiTai Jiao 2 1. State Key Laboratory of Cryospheric Sciences, Cold and Arid Regions Environmental and Engineering Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Lanzhou, Gansu 730000, China 2. Department of Economics and Tourism Management, Baise University, Baise, Guangxi 533000, China *Correspondence to: Dr. ShiJin Wang, Post doctor of Cold and Arid Regions Environmental and Engineering Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Sciences. No. 320, West Donggang Road, Lanzhou, Gansu 730000, China. Tel: +86-931-4967339; FAX: +86-931-4967339; Email: [email protected] Received: February 12, 2012 Accepted: July 3, 2012 ABSTRACT Mountain glaciers have an obvious location advantage and tourist market condition over polar and high latitude glaciers. Due to the enormous economic benefit and heritage value, some mountain glaciers will always receive higher attention from commercial media, government departments and mountain tourists in China and abroad. At present, more than 100 glaciers have been developed successfully as famous tourist destinations all over the world. However, global climate change seriously affects mountain glaciers and its surrounding environment. According to the current accelerated retreat trend, natural and cultural landscapes of some glaciers will be weakened, even disappear in the future. Climate change will also inevitably affect mountain ecosystems, and tourism routes under ice and glacier experience activities in these ecosystems. Simultaneously, the disappearance of mountain glaciers will also lead to a clear reduction of tourism and local economic benefits. Based on these reasons, this paper took Mt. Yulong Snow scenic area as an example and analyzed the retreat trend of a typical glacier. We then put forward some scientific and rational response mechanisms and adaptation models based on climate change in order to help future sustainable development of mountain glacier tourism. Keywords: climate change; mountain glacier tourism; adaptation models 1. Introduction Glacier tourism, as natural or mountain tourism, is an activity or event whereby glaciers and ancient glacier relics serve as main attractions, such as glacier sightseeing by cable car, aircraft and snowmobile, glacier photographing, skiing, hiking, ice climbing, and exploration and surveying teams for scientific research and environmental education (Wang et al., 2010). Glacier tourism originated from the early pilgrimage, mountaineering and expedition tourism activities in Switzerland and Norway in the early 1800s (Zumbühl and Iken, 1981), developed as mass tourism in the 1900s, subsequently became universally popular in glacier experience tourism. At present, there is extensive literature on glacier geology and geography (Ormiston and Manning, 1998; Vaske et al., 2000), but relatively little involving glacier tourism and only limited to mountain tourism and UNESCO sites (Alison and Peter, 1994; Agenda, 1999; Sanjay, 2000; Ben et al., 2008). However, today’s glacier tourism is a thriving business, and has been consciously developed and run worldwide. Historically, mountain glacier areas attracted only pilgrims, ascetics, and naturalists due to the inconvenience of traffic conditions and the restriction of tourist markets. In recent years, mountaineers, trekkers and cultural tourists have been keen to visit mountain glaciers all over the world. Additionally, climate change will also lead to a gradual shift of tourist destinations towards higher latitudes and altitudes. Present day glacier tourism, as an excellent business attraction, has been successfully developed and operated, and 402 ShiJin Wang et al., 2012 / Sciences in Cold and Arid Regions, 4(5): 0401–0407 provides valuable business and economic benefits worldwide. At present, there are more than 100 well-known mountain glacier resorts in the world as natural attractions, some of which have been listed as part of World Heritage Sites and World Biosphere Reserves because of unique and spectacular glacial landscapes and the educational significance about sensitivity to climate change (Wang and Zhao, 2011) (Table 1). Other famous scenic areas as the main attraction of glaciers include Fjords National Park in Alaska, USA; Bernardo O’Higgins National Park, Torres del Paine National Park and Laguna San Rafael National Park, Chile; Jostedalsbreen in Sogn og Fjordane, Norway, Hohe Tauern National Park, Austria; Écrins and Vanoise National Parks in the French Alps; Laponian Area in Laponia, Sweden; Vatnajökull National Park, Iceland; Gran Paradiso National Park, Italy; Langtang National Park, Nepal; Mount Kilimanjaro National Park, Tanzania, Rwenzori Mountains National Park, Ugandan; Sourceland of Three Great Rivers, Tuomuer, Bogda Peak, West Tianshan, Qilian Mountains, Gonggashan, Everest National Nature Reserves and Mt. Yulong Snow Glacier Geological Park, China. Table 1 Worldwide, well-known World Heritage glaciers Regional name Los Glaciares National Park Huascarán National Park Jostedal Glacier National Park Ilulissat Icefjord Vatnajökull National Park Jungfrau-Aletsch-Bietschhorn Albula/Bernina cultural landscape Dolomites Pyrenees-Mont Perdu Location Santa Cruz, Argentina Ancash, Peru Sogn og Fjordane, Norway Western, Greenland South-east, Iceland Valais, Switzerland Graubuenden, Switzerland Belluno, Italy Aragon Region, Spain Glacier Park 1 USA, Canada Waterton Glacier International Peace Park Olympic National Park Canadian Rocky Mountain National Parks 2 Te Wahipounamu Nanda Devi National Park Sagarmatha National Park Central Karakoram National Park Year 1981 1985 2005 2004 2004 2001 2008 2009 1997 1979, 1994, 1997 Glacier name Perito Moreno and Upsala glaciers Pastoruri Glacier Jostedal Glacier Sermeq Kujalleq Glacier Vatnajökull glacier Aletsch and Fiescher glaciers Morteratsch Glacier Marmolada Glacier Monte Perdido Glacier Malaspina and Grand Pacific glaciers USA, Canada 1995 Grinnell Glacier Washington, USA 1981 Hubert Glacier Alberta, Canada 1984 Athabasca Glacier South Island, New Zealand Uttarakhand, India Khumbu region, Nepal Gilgit-Baltistan, Pakistan Pamir National Park Gorno-Badakhshan, Tajikistan Kenya National Park Three parallel rivers of Yunnan Nanyoki, Kenya Yunnan, China 1990 1988 1979 1982 Nominated in 2008 1997 2003 Fox and Franz Josef glaciers Pindari Glacier Khumbu and Ngozumba glaciers Baltoro Glacier Fedchenko Glacier Lewis Glacier Mingyong Glacier Note: 1. Glacier Park consists of Kluane, Wrangell-St Elias, Glacier Bay and Tatshenshini-Alsek National Parks; 2. Canadian Rocky Mountain Parks include Jasper, Banff, Kootenay, Yoho, as well as the Mount Robson National Park. However, global warming has steadily increased since 1910, where global annual mean temperature has increased by 0.74 °C from 1906 to 2005, and will likely increase by 1.1–6.4 °C in 2100. Global warming during the last decades has been a "hot" phenomenon and glaciers have been melting in recent years (IPCC, 2007). Though the reaction of a glacier to climatic change involves a complex chain of processes (Nye, 1960; Meier, 1984), air temperature plays a predominant role. "The warming of the climate system is unequivocal", the overall worldwide shrinking and thinning of glaciers and ice caps since the end of The Little Ice Age in 1850 is well correlated with an increase in global mean air temperature of about 0.75 °C since the mid-19th century (Dyurgerov, 2005). Under present climate change scenarios, the ongoing trend of global and rapid, if not accelerating, glacier shrinkage on a century time scale is of non-periodic nature and may lead to the deglaciation of large parts of many alpine ranges in the coming decades (Zemp et al., 2006; Nesje et al., 2008). The retreat of mountain glaciers is more obvious and serious, where material loss is significantly higher than high-latitude and polar glaciers (Kaser et al., 2004). The current accelerated melting and retreat of mountain glaciers will not only led to an unprecedented decline and loss of mountain aesthetic climbing routes and the environment (Mueller and Vincent, 2003; Cruikshank, 2005; Vergara et al., 2007; Lewis et al., 2009), but will also cause a ShiJin Wang et al., 2012 / Sciences in Cold and Arid Regions, 4(5): 0401–0407 reduction of economic benefits in many tourist destinations with glacial features (Elsasser and Bürki, 2002; Richardson and Loomis, 2003; Scott et al., 2007). This is undoubtedly a heavy economic impact on mountain regions which relies on glacier and snow tourism as the main source of income. At present, how to rationally develop mountain glacier resources, coordinate glacier protection and tourism development, and ensure the sustainable development of mountain tourism have become a major environmental and socio-economic issue considered by tourism developers, researchers, managers, tourists, local government, NGOs and local residents. Based on these reasons, this article takes Mt. Yulong Snow scenic area as a test case to analyze its response to local climate change, and try to put forward some adaptive models to promote sustainable development of mountain glaciers. 2. Study area Mt. Yulong Snow scenic area (27°10′–27°40′N, 100°9′–100°20′E), with a highest peak "satseto" of 5,596 m a.s.l., is located in the southeastern edge of the Tibetan Plateau, and is the southernmost glacierized area of mainland Eurasia, with 15 typical monsoonal temperate-glaciers (Pang 403 et al., 2007). Mt. Yulong Snow scenic area consists of Glacier Park, Ganhaizi, Yunshanping, Maoniuping, Ganheba, Baishui River, and Sancha River attractions (Figure 1). In Galcier Park, Baishui Glacier No. 1 (BSG1) is the largest glacier in the scenic area, with an area of 1.52 km2, and length of 2.7 km (Pu, 1994), and is known as the "natural glacier museum" where most attributes of the world’s mountain glaciers of mid and low latitudes are concentrated. Due to breathtaking landscapes of glacier and subtropical mountain spectacles (e.g., high mountains, deep valleys, meadows, shrubs, forest, and glaciers), BSG1 and surrounding areas was classified as a National Glacier Geological Park by the Ministry of Land and Resources in 2009. The scenic area has a 2.9 km tourism cableway leading to Glacier Park. Owing to convenient traffic conditions and excellent service facilities, tourists can easily enjoy and experience close-up scenery of glacier landscapes without disturbing the fragile ecological environment. According to the survey of Mt. Yulong Snow scenic area, 80% of tourists are able to enjoy and view glacier and snow landscapes in Glacier Park. The number of tourist arriving in Mt. Yulong Snow scenic area has risen from 0.64 million in 1995 to 1.90 million in 2008, increasing by 196.88%. Today, tourism numbers have greatly exceeded their host populations in one year. Figure 1 Location of Mt. Yulong Snow and scenic spots 3. Impact of climate change to glacier landscapes In the context of global warming, regional warming is very significant. Annual mean air temperature, as calculated from data supplied by the Lijiang Meteorological Station at the foot of Mt. Yulong Snow, varies from 11.9 °C to 14.2 °C for the past 38 years (1972–2009). A linear trend shows that the annual mean air temperature increased significantly by 0.23 °C/decade for the period of 1972–2009, statistically significant at 0.01 level (Figure 2). Regional warming trend is obviously lower than 0.25–0.50 °C/decade of national level in the past 25 years (Zuo et al., 2004), while higher than ShiJin Wang et al., 2012 / Sciences in Cold and Arid Regions, 4(5): 0401–0407 404 0.173 °C/decade for the Sichuan Province and 0.15 °C/decade in Hengduanshan for the period of 1960–2009 (Wang, 2012). Recent climate change has caused ubiquitous reduction of glacier area on Mt. Yulong Snow. In 1957, all 19 glacier (with an area of 11.61 km2) termini observed on Mt. Yulong Snow were retreating, and by 2008 four had disappeared, with a glacier area decrease of 26.78% (about 3.11 km2). Photographs in Figure 3 and measured data shows that the retreat rate of BSG1 reached to 14.62 m/yr in 1982–2008, the altitude of its front raised by 213.3 m, the annual average elevation was 7.9 m/yr in the last 28 years, and the retreat speed obviously increased in recent years (Wang et al., 2010). More importantly, the altitude of its front rose annually by 9.5 m in 1998–2008, much higher than 3.2 m in 1957–1999 (Li et al., 2009). Rapid melting of BSG1 will threaten glacier landscape form and quality, and even endanger economic development in this mountainous region. Therefore, we should provide future response mechanisms in relation to regional climate change. Figure 2 Inter-annual variation of air temperature in Lijiang City during 1972–2009 Figure 3 Front variation of Baishui Glacier No. 1 during 1982–2008 (white line as BSG1 front, black line as the reference line). The photos taken in 1982, 1997 and 2008 were respectively provided by GuoCai Zhu, XiTao Zhao and ShiJin Wang. 4. Adaptation models to climate change 4.1. Development ideas Glaciers and snow-peaks are the most monopolistic tourist resources of Mt. Yulong Snow scenic area, but are also influential and interdependent with glacier relics, canyons, forest, meadows, natural environment, biodiversity and cultural tourism resources of Lijiang Old Town (important world cultural heritage site) (Wang et al., 2008). At the same time, glacier attraction is not determined only by glacier tourism resources but often rely on the combination characteristics of glaciers and surrounding landscapes. In view of these factors, we need to change the development model from a single glacier tourism model to a group pattern model that includes glaciers, snow-capped mountains, forests, meadows, lakes, canyons and national culture landscapes. Through group-development models, glacier tourism types and contents will expand, tourism industry chains will be extend in mountainous regions, the brand value of glacier tourism products will be enhanced in order to meet a variety of tourists’ consumption demands, and mountain glacier resources will adapt to the impact of cli- mate change. Taking the aforementioned factors into account, the ideas of glacier tourism sustainable development in Mt. Yulong Snow should focus on the following points: (1) rely on existing glacier resources to enhance the quality of glacier sightseeing; (2) stimulate the rapid development of climate-weather and vegetation tourism resources through camping and leisure projects; (3) promote the use efficiency of glacier relic tourism resources through recreation, expedition science and camping items; (4) stimulate the integration development of glacier and valley tourism by trekking, adventure and experience projects around glacier resources; (5) increase the contents of glacier tourism by products climate change and popular science education on geological museum; (6) lead the rapid development of glacier and mountain culture tourism through cultural product development. 4.2. Group-development models 4.2.1 Glacier and climate-weather tourism Climate-weather tourism resources refer to meteorolog- ShiJin Wang et al., 2012 / Sciences in Cold and Arid Regions, 4(5): 0401–0407 ical landscapes, weather phenomenon and their combination with cryosphere, lithosphere, hydrosphere, and biosphere tourism resources in different regions. These resources include clouds, mists, moonlight, sunrise, snow, and glaciers, which constitute the important attractions in Mt. Yulong Snow scenic area. Snow and glacier landscapes are the most 405 important climate resources, and their shapes change with the seasons. More importantly, Mt. Yulong Snow enjoys a prominent and complete vertical mountain climate belt with an elevation gradient of warm, warm and cool, and cold temperatures from the valley to the top of the mountains (Table 2). Table 2 Climate-weather tourism resource types in glacier areas of Mt. Yulong Snow Elements Landscape Remark Wind, rain, overcast, sunshine Meteorology The evening rays of sunshine on snow-capped mountain create a rainbow of colors, producing a colorful glow on glaciers and snow. Glaciers Climate Cloud and mist Evergreen Low clouds Cloud formations Less dense mists Ice, snow, frost, dew Snow cover Sun, moon, and stars Morning scenery Evening scenery Night scenery Glaciers are a multi-year climate product. Evergreen landscapes, snow and glaciers constitute the scenic essense of green landscapes and snowy peaks in the subtropics of China. In June, ribbon-like white clouds encircle snow-capped mountains, where glaciers seem to disappear directly into the sea of clouds. Some clouds produce a variety of forms such as a dragon that float above the snowy peaks. In winter and spring, a variety of unique mists blanket the glacier. Sunlight shining down on a snow covered mountain creates flickering phenomena creating a pleasant sensation to the viewer. Early morning sunshine on snowy mountains and glacier landscapes create a variety of colors. Snow-capped mountains are spectacular during sunset. Snow-capped mountains and moonlight complement each other. In view of limited utilization of climate-weather tourism resources, Mt. Yulong Snow scenic area should focus on camping and leisure items in Maoniuping and Yunshanping in order to supplement and improve existing tourism products. At the same time, the scenic area should also implement temporary camping projects in Zhupengping and Chuncaoping near BGS1 and build simple temporary camping locations in Ganheba and Sanchahe (Figure 1). Through a combination of camping, leisure projects and glacier sightseeing, Mt. Yulong Snow scenic area can take full advantage of climate-weather tourism resources (e.g., sunrise, clouds, evening rays, snow, glacier landscapes) so as to provide increased landscape products with higher ornamental value to a variety of tourists. It should be noted that generated garbage, waste water, and solid waste from camping activities must be collected and processed, putting an end to environmental pollution. zontal outwash deposit and terminal moraine, creating open terrain conditions and beautiful natural landscapes. In addition, these landscapes spread out to other scenic areas close to tourist service centers which are relatively accessible. Based on the aforementioned factors, Mt. Yulong Snow scenic area should make full use of modern galcier landscapes in Glacier Park, ancient glacier relic landscapes in Ganheba, and other important attractions, such as forest vegetation, alpine flora, and alpine ice-worn cone karst. Thus, the scenic area can carry out proper hiking, adventure, fitness, scientific research, popular science, summer (winter) camping, and other special tourism projects. This will establish Mt. Yulong Snow as a well-known natural leisure resort with economic, environmental, low-carbon, and vacation benefits. At the same time, the scenic area should also actively develop Mt. Yulong Snow as a base for mountain glaciology, geology, ecology, tourism practice and popular science in China. 4.2.2 Glacier and ancient glacier relic tourism 4.2.3 Glacier and glacier geological museum tourism In Glacier Park, there are diverse glacier landscapes, such as hanging, cirques, valley, cirques-hanging, and cirques-valley glaciers, and a variety of glacier relic types such as "U" and "V" shaped valleys, hanging valley, edge ridge, horn, cirque, lateral moraine, terminal moraine, drumlin, roche moutonnee, glacier pavement, and boulders, concentrated in Ganheba. Ganheba belongs to the Alpine U-shaped valley, where the valley floor distributes a hori- The rapid melting of glaciers will result in the reduction of glacier tourism resources and a decrease in landscape quality. However, a glacial geology museum is an important reserve resource for sustainable glacier tourism. In fact, glacier museums have been developed and run successfully in Switzerland and Norway. It is very important and significant to set up glacier museums and a popular science educa- 406 ShiJin Wang et al., 2012 / Sciences in Cold and Arid Regions, 4(5): 0401–0407 tion base in the tourist service center by combining glacier tourism, popular science and geographical practices with glaciers, geology, forest vegetation, ecology, and environmental education functions. Glacier tourists and researchers will learn more about correlative formations and knowledge of glacier form and change mechanism, formation and characteristics of ancient glacier relics and landforms, the relationship among glaciers, climate and runoff changes, the response of glaciers to global climate change, and the role of glacier tourism for regional economic and social development. At the same time, the glacier museum and popular science education can display glacier landscapes, glacier information and protection, and also raise tourists’ awareness of ecotourism, low-carbon tourism and environment protection. This can be accomplished by use of pictures, samples of glaciers, vegetation, and rocks, three-dimensional virtual scenery, and multi-media, glacier forums, and consultation. This will provide a new paradigm or ideas for the sustainable development of glacier tourism. 4.2.4 Glacier and alpine vegetation tourism Glacier scenery, snowscape, and alpine vegetation are typical landscape combinations coexisting on Mt. Yulong Snow. Forest landscape of Yunshanping, grassland landscape of Maoniuping, and glacier landscape of Glacier Park are the main attractions of Mt. Yulong Snow scenic area, indicating potential and direction of glacier tourism group development with alpine vegetation resources. On Mt. Yulong Snow, typical high-altitude climate and excellent soil conditions provide healthy alpine vegetation and environment. For example, from 1,800 m above sea level to snow covered mountain areas at 4,500 m, Mt. Yulong Snow enjoys multiple climates ranging from subtropical, temperate to frigid zones. Evergreen broadleaf forest exists at 2,400–2,900 m; at 2,700–3,200 m there exists a mixed forest of conifers and broadleaf; coniferous trees are at 3,100–4,200 m; shrubs are located at 3,700–4,300 m; alpine plants can be found at 4,300–5,000 m; and glaciers above 5,000 m lack plant life. In the 20 primitive forests on the mountain, there are over 20 rare and endangered species of plants under state protection, such as Chinese hemlock and Yunan torreya, and 145 genera and 3,200 species of seed plants (alpine Rhododendron has more than 80 species) (Wang, 2002). However, the integrated development of alpine vegetation and glacier tourism resources needs to be developed. In view of the aforementioned factors, the scenic area should first consider adding viewing platforms and plank roads around shrubs (e.g., Rhododendrons) and woodlands near the front of glaciers, and provide trails or cableways connected to these platforms and roads. Thus, tourist will not only enjoy the sight of glacier landscapes at short range, but also alpine vegetation. In addition, tourism managers can also implement camping activities in the terminal of BSG1, where tourist can witness the coexistence phenomenon be- tween glaciers and diverse vegetation landscapes (e.g., beautiful Rhododendrons blanketing the snow mountain). Relying on alpine climate tourism resources, group-development between glacier and alpine vegetation tourism are bound to extend the content and functions of mountain glacier tourism in order to adapt to a diverse demand of tourists’ consumption. 4.2.5 Glacier and valley tourism At the east foot of Mt. Yulong Snow is a river valley, called Baishui River (Figure 1), fed by a melting glacier and snow. Glaciers, glacial runoff, and river valleys form a systematic and inseparable combination landscape and are interdependent with each other. At present, Baishui River valley has not been developed. Thus, visitors can not arrive directly at BSG1 through the valley to appreciate and experience the comprehensive landscapes of glaciers, glacial runoff and the river valley. However, the river valley from BSG1 to Sachahe (the upper reaches of Baishui River) (Figure 1) is very suitable for hiking and expedition activities in summer and autumn. Here, tourist can not only appreciate distant glacier and forest landscapes, but also experience nature, waterfalls, paddle boats and enjoy the clean fresh air. Taking into account these factors, Baishui River valley should be developed actively as a new tourism project. Certainly, the design of tourism products should highlight the comprehensive landscape features of snow-capped mountains, glaciers, river valleys, lakes, waterfalls, forest, and flora. At the same time, the design and building of valley tourism routes should promote the ideas of nature, ecology, culture and safety. Through group-development between glaciers and river valley tourism resources, scenic areas will enhance the competitiveness of mountain tourism. 4.2.6 Glacier and culture tourism Mountainous regions usually possess cultural heritages based on long-term historical process. Mt. Yulong Snow is a sacred mountain to the Naxi and other people in this area, and is also the source of Naxi culture (important part of world cultural heritage of Lijiang Old Town). At the same time, Naxi, Tibetan, Yi, Pumi and Lishu people have lived on Mt. Yulong Snow for thousands of years, and have created interesting cultures. For example, Dongba characters, the living pictographs, the Baisha Fresco that combines features of Han and Tibetan paintings and ancient Naxi music (parts of Lijiang Old Town), handed down from the Tang Dynasty, have received inspiration from the sacred mountain. On the other hand, from ancient to modern times, many scholars are attracted to the magic of Mt. Yulong Snow and express their sincere praises to it. A poet described it as "a jade dragon raising head toward the heaven above and viewing its own image in the mirroring Dianchi Lake". Another line describes Mt. Yulong Snow as piled with thousands of layers of jade and good wine unparallel in the world ShiJin Wang et al., 2012 / Sciences in Cold and Arid Regions, 4(5): 0401–0407 (Wang, 2002). The variety of cultural resources on Mt. Yulong Snow has a long history and huge tourism value, so future group-development between glacier landscapes and mountain culture tourism should involve three aspects: (1) exhibit the poems of snow and glacier culture on Mt. Yulong Snow by television and film so as to expand the scenic area’s reputation; (2) publish and issue cultural tourism products and snow and glacier landscapes (collection of poems, paintings, pictures, images, and other products), allowing tourists to understand Mt. Yulong Snow scenic area; (3) build artificial landscapes (e.g., stone walls, exhibition halls) with poems and Naxi culture at the tourist service center on Mt. Yulong Snow to exhibit their content, spatial and temporal beauty. Through group-development of glaciers, snow and mountain culture resources, tourist will intuitively understand glaciers and snow landscapes and its culture history on Mt. Yulong Snow. 5. Conclusion Adapting to the impact of climate warming on mountain glacier tourism, Mt. Yulong Snow scenic area must focus on group-development models that include glacier sightseeing, hiking, exploration, camping, sports fitness, leisure, popular science education, culture tourism and other tourism projects, thereby reducing the pressure of glacier tourism. In the context of global warming, mountain glacier tourism will face serious effects, such as glacial retreat. Therefore, mountain destinations should assess in advance the impacts from glacier retreat, enhance the quality of existing glacier sightseeing and experience projects, look for alternative tourism products, and extend the chain of glacier tourism industry in order to cope with the consequences of global climate warming to mountain glaciers tourism. At the same time, mountain destinations should implement a dominant strategy of ecotourism and low-carbon tourism, and ultimately promote glacier tourism sustainable development by clean energy and green consumption. Acknowledgments: This study was partially funded by the open fund (SKLCS 2011-04) from Stake Key Laboratory of Cryospheric Sciences and National Social Science Foundation of China (12BJY127). The author thanks fellow colleagues for their constructive comments of this manuscript. REFERENCES Agenda M, 1999. Mountains of the world: Tourism and sustainable mountain development. Institute of Geography, University of Berne, Switzerland. Alison G, Peter W, 1994. Managing growth in mountain tourism communities. Tourism Management, 3(15): 212–220. Ben O, Ellen W, Brian HL, 2008. The place of glaciers in natural and cultural landscapes. In: Darkening Peaks: Glacier Retreat, Science and Society. University of California Press, USA. Cruikshank J, 2005. Do Glaciers Listen? Local Knowledge, Colonial Encounters, and Social Imagination. University of British Columbia Press, Vancouver, pp. 30–150. Dyurgerov M, 2005. Mountain glaciers are at risk of extinction. In: Huber 407 UM, Bugmann HKM, Reasoner MA (eds.). Global Change in Mountain Regions. Springer, Netherlands. Elsasser H, Bürki R, 2002. Climate change as a threat to tourism in the Alps. Climate Research, 20: 253–257. IPCC (Intergovernment Panel on Climate Change), 2007. Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Summary for Policymakers Report of Working Group II of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. Kaser G, Georges C, Juen I, Mölg T, Wagnon P, Francou B, 2004. The behavior of modern low-latitude glaciers. Past Global Changes News, 12: 15–17. Lewis AO, Glenn T, Robert SA, Jason B, Darrell K, Gerard R, William P, Chaolu Y, 2009. Integrated research on mountain glaciers: Current status, priorities and future prospects. Geomorphology, 103: 158–159. Li ZX, He YQ, Wang SJ, Jia WX, He XZ, Zhang NN, Zhu GF, Pu T, Du JK, Xin HJ, 2009. Changes of some monsoonal temperate glaciers in Hengduan Mountains region during 1900–2007. Acta Geographica Sinica, 64(11): 1322–1323. Meier MF, 1984. The contribution of small glaciers to sea level rise. Science, 226: 1418–1421. Mueller DR, Vincent WR, 2003. Break-up of the largest Arctic ice shelf and associated loss of an epishelf lake. Geophysical Research Letters, 30(20): 1–4. Nesje A, Bakke J, Dahl SO, Lie O, Matthews JA, 2008. Norwegian mountain glaciers in the past, present and future. Global and Planetary Change, 60(1–2): 10–27. Nye JF, 1960. The response of glaciers and ice-sheets to seasonal and climatic changes. Proceedings of the Royal Society A, 256(1287): 559–584. Ormiston DG, Manning RE, 1998. Indicators and standards of quality for ski resort management. Journal of Travel Research, 36(2): 35–41. Pang HX, He YQ, Zhang NN, 2007. Accelerating glacier retreat on Yulong Mountain, Tibetan Plateau, since the late 1990s. Journal of Glaciology, 53(181): 317–319. Pu JC, 1994. Glacier Inventory of China: the Changjiang River Drainage Basin. Gansu Culture Press, Lanzhou, pp. 117–129. Richardson RB, Loomis JB, 2003. The effects of climate change on mountain tourism: a contingent behavior methodology. First International Conference on Climate Change and Tourism, Djerba, Tunisia. Sanjay K, 2000. Tourism in protected areas: The Nepalese Himalaya. Annals of Tourism Research, 3(27): 661–681. Scott D, Jones B, Konopek J, 2007. Implication of climate and environmental change for nature-based tourism in the Canadian Rocky Mountains: A case study of Waterton Lakes National Park. Tourism Management, 28: 570–572. Vaske JJ, Carothers P, Donnelly MP, 2000. Recreation conflict among skiers and snow boarders. Leisure Sciences, 22(4): 297–313. Vergara W, Deeb AM, Valencia AM, Bradley RS, Francou B, Zarzar A, Grünwaldt A, Haeussling SM, 2007. Economic impacts of rapid glacier retreat in the Andes. EOS Trans. American Geophysical Union, 88(25): 261–264. Wang SJ, He YQ, He XZ, Yuan JP, 2008. Tourism resource protection and development in a typical temperate-glacier region in China: A case study of Mt. Yulong Snow scenic region. Journal of Yunnan Normal University (Humanities and Social Sciences), 40(6): 38–43. Wang SJ, He YQ, Song XD, 2010. Impacts of climate warming on Alpine Glaciers tourism and adaptive measures. Journal of Earth Science, 21(2): 166–178. Wang SJ, Jiao ST, Xin HJ, 2012. Spatio-temporal characteristics of temperature and precipitation in Sichuan Province, Southwestern China in recent five decades. Quaternary International. DOI: 10.1016/j.quaint.2012.04.030. Wang SJ, Zhao JD, 2011. Potential evaluation and spatial development strategies of glacier tourism in China. Geographical Research, 30(8): 1528–1542. Wang Y, 2002. Travel Yulong Snow Mountain. China Travel and Tourism Press, Beijing. Zemp M, Haeberli W, Hoelzle M, Paul F, 2006. Alpine glaciers to disappear within decades? Geophysical Research Letters, 33: L13504. DOI: 10.1029/2006GL026319. Zumbühl H, Iken A, 1981. Glacier in the Bernese Alps and their exploration. Berner Illustrated Encyclopedia. Nature, 1: 54–61. Zuo HC, Lu SH, Hu YQ, 2004. Variations trend of yearly mean air temperature and precipitation in China in the last 50 years. Plateau Meteorology, 2: 238–244.