* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Tuberculosis transmission - National Tuberculosis Institute

African trypanosomiasis wikipedia , lookup

Leptospirosis wikipedia , lookup

Human cytomegalovirus wikipedia , lookup

Diagnosis of HIV/AIDS wikipedia , lookup

Neglected tropical diseases wikipedia , lookup

Marburg virus disease wikipedia , lookup

Onchocerciasis wikipedia , lookup

Epidemiology of HIV/AIDS wikipedia , lookup

Schistosomiasis wikipedia , lookup

Dirofilaria immitis wikipedia , lookup

Carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae wikipedia , lookup

Neonatal infection wikipedia , lookup

Hepatitis C wikipedia , lookup

Hepatitis B wikipedia , lookup

Middle East respiratory syndrome wikipedia , lookup

Eradication of infectious diseases wikipedia , lookup

Microbicides for sexually transmitted diseases wikipedia , lookup

Coccidioidomycosis wikipedia , lookup

Sexually transmitted infection wikipedia , lookup

Oesophagostomum wikipedia , lookup

Mycobacterium tuberculosis wikipedia , lookup

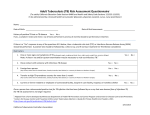

TB TRANSMISSION NTI Bulletin 2006, 42/3&4, 63 - 67 Transmission of tuberculous infection and its control in health care facilities KB Gupta1, A Atreja2 Abstract Tuberculosis (TB) is a global problem, with varied prevalence in different countries. It affects all age groups and ranks as a major cause of mortality and morbidity. Despite intensive efforts by various agencies, the scenario of control of disease transmission and its eradication still remains a distant goal. It is important to break the chain of events by controlling the transmission of tuberculosis. This will affect the incidence of disease in coming years. This disease is affecting the most economically productive strata of the society. The rising alliance between TB and Human Immuno Deficiency Virus (HIV) is a cause of concern globally as the management and outcome of both the diseases is affected. Proper planning needs to be done at various levels so that the transmission of infection can be controlled. Adopting policies that affect the transmission of TB infection along with proper disease management options can go a long way in suppressing the menace of TB and can possibly control the growing incidence of TB and HIV. Transmission control methods can also decrease the risk of spread of TB among health care workers (HCW). Introduction Tuberculosis has been declared as a global emergency in 1993. It is one of the most devastating and widespread infections in the world and is an important cause of mortality and morbidity, affecting all age groups, especially in the developing world. It ranks as one of the most common causes of adult death. There were 8.8 million new cases of tuberculosis in 2005 and approximately 1.6 million deaths all over the world in the year 2005, due to tuberculosis per se1. More than 80% of all tuberculosis cases are concentrated in subSaharan Africa and Asia. The last decade of 20th century has been a witness to the alliance between Mycobacterium tuberculosis and HIV and this has lead to the resurgence of the disease. Causes of transmission of tuberculosis The transmission of tuberculosis is predominantly airborne. An “open case” or a sputum positive case is the source of infection and the cause of transmission of tuberculous infection to other persons in the community. Tuberculosis is transmitted as airborne particles, or droplet nuclei which patients with pulmonary or laryngeal TB generate when they sneeze, cough, speak or sing. Normal air currents can keep infectious particles airborne for prolonged periods and spread them throughout a room or a building2. Recent studies have shown that those people who are in close vicinity to the infective TB cases have an increased chance of acquiring the disease3. These include: 1. Health care workers (HCW) - Doctors, Pathologists, Microbiologists, Nursing staff, Lab staff, etc. 1. Professor and Head, 2. Junior Resident, Department of tuberculosis and respiratory medicine, 18/6J Medical Enclave ,Pt. B.D. Sharma PGIMS, Rohtak-124 001 (Haryana) 63 2. Young children in the household 3. Other family members In most instances, the infection is transmitted from pulmonary smear positive cases (open cases) to other people. Children are rarely sputum positive, hence are much less likely to be source of infection for others. However case reports of children who are sputum positive have been documented. These patients were later on traced as a source of infection for other persons including children in their vicinity4. Various risk factors facilitating the transmission of tuberculous infection from a source to contacts and its subsequent manifestations include : 1. Co-infection with HIV 2. Age of the patient 3. Co-morbid conditions like diabetes mellitus 4. Occupational exposure e.g. silicosis 5. Malnutrition and cachexia 6. History of smoking 7. Industrial worker 8. Delay in diagnosis of disease. Various research studies indicate that health care setups are often at higher risk of transmission of tuberculous infection5. The risk may be higher in places where health care providers directly encounter patients with tuberculosis especially before diagnosis and treatment or in setups where high risk procedures are carried out. Such procedures include: 1. Aerolised medication and treatment 2. Bronchoscopy 3. Endotracheal intubation 4. Suctioning procedures 5. Procedures that stimulate coughing 64 Environmental factors affecting the transmission include: 1. Exposure in relatively small and enclosed spaces 2. Lack of adequate ventilation to clean the environment through dilution or removal of infectious droplet nuclei 3. Recirculation of air containing infectious droplet nuclei. Garret et al. estimated that 49% of health care workers had TB infection compared to 25% of general population6. Children as a special group are highly affected by these open cases. Although children are rarely sputum positive but they can transmit infection, as has been documented in a large school based study and past experiences of community outbreaks4,7. They are also more likely to develop disease after acquiring infection and are significantly more likely to develop extra pulmonary tuberculosis and disseminated tuberculosis i.e. tubercular meningitis and military tuberculosis. The lifetime risk of developing TB disease after infection has been reported as8. adults 5-10% adolescents 15% children < 5 yrs 24 % children < 1 yr 43 % Pediatric tuberculosis is an indicator of recent transmission of tuberculosis and an indirect indicator of the success of the tuberculosis control programme and pediatric health programme. Sub-Saharan Africa forms the depot store for tuberculosis with highest incidence of tuberculosis in all age groups. An autopsy study carried out in Zambia found that 20% of children dying of respiratory disease had evidence of tuberculosis. TB and HIV- the combination of lethality TB and HIV co-infection is a major cause of concern as the incidence of HIV is increasing. Globally an estimated 20 million people are coinfected with TB and HIV. 13% of tuberculosis cases occur in HIV infected people1. The rationale behind increased focus on TB and HIV co-infection is bi-directional. Of HIV infected individuals with pre-existing latent TB infection; about 7% develops tuberculosis each year as observed in a study carried out in Chennai i.e. a risk that is about 30 times higher than the risk for those without HIV co-infection9. The percentage of children with TB and HIV coinfection is also increasing. A study from Rio De Janeiro, Brazil showed an increase from 23 to 31% from 1995 to 199910. A study in S. Africa showed 48% of children with culture proven TB having HIV11. Recent studies show increased rates of transmission of infection with particular life styles such as prisons, bars, homeless shelters and other social gatherings. Studies done on jail inmates show disproportionately high prevalence of infection. Structural factors in most jails, such as overcrowding and poor ventilation increased the risk for tuberculosis in jail inmates. At the same time, rapid movement of inmates in and out of the jail makes it difficult for many inmates to complete any TB treatment that is started in jail12. of RNTCP is followed by all doctors, majority of infectious patients can be diagnosed as early as 3 weeks. 2. Drawing up a proper infection control plan. 3. Training of health care workers in handling tubercular cases and their specimens. 4. Maintaining quality control in diagnosis and culture techniques 5. Proper education of patient for health and hygiene (b) Inpatient management for severely sick & highly infectious patients :- 1. Establish separate wards, areas, rooms for severely sick and infective TB patients especially who require surgical intervention. 2. These wards should be placed away from wards with non-TB patients especially high risk pediatric and immune-compromised patients. 3. Wards should be well ventilated with proper sunlight. 4. Windows of opposing walls should be kept open to ensure cross ventilation. 5. Direction of air flow should always be away from infected patients. 6. Isolation policies should be strictly enforced wherever they are essentially required. 7. Use of a surgical mask/disposable mask when patient moves around in the ward. (c) Certain indoor precautions on the part of health care workers are advocated :- 1. Cough inducing procedures should be done only when absolutely necessary and should be avoided in patients with established diagnosis. 2. Avoid intubations in potentially infectious TB patients. Preventive measures Adequate preventive measures are a keystone to control the spread of pulmonary tuberculosis. These include: (a) Administrative control measures ensuring :- 1. Early diagnosis and adequate treatment of sputum smear positive pulmonary tuberculosis cases. If diagnostic algorithm 65 3. Improve ventilation in intensive care unit areas 4. Use personal respiratory protection for the procedures that are likely to produce aerosols in TB patients. 5. Proper coverage of sputum disposal bins and bags 6. TB isolation rooms should be on preferably single patient occupancy. Proper precautions should be used during aerosole generating procedures. Indiscriminate use of these procedures in suspected patients may increase the spread of infection among contacts and health care workers. These precautions include: a) proper bronchoscopy suite. b) use of N95 masks by health care workers13. c) Surgical gloves to handle specimen. d) Adequate measures to reduce bacterial load in such places e.g. HEPA13 (High efficacy particulate absorption) filters and UVGI (Ultraviolate germicidal irradiation). Other environmental control measures to reduce the transmission of tuberculosis in indoor patients in advanced hospital settings include : 1. Maximizing natural ventilation through open windows. 2. Use of negative pressure ventilation in indoor wards and isolation rooms. 3. Use of mechanical ventilation in indoor wards by the use of exhaust ventilation systems and window fans. The minimum recommended ventilation is 12 air changes /hour. 4. Air filtration to remove infectious particles 5. Use of UVGI filters to kill bacilli. 6. Use of portable HEPA filters on the floors and ceilings to reduce the bacterial load in the contaminated air in the ward. 66 7. Waiting areas, sputum collection areas, examination rooms and wards should be open to the environment and should have adequate supply of fresh air and sunlight. 8. In sputum collection rooms bare bulbs to irradiate the entire booth when not occupied. 9. Cautious handling of the sputum specimens and proper precautions while processing the specimens which are likely sources of pulmonary and cutaneous TB in working medical and lab staff. 10. Personal respiratory protection/Respirators: they are the last line of defense for health care workers against nosocomial mycobacterial infections: the personal respirator should meet the following criteria. (a) The ability to filter particles 1 micrometer in size in the unloaded state with filter efficiency of 95%. (b) Ability to obtain face seal leak of 10%. These respirators are especially indicated for procedures that are known to generate aerosols. Along with all these methods to reduce the transmission, proper patient education and training is very essential14. Health education for children should include the need to observe personal hygiene. One should cover his/her mouth while coughing15. Sputum should be collected in tissue paper and properly disposed off. Hands should be properly washed after handling of sputum. Conclusion Adopting these policies stringently can go a long way in preventing the spread of pulmonary TB infection and helping in realizing the goals set for the control and subsequent elimination of this global epidemic. References : 1. Global Tuberculosis Control – Surveillance, Planning and Financing, WHO Report 2007, Geneva, World health organization. 2. Tuberculosis: an air borne disease. UN Chron 1998; (2): 73. 3. Health-care.net: How is tuberculosis transmitted. URL: http:/respiratory – lung. health-cares. net/ Tuberculosistransmission. php. 4. 5. Cooreman E. Global epidemiology of pediatric tuberculosis. In: Kabra SK, Seth V, editors. Essentials of tuberculosis in Children. New Delhi; Jaypee Brothers. 2006; 11-21. Centre for Disease Control. Guidelines for preventing the transmission of tuberculosis in health care facilities. MMWR 1994; 43 (RR-13): 1-132. 6. TB in the workplace. http://www.map.edu/ openbook/0309073306/html/95.html, Copyright, 2000. 7. Eamramond P, Jaramillo E: Tuberculosis in children, re-assessing the need for improved diagnostic and global control strategies: Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2001, 5, 594-603. 8. Mailler F, Seal R, Taylor M: Tuberculosis in children; Boston, Little Brown, 1963. 9. Swaminathan S, Ramachandran R, Bhaokaran G, et al: Risk of development of TB in HIV infected patients; Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2000, 4, 839-844. 10. Alves R, Ledo A, Cunha A; et al : Tuberculosis and HIV coinfection in children under 16 years of age in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2003, 7, 198199. 11. Jeena P, Pillay P, Pillay t: Impact of HIV1 Co-infection on presentation and hospital related mortality in children with culture pulmonary TB in Durban, South Africa; Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2002, 6, 672-678. 12. Audney AR, Mark NL, Cheryl AR, Lauri BB, Theodore MH: Assessment of TB screening and management practice of large jail systems; Public Health Rep 2003, 118 (6), 500-507. 13. Manangan LP, Bennett CL, Tablan N, Simond DS, Pugliese G, Collazo E et al: Nosocomial tuberculosis prevention measures among 2 groups of US hospitals 1992-1996; Chest 2000, 117, 380-384. 14. Krishnadas BH: Perceptions and practice of sputum positive pulmonary TB patients regarding their disease and its management; NTI Bulletin 2005, 41/1 & 2, 11-17. 15. Guidelines for preventing the transmission of tuberculosis in Canadian Health Care facilities and Other Institution Settings. 1996; vol. 22S1 67