* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Anglo-Saxons - British Museum

Roman infantry tactics wikipedia , lookup

Structural history of the Roman military wikipedia , lookup

Travel in Classical antiquity wikipedia , lookup

Legislative assemblies of the Roman Republic wikipedia , lookup

Sino-Roman relations wikipedia , lookup

Alpine regiments of the Roman army wikipedia , lookup

Ancient Roman architecture wikipedia , lookup

Military of ancient Rome wikipedia , lookup

Roman historiography wikipedia , lookup

Food and dining in the Roman Empire wikipedia , lookup

East Roman army wikipedia , lookup

Demography of the Roman Empire wikipedia , lookup

Roman army of the late Republic wikipedia , lookup

Culture of ancient Rome wikipedia , lookup

Ancient Roman pottery wikipedia , lookup

Early Roman army wikipedia , lookup

Slovakia in the Roman era wikipedia , lookup

Education in ancient Rome wikipedia , lookup

Roman agriculture wikipedia , lookup

Wales in the Roman era wikipedia , lookup

Switzerland in the Roman era wikipedia , lookup

Roman funerary practices wikipedia , lookup

Romanization of Hispania wikipedia , lookup

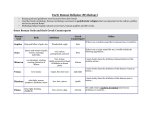

Roman Britain Key Stage 2 Resource Pack Background information for teachers Learning and Audiences Department Great Russell Street Telephone + 44 (0) 20 7323 8511 / 8854 London WC1B 3DG Facsimile + 44 (0) 20 7323 8855 Switchboard + 44 (0) 20 7323 8000 [email protected] www.thebritishmuseum.ac.uk British Iron Age Around 750 BC iron working techniques reached Britain from Europe. Whilst bronze was still used for objects such as jewellery; iron was used for tools. In England and Wales, the Iron Age ended when the Romans arrived in AD 43, although in Scotland and Ireland, Iron Age ways of life continued after this date. Iron Age Britain was essentially rural with most people living in small villages. Iron axes and iron tipped ploughs make farming more efficient and output increased. Wheat, barley, beans and brassicas were grown in small fields. Timber was used for fuel and for building houses, carts, furniture and tools. Cattle provided milk and leather and were used to pull the plough while sheep provided milk, meat and wool. Chickens were introduced at the end of the Iron Age. Another form of constructed community space was the hillfort which began to be built around 1500 BC. Use peaked during the late Iron Age and they may have been defensive or used for social and trading gatherings. Communities had contacts with each other and Western Europe. Through these contacts La Tène art styles spread (from 900 to 500 BC) until it was used across most of the British Isles. Trade, internal and with continental Europe, flourished based on Britain's mineral resources. About 100 BC, iron bars began to be used as currency and from around 150 BC coins developed. British Iron Age people did not build temples or shrines to worship their gods and there are very few statues of these gods. Instead, gods were seen as being everywhere and religious offerings were made in the home, around farms and in the countryside. By AD 1, south-eastern England was controlled by powerful rulers who had close contacts with the Roman Empire. Rulers such as Tincommius (Tincomarus), Tasciovanus and Cunobelinus are known from their coins and controlled areas of land from centres such as St Albans, Colchester, Chichester and Silchester. Roman Britain The Roman general Julius Caesar made two expeditions to Britain in 55 and 54 BC following his conquest of Gaul. During these expeditions, the Romans invited the British people to pay tribute in return for peace, established client rulers and brought Britain into Rome's sphere of influence In AD 43, a Roman invasion force landed in Britain and quickly took control of the south-east before heading north and west. Then in AD 61, while the Roman army was in Wales, Boudica, ruler of the Iceni people, provoked by Roman seizure of land and the brutal treatment of her family rebelled against Roman rule. The Iceni, joined by the Trinovantes, destroyed the Roman colonies at Camulodunum, Colchester, Verulamium (St Albans) and London before the Roman army finally defeated the rebels in the Battle of Watling Street. In Britain, towns often began as military camps or planned settlements for former soldiers. At the centre of the town was a paved space (the forum) often used as a market place. Facing onto the forum were official buildings such as the temple and the basilica (used for local government, tax-collecting and recordkeeping). There were also public buildings such as a bath house, theatre and amphitheatre for gladiatorial combats. In Britain the largest towns were London and Colchester. The Romans built rectangular houses, with brick walls and tiled roofs, known as villas. Some people continued to live in round houses, especially in areas where Roman ways of living had less influence. Villas usually formed the centre of farming estates which produced food crops, timber and animal products such as leather and wool. The main rooms in a villa had mosaic floors and were decorated with wall paintings. Pottery production was highly developed in the Roman period and standardised shapes were produced quickly and in large numbers. Most ordinary household pots were multi-purpose containers used for storing, preparing and cooking food. These were made locally wherever suitable clay was available. Finer decorative pottery, such as Samian ware, was used as tableware, and was made in only a few places and traded over wide areas. Wine, sauces and dried fruit were imported in large pottery amphorae while cooking ingredients were puréed in specially designed bowls (mortaria) to produce blends of flavours. Most clothes in Roman Britain were made from woollen or linen fabric. The toga -a single piece of cloth worn over a tunic could be worn by every free-born citizen. However, it was cumbersome and only wealthy Roman men regularly wore one. Most people dressed in a simple tunic. Women wore a stola (long tunic) with a palla (shawl) around the shoulders. Pins and brooches were used to fasten both men and women's clothes and were highly decorative. In Britain the Roman army played an important role in maintaining peace, and from AD 100 around 50,000 troops were stationed in the province. As well as military training, the army constructed buildings and roads. Military documents and letters from Vindolanda, near Hadrian’s Wall, reveal details of the administrative activities of a Roman fort. Civilian settlements developed around forts and trading took place with the local people. Control of particular regions was strengthened by forts, mostly in Wales, northern England and Scotland. A typical fort was rectangular in shape, surrounded by ditches and a wall and divided into blocks by a grid of streets. The headquarters building lay at the centre of the fort. Other buildings included officers’ houses, a bath-house, storage facilities and barracks. Although Latin was the official language in the West of the Roman Empire (Greek in the East) many British people would have continued to use their native tongue. Contact with the Roman administrative and legal systems would probably have given many people a basic spoken understanding of Latin even if they could not read or write. Roman temples were a place for people to pray to the gods, make offerings and take part in religious festivals. Roman houses would often have a small shrine used for worshipping protective household gods, known as the lares, and honouring family ancestors. Local British gods and goddesses were included in the Roman religion. During the reign of the emperor Tiberius (AD 1437), the Christian faith, based on the teachings of Jesus Christ, spread across the empire. Early Christians were often persecuted for their beliefs because they refused to worship the emperor as a god. Then, in AD 313, the emperor Constantine ordered complete freedom of worship for all religions, including Christianity. However, it was not until AD 392, under the emperor Theodosius, that Christianity became the official religion of the Roman empire and all the temples to the Roman gods and goddesses were closed. The disintegration of Roman Britain began with the revolt of Magnus Maximus in AD 383. After living in Britain as military commander for twelve years, he was proclaimed Emperor by his troops and took a large part of the British Roman garrison to the Continent where he dethroned the emperor Gratian, before being killed by the Emperor Thedosius in AD 388. The remaining Roman legions began to withdraw from Britain at the end of the fourth century as the need to protect Rome itself from invading forces grew. As part of the east coast defence, a command was established under the Count of the Saxon Shore, and a fleet was organized to control the Channel and the North Sea. A letter of AD 410 from the Emperor Honorius told the towns of Britain to organize their own defences from that time on. Anglo-Saxons Germanic auxiliary troops had been used for centuries by Rome and that presence in Roman Britain would have facilitated any migration. Graves and settlements suggest that the British population was not killed or displaced, but rather came to adopt Anglo-Saxon culture. The extent of Anglo-Saxon migration seems to have differed considerably across England. Over time the different Germanic peoples formed a unified cultural and political group. By the reign of king Alfred (AD 871-899) a number of Anglo-Saxon kingdoms existed which developed into the kingdom of England in the 10th century. Roman soldiers Teachers notes This activity requires the pupils to look closely at the Roman Army (Cases 6, 8 and 9) as well as the legionary tombstones opposite the Julius Classicianus Tomb. Using the evidence listed below they should be able to indicate whether they agree or disagree with each of the statements. 1. Agree The boots in case 6 have hobnails 2. Disagree There are three tombstones from Lincoln with inscriptions which tells about Gaius Saufeius who originally came from Heraclea in modern Macedonia, Titus Valerius Pudens who originally came from Savaria in Hungary and Gaius Julius Calenus who came from Lyons in Gaul (France). 3. Agree Roman soldiers were paid in coin. This is the main way that coinage got into general circulation. The Bredgar Hoard in case 9 is thought to have been an officer’s pay. 4. Disagree The helmets in cases 6 and 8 include protection for the back of the neck and both cheeks. 5. Agree Daggers are displayed in case 6. 6. Disagree Case 9 shows tiles made by Legio IX and Legio XX, and one by the Classis Britannica, the British Fleet. 7. Agree There were two lighthouses at Dover, the picture in case 9 shows the surviving one. Dover was a base for the British Fleet. 8. Disagree Two mouthpieces for trumpets are shown in case 9. Trumpets and horns were used on campaigns and in the fort for reveille and changing guards. Roman soldiers Gallery sheet Working in a small group, find cases 6, 8 and 9 which all contain material about the Roman army and the group of soldiers’ tombstones which are on open display. Study the objects carefully and then decide which of the following statements you agree with and which you disagree with. Circle your answer. 1. The boots which Roman soldiers wore had nails on the bottom. Agree / Disagree 2. Roman soldiers who died in Britain were taken home to be buried. Agree / Disagree 3. Roman soldiers got their pay in coins. Agree / Disagree 4. A Roman soldier’s helmet only protected the top of the head. Agree / Disagree 5. Roman soldiers carried daggers. Agree / Disagree 6. Roman soldiers did not know how to make roof tiles. Agree / Disagree 7. The Roman navy had lighthouses. Agree / Disagree 8. The Roman army did not have trumpeters. Agree / Disagree Off to work in Roman Britain Teachers notes This activity is aimed at looking for the tools of the trade, rather than finished products. Case 16 (unless otherwise mentioned) is the best source for the activity, with the following: Metal Worker: numbers 1-4: hammerheads, tongs, file, chisel and Corbridge pottery plaque of a Blacksmith; number 28: field anvil in farming tools Builder: plenty of building materials in the right-hand half of the case: box flue tiles, hypocaust tiles, imbrex tiles, tegula tiles, water pipe, mosaic cubes (tesserae), window grille, window glass, hinges, locks, taps, wall-plaster, stone inlay. To the right of Case 16 is the Meonstoke Wall Cook: Eating and drinking section at left-hand end of case 16 includes cooking utensils whilst further along (numbers 35-40) are knives, a gridiron, a cauldron chain, a frying pan, a flesh fork, spoons and bronze pans. Case 21: Mortaria for grinding/mixing food, cheese-press and black-burnished (shiny) pottery commonly used for cooking Carpenter: numbers 5-9: chisels and gouge; numbers 14-16: punch and drill-bit, draw-knife and float; numbers 17-18: adzes amongst the farming tools. Farmer: numbers 17-31: axes, adzes, ploughshare, coulter (blade from plough), spade, hoe, sickle, pruning-hook, bill-hook, rakehead, wool-comb & field anvil. Shoe maker/cobbler: number 12 a cobbler’s last (for making shoes on); number 13 an awl for punching leather. Army secretary: Case 2: Vindolanda tablet display of a folding notebook; styli, tablets and inkpot in Literacy display. Ink on wood, and stylus on wax would have been used. Back at school, it would be interesting to compare these trades and their tools with modern equivalents. Many modern tools are quite similar to Roman ones. Off to work in Roman Britain Gallery sheet Look round the gallery and for each of the job listed below, find and record an object which shows that the job was done in Britain in Roman times. metal worker carpenter builder farmer cook shoe maker And finally a difficult extra one - can you find anything to show the job of an army secretary ? Roman buildings Teachers notes Although archaeologists often find the foundations and floors of Roman buildings in Britain, upper parts of buildings are very rare. Roman buildings were a hardy source of ready worked building materials and were often used to construct a later building nearby. The British Museum has a rare example of Roman walling from a Romano-British agricultural building which was excavated near Meonstoke, Hampshire in 1989. The wall was constructed in the early fourth century AD and is part of the façade of an aisled barn-like building on a villa estate. It collapsed some time after AD 353, as that is the latest date of the coins found underneath. Archaeologists have been able to reconstruct the whole building in great detail from the study of the remains and where they lay. The design, with clerestory windows and a blind arcade above is elaborate and colourful, in the late Antique taste. The greenstone capitals are of the Ionic order, a volute just surviving on the right-hand example. Flints are used to create a rusticated effect, and there were projecting tile cornices over both the windows and arcade. The holes cut through the façade (by this time laying flat on the ground) mark the foundations for a wooden structure of the early Anglo-Saxon period, erected in the fifth or sixth centuries AD. Roman buildings Gallery sheet Find the section of Roman wall from Meonstoke, Hampshire (corner next to case 16). Study it carefully and then match the labels below to the correct part of the wall in the picture. There is some information below the picture to help you work out which material is which. flint clay tile mortar greenstone plaster Flint is a whitish stone which when broken is shiny black inside Mortar is a type of pale cement which is used to join things together. Clay tiles are red and were sometimes piled one on top of another in the wall of a building. Greenstone could be cut into different shapes and used as decoration in a wall. Plaster was a white mixture used to make a smooth surface on a wall. What different shapes can you see in the design of the wall ? Write or draw them in this box. Animals in Roman Britain Teachers notes The objectives of this activity are: To encourage pupils to search for evidence across a wide range of objects and materials. To identify which animals the Romans hunted or farmed. To develop awareness of the sources of animal based food available in Roman Britain. Checklist of animals Hare: case 23 Hoxne pepper pot; case 11 enamelled brooch; case 22 colour-coated ware pot – hunting scene. Horse: case 8 cavalry items; case 11 enamelled brooch; case 6 chariot racing scene on pot; case 15 statuettes; case 10 riders shown on coins; the Kirby Thore tombstone – on wall behind Julius Classicianus tomb; case 22- rim of silver bowl. Goat: case 15 statuette; case 20 statuette and bones; case 22 on silverware; case 23 Hoxne pepperpot; case 16 painted on wall plaster. Sheep: case 20 statuette and bones; case 7 hoof imprint in a tile from the settlement at Stonea. Boar: case 9 Legio XX antefix; case 15 statuette. Dog: case 7 imprint in Stonea tile; case 16 Ashstead villa flue tile; cases 7 & 21 dogs hunting on vases; case 15 dog-like statuette; case 17 Corbridge Lanx. Cockerel: cases 15 & 20 statuettes; case 20 bones; case 11 enamelled brooch Deer: cases 7 & 21 being hunted on vases; case 22 rim of silver bowl. Bear: case 22 rim of silver bowl. Bull/Ox: case 15 statuette; case 22 rim of silver bowl; case 19 image of Mithras and the Bull; case 6 on shield boss; case 17 Corbrodge Lanx. Hare, boar, deer and bear were all wild animals The rest were farmed animals. Animals in Roman Britain Gallery sheet Look round the gallery carefully for examples of different animals. Look in particular for evidence that the Romans either kept or knew about the animals listed below and record this on the table. If you can tell, circle if the animal was hunted or kept on a farm. animal hare evidence hunted or kept? hunted kept horse hunted kept goat hunted kept sheep hunted kept boar pig / wild hunted kept dog hunted kept cockerel hunted kept deer hunted kept bear hunted kept bull / ox hunted kept What are they made from ? Teachers notes It would be helpful to brief pupils on the following materials before the visit: Wood -most wooden objects do not survive Bone -often used for tools Leather - most does not survive Jet -dark black stone used in jewellery Gold Silver Copper – generally brown or green Bronze (copper and tin) – generally brown or green; sometimes plated with tin Brass – golden or green Lead – dull silvery colour Pewter (tin and lead) – dull silvery colour Iron – black, brown to steel colour List of objects, stating materials and where they can be found: Cases Pins and needles – bone and bronze 2 and 7 Bracelet – gold, silver and jet 11 and 23 Note book – folded wooden leaves, or joined tablets 2 and 3 Bowl – silver, bronze, pewter, pottery & glass 7, 16, 17, 18, 21, 22 and 23 Mirror – tinned bronze 4 and 14 Shoes – leather; some had iron hob-nails 1, 3, 6 and 7 Knife – iron with wood/bone handles Comb – bone 16 4 It is very interesting to compare ancient objects with their modern counterparts. Pupils could do work which involves illustrating ancient and modern tools, comparing their materials and effectiveness. It is fascinating to see how some of the objects are so similar. What Gallery sheet are they made Here are eight objects from Roman Britain. Look round the Roman Britain gallery carefully to find them. of? Fill in the information. Object pins and needles Made out of? What would a modern version be made out of? Is the Roman version better, worse or the same? better worse the same bracelet better worse the same note book better worse the same bowl better worse the same mirror better worse the same shoes better worse the same knife better worse the same comb better worse the same Roman Teachers notes tombstones Roman tombstones often had objects or symbols carved on them, sometimes shown the deceased as they wanted to be remembered and usually carried an inscription giving details including the person’s name, age at death, date of death and sometimes their occupation or family connections. Tombstone of Gaius Julius Alpinus Classicianus 1st century AD, found in Trinity Square, London This is the reconstructed tombstone of Gaius Julius Alpinus Classicianus a member of the Gallic aristocracy. Nero (reigned AD 54-68) appointed Classsicianus as the procurator (finance minister) of Britain after the revolt of the Iceni led by Queen Boudica in AD 60-61. His job was to correct the financial abuses that had been an important cause of the rebellion. In late Roman times pieces of the tombstone were re-used in the hurried construction of one of the bastions that protected the walls of Roman London. Tombstone of a soldier's daughter 2nd-4th centuries AD, found near the site of the Roman fort at Kirkby Thore, Cumbria The name of the woman is missing from this broken tombstone. However, the remaining part of the inscription in the lower right corner tells us that she was the daughter of a military standardbearer (imaginifer) called Crescens. The scene shows a funeral banquet, a common motif on the tombstones of Romano-British women. The dead woman reclines on a couch holding a fancy two-handled cup or goblet. A servant passes her food from a decorative threelegged table. Framing the scene are a number of motifs symbolising death and the Afterlife: the gaping head on the right probably represented alldevouring death; the pine-cone, above, was a symbol of immortality, and the rosette, next to it, was a symbol of fertility in the Afterlife. Tombstone of Volusia Faustina and Claudia Catiotua 3rd century AD found in Lincoln The woman depicted in the left-hand portrait bust, wearing a necklace, is Volusia Faustina. She was the wife of Aurelius Senecio, a town councillor at Lincoln, who set up the monument after she died at the age of 26. The second woman is Claudia Catiotua. It is not clear what her relationship with Volusia was, but she may have been her mother, or perhaps her successor as the second wife of Aurelius Senecio. She lived longer than Volusia, over sixty years, according to the inscription. Roman Gallery sheet tombstones Find these three Roman tombstones, look at them carefully and then answer the questions. Gaius Julius Alpinus Classicianus Which language inscription ? is used for the carved Why do you think this tombstone is so large ? A soldier’s daughter What is in front of her? What is she holding? What is she lying on ? Where do you think this meal is happening? Volusia Faustina and Claudia Catiotua What are the women shown wearing ? What do you think the relationship between the two women was ? Why have portraits tombstone ? Design Teachers notes your own of their faces Roman on the tombstone This activity can either follow on from the last suggested activity with tombstones or can be used independently. The aim of the activity to encourage the pupils to use the tombstones displayed in the gallery as a source of information to help them design their own Roman tombstone. All the information they record on the gallery sheet can be used back at school to support the pupils as they design their own Roman tombstone – including all the key elements they observed on the Museum examples. You may also find it useful to take photographs of the gallery tombstones for reference purposes later (particularly with regard to shape and colour which are not recorded specifically by the pupils) two and some of the tombstones can be found in the Explore section of the British Museum website at www.thebritishmuseum.ac.uk/explore Design Gallery sheet your own Roman tombstone Look carefully at the tombstones on display in the gallery and collect some ideas which will help you to design your own Roman tombstone back at school. Practise some Roman style writing here. Some stones have a carving. Do a rough sketch here. Draw some Roman symbols. There is information about symbols below. Who put up the tombstone to you? Husband? Wife? Children? Exslaves? How old were you when you died? Make sure you use Roman numerals! What is your homeland? People in Britain came from across the empire. If you were a soldier, how long did you serve for? If not a soldier, what was your job or occupation? Stars – represent wealth or becoming a god or goddess in the next world. Dolphins –represent the sea voyage to the Land of the Dead Pine cones – represent life after death (new plants growing from dry old seeds) Further resources Printed material BM Pocket Timeline of Ancient Rome by Katharine Wiltshire BM Illustrated Encyclopaedia of Ancient Rome by Mike Corbishley BM Pocket Dictionary of Roman Emperors by Roberts Paul BM Pocket Dictionary of Greek and Roman Gods and Goddesses by Richard Woff BM Timeline of the Ancient World by Wiltshire Katharine British Museum web resources British Museum website www.thebritishmuseum.ac.uk Explore Adults www.thebritishmuseum.ac.uk/explore Explore Children www.thebritishmuseum.ac.uk/explore The Ancient World www.ancientcivilizations.co.uk Other useful websites Portable Antiquities Scheme www.finds.org.uk Museum of London www.museumoflondon.org.uk English Heritage heritage.org.uk www.english- Fishbourne Roman Palace www.sussexpast.co.uk