* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Melody In Carnatic Music

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

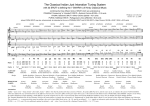

Melody In Carnatic Music – Part 1 By Kiranavali Vidyasankar As I said in my introduction, Carnatic music is ruled by the Sanskrit saying, Srutir mata, layah pita meaning, Melody is mother, Rhythm is father. In the next few columns, I shall deal with the first part of the saying, Srutir mata, or the melodic aspects. Any lover of Indian music would have definitely come across the word Raga. Needless to say, this concept is a very ancient one. But what exactly is it and how did it evolve? Before we go into it, we need to know some basic stuff. Let's start with the skeleton of the Raga, which are the notes or swara-s, as they are called in Indian music. Well, like most systems of music across the world, Carnatic music also has seven basic notes, the Sapta (seven) Swaras (notes) in an octave. They are Shadja (Sa), Rishabha (Ri), Gandhara (Ga), Madhyama (Ma), Panchama (Pa), Dhaivata (Dha) and Nishada (Ni). While Sa and Pa are the constant notes that remain fixed in any given pitch, the rest of the five notes have variable values of two each. That gives us a total of twelve notes or swarasthana-s in the octave (sthana literally means place or position). Isn't it amazing that different civilizations across the globe have arrived at the same results through the centuries? Anyway, here's what makes Carnatic music different. Although there are twelve swarasthana-s, they are called by sixteen different names. This obviously means that there is some overlapping of the notes. This probably happened only to accommodate peculiar ragas like Nata or Varali which already existed before all these theories were propounded. So it was not with a view to be different that this idea was conceived, but only to properly classify these differences. Here's a table of the sixteen notes with their Hindustani equivalents: Carnatic swaras Hindustani swaras Shadja - Sa Shad - Sa Shuddha Rishabha – Ri 1 Komal Rishabh Chatusruti Rishabha – Ri 2 Shudh Rishabh Shatsruti Rishabha – Ri 3 Komal Gandhar Shuddha Gandhara – Ga 1 Shudh Rishabh Sadharana Gandhara – Ga 2 Komal Gandhar Antara Gandhara – Ga 3 Shudh Gandhar Shuddha Madhyama – Ma 1 Shudh Madhyam Prati Madhyama – Ma 2 Teevr Madhyam Panchama Pancham Shuddha Dhaivata – Da 1 Komal Dhaivat Chatusruti Dhaivata – Da 2 Shudh Dhaivat Shatsruti Dhaivata – Da 3 Komal Nishad Shuddha Nishada – Ni 1 Shudh Dhaivat Kaisika Nishada – Ni 2 Komal Nishad Kakali Nishada – Ni 3 Shudh Nishad Now, from the table above, we can see that the sixteen different notes have been arrived at by increasing the number of variables for the notes Ri, Ga, Da and Ni from two to three. So we still have one Sa and Pa, two Ma-s but three Ri-s, Ga-s, Da-s and Ni-s. The interesting thing here is that Chatusrtui Rishabha (Ri 2) and Suddha Gandhara (Ga 1) share the same place values. i.e., you would render them in the same place, but just call them by different names depending upon the context. The same thing happens in the case of Shatsruti Rishabha (Ri 3) and Sadharana Gandhara (Ga 2); Chatusruti Dhaivata (Da 2) and Suddha Nishada (Ni 1); and Shatsruti Dhaivata (Da 3) and Kaisika Nishada (Ni 2). This unique feature is more obvious from the table of the Hindustani notes where Shudh Rishabh, Komal Gandhar, Shudh Dhaivat and Komal Nishad occur twice. Simply put, Ri 2 = Ga 1 Ri 3 = Ga 2 Da 2 = Ni 1 Da 3 = Ni 2 This can be illustrated better with the help of the adjoining diagram. The notes on the left are the twelve basic swarasthana-s and those given on the right are the four extra notes. Why the sixteen names? As said earlier, ancient Ragas like Nata (Ri 3 and Da 3) and Varali (Ga 1) use relatively uncommon notes. In order to classify them properly, these notes had to be given a place. There are a few simple rules which determine how the overlapping notes are used: When Suddha Rishabha (Ri 1) and Chatusruti Rishabha (Ri 2) occur consecutively in the same raga, Ri 2 is sung as Ga 1 (Suddha Gandhara). When Sadharana Gandhara (Ga 2) and Antara Gandhara (Ga 3) occur consecutively, then Ga 2 is sung as Ri 3 (Shatsruti Rishabha). Similarly, when Suddha Dhaivata (Da 1) and Chatusruti Dhaivata (Da 2) occur consecutively, then Da 2 is sung as Ni 1 (Suddha Nishada). And when Kaisika Nishada (Ni 2) and Kakali Nishada (Ni 3) occur consecutivesly, Ni 2 is sung as Shatsruti Dhaivata (Da 3). Of course, music being an art, there are cases when these rules are waived. However, we will come to that later. In my next article, I shall talk about how the 16 notes combine to give scales and Ragas.