* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

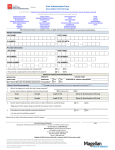

Download 2017 Magellan Care Guidelines

Dissociative identity disorder wikipedia , lookup

Substance dependence wikipedia , lookup

Critical Psychiatry Network wikipedia , lookup

Cases of political abuse of psychiatry in the Soviet Union wikipedia , lookup

Classification of mental disorders wikipedia , lookup

Anti-psychiatry wikipedia , lookup

Deinstitutionalisation wikipedia , lookup

Psychiatric rehabilitation wikipedia , lookup

David J. Impastato wikipedia , lookup

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders wikipedia , lookup

Psychiatric and mental health nursing wikipedia , lookup

Political abuse of psychiatry wikipedia , lookup

History of mental disorders wikipedia , lookup

Political abuse of psychiatry in Russia wikipedia , lookup

Mental health professional wikipedia , lookup

Mental status examination wikipedia , lookup

Moral treatment wikipedia , lookup

Pyotr Gannushkin wikipedia , lookup

History of psychiatry wikipedia , lookup

History of psychiatric institutions wikipedia , lookup

Abnormal psychology wikipedia , lookup

Psychiatric hospital wikipedia , lookup