* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download The Pyroelectric Fire alarm

Ground (electricity) wikipedia , lookup

Variable-frequency drive wikipedia , lookup

Pulse-width modulation wikipedia , lookup

Power engineering wikipedia , lookup

Power inverter wikipedia , lookup

Flexible electronics wikipedia , lookup

Electrical substation wikipedia , lookup

History of electric power transmission wikipedia , lookup

Electronic engineering wikipedia , lookup

Negative feedback wikipedia , lookup

Electrical ballast wikipedia , lookup

Stray voltage wikipedia , lookup

Regenerative circuit wikipedia , lookup

History of the transistor wikipedia , lookup

Voltage optimisation wikipedia , lookup

Current source wikipedia , lookup

Voltage regulator wikipedia , lookup

Power MOSFET wikipedia , lookup

Integrated circuit wikipedia , lookup

Power electronics wikipedia , lookup

Surge protector wikipedia , lookup

Alternating current wikipedia , lookup

Two-port network wikipedia , lookup

Schmitt trigger wikipedia , lookup

Buck converter wikipedia , lookup

Mains electricity wikipedia , lookup

Switched-mode power supply wikipedia , lookup

Resistive opto-isolator wikipedia , lookup

Network analysis (electrical circuits) wikipedia , lookup

The Pyroelectric Fire alarm

CONTENTS

PAGE NOS

1. ABSTRACT

2. INTRODUCTION

3. MATERIALS REQUIRED

4. CIRCUIT DESCRIPTION

5. COMPONENTS

6. WORKING OF THE CIRCUIT

7. RESULT

8. CONCLUSION

9. REFERENCES

ABSTRACT

The circuit of Pyroelectric Fire Alarm is an Ultra sensitive fire sensor that exploits

the direct Piezo electric property of the Piezo element to detect fire. An ordinary

Piezo element of Buzzer is used as the Fire sensor. The Lead Titanate Zirconate

crystals in the Piezo element have the property to deform and generate an electric

potential when heated. This property is exploited in the circuit to make an ultra

sensitive Fire Alarm. Unlike Thermister based Fire sensors, this circuit can detect a

10 degree rise in temperature and gives a warning alarm even before the fire

breaks. If the temperature continues due to fire, it automatically operates a relay

which can be used to switch on a Water sprayer or Solenoid pump to spray water

or fire ceasing foam.

INTRODUCTION

Electronics is a very vast field embracing almost all walks of human

endeavor. The word electronics was defined by the institution of Radio Engineers

as follows: The field of science and engineering which deals with electron devices

and their utilization. Electron devices are those devices where current flow is due

to the controlled flow of charge carriers through a gas, a vaccum or a

semiconductor.

Electronics is the branch of science and technology that deals with electrical

circuits involving active electrical components such as vacuum tubes, transistors,

diodes and integrated circuits. The nonlinear behavior of these components and

their ability to control electron flows makes amplification of weak signals possible,

and is usually applied to information and signal processing.

Electronics is distinct from electrical and electro-mechanical science and

technology, which deals with the generation, distribution, switching, storage and

conversion of electrical energy to and from other energy forms using wires,

motors, generators, batteries, switches, relays, transformers, resistors and other

passive components. Today, most electronic devices use semiconductor

components to perform electron control. The study of semiconductor devices and

related technology is considered a branch of solid state physics, whereas the design

and construction of electronic circuits to solve practical problems come under

electronics engineering. Until recently, electronics was considered an integral part

of Physics, but due to tremendous advancements during the last few decades, thus

it has now gained its rightful place.

LIST OF COMPONENTS IN THE CIRCUIT

The components used in the circuit are given in the following table:

Components

Resistors

Capacitors Transistors

VR1- 22K C2- 10p

R3-1K

C3- 22µ

R4-1K

R5-1K

Specifications

R6-1M

R7-1M

R8-1K

The other

T1- BC 547

T2- BC 547

components are:

(1) Piezo element

(2) Piezo Buzzer

(3) Light emitting Diode (LED2)

(4) 9 V Battery

(5) Printed Circuit Board(PCB)

Integrated

Chip

IC1-CA

3130

IC2CD 4060

Diode

Relay

D7OA71

RL112V,200Ω

D8IN4148

D9IN4OO7

Electronic devices and components

An electronic component is any physical entity in an electronic system used to

affect the electrons or their associated fields in a desired manner consistent with

the intended function of the electronic system. Components are generally intended

to be connected together, usually by being soldered to a printed circuit board

(PCB), to create an electronic circuit with a particular function (for example an

amplifier, radio receiver, or oscillator). Components may be packaged singly or in

more complex groups as integrated circuits. Some common electronic components

are capacitors, inductors, resistors, diodes, transistors, etc. Components are often

categorized as active (e.g. transistors and thyristors) or passive (e.g. resistors and

capacitors).

Resistors

A resistor is a two-terminal passive electronic component which implements

electrical resistance as a circuit element. When a voltage V is applied across the

terminals of a resistor, a current I will flow through the resistor in direct proportion

to that voltage. The reciprocal of the constant of proportionality is known as the

resistance R, since, with a given voltage V, a larger value of R further “resists" the

flow of current I as given by Ohm's law:

Resistors are common elements of electrical networks and electronic circuits and

are ubiquitous in most electronic equipment. Practical resistors can be made of

various compounds and films, as well as resistance wire (wire made of a highresistivity alloy, such as nickel-chrome). Resistors are also implemented within

integrated circuits, particularly analog devices, and can also be integrated into

hybrid and printed circuits.

The electrical functionality of a resistor is specified by its resistance: common

commercial resistors are manufactured over a range of more than 9 orders of

magnitude. When specifying that resistance in an electronic design, the required

precision of the resistance may require attention to the manufacturing tolerance of

the chosen resistor, according to its specific application. The temperature

coefficient of the resistance may also be of concern in some precision applications.

Practical resistors are also specified as having a maximum power rating which

must exceed the anticipated power dissipation of that resistor in a particular circuit:

this is mainly of concern in power electronics applications. Resistors with higher

power ratings are physically larger and may require heat sinking. In a high voltage

circuit, attention must sometimes be paid to the rated maximum working voltage of

the resistor.

The series inductance of a practical resistor causes its behavior to depart from

ohms law; this specification can be important in some high-frequency applications

for smaller values of resistance. In a low-noise amplifier or pre-amp the noise

characteristics of a resistor may be an issue. The unwanted inductance, excess

noise, and temperature coefficient are mainly dependent on the technology used in

manufacturing the resistor. They are not normally specified individually for a

particular family of resistors manufactured using a particular technology. A family

of discrete resistors is also characterized according to its form factor, that is, the

size of the device and position of its leads (or terminals) which is relevant in the

practical manufacturing of circuits using them.

Variable resistors

Adjustable resistors

A resistor may have one or more fixed tapping points so that the resistance can be

changed by moving the connecting wires to different terminals. Some wire wound

power resistors have a tapping point that can slide along the resistance element,

allowing a larger or smaller part of the resistance to be used.

Where continuous adjustment of the resistance value during operation of

equipment is required, the sliding resistance tap can be connected to a knob

accessible to an operator. Such a device is called a rheostat and has two terminals.

Potentiometers

A common element in electronic devices is a three-terminal resistor with a

continuously adjustable tapping point controlled by rotation of a shaft or knob.

These variable resistors are known as potentiometers when all three terminals are

present, since they act as a continuously adjustable voltage divider. A common

example is a volume control for a radio receiver.

Accurate, high-resolution panel-mounted potentiometers (or "pots") have

resistance elements typically wire wound on a helical mandrel, although some

include a conductive-plastic resistance coating over the wire to improve resolution.

These typically offer ten turns of their shafts to cover their full range. They are

usually set with dials that include a simple turns counter and a graduated dial.

Electronic analog computers used them in quantity for setting coefficients, and

delayed-sweep oscilloscopes of recent decades included one on their panels.

Resistance decade boxes

A resistance decade box or resistor substitution box is a unit containing resistors of

many values, with one or more mechanical switches which allow any one of

various discrete resistances offered by the box to be dialed in. Usually the

resistance is accurate to high precision, ranging from laboratory/calibration grade

accuracy of 20 parts per million, to field grade at 1%. Inexpensive boxes with

lesser accuracy are also available. All types offer a convenient way of selecting

and quickly changing a resistance in laboratory, experimental and development

work without needing to attach resistors one by one or even stock each value. The

range of resistance provided, the maximum resolution, and the accuracy

characterize the box. For example, one box offers resistances from 0 to 24 meg

ohms, maximum resolution 0.1 ohm, accuracy 0.1%.

Capacitor

A capacitor (formerly known as condenser) is a device for storing electric charge.

The forms of practical capacitors vary widely, but all contain at least two

conductors separated by a non-conductor. Capacitors used as parts of electrical

systems, for example, consist of metal foils separated by a layer of insulating film.

A capacitor is a passive electronic component consisting of a pair of conductors

separated by a dielectric (insulator). When there is a potential difference (voltage)

across the conductors, a static electric field develops across the dielectric, causing

positive charge to collect on one plate and negative charge on the other plate.

Energy is stored in the electrostatic field. An ideal capacitor is characterized by a

single constant value, capacitance, measured in farads. This is the ratio of the

electric charge on each conductor to the potential difference between them.

Capacitors are widely used in electronic circuits for blocking direct current while

allowing alternating current to pass, in filter networks, for smoothing the output of

power supplies, in the resonant circuits that tune radios to particular frequencies

and for many other purposes.

The capacitance is greatest when there is a narrow separation between large areas

of conductor; hence capacitor conductors are often called "plates", referring to an

early means of construction. In practice the dielectric between the plates passes a

small amount of leakage current and also has an electric field strength limit,

resulting in a breakdown voltage, while the conductors and leads introduce an

undesired inductance and resistance

Diode

In electronics, a diode is a two-terminal electronic component that conducts

electric current in only one direction. The term usually refers to a semiconductor

diode, the most common type today. This is a crystalline piece of semiconductor

material connected to two electrical terminals.[1] A vacuum tube diode (now little

used except in some high-power technologies) is a vacuum tube with two

electrodes: a plate and a cathode.

The most common function of a diode is to allow an electric current to pass in one

direction (called the diode's forward direction) while blocking current in the

opposite direction (the reverse direction). Thus, the diode can be thought of as an

electronic version of a check valve. This unidirectional behavior is called

rectification, and is used to convert alternating current to direct current, and to

extract modulation from radio signals in radio receivers.

However, diodes can have more complicated behavior than this simple on-off

action. This is due to their complex non-linear electrical characteristics, which can

be tailored by varying the construction of their P-N junction. These are exploited in

special purpose diodes that perform many different functions. For example,

specialized diodes are used to regulate voltage (Zener diodes), to electronically

tune radio and TV receivers (varactor diodes), to generate radio frequency

oscillations (tunnel diodes), and to produce light (light emitting diodes). Tunnel

diodes exhibit negative resistance, which makes them useful in some types of

circuits.

Operational amplifier

An operational amplifier ("op-amp") is a DC-coupled high-gain electronic

voltage amplifier with a differential input and, usually, a single-ended output. An

op-amp produces an output voltage that is typically hundreds of thousands times

larger than the voltage difference between its input terminals.

Operational amplifiers are important building blocks for a wide range of electronic

circuits. They had their origins in analog computers where they were used in many

linear, non-linear and frequency-dependent circuits. Their popularity in circuit

design largely stems from the fact that characteristics of the final elements (such as

their gain) are set by external components with little dependence on temperature

changes and manufacturing variations in the op-amp itself.

Op-amps are among the most widely used electronic devices today, being used in a

vast array of consumer, industrial, and scientific devices. Many standard IC opamps cost only a few cents in moderate production volume; however some

integrated or hybrid operational amplifiers with special performance specifications

may cost over $100 US in small quantities. Op-amps may be packaged as

components, or used as elements of more complex integrated circuits.

The op-amp is one type of differential amplifier. Other types of differential

amplifier include the fully differential amplifier (similar to the op-amp, but with

two outputs), the instrumentation amplifier (usually built from three op-amps), the

isolation amplifier (similar to the instrumentation amplifier, but with tolerance to

common-mode voltages that would destroy an ordinary op-amp), and negative

feedback amplifier (usually built from one or more op-amps and a resistive

feedback network).

Circuit notation

Circuit diagram symbol for an op-amp

The circuit symbol for an op-amp is shown to the right, where:

: Non-inverting input

: inverting input

: Output

: Positive power supply

: Negative power supply

The power supply pins (

and ) can be labeled in different ways (See IC

power supply pins). Despite different labeling, the function remains the same — to

provide additional power for amplification of the signal. Often these pins are left

out of the diagram for clarity, and the power configuration is described or assumed

from the circuit.

Operation

The amplifier's differential inputs consist of a input and a input, and ideally

the op-amp amplifies only the difference in voltage between the two, which is

called the differential input voltage. The output voltage of the op-amp is given by

the equation,

where,

is the voltage at the non-inverting terminal, is the voltage at the

inverting terminal and AOL is the open-loop gain of the amplifier. (The term

"open-loop" refers to the absence of a feedback loop from the output to the input).

Typically the op-amp's very large gain is controlled by negative feedback, which

largely determines the magnitude of its output ("closed-loop") voltage gain in

amplifier applications, or the transfer function required (in analog computers).

Without negative feedback, and perhaps with positive feedback for regeneration,

an op-amp acts as a comparator. High input impedance at the input terminals and

low output impedance at the output terminal(s) are important typical

characteristics.

With no negative feedback, the op-amp acts as a comparator. The inverting input is

held at ground (0 V) by the resistor, so if the Vin applied to the non-inverting input

is positive, the output will be maximum positive, and if Vin is negative, the output

will be maximum negative. Since there is no feedback from the output to either

input, this is an open loop circuit. The circuit's gain is just the GOL of the op-amp.

Adding negative feedback via the voltage divider Rf, Rg reduces the gain.

Equilibrium will be established when Vout is just sufficient to reach around and

"pull" the inverting input to the same voltage as Vin. As a simple example, if Vin =

1 V and Rf = Rg, Vout will be 2 V, the amount required to keep V– at 1 V. Because

of the feedback provided by Rf, Rg this is a closed loop circuit. Its over-all gain

Vout / Vin is called the closed-loop gain ACL. Because the feedback is negative,

in this case ACL is less than the AOL of the op-amp.

The magnitude of AOL is typically very large—10,000 or more for integrated

circuit op-amps—and therefore even a quite small difference between

and

drives the amplifier output nearly to the supply voltage. This is called saturation

of the amplifier. The magnitude of AOL is not well controlled by the

manufacturing process, and so it is impractical to use an operational amplifier as a

stand-alone differential amplifier. If predictable operation is desired, negative

feedback is used, by applying a portion of the output voltage to the inverting input.

The closed loop feedback greatly reduces the gain of the amplifier. If negative

feedback is used, the circuit's overall gain and other parameters become

determined more by the feedback network than by the op-amp itself. If the

feedback network is made of components with relatively constant, stable values,

the unpredictability and inconstancy of the op-amp's parameters do not seriously

affect the circuit's performance.

If no negative feedback is used, the op-amp functions as a switch or comparator.

Positive feedback may be used to introduce Hysteresis or oscillation.

Ideal and real op-amps

An ideal op-amp is usually considered to have the following properties, and they

are considered to hold for all input voltages:

Infinite open-loop gain (when doing theoretical analysis, a limit may be taken as

open loop gain AOL goes to infinity).

Infinite voltage range available at the output (vout) (in practice the voltages

available from the output are limited by the supply voltages

and ). The

power supply sources are called rails.

Infinite bandwidth (i.e., the frequency magnitude response is considered to be flat

everywhere with zero phase shift).

Infinite input impedance (so, in the diagram,

from to ).

, and zero current flows

Zero input current (i.e., there is assumed to be no leakage or bias current into the

device).

Zero input offset voltage (i.e., when the input terminals are shorted so that

the output is a virtual ground or vout = 0).

,

Infinite slew rate (i.e., the rate of change of the output voltage is unbounded) and

power bandwidth (full output voltage and current available at all frequencies).

Zero output impedance (i.e., Rout = 0, so that output voltage does not vary with

output current).

Zero noise.

Infinite Common-mode rejection ratio (CMRR).

Infinite Power supply rejection ratio for both power supply rails.

These ideals can be summarized by the two "golden rules":

I. The output attempts to do whatever is necessary to make the voltage difference

between the inputs zero.

II. The inputs draw no current.

The first rule only applies in the usual case where the op-amp is used in a closedloop design (negative feedback, where there is a signal path of some sort feeding

back from the output to the inverting input). These rules are commonly used as a

good first approximation for analyzing or designing op-amp circuits. In practice,

none of these ideals can be perfectly realized, and various shortcomings and

compromises have to be accepted. Depending on the parameters of interest, a real

op-amp may be modeled to take account of some of the non-infinite or non-zero

parameters using equivalent resistors and capacitors in the op-amp model. The

designer can then include the effects of these undesirable, but real, effects into the

overall performance of the final circuit. Some parameters may turn out to have

negligible effect on the final design while others represent actual limitations of the

final performance that must be evaluated.

Transistor

A transistor is a semiconductor device used to amplify and switch electronic

signals. It is made of a solid piece of semiconductor material, with at least three

terminals for connection to an external circuit. A voltage or current applied to one

pair of the transistor's terminals changes the current flowing through another pair

of terminals. Because the controlled (output) power can be much more than the

controlling (input) power, the transistor provides amplification of a signal. Today,

some transistors are packaged individually, but many more are found embedded in

integrated circuits.

The transistor is the fundamental building block of modern electronic devices, and

is ubiquitous in modern electronic systems. Following its release in the early 1950s

the transistor revolutionized the field of electronics, and paved the way for smaller

and cheaper radios, calculators, and computers, among other things.

Importance

The transistor is the key active component in practically all modern electronics,

and is considered by many to be one of the greatest inventions of the twentieth

century. Its importance in today's society rests on its ability to be mass produced

using a highly automated process (semiconductor device fabrication) that achieves

astonishingly low per-transistor costs.

Although several companies each produce over a billion individually packaged

(known as discrete) transistors every year,[10] the vast majority of transistors now

produced are in integrated circuits (often shortened to IC, microchips or simply

chips), along with diodes, resistors, capacitors and other electronic components, to

produce complete electronic circuits. A logic gate consists of up to about twenty

transistors whereas an advanced microprocessor, as of 2011, can use as many as 3

billion transistors (MOSFETs). "About 60 million transistors were built this year

[2002] ... for [each] man, woman, and child on Earth."

The transistor's low cost, flexibility, and reliability have made it a ubiquitous

device. Transistorized mechatronic circuits have replaced electromechanical

devices in controlling appliances and machinery. It is often easier and cheaper to

use a standard microcontroller and write a computer program to carry out a control

function than to design an equivalent mechanical control function.

Usage

The bipolar junction transistor, or BJT, was the most commonly used transistor in

the 1960s and 70s. Even after MOSFETs became widely available, the BJT

remained the transistor of choice for many analog circuits such as simple

amplifiers because of their greater linearity and ease of manufacture. Desirable

properties of MOSFETs, such as their utility in low-power devices, usually in the

CMOS configuration, allowed them to capture nearly all market share for digital

circuits; more recently MOSFETs have captured most analog and power

applications as well, including modern clocked analog circuits, voltage regulators,

amplifiers, power transmitters, motor drivers, etc. The essential usefulness of a

transistor comes from its ability to use a small signal applied between one pair of

its terminals to control a much larger signal at another pair of terminals. This

property is called gain. A transistor can control its output in proportion to the input

signal; that is, it can act as an amplifier. Alternatively, the transistor can be used to

turn current on or off in a circuit as an electrically controlled switch, where the

amount of current is determined by other circuit elements.

The two types of transistors have slight differences in how they are used in a

circuit. A bipolar transistor has terminals labeled base, collector, and emitter. A

small current at the base terminal (that is, flowing from the base to the emitter) can

control or switch a much larger current between the collector and emitter terminals.

For a field-effect transistor, the terminals are labeled gate, source, and drain, and a

voltage at the gate can control a current between source and drain.

The image to the right represents a typical bipolar transistor in a circuit. Charge

will flow between emitter and collector terminals depending on the current in the

base. Since internally the base and emitter connections behave like a

semiconductor diode, a voltage drop develops between base and emitter while the

base current exists. The amount of this voltage depends on the material the

transistor is made from, and is referred to as VBE.

Transistor as a switch

BJT used as an electronic switch, in grounded-emitter configuration.

Transistors are commonly used as electronic switches, both for high-power

applications such as switched-mode power supplies and for low-power applications

such as logic gates.

In a grounded-emitter transistor circuit, such as the light-switch circuit shown, as

the base voltage rises the base and collector current rise exponentially, and the

collector voltage drops because of the collector load resistor. The relevant

equations:

VRC = ICE × RC, the voltage across the load (the lamp with resistance RC)

VRC + VCE = VCC, the supply voltage shown as 6V

If VCE could fall to 0 (perfect closed switch) then Ic could go no higher than VCC

/ RC, even with higher base voltage and current. The transistor is then said to be

saturated. Hence, values of input voltage can be chosen such that the output is

either completely off, or completely on. The transistor is acting as a switch, and

this type of operation is common in digital circuits where only "on" and "off"

values are relevant.

Transistor as an amplifier

Amplifier circuit, common-emitter configuration.

The common-emitter amplifier is designed so that a small change in voltage in

(Vin) changes the small current through the base of the transistor and the

transistor's current amplification combined with the properties of the circuit mean

that small swings in Vin produce large changes in Vout.

Various configurations of single transistor amplifier are possible, with some

providing current gain, some voltage gain, and some both.

From mobile phones to televisions, vast numbers of products include amplifiers for

sound reproduction, radio transmission, and signal processing. The first discrete

transistor audio amplifiers barely supplied a few hundred mill watts, but power and

audio fidelity gradually increased as better transistors became available and

amplifier architecture evolved.

Modern transistor audio amplifiers of up to a few hundred watts are common and

relatively inexpensive.

Buzzer

A buzzer or beeper is an audio signaling device, which may be mechanical,

electromechanical, or piezoelectric. Typical uses of buzzers and beepers include

alarms, timers and confirmation of user input such as a mouse click or

keystrPiezoelectric

Piezoelectric disk beeper

A piezoelectric element may be driven by an oscillating electronic circuit or

other audio signal source, driven with a piezoelectric audio amplifier. Sounds

commonly used to indicate that a button has been pressed are a click, a ring or a

beep.

Light-emitting diode

A light-emitting diode is a semiconductor light source. LEDs are used as

indicator lamps in many devices and are increasingly used for other lighting.

Introduced as a practical electronic component in 1962, early LEDs emitted lowintensity red light, but modern versions are available across the visible, ultraviolet

and infrared wavelengths, with very high brightness.

When a light-emitting diode is forward biased (switched on), electrons are

able to recombine with electron holes within the device, releasing energy in the

form of photons. This effect is called electroluminescence and the color of the light

(corresponding to the energy of the photon) is determined by the energy gap of the

semiconductor. An LED is often small in area (less than 1 mm2), and integrated

optical components may be used to shape its radiation pattern. LEDs present many

advantages over incandescent light sources including lower energy consumption,

longer lifetime, improved robustness, smaller size, faster switching, and greater

durability and reliability. LEDs powerful enough for room lighting are relatively

expensive and require more precise current and heat management than compact

fluorescent lamp sources of comparable output.

Light-emitting diodes are used in applications as diverse as replacements for aviation

lighting, automotive lighting (particularly brake lamps, turn signals and indicators) as well as in

traffic signals. The compact size, the possibility of narrow bandwidth, switching speed, and

extreme reliability of LEDs has allowed new text and video displays and sensors to be

developed, while their high switching rates are also useful in advanced communications

technology. Infrared LEDs are also used in the remote control units of many commercial

products including televisions, DVD players, and other domestic appliances.

The LED consists of a chip of semi conducting material doped with

impurities to create a p-n junction. As in other diodes, current flows easily from the

p-side, or anode, to the n-side, or cathode, but not in the reverse direction. Chargecarriers—electrons and holes—flow into the junction from electrodes with

different voltages. When an electron meets a hole, it falls into a lower energy level,

and releases energy in the form of a photon.

The wavelength of the light emitted, and thus its color depends on the band gap

energy of the materials forming the p-n junction. In silicon or germanium diodes,

the electrons and holes recombine by a non-radiative transition which produces no

optical emission, because these are indirect band gap materials. The materials used

for the LED have a direct band gap with energies corresponding to near-infrared,

visible or near-ultraviolet light.

LED development began with infrared and red devices made with gallium

arsenide. Advances in materials science have enabled making devices with evershorter wavelengths, emitting light in a variety of colors.

LEDs are usually built on an n-type substrate, with an electrode attached to the ptype layer deposited on its surface. P-type substrates, while less common, occur as

well. Many commercial LEDs, especially GaN/InGaN, also use sapphire substrate.

Most materials used for LED production have very high refractive indices. This

means that much light will be reflected back into the material at the material/air

surface interface. Thus, light extraction in LEDs is an important aspect of LED

production, subject to much research.

Advantages

Efficiency: LEDs emit more light per watt than incandescent light bulbs. Their

efficiency is not affected by shape and size, unlike fluorescent light bulbs or tubes.

Color: LEDs can emit light of an intended color without using any color filters as

traditional lighting methods need. This is more efficient and can lower initial costs.

Size: LEDs can be very small (smaller than 2 mm and are easily populated onto

printed circuit boards.

On/Off time: LEDs light up very quickly. A typical red indicator LED will

achieve full brightness in under a microsecond. LEDs used in communications

devices can have even faster response times.

Cycling: LEDs are ideal for uses subject to frequent on-off cycling, unlike

fluorescent lamps that fail faster when cycled often, or HID lamps that require a

long time before restarting.

Dimming: LEDs can very easily be dimmed either by pulse-width modulation or

lowering the forward current.

Cool light: In contrast to most light sources, LEDs radiate very little heat in the

form of IR that can cause damage to sensitive objects or fabrics. Wasted energy is

dispersed as heat through the base of the LED.

Slow failure: LEDs mostly fail by dimming over time, rather than the abrupt

failure of incandescent bulbs.

Lifetime: LEDs can have a relatively long useful life. One report estimates 35,000

to 50,000 hours of useful life, though time to complete failure may be longer.

Fluorescent tubes typically are rated at about 10,000 to 15,000 hours, depending

partly on the conditions of use, and incandescent light bulbs at 1,000–2,000 hours.

Shock resistance: LEDs, being solid state components, are difficult to damage

with external shock, unlike fluorescent and incandescent bulbs which are fragile.

Focus: The solid package of the LED can be designed to focus its light.

Incandescent and fluorescent sources often require an external reflector to collect

light and direct it in a usable manner.

Disadvantages

High initial price: LEDs are currently more expensive, price per lumen, on an

initial capital cost basis, than most conventional lighting technologies. The

additional expense partially stems from the relatively low lumen output and the

drive circuitry and power supplies needed.

Temperature dependence: LED performance largely depends on the ambient

temperature of the operating environment. Over-driving an LED in high ambient

temperatures may result in overheating the LED package, eventually leading to

device failure. Adequate heat sinking is needed to maintain long life. This is

especially important in automotive, medical, and military uses where devices must

operate over a wide range of temperatures, and need low failure rates.

Voltage sensitivity: LEDs must be supplied with the voltage above the threshold

and a current below the rating. This can involve series resistors or currentregulated power supplies.

Light quality: Most cool-white LEDs have spectra that differ significantly from a

black body radiator like the sun or an incandescent light. The spike at 460 nm and

dip at 500 nm can cause the color of objects to be perceived differently under coolwhite LED illumination than sunlight or incandescent sources, due to

metamerism,[90] red surfaces being rendered particularly badly by typical

phosphor based cool-white LEDs. However, the color rendering properties of

common fluorescent lamps are often inferior to what is now available in state-ofart white LEDs.

Area light source: LEDs do not approximate a “point source” of light, but rather a

lambertian distribution. So LEDs are difficult to apply to uses needing a spherical

light field. LEDs cannot provide divergence below a few degrees. In contrast,

lasers can emit beams with divergences of 0.2 degrees or less.

Blue hazard: There is a concern that blue LEDs and cool-white LEDs are now

capable of exceeding safe limits of the so-called blue-light hazard as defined in eye

safety specifications such as ANSI/IESNA RP-27.1–05: Recommended Practice

for Photo biological Safety for Lamp and Lamp Systems.

Electrical Polarity: Unlike incandescent light bulbs, which illuminate regardless

of the electrical polarity, LEDs will only light with correct electrical polarity.

Blue pollution: Because cool-white LEDs (i.e., LEDs with high color temperature)

emit proportionally more blue light than conventional outdoor light sources such as

high-pressure sodium vapor lamps, the strong wavelength dependence of Rayleigh

scattering means that cool-white LEDs can cause more light pollution than other

light sources. The International Dark-Sky Association discourages using white

light sources with correlated color temperature above 3,000 K.

Droop: The efficiency of LEDs tends to decrease as one increase current.

Printed Circuit Board

A printed circuit board, or PCB, is used to mechanically support and

electrically connect electronic components using conductive pathways, tracks or

signal traces etched from copper sheets laminated onto a non-conductive substrate.

It is also referred to as printed wiring board (PWB) or etched wiring board. A PCB

populated with electronic components is a printed circuit assembly (PCA), also

known as a printed circuit board assembly (PCBA). Printed circuit boards are used

in virtually all but the simplest commercially-produced electronic devices.

PCBs are inexpensive, and can be highly reliable. They require much more layout

effort and higher initial cost than either wire wrap or point-to-point construction,

but are much cheaper and faster for high-volume production; the production and

soldering of PCBs can be done by totally automated equipment. Much of the

electronics industry's PCB design, assembly, and quality control needs are set by

standards that are published by the IPC organization.

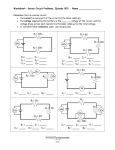

CIRCUIT DIAGRAM

PROTOTYPE

Construction

The Prototype of the circuit was constructed on a general purpose PCB.

Components are connected as shown in the connection diagram and the Piezo

element is connected to the circuit using a thin insulated wire. Gluing the flat side

of the piezo element on a 30*30 cm aluminium sheet will increase its sensitivity.

Fix the Sheet with the piezo sensor to the site where protection is needed. The

remaining circuit can be fixed at a suitable place. If only alarm generator is needed,

omit Relay driver section.

Working

The entire circuit has two sections- the sensor and the power supply section.

(1)Sensor Side circuit

The circuit diagram shows the fire sensor circuit. The front end of the

circuit has a sensitive signal amplifier built around IC1 (CA 3130). It gives a high

output when temperature near the Piezo element increases. IC CA3130 is a CMOS

operational amplifier with gate protected p-channel MOSFETs in the inputs. It has

high speed of performance and low input current requirements. There are two

inputs – the non inverting input (pin 3) connected to the Piezo element through

diode D7 (OA71) that carries the voltage signal from the Piezo element through

diode D7 (OA71) that carries the voltage signal from the Piezo element through

diode D7 (OA71) that carries the voltage signal from the Piezo element and the

inverting input (pin 2) that gets a preset voltage through VR1.By adjustingVR1,it

is easy to set the reference voltage level at pin 2. In normal condition, IC1 gives a

low output and the remaining circuitry is in a standby state. Capacitor C2 keeps the

non-inverting input of IC1 stable, so that even a slight change in voltage level in

the inputs can change the output to high. Normally, IC1 gives a low output,

keeping transistor T1 non-conducting. Resetting pin 12 of IC2 (CD4060 connected

to the collector of transistorT1 gets a high voltage through R5 andIC2 remains

disable. When the Piezo element gets heat from fire, asymmetry in its crystals

causes a potential change, enabling capacitor C2 to discharge. It momentarily

changes the voltage level at pin 3 of IC1 and its output swings high. Transistor T1

conducts taking the reset pin 12 of IC2 to ground. IC2is now enabled and starts

oscillating. With the shown values of the oscillating components C3 (0.22μ) and

R6(1M), the first output (Q3) turns high after a few seconds and a red LED2starts

flashing. If heat near the Piezo persists, Q7 (pin 14) output of IC2 becomes high

after one minute, and the alarm starts beeping. If heat continues, Q9 (pin 15) turns

high after four minutes and turns on the relay driver transistor T2. At the same

time, diodeD8 conducts and IC2 stops oscillating and toggles.

Conclusion

This Pyroelectric Fire Alarm is designed to Sense a rise in room temperature due to

heat. Unlike Thermister based Fire sensors, here an ordinary Piezo element of

Buzzer is used as the Fire sensor. The Lead Titanate Zirconate crystals in the Piezo

element have the property to deform and generate an electric potential when

heated. This property is exploited in the circuit to make an ultra sensitive Fire

Alarm. Unlike Thermister based Fire sensors, this circuit can detect a 10 degree

rise in temperature and gives a warning alarm even before the fire breaks. If the

temperature continues due to fire, it automatically operates a relay which can be

used to switch on a Water sprayer or Solenoid pump to spray water or fire ceasing

foam

.

REFERENCES

Electronic principles- Albert Paul Malvino

Principles of electronics- V.K.Mehta

Electronic fundamentals and applications - Millman & Halkias

WEBSITES

www.electronicsforu.com

www.electroschematics.com

www.dmohankumar.wordpress.com

www.electroskan.wordpresscom

www.alldatasheets.com