* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download B. The Traditional Music of Karawitan

Musical syntax wikipedia , lookup

Music technology (electronic and digital) wikipedia , lookup

Appropriation (music) wikipedia , lookup

Music-related memory wikipedia , lookup

Sangita Ratnakara wikipedia , lookup

Cognitive neuroscience of music wikipedia , lookup

Classical music wikipedia , lookup

Musical instrument wikipedia , lookup

Popular music wikipedia , lookup

Museo internazionale e biblioteca della musica wikipedia , lookup

World music wikipedia , lookup

Orchestration wikipedia , lookup

Music theory wikipedia , lookup

Music technology wikipedia , lookup

Musical film wikipedia , lookup

Music technology (mechanical) wikipedia , lookup

Music psychology wikipedia , lookup

Musical instrument classification wikipedia , lookup

History of music in the biblical period wikipedia , lookup

Experimental musical instrument wikipedia , lookup

Musical composition wikipedia , lookup

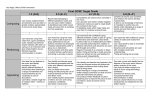

MUSICAL GENRES IN MUSIC OF KARAWITAN By Bambang Sunarto Abstract This article elaborates on categories of artistic on musical composition of karawitan music, characterized by particular styles. This writing is intended to describe or depict scenes of musical form and their framework or pragmatic context in everyday life in Javanese music culture. This elaboration was done by indentifying and taking apart the components of of any term and musical concept as manifestation of the cultural statements that exist in everyday life. The outcome of this explanation is a new conception and perception of artistic categories related to the medium, musical construction, and pragmatic reality. In new creations of karawitan music, one can distinguish a new karawitan with classic/traditional nuances ,another with popular nuances, with reinterpretation, and with an experimental or explorative nature. This writing seeks to characterize a generic idea generalized from particular instances of karawitan music. Keywords: musical genre, aesthetic category, characteristic classification, musical treatment A. Introduction Both the conception and form of the term “karawitan”, are cultural realities that have grown in the area of Javanese culture. The image held by Indonesian people outside Java in general is that karawitan is equivalent to gamelan music1. The layman’s perspective of karawitan is also understood to be music of gamelan, even by Javanese people. The word “gamelan” is a term used to indicate a group of instruments typically from Java and/or Bali, featuring a variety of instruments such as metallophones, xylophones, drums and gongs as well as bamboo flutes, rubbed and plucked strings in a particular assembly to express karawitan music. Karawitan music can be expressed without the medium of gamelan. So, the understanding of karawitan as music of gamelan is not entirely accepted, because Javanese karawitan is in fact often expressed in the form of music that does not use gamelan instruments. The expression of karawitan music without the medium of gamelan has a nature of characters, concepts and ways of expression which is synonymous with karawitan music expressed by using gamelan medium. During its development, as stated by Supanggah2, the term karawitan is now used to refer to a variety of various musical types that have the nature, character, concept, way of work, and or rules that is similar to the music of karawitan. This understanding grows through the consideration of increasing urbanization as an important phenomenon since the 1970s in Indonesia, especially in Java,. This happens because urbanization has intense effects not only on the ecology of a region and on its economy, but also but also on the conditions of cultural arts in some communities. Urbanization is essentially the increase over time in the population of cities in relation to the region's rural population. The most striking immediate change accompanying urbanization is the rapid change in the prevailing character of local livelihoods through agriculture or more traditional local services and small-scale industry. It gives way to modern industry and urban and related commerce, with the city drawing on the resources of an ever-widening area for its own 1 Supanggah, R. 2002. Bothekan Karawitan I. Jakarta: Ford Foundation & Masyarakat Seni Pertunjukan Indonesia. p. 5. 2 Supanggah, R. 2002. . Bothekan Karawitan I. p. 5. sustenance and goods to be traded or processed into manufactured goods. These factors all have significant impact on the life of karawitan music. The music of karawitan in the context of urbanization is understood to be music with musical construction and typicality, manner and genuine form of cultural expression of the ethnic music in Indonesia. Therefore karawitan embodies the meaning of descriptive terms with very broad domains. The ranges of possible musical entities are classified into (1) culture areas, (2) personal characters, (3) a character of groups, and (4) a musical genre. Classification of the karawitan based on the region of musical culture points to the musical style that is determined by the music dialectics with talent, character, and aesthetic tendencies that grow and develop in a particular area of musical culture. This classification essentially points to the style of typicalities marked by musical medium, manner and form of expression applied and abided by the artists and practitioners in a particular area of musical cultures, such as the musical styles of Sundanese, Minangkabau, Bali, Banyumas, Yogyakarta, Surakarta, Jawatimuran, Madura, Cirebonan, Semarangan, Sragenan, and so on. The classification based on personal character refer to the types of karawitan that are determined by a strong musical talent, character, and aesthetic tendencies that grow and develop in an individual artist. Classification thereby generates the musical aesthetic style of Nartosabda, Tjakrawasita, Martopangrawit, Rasito, Mang Koko, Gede Manik, and so on. Classification based on the musical character of the group points to musicality that is determined by the strong tendency of aesthetic that grows and develops in a particular musical community. This classification results in understanding a musical entity with a particular style of musical styles such as RRI Surakarta, RRI Ngayogjakarta, Pakualaman Pura, Pura Mangkunegaran, the Palace of Surakarta, Surakarta ASKI musical styles, and so on. The classification of karawitan music based on musical genre is essentially pointing to musical style or aesthetic flow with the trend and content of the certain conceptual fields. This classification refers to types of music that are determined by musical ideas, and contents color its musical form and configurations. Musical ideas relate to medium, vocabulary, musical treatment, and inclination of its message. The existential reality of the music of karawitan can be grouped into two major genres, namely (1) traditional music of karawitan, and (2) new musical work of karawitan. The new musical works of karawitan can be subdivided into (2.a) new traditional karawitan music, and (2.b) contemporary karawitan music. New musical works in karawitan usually consist of three categories, namely (2.a.1) new musical karawitan on classic-traditional, (2.a.2) popular karawitan music, and (2.a.3) a type of karawitan music called gagrag anyar. Karawitan as a musical genre may be mapped as follows. New Musical Karawitan on Classic-Traditional Traditional Music of Karawitan New Traditional Music of Karawitan MUSIC OF KARAWITAN New Musical Work of Karawitan Popular Music of Karawitan Karawitan Music of Gagrag Anyar Contemporary Karawitan B. The Traditional Music of Karawitan The meaning of the term “traditional” is essentially something related to the manner, method, or typical style as a legacy of culture that are still alive in the present day. It cannot be separated from the mindset, behaviors, actions and attitudes to life as a cultural habit. The meaning of “traditional” is often understood as “classic”, so the term “traditional karawitan music” is normally understood as classical karawitan music. These two terms (traditional and classic) are often used with very wide and overlapping connotations and denotations. The sense of “classic”, which is also meant as traditional, here is understood as related to the principles or standards that are followed, appreciated, and respected continuously and inhereted from generation to generation in specific artistic fields. The principle or the standard in the karawitan music is embodied in the arrangement and work of a musical system with specific characteristics that are transmitted by means of oral tradition, the creator of which is often anonymous. That is why a classic conception in music of karawitan here is also stated as traditional, because neither musical conceptions can be separated. The body of traditional karawitan music is musical composition the form, structure, and treatment of which refer to the standard of conventional form, structure, and musical treatment of the musical culture of karawitan music. Gendhing as the composition of traditional karawitan music constitutes anonymous creation in a cultural music legacy. Other nature of the gendhing are close and stuck to musicians or pengrawit, and its musical performance is completely dominated by the pengrawit. The traditional music of karawitan is marked by existing repertoire, a wealth of gendhings that can be classified into (1) gendhing ageng and (2) gendhing alit. Gendhing ageng is understood to be conventional music composition, both the treatment and appreciation of which need deep and adequate provisions and comprehensions. Both its structure and treatment are relatively complicated, and a whole musical composition comprises no less than four sections. Each section has different form and structure. Gendhing alit is also conventional music composition, but neither its treatment nor its appreciation require deep and adequate provisions and comprehensions. Both its structure and treatment is relatively simple, uncomplicated, easy to imitate, so it is easy to learn. It is possible that a single musical composition comprises only one part of the form. 1. Medium Traditional karawitan music as an expressive tool is performed using the media of voice or conventional gamelan, and/or the combination of voice and conventional gamelan. The conventional gamelan is a group instrument, and its empirical form is music cultural heritage. It is not result of new engineering. Existent material of conventional gamelan has existed far ahead of new instruments, a result of new musical instrument engineering that its material existent presents contemporaneous with the author of this article. The involvement of the human voice in the music of karawitan is not a must. Vocal parts in karawitan music differ from vocal parts in other music tradition, especially musical tradition that places the voice as the “main” entity, since without its presence it is incomplete, and presentation of music cannot be implemented. If in a music composition there is a musical part that usually presented by vocal voice, and there is no figure capable of presenting the vocal part, that part should be presented by the sound of other instruments. The human voice in karawitan music shares its position with other sound entities presented by the treatment through gamelan instruments. 2. Various Kinds of Gamelan The conventional instruments of gamelan music are ensembles that exist in the island of Java, Madura, Bali, Kalimantan (Borneo) and Lombok in various kinds of sizes, shapes of ensembles, and pragmatic contexts. In Java especially two musical cultures have developed, namely (1) Javanese music culture scattered throughout Central Java and East Java, and (2) Sundanese musical culture scattered throughout West Java. People sometimes mention gamelan using the term “gong”. The term “gong” is considered synonymous with gamelan in Bali and Lombok today, as well was the case in Java from the eighteenth century up to mid-nineteenth century. Conventional gamelan instruments are formed and arranged in ensembles in a systemic manner, through the inheritance of a long history. The following are examples of some conventional gamelan, from Javan, Sunda, Madura, Borneo, and Bali. Picture 1: Conventional Javanese Gamelan Ensemble Named Gamelan Ageng Picture 2: Conventional Sundanese (the West Java) Gamelan Ensemble Named Gamelan Degung Collection of the University College London, United Kingdom Picture 3: Conventional Maduranese Gamelan Ensemble Named Gamelan Klenangan Picture 4: Conventional Gamelan from Borneo Named Gamelan Banjar Rakyatan Collection of the Lambungmangkurat Museum Picture 5: Conventional Balinese Gamelan Named Gamelan Gong Kebyar Haryono describes that gamelan has been mentioned in some inscription, literary texts, and temple reliefs from the eighth to the tenth century3. Haryono has mentioned some inscriptions, those of Wukajana, Poh, Kuburan Candi, Kembang Arum, Gandasuli II, Kuti, and Kwak I. Haryono also points to some literary text that mention instrument of gamelan, namely Bharatayuddha, Bhomakavya, Smaradahana, Nagarakrtagama, Kidung Ranggalawe, Kidung Sundha, Kidung Harsawijaya, Kidung Pamancangah, Sri Tanjung and Panji Stories. The reliefs mentioned above are found in the temple of Kedaton, Penataran, Sukuh, Borobudur, Loro Jonggrang, Pamandaian Jalatunda, Jago, Ngrimbi, Kedaton, and Tegalwangi. Ferdinandus has also described traces of the history of gamelan that is scattered in various inscriptions, ancient literary texts, and temple reliefs on IX-XV century4. Besides mentioning mentions inscriptions, ancient literary texts, and temple reliefs that have been mentioned by Haryono, Ferdinandus also mentions some temples such as Borobudur, Prambanan, Jalatunda, Jago, and Jawi. Unfortunately, there is no historian who describes the process of the formation of the gamelan ensemble so that it becomes complete as found in the present day. Soetrisno has also discussed the whole things that are presented by Haryono and Ferdinandus5. All of them confirm that formation of the gamelan ensemble occurs gradually 3 Haryono, T. 2001. Logam dan Peradaban Manusia. Yogyakarta: Philosophy Press. p. 07-114; & Haryono, T. 2008. Seni Pertunjukan dan Seni Rupa dalam Perspektif Arkeologi Seni. ISI Press Solo. Surakarta. p. 138-169. 4 Ferdinandus, J.P.E. 2001. Alat Musik Jawa Kuno. Kajian Bentuk dan Fungsi Ansamble Abad IX-XV Masehi. Yayasan Mahardika. Yogyakarta. 5 Soetrisno, R. 1976. Sejarah Karawitan. Akademi Seni Karawitan Indonesia. Surakarta. so as to achieve the peak of perfection. That perfection is more real since the reign of Pakubuwono X (1893-1939) in Surakarta. The perfection appears in various artifacts of gamelan made in that time. The perfection in various contexts and for various purposes is developed further by contemporary artists in the post independence era. Javanese karawitan has several types of ensembles; a group of supporting musicians and instruments are bound into one unified system to obtain a full complement of harmonizing expression, including the following ensembles: (1) gamelan ageng, (2) gamelan gadhon, (3) gamelan cokekan, (4) gamelan kodhok ngorèk, (5) gamelan monggang, (6) gamelan corabalen, and (7) gamelan sêkatèn. Supanggah has described the form and function of these set of ensembles, with the exception of gamelan cokekan and gamelan gadhon6. There is a set of gamelan ensemble the instruments of which are formed of wilahan gambang or xylophones, and made of bamboo. This ensemble generally develops in the periphery of Javanese culture, Banyumas. This bamboo gamelan is called gamelan calung. The role and function of this gamelan ensemble imitates the nature instruments of gamelan agêng. Meanwhile, gamelan agêng is mostly dominated by type instrument of wilahan and pêncon type instruments. Yasa states that in Bali there are about 26 types of gamelan ensemble that have the treatment, shape of gendhing, timbre, function of instrument, character and different repertoire of gendhing7. Sukerta recorded 31 type set or “barungan” of gamelan, which include barungan angklung don nem, angklung kembang kirang, angklung kléntangan, bebatelan, bumbung gebyog, caruk gambang, gebug ende, genggong, gong beri, gong duwe, gong gede, kebyar gong, gong luang, gong pareret, gong suling, jegog, kendhang barung, parwa, pegambuhan, pejangeran, pejogedan, geguntangan, rindik gegandrungan, saron, selonding, semar pagulingan saih lima, semar pagulingan saih pitu, semarandana, tektekan/okokan, and trompong beruk8. Most gamelan in Bali and in Java contain percussive instruments, comprising wilahan and pencon instruments. There are several complementary instruments, as in Java, including (1) cymbals instrument or kecer that in Bali is called ceng-ceng, (2) kendhang instruments that usually consist of pairs, called kendhang lanang and kendhang wadon respectively, (3) suling (flute) that have a variety of shapes and sizes, and (4) rebab (fiddle). The type of zither known as siter and celempung in Java is not found in Balinese karawitan music. However, a new musical genre called gènjèk has recently been developed in Bali . This music is a subgenre of Cakepung, using plucked instrument like zither9. In Java there is gamelan calung, the entirety of whose instruments take the in shape of wilahan or xylophone types. This may also be found in in Bali, as there are numerous gamelan ensemble made of bamboo such as (1) gamelan jegog, (2) gamelan joget bumbung, (3) gamelan rindik, (4) gamelan gambang, and (5) gamelan gandrung10. These instruments musically imitate the form, role, functions, intern and extern relations of gamelan ageng in Bali, such as (1) gamelan gong kebyar and (2) gamelan semar pagulingan. Various types of gamelan are also found in Sunda, in cultural province of West Java. The existence of gamelan in Sunda can be seen in various genres of art such as (1) kethuk tilu, 6 Supanggah, R. 2002. p. 32-37. Yasa, I.K. 1991. Gendhing-gendhing Dalam Upacara Memungkah di Pura Dadia Agung Pasek Bendesa Tonja. Laporan Penelitian. Sekolah Tinggi Seni Indonesia (STSI) Surakarta. 8 Sukerta, P.M. 2004. Perubahan dan Keberlanjutan dalam Tradisi Gong Kebyar: Studi tentang Gong Kebyar Buleleng. Disertasi Doktor. Denpasar: Universitas Udayana. 9 I Nyoman Sukerna, interview 5 Juli 2008. 10 I Nyoman Sukerna, interview 5 Juli 2008. 7 (2) jaipongan, (3) degung, (4) bajidoran, and other arts11. Rasita Satriana explained that in Sunda there are numerous set of gamelan such as (1) gamelan renteng, (2) gamelan ajeng, (3) gamelan saléndro-pelog that is called gamelan prawa-prada in Cirebon, (4) gamelan degung, (5) kecapi ensemble, (6) tarawangsa ensemble, (7) calung ensemble, (8) calung ensemble, (9) angklung ensemble, and (10) gamelan pencak silat (martial drums)12. New gamelan has recently been born in Sunda called gamelan selap, with modification of its scale system (Sopandi, 2006). Meanwhile, Natapradja divides gamelan in Sundanese karawitan music into two categories: (1) gamelan utama [main gamelan], and (2) gamelan madya [middle gamelan]. Gamelan utama consists of gamelan renteng, gamelan degung, gamelan pamirig kethuk tilu, and gamelan saléndro-pélog. Gamelan madya consists of gamelan ajeng, gamelan lilingong, gamelan munggang, gamelan cokek, gamelan gambang kromong, and gamelan kemodong13. Physical form of Sundanese gamelan is not much different with gamelan in Java and Bali. Most of its instruments are percussive, comprising a group of instruments shaped like wilahan and pencon. Typical added instruments in Sundanese karawitan music are kendhang (drums), various types of suling (flutes), and plucked strings instruments called kecapi, and another bowed string instrument called rebab (fiddle). In Sundanese karawitan music there is also gamelan angklung and calung as found in Java that are made of bamboo. Gamelan calung in Sundanese culture and in Java have fundamental differences in their organological structure. C. The Types of Instruments in the Gamelan A gamelan is a set of instruments that form a distinct entity, as they are built and tuned to stay together; instruments from different gamelan are not generally interchangeable. The gamelan in Central Java feature a variety of instruments, most of which are percussive. They can be categorized into the following groups: (1) pencon instruments (2) wilahan instruments (3) drums, (4) bamboo flutes, and (5) bowed and plucked strings. 1. Pencon The pencon group consists of circular, metal percussion instruments, each with an overturned rim, that resemble plates They are struck in the centre with a soft covered beater, to produce a sound of either definite or indefinite pitch. Pencon instruments have deep rims and are bossed (knobbed) in the centre. There are two broad categories of pencon: pencon gantung and pencon renteng. Pencon gantung are those that are usually called gongs. They are hung and come in various sizes: the is the gong ageng, three type of gong suwukan and ten types of kempul. Pencon renteng consist of a group of small gongs that are arranged in a row. The pencon gantung consists of (1) the gong ageng, (2) the gong suwukan, and (3) the kempul. The gong ageng (which means ‘large gong’, and is also called gong gedhe) is a musical instrument that has a fixed, focused pitch. It is circular, and has a conical, tapering base whose diameter smaller than the upper face. It also has a protruding polished boss which it is struck by a padded mallet. Gongs whose diameters are as large as 135 centimetres (54 inches) were made in the past, but gongs with diameters of about 80 centimetres (32 inches) are more common today, especially because such gongs better suit the budget of 11 Sopandi, C. 2006. Gamelan Selap: Kajian Inovasi Pada Karawitan Wayang Golek Purwa. Tesis S-2. Program Studi Pengkajian Seni. Institut Seni Indonesia (ISI) Surakarta. p. 1. 12 Rasita Satriana, interview 6 Juli 2008. 13 Natapradja, I. 2003. Sekar Gendhing. Bandung: PT. Karya Cipta Lestari. p. 97-129. educational institutions. There is at least one large gong in each gamelan, but it is common to have two. The gong suwukan is a smaller gong that is used to mark smaller phrases. It is generally higher pitched, and is pitched differently for pélog and sléndro. A gamelan will frequently have several gong suwukan, for different ending notes and pathet (musical mode in karawitan). The most common note or tone for pathet sanga and lima is 1, but for pélog pathet nem and barang, and sléndro pathet nem and manyura, it is 2. A 1 can be usually be played for balungan ending in 1 or 5, and a 2 can be played for 2 or 6. A few gamelan have a gong suwukan 3 as well. The kempul is a type of hanging gong that is often placed with the gong suwukan and gong ageng. All kempul hang on a single rack at the back of the gamelan, and these instruments are often played by the same player with the same mallets. There are usually several kempul for each pélog and sléndro; however, there are frequently some notes for which otherly pitched kempul must be played (usually at a related interval, like a fifth). The appropriate kempul depends on the balungan, the pathet (mode), and other considerations. The kempul in Javanese, Balinese and Sundanese gamelan has a colotomic function, similar to the kenong and kethuk-kempyang. Below is a picture of pencong gantung (hanging pencon), which consists of gong ageng (or geng gedhe), gong suwukan, and kempul which are attached to single rack. Picture 6: A group of gong (pencon gantung) in a Javanese gamelan ensemble Consist of a gong ageng, three type of gong suwukan dan ten type of kempul Pencon renteng come in several basic types, such as the bonang, the kenong, and the kethuk kempyang. The bonang consists of a collection of small gongs (sometimes called "kettles" or "pots") placed horizontally onto strings mounted to a wooden frame (rancak), either one or two rows wide. All of the kettles have a central boss, but the lower-pitched ones have a flattened head, while the higher ones have an arched head. Each gong is tuned to a specific pitch in the appropriate scale; thus there are different bonang for pelog and slendro. In Central Javanese gamelan there are three types of bonang used. Those are the bonang penerus, the bonang barung, and the bonang penembung. The bonang panerus is the highest pitched, and thus uses the smallest kettles. It generally covers two octaves, which roughly corresponds to the range as saron and peking instruments combined. It plays the fastest rhythms of the bonang, either interlocking with the bonang barung or playing at twice its speed. The bonang barung is pitched one octave below the bonang panerus, and also generally covers two octaves with correspond to the range of the demung and saron combined. This is one of the most important instruments in the ensemble, as it gives many cues to the other players in the gamelan. The bonang panembung is the lowerst pitched. Its range covers approximately the same range as the slenthem and demung instruments combined. It is reserved for the most austere repertoire, and typically plays a paraphrase of the balungan. The parts played by the bonang barung and bonang panerus are more complex than many instruments in the gamelan; thus, it is generally considered an elaborating instrument. In essence they play melodies that are based on the balungan (or musical skeleton), though these generally modified in a simple way. However, they can also play more complex patterns, which are obtained by combining barung and panerus patterns; such alternations may be interlocking parts, usually called imbal, or they may be the interpolation of florid melodic patterns that usually called sekaran. Below is a picture of pencong renteng, a group of small gongs are arranged in a row, namely the of bonang barung and bonang penerus in pairs, for both in slendro and pelog tuning systems. Picture 7: A group of bonang in a Javanese gamelan ensemble Consist of bonang barung in slendro and pelog as well as bonang penerus in slendro and pelog 2. Wilahan The instruments of the wilahan can be divided into three types, namely (2-a) the wilahan gambang or xylophones, (2-b) the wilahan gender, and (2-c) the wilahan balungan or metallophones. The wilahan gambang or xylophone instruments are percussion instruments which consist of a set of graduated, tuned wooden bars supported at nodal (nonvibrating) points and struck with padded mallets. The bars of the instrument are made of a dense wood, generally teak. It also found in ironwood (kayu besi). The bars are mounted in a deep wooden case that serves as a resonator. Instruments typically have 17-21 keys that are easily removed, and are kept in place by a hole and nail. A full gamelan generally has two sets, one pelog gambang and one slendro gambang. Picture 8: A a gambang instrumen in a Javanese gamelan ensemble Source http://orgs.usd.edu/nmm/Gamelan/9883/Gambang9883.html A pair of long thin mallets (tabuh), made of flexible water buffalo horn tipped with felt, are used to play the instrument. Gambangs are generally played in parallel octaves (gembyang). Occasionally, other styles of playing are employed such as playing kempyung which are played by striking two notes separated by two keys. Unlike most other gamelan instruments, no dampening is required, as the wood does not ring like the metal keys of other instruments. In Javanese gamelan, the gambang is an elaborating instrument. The wilahan gender is a kind of metallophone instrument arranged in row with with hanging resonators. It consists of 14 tuned metal bars, each suspended over a tuned resonator of bamboo or metal, which are then struck with a mallet made of a padded, wooden disk. Each key is a note of a different pitch, often extending a little more than two octaves. There are five notes per octave, so in the seven-note pélog scale, some pitches are left out according to the pathet. Most gamelans include three gender, one for slendro, one for pelog pathet nem and lima, and one for pelog pathet barang. Picture 9: A gambang instrument in a Javanese gamelan ensemble There are essentially there are two genders which are used, the gender barung and the gender panerus. The main difference between them is that gender panerus is octave higher than the gender barung. The gender panerus plays a pattern that consists of single melodic line , following a pattern similar to the siter. The gender barung plays a slower, but more complex melodic pattern characterized by more separate right and left hand melodic lines that come together in kempyung (approximately a fifth) and gembyang (octave) intervals. The melodies of the two hands sometimes move in parallel motion, but often play contrapuntally. Since playing gender barung requires two mallets, the dampening technique, which important to most gamelan instruments, becomes more challenging: the previously hit notes must be dampened by the same hand immediately after the new ones are hit. This is sometimes possible by playing with the mallet at an angle (to dampen one key and play the other), but may require a small pause. The wilahan balungan or metallophones instruments are percussion instrument consisting of a series of struck metal bars. There are three instruments that can be classified in wilahan balungan, as they come in a number of different sizes. From largest to smallest, they are the demung, saron, and saron penerus. Each one of those is pitched an octave above the previous. It provides the core melody (balungan or skeleton) in the gamelan orchestra. Below is a picture of wilahan balungan instruments, including the demung, saron, and saron penerus. Picture 10: The Balungan instrument in Javanese gamelan in the form of wilahan balungan 3. Kendhang Another type of instrument in gamelan is the kendhang. In Malay, is called gendang, while in Tausug/Bajau Maranao it is known as gandang. It is a two-headed drum, thus technimcally classified as a membranophone among the percussion group of musical instruments. In Java, especially in Central Javanese gamelan (both in Surakarta and Yogyakarta) there are four sizes of kendhang. Firstly, there is kendhang ageng or kendhang gedhe, which can also be named kendhang gendhing. It is the largest kendhang, and usually has the deepest tone. It is played by itself in the kendhang satunggal style, which is used for the most solemn or majestic pieces or parts of pieces. Secondly, there is the kendhang ketipung. It is the smallest kendhang, used with the kendhang ageng in kendhang kalih style, which is used in faster tempos and less solemn pieces. Picture 11: The Kendhang Ageng and Kendhang Ketipung in Javanese gamelan Thirdly, there is the kendhang ciblon. It is a medium-sized drum that used for the most complex or lively rhythms. It is typically used for livelier sections within a piece. The word ciblon derives from a Javanese type of water-play. The term ciblon or water-play refers to the way in which people smack the water with different hand shapes to give different sounds and complex rhythms. Naming this kendhang technique ciblon indicates that it is meant to imitate water-play, and thus is more difficult to learn than the other kendhang styles. Picture 11: The Kendhang Batangan or Kendhang Wayang in Javanese gamelan Finally, there is the kendhang batangan or kendhang wayang. It is also medium-sized, and it was traditionally used to accompany wayang performances, although now other drums can be used as well. This kendhang has the same shape as the kendhang ciblon, but it has a slightly larger size, so that the resulting sound is also slightly deeper. The technique for playing this kendhang is not much different from the kendhang ciblon, but it requires a very different vocabulary of musical expression. 4. Bamboo Flutes A suling is bamboo ring flute. It is made mainly of bamboo (schizostachyum blumei) that has kind of a long tube bamboo with a very thin surface. The head of suling, near a small hole, is circled with a thin band made of rattan or rotan to produce air vibration. a thin circle band made of rattan Picture 12: The Sulings in Javanese gamelan When playing a suling, there are two factors that affect its pitch: the fingering position, and the speed of the airflow from the player’s mouth. The fingering position changes the wavelength of the sound resonance inside the suling's body. Depending on the distance of the nearest hole to the suling's head, different notes can be produced. The airflow speed also can modify the tone's frequency. A note with twice the frequency of a given fingering can be produced by blowing the air into suling's head's hole with twice speed. Picture 13: The Slendro Suling in Javanese gamelan with four hole 5. Bowed and Plucked Strings In Indonesia, there are two kind string instruments. The bowed or swiped string instrument is known as a rebab, and the plucked string instruments are known as the siter and the celempung. The following is a picture of the rebab. Picture 14: The Rebab in Javanese gamelan It can be tuned in Slendro or Pelog As said by Lindsay (year or footnote?), the rebab is an essential elaborating instrument, ornamenting the basic melody or balungan. It is a two-stringed bowed lute consisting of a wooden body, that was traditionally made out of a single coconut shell, but this is rare now. The body is covered with very fine stretched skin. Two brass strings are tuned to a kempyung (a fifth) apart and a bow of horse hair is loosely tied (unlike modern Western stringed instruments); the proper tension is controlled by the players bowing hand, which contributing to the difficult technique of playing rebab. There are typically two rebabs per ensemble, one for pelog scaling system and one for slendro, thus they never played together14. The plucked string instruments of the gamelan ensemble are the siter and celempung. The siter is the small stringed instrument in a gamelan, while celempung is a bigger than siter. The following are pictures of the siter and celempung. Picture 15: The Siter in Javanese gamelan It can be tuned in Slendro or Pelog 14 Lindsay, J. 1992. Javanese Gamelan: Traditional Orchestra of Indonesia. Singapore ; New York : Oxford University Press. p. 30-31. 2 1 Picture 16: The Celempung in Javanese gamelan It can be tuned in Slendro or Pelog, 1. Viewed from the front, 2. Viewed from the side The siter and celempung each have between 11 and 13 pairs of strings, strung on each side between a box resonator. Typically, the strings on one side are tuned to pélog and those on the other to slendro. The siter is generally about a foot long and fits in a box (onto which it is set upon while played), while the celempung is about three feet long and sits on four legs, and is tuned one octave below the siter. They are used as elaborating instruments that play melodic patterns known in karawitan music as cengkok (patterns based on the balungan). Both the siter and the celempung play at the same speed as the gambang, which is fast. The strings of both the siter and the celempung are played with the thumbnails, while the fingers are used to dampen the previous strings when the next one is hit, as is typical with instruments in the gamelan. The fingers of both hands are used for the damping, with the right hand below the strings and the left hand above them. D. Musical Construction The most essential specification of karawitan music lies in its musical construction. The construction of karawitan music is determined by using the following elements: (1) tones, (2) scales or tuning systems, (3) musical time management, (4) a harmonic system, (5) vocabulary, and (6) relations between vocabulary and management other elements management. The term “tone” is commonly used to describe a sound that has definite pitch and vibration. In music, the term “pitch” refers to the position of a single sound in the complete range of sound. Sounds are higher or lower in pitch according to the frequency of vibration of the sound waves producing them. One of the characters of a tone is that of controlled pitch and timbre. To achieve a typical character of sound and timbre, the degree of highness or lowness of pitch in karawitan music is not based on mathematical calculations with accurately measured frequency. The measurement of tone vibration tends to take qualitative senses into consideration. The scale or tuning systems used are slendro and pelog. More detail can be seen regarding tones in this estimate arrangement below, which demonsrates that they are not as too precise as diatonic scales. Diatonic Referred to as y La u si 1 do 2 re 3 mi 4 fa 5 sol Pelog Referred to as 1 Ji 2 ro 3 lu 4 pat 5 mo 6 nem 7 pi Slendro 1 2 3 5 Referred to as Ji ro lu mo 6 nem Basically the tuning varies so widely from island to island, village to village, and even gamelan to gamelan. It is difficult to characterize in terms of intervals. One rough approximation expresses the seven pitches of Central Javanese pelog as being a subset of 9tone equal temperament. An equal temperament is a musical temperament, or a system of tuning, in which every pair of adjacent notes has an identical frequency ratio. As pitch is perceived roughly as the logarithm of frequency, this means that the perceived “distance” from every note to its nearest neighbor is the same for every note in the system. As happens in pelog, the slendro scale often varies widely. The amount of variation also varies from region to region. For example, slendro in Central Java varies much less from gamelan to gamelan than it does in Bali, where ensembles from the same village may be tuned very differently. The five pitches of the Javanese version are roughly equally spaced within the octave. As the determination of tone that does not give priority to accuracy of each frequency, it influences the nature of sound in each instrument. The shared typicality of the instrument sounds causes naturally unique and distinctive sound vibrations that are called embat. Musical time management is determined by the conception of gatra that constantly extend to be concepts of irama. In karawitan music irama is the relative width of the gatra which has certain hierarchical stages. Gatra is the basic concept of musical composition in karawitan music. A form of gatra is set of four pulses, beats or taps in a unit, as the smallest element of musical composition. Each pulse beat or tap has its own position, function and role within the hierarchy of irama15. The connotation of gatra has conceptual similarities with the concept of “bars” in Western music. It contains regularly and repeated pulses, beats or taps with constant pressurized and non-pressurized accents16. However, it must be recognized that the denoted meaning of gatra and bar are essentially different concepts. The harmonic system in karawitan music does not recognize the combination of tones that are sounded simultaneously, which is formulated rigidly through calculating frequency, so there is combination formulas based on gathering certain frequency of tones, each of which is not easy moved to the position or shape of different arrangements. Karawitan music does not give priority to the system of chords. Its concentration or emphasis is on its artistic attention to the melodic system. Vocabulary that is produced and used is a logical consequence of the use of the medium and constituent elements of musical construction. Its form is that of distinctive musical idioms or artistic style. The distinct concepts of artistic styles or musical idioms are not found in application in other music, such as the concepts of pathet, garap, balungan, cengkok, wiled, luk, gregel, seleh and sekaran. The management of the relationship between the vocabulary and musical elements used has become a regular convention of musical form. It is manifested into structures that distinguish each composition. 15 Supanggah, R. 1994. “Gatra: Inti dari Konsep Gendhing Tradisi Jawa” on Jurnal Wiled, Sekolah Tinggi Seni Indonesia (STSI) Surakarta, I/1: 13-26; Supanggah, R. 2000. “Gatra: Konsep Dasar Gendhing Tradisi Jawa”, paper to be presented in the Seminar of Karawitan, held by DUE-Like Program of STSI Surakarta; Supanggah, R. 2007. Bothekan Karawitan II: Garap. ISI Press Surakarta. Surakarta. p. 63-106; Supanggah, R. 2009. Bothekan Karawitan II: Garap. Revised Edition. Program Pascasarjana collaboration with ISI Press Surakarta. Surakarta. p. 77-129. 16 Widodo, T.S. 1997. Belajar Menyanyi dengan Not Blok 1. Yogyakarta: Penerbit Kanisius. p. 21. E. Pragmatic Reality The pragmatic realities of the classical/traditional music of karawitan appear through the context that determines their existence, related to its use in certain functions, both in the context of (1) artistic expression and (2) cultural existence. The pragmatic realities that surround classical/traditional music of karawitan are cultural contexts in a variety of traditions. These contexts can be differentiated into (1) internal and (2) external context. Internal contexts are related directly to the form of musical expression. The form of musical expression is primarily concerned with how musical expression is produced and how musical expression is expressed, so as to express the "meaning". Thus, the pragmatic reality in internal context is the production of musical expression as manifestation of interactional between musicians in the states of musical expression. The pragmatic reality in this context includes developing, managing, and utilizing musical implicature and musical references. Musical implicature is musical expression that implies something that is expressed by the music, whereas musical reference is a substance of music that has a relationship with the musical forms, which is something that is referenced by the musical form. Supanggah mentions pragmatic reality in an internal context as “perabot garap”, although he does not explicitly refer to it as pragmatic reality. Pragmatic reality or “perabot garap” includes techniques, pattern of garap, irama, laya, scale or laras, pathet, conventions, and dynamics. Therefore, the essence of implicature and musical references in karawitan is technical, pattern of garap, irama, laya, scale or laras, pathet, conventions, and dynamics that is called perabot garap by Supanggah17. The external context in the traditional music of karawitan is the use of musical expression as a tool for presenting “meaning” in the context of broad interests. The objects of such interests can be either of its own practical music of karawitan, or other than its own practical music of karawitan. The latter includes the need for (2-a) an event paying tribute to important person or atmosphere, (2-b) expressing depth of certain spirituality and religiosity, and for (2-c) helping define the aesthetic principles of other art genres. To better understand the contextual meaning of karawitan music, here with are a few pictures. Firstly, there is a picture of gamelan that is usually used to pay tribute to an event, important person or atmosphere. There are two type of gamelan that has this kind function: Gamelan Monggang and Gamelan Carabalen. Picture 17: Conventional Javanese Gamelan Ensemble Named Gamelan Monggang The archaic Gamelan Monggang of the Keraton Yogyakarta, Kanjeng Kyai Gunturlaut. 17 Supanggah, R. 2007. p. 199-247; Supanggah, R. 2009. p. 241-299. Used to welcome guests and enliven the atmosphere as sign of honorary To better understand that karawitan played with gamelan instruments is used to express the depth of a certain spirituality and religiosity, below are pictures of gamelan Sêkatèn and gamelan Gong Gede. Gamelan Sekaten is usually played to commemorate the birth day of Prophet Muhammad, SAW. The Gamelan Gong Gede is usually associated historically with public ceremonies and special occasions such as temple festivals. In short, there are only Sêkatèn in Surakarta and Yogyakarta Palace. Sêkatèn is originated from Arabic word, Syahadatain. It is from the root word “syahadah”, from the verb sahida, “he witnessed”, means “to know and believe without suspicion, as if witnessed, testimony”. Syahadah is the name of the basic Islamic creed. The syahadah is the Muslim declaration of belief in the oneness of God (tawhid) and acceptance of Muhammad as man of God, as messenger, and as prophet. The declaration in its shortest form reads in Arabic “Laa ilaaha illalLaah, Muḥammadar RasuululLaah” that in English means “There is no god but Allah, Muhammad is the messenger of Allah. Picture 18: Conventional Javanese Gamelan Ensemble Named Gamelan Sêkatèn The archaic Gamelan Sêkatèn of the Keraton Surakarta, Kanjeng Kyai Gunturmadu. This picture is ceremonial performing in frame of commemorate the birthday of prophet Muhammad, SAW. The expression of the Islamic faith – or the basic creed of Islam that verbally expressed as Laa ilaaha illalLaah, Muḥammadar RasuululLaah, there is no god but Allah, Muhammad is the messenger of Allah – needs to be done in a symbolic ceremony that is manifestation of Islamic creed. This ceremony is called Sekaten. In fact, Sekaten implies a week long Javanese traditional ceremony, including a festival, fair and night market commemorating Maulid Nabi. Th term Maulid Nabi is the birthday of prophet Muhammad, SAW. It is celebrated annually, started on 5th day through the 12th day of Maulud month in Javanese Calendar. This calendar is basically correspond to the month of Rabi' al-awwal in Islamic Calendar. The festivities usually took place in northern alun-alun (square) in Surakarta, since the Great Mosque (Masjid Agung) northern alun-alun. It is held simultaneously also celebrated in northern alun-alun of Yogyakarta. Picture below is gamelan Sekaten presented on Great Mosque (Masjid Agung) northern alun-alun in Surakarta. On the other hand, Gong Gede means “gamelan with the large gongs”. This gamelan is a form of the ceremonial gamelan music of Bali, dating from the court society of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, and as mentioned above that this gamelan is historically associated with public ceremonies and special occasions such as temple festivals. This gamelan is usually played by a temple orchestra of over forty musicians. The music written for the gong gede is sedate and graceful, and follows an andante tempo. It fluctuates in cycles, one fast, one slow, one loud, and one soft. The beat is provided by the largest gong. During colonization of Bali in the late nineteenth century, the Dutch dissolved the courts. The use of the gong gede became limited to temple music. It was later superseded in popularity by gong kebyar, a more up-tempo form of gamelan played with smaller gongs that originated in Balinese villages in the late 19th century and became widely popular in the 1920s and 1930s. The following picture is one of the gamelan Gong Gede. Most of its instruments are big like that all instruments of gamelan Sêkatèn in Java. Picture 19: Conventional Balinese Gamelan Ensemble Named Gamelan Gong Gedhe Source http://kucinggaronkblog.blogspot.com/2011_05_01_archive.html To better understand that karawitan played gamelan instruments is used to help another forms of artistic expression, especially helps define the aesthetic principles of other art genres, below is a picture that could explain (that could explain what ?). Supanggah in grouping of gendhing has called the pragmatic reality in the external context, i.e. in form of classification types of gendhing, mainly the gendhings in the musical culture of Central Java18. For example, he called the gendhing whose purpose are concerts, gendhing klenengan and gendhing dolanan. The equivalent of this pragmatic reality – or gendhing klenengan – of Central Javanese music culture, is called gendhing petegak in Bali and gendhing kliningan in Sunda. Gendhing dolanan in Bali are called gendhing rare, while in Sunda they are called sekar balareang or kaulinan urang lembur. Supanggah has mentioned gendhing pakurmatan (or admiration music) for gendhings whose purpose in mark respect for events, important people, or atmosphere19. Admiration music in Balinese music culture is connected to the cultural religious setting, and this are not simple. The choice of gendhing or gamelan orchestra that used for admiration is always associated with basic rules that must be applied in ceremony or yatnya. Yasa explains that in Bali there are five yatnya; these are (1) dewa yatnya (ceremonies dedicated to the gods), (2) rsi yatnya (ceremonies for affirming of religious duty for pemangku, wasi, and pendeta), (3) manusa yatnya (ceremonies for marking important stages and events in the life of a person), (4) pitra yatnya (ceremonies associated with death), and (5) bhuta yatnya (ceremonies held as 18 19 Supanggah. 2007. p. 135; Supanggah. 2009. p. 164. Supanggah. 2007. p. 107; Supanggah. 2009. p. 129. a manifestation of belief that in this environment there is "strength, power, and other creatures" that should be taken into account)20. Musical compositions and/or a set of gamelan orchestra that called gamelan gong gedhé are used for the dewa yatnya ceremony. These ceremonies are odalan (ceremony for temple anniversary), ngenteg linggih or mamungkah (ceremony for creating a new temple), nyepi (day of silence which is commemorated every Isakawarsa or Saka new year in Bali's calendar), saraswati (ceremony that is dedicated to Saraswati, the goddess of knowledge, music, arts, science and technology), pagerwesi (ceremony which is dedicated to the god of Siva or Sang Hyang Pramesti Guru), galungan (ceremony which is commemorated creation of the universe and its contents and the victory of dharma against adharma), kuningan (This ceremony is connected to the galungan. Galungan is a Balinese holiday that occurs every 210 days and lasts for 10 days. Kuningan is the last day of the holiday. During this holiday the Balinese gods visit the Earth and leave on Kuningan), and others. Musical compositions and/or a set of gamelan gong gedhé are used for rsi ceremony. This is ceremony in honour of the pendeta-s. Musical compositions that are expressed by gender wayang are used for the ceremony of manusa yatnya. This is ceremony to invoke the safety and commemorate events in human life, such as birth, wetonan, cutting teeth, wedding, and so on. Musical compositions that are expressed by gamelan angklung are used for pitra yatnya ceremony. This is ceremony related to the death, such as ceremony of telung dinoan (three days), bulan pitung dinoan (42 days), (3) ngaben, and (4) mukur. Musical compositions on gamelan kalaganjur are used for bhuta yatnya ceremony, such as village purification ceremony. Gamelan kalaganjur as separate ensemble is also used in a broader context, generally used for various ceremonial processions in every yatnya ceremonies. Admiration music in Balinese karawitan differs from its counterpart in Central Java. In Bali, this music is a feature required to complete ceremonial perfection of yatnya ceremony, which must equipped with a variety of sesaji, variety of offerings. Any implementation of the yatnya ceremonial must meet the panca gita, namely the (1) mantram, (2) bajra (gentha), (3) kidung (singing), (4) kulkul, (5) tabuh-tabuhan (music percussion). Karawitan is manifestation of the concept of the tabuhtabuhan, a part of panca gita which is needed in the ceremony. In Sunda (West Java), there is never any gamelan orchestra and repertoire that is specifically dedicated to honour an event, important person, or create an atmosphere such as the gendhing pakurmatan in Central Java and Bali. The only repertoire that has similar musical structure and external function of the gendhing pakurmatan of Central Java is gendhing Bêboyongan. The shape and structure of this gendhing is similar to gendhing Monggang in Central Javanese karawitan music, which is usually used to accompany the bride. In Sunda, there are no forms of gendhing used pragmatically for admiration purposes to be found. The ensemble of gamelan dêgung, ajêng, and kromong are used for various purposes of reverence, but it is not means gamelan dêgung, ajêng, and kromong and all of its repertoire is specific term of admiration21. Supanggah has mentioned gendhing gereja22 and gendhing santiswaran23 as gendhing for expressing the depth of spirituality and religiosity. Lately it also emerged a new musical genre with karawitan music as a base, namely sholawat campurngaji24. In Bali, all forms of 20 Yasa, I.K. 1991. Gendhing-gendhing Dalam Upacara Memungkah di Pura Dadia Agung Pasek Bendesa Tonja. p. 1-4. 21 Cucup Cahripin, interview 20 September 2008. 22 Supanggah. 2007. p. 108. 23 Supanggah. 2007. p. 133. 24 Sunarto, B. 2006. Sholawat Campurngaji: Musikalitas, Pertunjukan, dan Maknanya. Tesis S2. ISI Surakarta. p. 75-228. musical expression in karawitan music which is used for yatnya ceremonies always have a certain dimension associated with the “meaning” of the depth of spirituality and religiosity. Meanwhile in Sundan, the tarawangsa instruments and goong rèntèng have a major role in various ceremonies, and depitc the depth of spirituality and religiosity in Sundanese rural communities. It is especially “old” spirituality and religiosity that are associated with the belief of local communities who are still steeped in animism, dynamism and Hinduism25. As described by Sasaki, it appears that musical expression presented with tarawangsa and goong rèntèng is never separated from a variety of ceremonies, such as ceremonial worship of dewi pohaci (goddess of pohaci), dewi sri (goddess of sri) and ancestor or ancestral spirits26. Meanwhile, in the spirituality of Islam, it is found the rebana music (music of tambourines) or sholawat music with vocals character that uses musical construction of karawitan music. There are several types of gendhing in Central Java that have the function of defining the founding aesthetics of other art genres. Those are (1) gendhing wayangan, (2) gendhing kêthoprak, (3) gendhing tayub, (4) gendhing langêndriyan, and (5) gendhing bêksan27. There are similarities in the Sundanese music culture, because it also has gendhing of sejak tari, gendhing of metakpusejak wayang and so on. Gendhing as well as in Bali, beside there is gendhing pêtêgak or musical concert, it found also other types of gendhing for special purpose, those are gendhing for dance and puppets. It is proved by the existence of specific barungan (ensemble) for arja dance-drama, i.e.: gamelan pêngarjaan or gamelan gêguntangan. Specific gamelan for legong dance uses gamelan palégongan. Gamelan pêgambuhan is normally used specifically to accompany the presentation of gambuh dance. F. New Creation of Karawitan Music Essentially, new creations of karawitan music are not diametrically opposed to the classical/traditional karawitan music. The only thing that characterizes the difference between classical/traditional and new creations of karawitan music is simply when and who created a work. Most people understand karawitan to be the old works of classical/traditional karawitan music, which were created more than one or two centuries ago. The composers who created the musical genre of classical/traditional karawitan are often anonymous. The new creations of karawitan music are those that are created now, during the contemporary period, whose composers are known. Since the orging of a work is clear, so its form can be used to understand the music and be related to its quality, integrity, aesthetic tendencies, patterns of thought, and orientation of values, as they have been shared expressed by the composer. Meanwhile, a form of classical/traditional karawitan music the relationship marker of aesthetic tendencies, patterns of thought and cultural orientation of values which is held by the followers or devotees. The form of new karawitan is a new musical composition with its own form, structure and treatment. It may be a sort of reconstruction, reinterpretation, modification and/or deconstruction of the existing forms, structure, and musical treatment. Yet, it is likely that the new creation is a new musical composition without any reference to the traditional/classic. It rather follows the tendency of some new aesthetics that the composer leads. Hence, new karawitan is not something generated from the tradition whose time of composition and composer cannot be tracked down. In new karawitan music, the time of composition and composer can can be obviously be identified. 25 Caca Sopandi, interviewed 23 September 2008. Sasaki, M. 2007. Laras Pada Karawitan Sunda. P4ST UPI. Bandung. p. 113-230. 27 Supanggah, R. 2007. p. 139. 26 It iss time for the creation of the contemporary one, running along with the scholars making scientific endeavors to study them as their object. New forms of karawitan are characterized by their rich repertoires and their creative nature containing an aesthetic nuanced with (1) classic/traditional, (2) popular, (3) reinterpretation, and (4) experimental. 1. New Karawitan with their Classic/Traditional Nuance A manifestation of a traditional/classic nuance in new karawitan can be seen from its musical composition properties or the gêndhing that form its repertoire. An inherent property of it is the improvised interpretation made by its pêngrawit (instrument players) to the arrangement of balungan gêndhing (musical skeleton of the composition in karawitan music) with their ability to use céngkok (melodic patterns), the song pattern or the melodic arrangement and some variety of musical treatment vocabularies28. According to Sumarsam (year or footnote), balungan gêndhing is an abstraction of the song depth in karawitan, which is felt by the pêngrawit29. Thus, balungan gêndhing ca essentially can be perceived as an abstract melodic arrangement—a raw material idea which has not been completely musical30. The relation between the improvised interpretation and the balungan gêndhing fully known to the composer’s, thus this knowledge leads him/her to create compositions only by describing its balungan gêndhing. The composers decides to make such a creation because they believe the pêngrawit can understand their pieces’ essential elements, and serve as a guide when taking artistic action through their musical expression. Here I describe an example of a new gendhing with traditional/classic nuance that was created by pêngrawit that is very well known in Central Java. That is Lelagon “Ngimpi”, which is still uses the form, structure, vocabulary, and musical treatment of conventional gendhing, or conventional music composition. Ngimpi, Ketawang, laras Pelog, pathet Nem. Buka Celuk (begins with a single vocal) . . . . j.! @ j.7 ! . j.@ j!6 5 Sri-pat sri-pit lèmbèhané Balungan Gendhing: [ . . . . . . . . 2 2 ! 2 1 1 6 1 6 6 5 6 5 5 6 5 3> n5 3 n5 5 n3 3 n5 . . . . . . . . 5 5 1 5 j.4 j43 j.4 5 mrak kê – simpir p1 p1 p5 p1 6 2 1 2 5 1 5 5 Vocal Notation: _ . . . . _ j.! @ j.7 ! _ . j.@ j!6 5 Sri-pat sri-pit lèmbèhané 3 2 2 2 g2 g1 g1 g1 ] Swk./Stop _ j.4 j43 j.4 5 _ mrak kê – simpir _ . . . . _ j.4 5 j56 1 _ j.3 2 j.k15 5 _ j.2 2 j13 2 Gandhês luwês wi-ra - ga – né _ . . . . _ j.! @ j.7 ! _ . j.@ j!6 5 Sè-dhêt singsêt bêsus a-nga - _ ang-lam-lam-i _ j.4 j43 j.4 5 _ di bu – sã - nã _ . . . . _ j.4 5 j.6 1 _ j.3 2 j.k15 5 _ j.3 j2k.1 j.u 1_ 28 Sunarto, B. 2006. Sholawat Campurngaji: Musikalitas, Pertunjukan, dan Maknanya. Tesis S2. ISI Surakarta. p. 120. 29 Sumarsam. 2002 Hayatan Gamelan: Kedalaman Lagu, Teori & Perspektif. Surakarta: STSI Pers. p. 41. 30 Sunarto, B. 2006. Sholawat Campurngaji: Musikalitas, Pertunjukan, dan Maknanya. p. 120. Dasar a-yu _ . . . . _ 6 6 j!7 6 Tak ca- kêt-i _ . . . . _ ! ! j.6 5 O-ra srãntã tan ku – ci -wã mak-sih kê-nyã _ j.! 7 j.6 6 _ j.6 6 j.k43 3 _ a-duh mèsêm sêpêt madu _ j.1 1 j15 5 tak gandhèng _ j.3 j2k.1 j.u 1_ ma-lah gu - mu-yu _ . . . . _ j.! @ j.7 ! _ . j.@ j!6 5 Ka-ton bungah _ j.4 j43 j.4 5 _ kênyã kang pin – dhã hap – sa - ri _ . . . . _ j.4 5 j.6 1 _ j.3 2 j.k15 5 _ j.3 j2k.1 j.u 1_ Swk./Stop Ku-ci-wa-né ka bèh ma - u amung ngimpi Their artistic action, as shown in the above notation, are executed by interpreting the balungan gêndhing, i.e. by identifying the melodic contour or sèlèh (heavy or strong accent that usually exist in final melodic pattern) of balungan gêndhing, then implementing the céngkoks, or song patterns or the melodic arrangement produced by the combination of melodic arrangement and the musical treatment vocabularies. Unfortunately, in this very short paper the céngkoks cannot be described here. 2. New Karawitan with their Popular Nuance New karawitan has some popular colors, embedded by the repertoires containing the musical characters which have been wide-spread and known by society—a mass culture31. Among such kinds are the new karawitan with its sub-repertoire types of (1) langgam, (2) ndangndut, and (3) popular song. The first type is the repertoire containing forms and elements of music like the langgam in keroncong music. The keroncong songs generally have four types of forms, i.e. (1) the pure keroncong, (2) the langgam, (3) the stambul songs, and (4) other songs with structures distinct from the three. The second has some forms and elements of the ndangdut music. The last type with its popular color always has some musical construction which (1) applies a diatonic mode (2) borrows the western musical system in its musical treatment, (3) has a homophonic melodic accumulation. In realizing and implementing the diatonic mode of the Western musical system, and homophonic melodic accumulation, it been presented using instruments that commonly used in Western music. Some commonly used Western music instruments are (1) a drum kit, drum set, or trap set (2) an electronic keyboard, (3) a guitar, and (4) a bass guitar. A drum set is a collection of drums and other percussion instruments set up to be played by a single player that consists of (a) a snare drum, mounted on a specialized stand, placed between the player's knees and played with drum sticks (which may include rutes or brushes); (b) a bass drum, played by a pedal operated by the right foot; (c) A hi-hat stand and cymbals, operated by the left foot and played with the sticks, particularly but not only the right hand stick; (d) one or more tom-tom drums, played with the sticks; and (e) one or more suspended cymbals, played with the sticks, particularly but not only the right hand stick. An electronic keyboard is digital keyboard instrument that has major typical components. They area (1) a musical keyboard, (2) an interface software, (3) a rhythm & chord generator, (4) a sound generator, and (5) an amplifier and speaker. This means that this instrument with the plastic white and black piano-style keys which the player presses is connected the switches, which triggers an electronic note or other sound. Most keyboards use a keyboard matrix circuit to reduce the amount of wiring that is 31 Sunarto, B. 1987. “Kehidupan Karawitan di Tengah Kebudayaan Massa”. Paper discussed on Student Seminar of ASKI Surakarta. p. 18-22; Mack, D. 1995. Apresiasi Musik Populer. Yogyakarta. Yayasan Pustaka Nusatama. p. 33. needed. This instrument has a program, embedded in a computer chip, which handles user interaction with control keys and menus, which allows the user to select tones (e.g., piano, organ, flute, drum kit), effects (reverb, echo, telephones or sustain), and other features (e.g., transposition, an electronic drum machine). It also has a software program which produces rhythms and chords by the means of MIDI electronic commands. Furthermore, it has an electronic sound module typically contained within an integrated circuit or chip, which is capable of accepting MIDI commands and producing sounds. This instrument also has a lowpowered audio amplifier and a small speaker that amplify the sounds so that the listener can hear them perfectly. Picture 21: Drum Set used to accompany Gamelan Ensemble http://sukolaras.wordpress.com/tag/mp3-campursari/ Picture 22: Guitar, Guitar Bass, and double Piano Keyboard used to accompany Gamelan Ensemble The characteristic of new karawitan music with nuance of popular nuance is related to the spread of popular music with their publication via the mass electronic media, cassettes, CDs, or commercial VCDs. Furthermore, the new karawitan composition is undertaken for a commercial reason, oriented to the entertainment purposes. The tendency gives rise to lyrics that are written following basic emotion with the application of simple melodic phrases rather than on something mature and artistically treated. Here is one of the more popular songs in the pop music of Java, which is then processed into karawitan, i.e. song of “Cinta Tak Terpisahkan” created by Dikin. “Cinta Tak Terpisahkan” By Dikin 3. New Karawitan and its Reinterpretation (Karawitan Gagrag Anyar) This type of new karawitan refers to pieces created by utilizing the musical expression form of traditional/classic pieces as their base. Their repertoire is relatively the same as those of classical/traditional karawitan. The salient difference is in their musical treatment and expression. The repertoire treatment of this genre is by reinterpreting the existing musical forms and treatments as those produced by the classic. Their creation not only relies on the improvised interpretation by the pêngrawit, but rather on the development of the creativity taken through (1) the crossed musical style, (2) the processing of tempo, rhythms and dynamics, and (3) the addition and the reduction of the various musical treatment types. This new karawitan is not perfectly new, despite its new forms of expression. In fact, these pieces are new creation made by modifying old repertoires by using new treatment variations which are accepted in the classic/traditional style music of expression. Hence, the new karawitan a color reinterpretation is karawitan which resulted from the artistic tolerance of creativity and the violations of the musical treatment from their cultural convention, undertaken by the composers to the classical/traditional works. 4. The New karawitan with an Experimental (Explorative) Nature This type of karawitan is to so-called contemporary karawitan. The dominant character of this genre is no longer classical, interpretative, and traditional, but it is strongly an avantgarde. One of aspect of avant-garde in art is that it be developed by the educated intellectuals applying new concepts and/or some experimental efforts. The picture below is an example of musical instruments for avant-garde karawitan music, created by Aloysius Suwardi. This is a picture of the modified gender barung instrument, which is processed using the vibration processing machine so that the sound produced is different from conventional gender. Its consequence, how to process and work on this musical expression is also different from conventional karawitan music. Picture 23: Gendér instrument with vibraphone character or Gendér Jangkung The contemporary music of karawitan, related to their concept development, is manifest in two of the three natures of the existential, which are: 1) The founding concept and/or idea and musical character of the karawitan is primarily on the existential concept more than the performance of the art work as its expressed form. 2) The founding concept and/or idea and musical character for its musicality puts so much priority on the musical existence as its form of expression that its artistic orientation is emphasized on the value of the artwork. 3) Two points above relies on the typical and personal experience of each individual composer. Existentially, each piece in contemporary karawitan always has either the first characteristic or the second in mutually exclusive way. The third is always found in every contemporary work. This means that the concept, idea and the experience of each individual is a very critical element, which determines the medium and the musical construction of the contemporary karawitan empirically present. The notion of “experimental” or “contemporary” refers neither to the recent development of the karawitan music, nor does it indicate the growth or the rejuvenating movement in it. It does not simply imply the personal styles beyond the classical/traditional mainstream in its relation to the emerging intercultural issues. The contemporary karawitan is; 1) Karawitan whose existence is supported by the concepts representing the thought of composer when designing his/her musical character which influence of intellectualism, inspiration and subtle impressive internalization. 2) Karawitan demonstrating artistic vocabularies as musical “expression language”, with its progressive nature since the composer intentionally escapes the “expression language” bonded to the cultural tradition and rules. 3) Karawitan whose musical formats are designed by applying the avant-garde or experimental techniques with their unlimited existence. It offers something far from the consideration of the marketing purposes, to make the works easy to sell. Based on the elaboration above, it is clear that the contemporary karawitan is the one having a developed achievement; it has gone beyond the traditional convention. In its advance, this genre poses an artistic model which is never touched in the mind of classical/traditional vocabularies. The reason is that it has a creative spirit manifested by an open-form system of composition toward any orientation, tendency, and artistic value; it is freely open. G. Conclusion The above discussion has shown that Indonesian karawitan has two great musical genres, i.e., the classical/traditional and the new creation. The genre of classic/traditional karawitan is always the foundation for the development of any type of karawitan. Another genre is the product of the developing endeavours, consisting of four main types, i.e. new karawitan colored by 1) the classic/traditional, (2) the popular, (3) the reinterpretated and (4) the experimental. In the discourse of Indonesian karawitan, the experimental karawitan is called contemporary karawitan, because it is avant-garde in nature. It is represents the pushing of boundaries beyond what is accepted as the musical norm or the musical status quo, primarily in the musical-culture realm. The notion of the existence of the avant-garde karawitan music is considered by some to be a hallmark of modernism, and posibly an odyssey of the mind area of postmodernism. H. Bibliography Avtar Veer, R. 1999. Theory of Indian Music. New Delhi. Pankaj Publication. Bagchee, S. 1998. Nãd: Understanding Rãga Music. Mumbai. Eshwar. Curchman, C.W. dan Russel L. Ackoff. 1970. Methods of Inquiry: An Introduction to Philosophy and Scientific Method. St. Louis: Educational Publishers. Djumadi, n.d. “Sejarah Singkat SMK Negeri 8 Surakarta”, Manuskrip. Ferdinandus, J.P.E. 2001. Alat Musik Jawa Kuno. Kajian Bentuk dan Fungsi Ansamble Abad IX-XV Masehi. Yayasan Mahadika. Yogyakarta. Ghosh, N. 1978. Fundamentals of Raga and Tala with a New System of Notation. Nikhil Ghosh Sangit Mahabharati. Bombay. Hardosukarta, S. 1978. Titi Asri. Alih aksara dan Ringkasan oleh A. Hendrato. Jakarta: Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan - Proyek Penerbitan Buku Bacaan dan Sastra Indonesia dan Daerah. Haryono, T. 2001. Logam dan Peradaban Manusia. Yogyakarta: Philosophy Press. Haryono, T. 2008. Seni Pertunjukan dan Seni Rupa dalam Perspektif Arkeologi Seni. ISI Press Solo. Surakarta. Humardani, S.D. 1982. “Beberapa Pikiran Dasar Tentang Seni Tradisi Latar Belakang Pengembangan Seni Tradisi Pertunjukan”. Makalah. Dipresentasikan dalam Sarasehan Kesenian, diselenggarakan oleh Proyek Pengembangan Kesenian Jawa Tengah (PKJT). Lindsay, J. 1992. Javanese Gamelan: Traditional Orchestra of Indonesia. Singapore ; New York : Oxford University Press. Mack, D. 1995. Apresiasi Musik Populer. Yogyakarta. Yayasan Pustaka Nusatama. Natapradja, I. 2003. Sekar Gendhing. Bandung: PT. Karya Cipta Lestari. Purwarsito, A. 2002. Imageri India. Studi Tanda dalam Wacana. Surakarta. Pustaka Cakra. Soetrisno, R. 1976. Sejarah Karawitan. Akademi Seni Karawitan Indonesia. Surakarta. Sopandi, C. 2006. Gamelan Selap: Kajian Inovasi Pada Karawitan Wayang Golek Purwa. Tesis S-2. Program Studi Pengkajian Seni. Institut Seni Indonesia (ISI) Surakarta. Sukerta, P.M. 2004. Perubahan dan Keberlanjutan dalam Tradisi Gong Kebyar: Studi tentang Gong Kebyar Buleleng. Disertasi Doktor. Denpasar: Universitas Udayana. Sumarsam. 2002 Hayatan Gamelan: Kedalaman Lagu, Teori & Perspektif. Surakarta: STSI Pers. Sunarto, B. 1987. “Kehidupan Karawitan di Tengah Kebudayaan Massa”. Makalah untuk Diskusi Mahasiswa ASKI Surakarta. Sunarto, B. 2006. Sholawat Campurngaji: Musikalitas, Pertunjukan, dan Maknanya. Tesis S2. ISI Surakarta. Supanggah, R. 1983. “Pokok-Pokok Pikiran tentang Garap”, paper yang dipresentasikan dalam diskusi pengajar dan mahasiswa Jurusan Karawitan ASKI Surakarta, Surakarta: ASKI. Supanggah, R. 1994. “Gatra: Inti dari Konsep Gêndhing Tradisi Jawa” dalam Wiled, Sekolah Tinggi Seni Indonesia (STSI) Surakarta, I/1: 13-26. Supanggah, R. 2002. Bothekan Karawitan I. Jakarta: Ford Foundation & Masyarakat Seni Pertunjukan Indonesia. Supanggah, R. 2005. “Garap: Salah Satu Konsep Pendekatan/Kajian Musik Nusantara” dalam Menimbang Pendekatan Pengkajian & Penciptaan Musik Nusantara. Surakarta: Jurusan Karawitan STSI Surakarta. Widodo, T.S. 1997. Belajar Menyanyi dengan Not Blok 1. Yogyakarta: Penerbit Kanisius. Yasa, I.K. 1991. Gendhing-gendhing Dalam Upacara Memungkah di Pura Dadia Agung Pasek Bendesa Tonja. Laporan Penelitian. Sekolah Tinggi Seni Indonesia (STSI) Surakarta. Biodata Bambang Sunarto graduated from the Institute Indonesian Arts of Surakarta, and received a doctoral degree in the science of philosophy at the University of Gadjah Mada Yogyakarta. He is a contemporary music composer whose works of music have been performed in various venues such as in India, Thailand, and Philippines. His scientific articles relating to music have been published at various journals such as Asian Musicology, Panggung, Dewa Ruci, Keteg, and Terob. Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts (IGNCA) has published his book titled Between Sangeet and Karawitan: Comparative Study on India and Indonesian Music. He has also published his new book in Indonesian about the methodology of arts creation entitled the Metodologi Penciptaan Seni. IGNCA has also funded his research relating to the aesthetic concept of Indian and Indonesian music. In 2012, DAAD (Deutscher Akademischer Austausch Dienst), German academic exchange service provided the funding to conduct research on the University Music of Lubeck in German the epistemology of music creation. He is currently associate professor at the ethnomusicology department of the Institute Indonesian Arts of Surakarta.