* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download file (Parkinsons Disease Topic

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

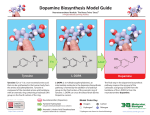

PARKINSON’S DISEASE Stefanie L. Drahuschak PharmD Candidate 2014 OBJECTIVES Describe the etiology, epidemiology, and clinical manifestation of Parkinson’s Disease (PD) Determine appropriate first-line therapy for Parkinson’s Disease Determine appropriate adjunct therapeutic agents for Parkinson’s Disease List treatment complications and understand how to augment therapy accordingly EPIDEMIOLOGY ~2% lifetime risk of PD 4% if positive family history The number of patients diagnosed with PD per year ranges from 10 per 100,000 people aged 5059 and 120 per 100,000 people aged 80-89 Prevalence of PD increases with age Usual age at time of diagnosis ranges between 55 and 65 years old A higher incidence is reported among males Male to female ratio of 2:1 EPIDEMIOLOGY Risk factors (possible) Protective factors (consistent evidence) Living in rural area, drinking well water, chronic exposure to pesticides and/or heavy metals (iron and manganese) Cigarette smoking, caffeine consumption Genetic factors More likely play a role if develop PD before age 50 GENETICS A growing number of single gene mutations have been identified Six genes have been identified (11 mapped) SNCA, UCH-L1, PRKN, LRRK 2, PINK 1, DJ-1 genes With the exception of LRRK 2, these genes only account for a small number of PD patients LRRK 2 gene is the most common cause of familial or “sporadic” PD Identification of these genes have allowed for further insight into disease mechanisms ETIOLOGY Not fully understood Likely involves interactions between aging, genetic makeup, and environmental factors Two hallmark features: 1) Cell death in the substantia nigra affecting dopaminergic neurons decreases dopamine levels symptoms occur 2) Lewy bodies are present in the remaining neurons PD is usually clinically detectable when ~70-80% of neurons are depleted CLINICAL PRESENTATION Symptoms start insidiously and unilaterally T - tremor (at rest) R - rigidity (of muscles) A - akinesia/bradykinesia (no/slow movement) P – postural changes Probable PD can be diagnosed when at least two of these symptoms are present For proper diagnosis other causes must be ruled out, such as medication-induced parkinsonism CLINICAL PRESENTATION T – tremor Usually in arms/hands Patients make a pill-rolling movement with fingers and hands May subside when patient is mobile or while sleeping R – rigidity of muscles Hypomimia – mask-like appearance of face CLINICAL PRESENTATION A – akinesia/bradykinesia Slow movement throughout action/task Micrographia – writing progressively smaller Gait issues P – postural changes Most common in advanced stages of PD Increases risks of falls to patients MEDICATION-INDUCED PARKINSONISM Must rule out before proper PD diagnosis Most likely to occur with medications that act on dopamine-2 receptors Antipsychotics Antiemetics (dopamine antagonists) Phenothiazines, olanzapine, risperidone, haloperidol Metoclopromide (BBW), prochlorperazine Etc Methyldopa TREATMENT GOALS Preserve motor and non-motor functions Be able to perform activities of daily life Improve mobility Minimize adverse effects of PD treatment Improve non-motor issues such as cognitive impairment, depression, fatigue, and sleep disorders. IMPROVE QOL! PD TREATMENT PD Physical and Mental Therapy MAO-B Inhibitors Pharmacotherapy Dopamine agonists Surgery Carbidopa/Levodopa MAO-B INHIBITORS Agents Rasagiline (Azilect®) Selegiline (Eldepryl®) Selegiline ODT (Zelapar®) MOA Selectively and irreversibly inhibitions MAO-B in the brain, which interferes with the degradation of dopamine leading to prolonged dopaminergic activity MAO-B INHIBITORS Duration of Action Metabolism Bioavailability Rasagiline (Azilect®) ~1 week CYP1A2 36% Primarily renally Selegiline (Eldepryl®) 24-72 hours CYP2B6 25-30% delivered over 24h 10% renal 2% fecal Selegiline ODT (Zelapar®) 24-72 hours CYP2B6 and 3A4 >> capsule / tablet Primarily renally Drug Excretion RASAGILINE (AZILECT®) Effective as monotherapy for early PD or as addon therapy for managing motor fluctuations in advanced PD Dose Adverse effects 0.5 to 1 mg once daily Generally well tolerated with minimal GI or neuropsychiatric side effects Second generation, not as well studied as selegiline SELEGILINE (ELDEPRYL®) Early PD – monotherapy can provide modest motor function improvments Advanced PD – adjunctive use can add 1 hour of “on” time Dose 5 mg PO BID Adverse effects minimal; insomnia, hallucinations, jitteriness Can worsen preexisting dyskinesias or psychiatric symptoms such as delusions Second dose given in afternoon to avoid insomnia SELEGILINE ODT (ZELAPAR®) Avoids first pass hepatic metabolism increased bioavailability Use as adjunctive therapy Decreases “OFF” time Dose 1.25 mg PO daily for at least 6 weeks; can increase to 2.5 mg PO daily based on response Adverse effects Oral irritation (10%), insomnia DOPAMINE AGONISTS Directly stimulate dopamine receptors Two subtypes 1) Ergot-containing agonists Bromocriptine (Parlodel®) Pergolide (Permax®) – no longer available 2) Nonergot agonists Pramipexole (Mirapex®) Ropinirole (Requip®) Rotigotine (Neupro®) DOPAMINE AGONISTS Nonergot dopamine agonists are useful as monotherapy in mild-mod PD or adjunct therapy to L-dopa Reduce frequency of “off” periods May allow reductions in L-dopa dose Longer half lives than L-dopa Adverse effects Nausea, confusion, hallucinations, light-headedness, lower-extremity edema, postural hypotension, sedation, vivid dreams Compulsive behaviors (gambling, hypersexuality) DOPAMINE AGONISTS Drug Initial Dose Max Dose Pramipexole 0.125 mg TID 1.5 mg TID Renal dosing: CrCl 35-59 mL/min CrCl 15-34 mL/min 0.125 mg BID 0.125 mg daily 1.5 mg BID 1.5 mg daily Pramipexole ER 0.375 mg daily 4.5 mg daily Renal Dosing: CrCl 30-50 mL/min CrCl <30 mL/min 0.375 mg every other day NOT recommended 2.25 mg daily NOT recommended Ropinirole 0.25 mg TID 24 mg/day Ropinirole XL 2 mg daily 24 mg/day Bromocriptine 1.25 mg BID 40 mg/day LEVODOPA (L-DOPA) Most effective drug for symptomatic treatment of PD drug of choice Is an immediate precursor to dopamine Able to cross the blood brain barrier Other drugs for PD are not able to Very short half-life Undergoes rapid peripheral conversion of L-dopa to dopamine Used in combination with other agents to reduce the conversion peripherally and increase L-dopa concentration centrally Regardless of initial therapy, all patients will eventually require L-dopa CARBIDOPA Peripherally-acting L-amino acid decarboxylase inhibitor Decreases the peripheral conversion of L-dopa to dopamine Increases L-dopa transported into brain Decreases peripheral side effects of dopamine (nausea) Unable to cross blood brain barrier Never used as monotherapy Increases half-life of L-dopa to 1.5-2 hours CARBIDOPA/LEVODOPA COMBINATIONS Carbidopa/Levodopa immediate release (Sinemet®) Carbidopa/Levodopa sustained release (Simemet CR®) 10mg/100mg; 25mg/100mg; 25mg/250mg 25mg/100mg; 50mg/200mg Carbidopa/Levodopa ODT (Percopa®) 10mg/100mg; 25mg/100mg; 25mg/250mg CARBIDOPA/LEVODOPA (SINEMET®) Dosing Start with 25mg/100mg one tablet TID 75 mg carbidopa/300 mg levodopa per day in divided doses 75 mg of carbidopa per day is required to sufficiently inhibit peripheral activity of L-amino acid decarboxylase Titrate up slowly based on symptoms No true maximum dose of Levodopa 200 mg carbidopa and 2,000 mg levodopa is a common maximum dose CARBIDOPA/LEVODOPA (SINEMET®) Adverse effects “Sin-emet” = without vomiting Nausea, postural hypotension, sedation, vivid dreams, dyskinesias Counseling Should be initially taken with food for a few weeks Then take 30 mins before or 60 mins after meals to avoid competition for absorption with other amino acids Move carefully from supine position (postural hypotension) MOTOR COMPLICATIONS OF L-DOPA Approximate risk of developing complications is 10% per year of L-dopa therapy Can occur as early as 5-6 months after starting therapy, especially with higher doses Possible complications End-of-dose “wearing off” “Delayed on” or “no on” response Start hesitation (“freezing”) Peak-dose dyskinesia END-OF-DOSE “WEARING OFF” Phenomenon of experiencing motor fluctuations before the next dose is due With advancing PD, duration of action of single dose shortens progressively Due to decreasing neuronal storage capability and short half-life of levodopa Therefore needs to eventually be dosed more frequently Can also add another agent (MOA-B inhibitor/DA) to help help control “off” time “DELAYED-ON” OR “NO ON” RESPONSE A delayed or completely absent onset of drug Due to delayed gastric emptying or decreased absorption in the duodenum Intervention: Take medication on an empty stomach Chew tablet or crush and drink with full glass of water Use ODT formulation “Drug holidays” may be used rarely to modify dopamine receptors Unpleasant for patient, not commonly done START HESITATION (“FREEZING”) A sudden, episodic inhibition of lower extremity motor function Interferes with ambulation and increases risk of falls/injuries Patients feel as if they are “stuck to the floor” Can be exacerbated by anxiety or obstacles (doors, turns) Intervention Could increase dose +/- add medication, but physical therapy/walking devices are more helpful generally PEAK-DOSE DYSKINESIA Involuntary movements usually involving the neck, trunk, and lower/upper extremities Associated with peak concentrations of dopamine Using lower doses of L-dopa dyskinesias will improve But PD symptoms may return increasing dosing interval or addition of another chemical Addition of an NMDA receptor antagonist (amantadine) may be helpful For severe dyskinesias, surgery may be considered ADJUNCTIVE PD THERAPY Amantadine Apomorphine Anticholinergics COMT Inhibitors AMANTADINE MOA Not fully understood Inhibits glutamate NMDA receptors releases dopamine from nerve terminals Onset of action within 48 hours Excreted unchanged in urine Provides modest early PD benefit Useful for decreasing L-dopa induced dyskinesias Dose 200-300 mg/day in early PD 200-400 mg/day in divided doses for dyskinesias AMANTADINE Adverse effects Confusion, dizziness, dry mouth, hallucinations Elderly are prone to develop confusion Counseling Take without regards to food Take early in day to avoid sleep disturbances APOMORPHINE Subcutaneous nonergot dopamine agonist Extensive first pass metabolism from SQ administration Duration of effect is ~100 minutes Creates an “on” response within 20 minutes Dose 2-6 mg per injection (about 0.06 mg/kg) $$$$$ APOMORPHINE Adverse effects Nausea/vomiting and hypotension Premedication with antiemetic is necessary Contraindicated with 5HT3-receptor blockers (ondansetron, etc) Dopamine antagonists should be avoided (metoclopromide, prochlorperazine) Trimethobenzamide would be antiemetic of choice ANTICHOLINERGICS Dopamine inhibits acetylcholine neurons Therefore, when dopamine is depleted in PD cholinergic activity increases Increased cholinergic activity is believed to contribute to tremors MOA: decrease cholinergic activity Same effectiveness at treating tremors as dopamine agonists Limited use from adverse effects Dry mouth, blurred vision, urinary retention, constipation, confusion, sedation On Beers Criteria for elderly patients to avoid ANTICHOLINERGICS Agents: Benztropine Trihexyphenidyl 0.5 to 2 mg BID 0.5 to 1 mg BID; slowly titrate to 2 mg TID Indications Treatment of tremors in patients < 65 yo To decrease rigidity To manage drooling COMT INHIBITORS (CATECHOL-OMETHYL-TRANSFERASE) MOA Reduce peripheral conversion of L-dopa to dopamine, which enhances central dopamine bioavailability Similar to carbidopa Can decrease off-time significantly by increasing L-dopa AUC by ~35% Considered more effective than SR carbidopa/levodopa in extending L-dopa effect Agents: tolacpone and entacapone TOLACAPONE (TASMAR®) First COMT Inhibitor available in US Dose 100-200 mg TID Black box warning Fatal liver injury Reserved for inadequate symptom control Need informed consent Liver function monitored q 2 weeks x 1 week, then q 4 weeks thereafter ENTACAPONE (COMTAN®) Has a shorter half-life than tolcapone Dose: 200 mg needs to be given with each dose of carbidopa/levodopa up to a maximum of 8 times/day Increase total daily “on” time by 1-2 hours Adverse effects: Brownish-orange urine, delayed onset diarrhea (no liver issues) Available in combination tablet with carb/levo SURGERY Currently considered an adjunct to pharmacotherapy for patients with uncontrolled symptoms despite an appropriate medication regimen Deep-brain stimulation (DBS) is preferred surgical method A battery-powered neurostimulator is implanted subcutaneously below clavical Provides constant electrical stimulation Very effective for suppressing tremors, but not as helpful for other PD symptoms COST CONSIDERATIONS In US, direct costs associated with PD range from $4-$8 billion per year The more severe the disease, the higher it costs to manage Falls, dementia issues, nursing facilities Minimizing costs Should use lowest effective dose Try single agents before adjunctive therapy considered NON-MOTOR COMPLICATIONS OF PD Autonomic Sleep disturbances Daytime somnolence, insomnia, RLS, fatigue, REM sleep disorder Mood issues Sexual dysfunction, orthostatic hypotension, urinary incontinence, constipation Anxiety, depression, psychosis Cognitive dysfunction Dementia SEXUAL DYSFUNCTION Occurs in both men and women with PD Less studied in women Sildenafil (Viagra®) 50 mg has been effective in the treatment of ED in PD patients ORTHOSTATIC HYPOTENSION A drop of 20 mmHg in SBP or 10 mmHg in DBP Determine if any other agents could be contributing d/c if possible Use support stocking, stand up slowly, decrease L-dopa dose if possible DAYTIME SOMNOLENCE Can be multifactoral Due to PD, medications, underlying sleep issues, mood issues Modafinil may be beneficial in improving patient’s perception of wakefullness during the day RESTLESS LEG SYNDROME Occurs in up to 20% of patients with PD Dopamine agonists (ropinirole and pramipexole) are only FDA-approved agents for RLS Carbidopa/levodopa may decrease the incidence of nighttime leg movements DEMENTIA Unknown if the etiology is similar or different in patients with PD Donepezil (Aricept®) or rivastigmine (Exelon) could be considered DEPRESSION Occurs in ~40% of PD patients Depression may be exacerbated by PD issues such as insomnia, psychomotor changes, weight changes, fatigue/loss of energy, feelings of losing control of body Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors can be used to help improve QOL CONCLUSION A cause or cure for PD still does not exist Many treatment options exist with wide patient intervariability An appropriate medication regimen can significantly improve QoL Goal of therapy continues to be maintaining functional control with minimal complications REFERENCES 1) Davie CA. A review of Parkinson’s Disease. Br Med Bull. 2008; 86: 109-127. 2) Chen JJ, Nelson MV, Swope DM. Parkinson’s Disease. In: Dipiro JT, Talbert RL, Yee GC, eds. Pharmacotherapy. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2011: 1033-1044. 3) Jankovic J. Parkinson’s disease: clinical features and diagnosis. Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr. 2008; 79(4): 368-76. 4) Chen JJ. Anxiety, depression, and psychosis in Parkinson’s Disease: Unmet needs and treatment challenges. Neurol Clin. 2004; 22(3): 63-90. 5) Obeso JA, Rodriguez-Oroz MC, Goetz CG, et al. Missing pieces in the Parkinson’s disease puzzle. Nat Med. 2010; 16(6): 653-61. 6) Lees AJ, Hardy J, Revesz T. Parkinson’s Disease. Lancet. 2009; 373: 2055-66. 7) Rihmer Z, Seregi K, Rihmer A. Parkinson’s disease and depression. Neuropsychopharmacol Hung. 2004; 6(2): 82-5. QUESTIONS?