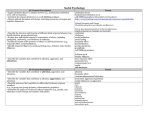

* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Is altruism encoded in our genes

Discovery of human antiquity wikipedia , lookup

Anatomically modern human wikipedia , lookup

E. O. Wilson wikipedia , lookup

Darwinian literary studies wikipedia , lookup

Evolutionary psychology wikipedia , lookup

Human evolutionary genetics wikipedia , lookup

Behavioral modernity wikipedia , lookup

Origins of society wikipedia , lookup

Social Bonding and Nurture Kinship wikipedia , lookup

Evolutionary origin of religions wikipedia , lookup

Inclusive fitness in humans wikipedia , lookup

Is altruism encoded in our genes? http://www.stnews.org/News-2891.htm New studies suggest chimpanzees may also be altruistic. By William Orem (July 4, 2006) Caring more: Studies show chimps can be altruistic. (Photo: Lea Maimone/Morguefile) The ability to think selflessly has been taken for some time to represent a specifically human trait. Although it’s true that domestic animals demonstrate affection and may even come to an owner’s aid, researchers working on altruism are wary of drawing broad conclusions from such events. A technical definition of altruism might include, for example, a willingness to provide help without either the experience or expectation of reward — conditions difficult to replicate even in a laboratory setting. Altruism may also require a complex of fairly high-level cognitive abilities, such as intentional state attribution, which involves the recognition that an entity other than oneself seeks to fulfill a plan. The presence of such skills in nonhuman species is not clear. A study recently conducted at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, however, says that altruistic impulses may exist in primates other than humans. It also brings to light some surprising information about human altruism: It appears even in prelinguistic toddlers. “It was surprising to us that this was so obvious at this early age,” said Felix Warneken, co-author of the study with Michael Tomasello. Warneken and Tomasello observed both children and chimps in various situations where the possibility of giving aid arose. While hanging a sheet on a line near their subjects, the experimenter would suddenly drop a peg out of reach. For 10 seconds he reached unsuccessfully for the peg. After that he would initiate eye contact and, after another 10 seconds, use the vocalization: “My peg!” In 84 percent of the human cases, toddlers assisted the experimenters in retrieving the item even before eye contact was established. Surprisingly, chimps in similar situations demonstrated a helping response as well. They not only tended to aid their caretaker in retrieving dropped objects but were also more likely to do so when the caretaker reached for the item, evincing a need. In no instance was the helping behavior met with a reward. It is here, though, that wariness about drawing broad conclusions comes into play. “The [Warneken and Tomasello] papers show that chimps sometimes provided instrumental help to adults that they knew very well,” said Joan Silk, an anthropologist at UCLA and the author of numerous studies on the evolution of primate behavior. “This is very interesting, and well worth reflecting on. However, it is not clear from these experiments what motivated the chimps to behave the way that they did. Were they motivated out of concern for their caretakers? Did they perceive this as a game or a chore? Had they been asked before to retrieve items and been rewarded for this? Had they been conditioned to please human caretakers?” Warneken said he is aware of this type of concern. “It could be these kinds of behaviors are confined to a relationship with a person they know well,” he said. “We are currently studying other chimpanzees to see whether they help a human they never interacted with before.” The distinction may well be a significant one, as the human children showed a robust tendency to help even strangers. Although by no means ubiquitous, this predilection to aid strangers is generally found in human adults. Individual instances include a passer-by automatically stooping to help up a senior citizen who has fallen. Group examples include blood drives, food drives and the willingness of large numbers of people to donate resources to the victims of natural disasters in other countries. Indeed, to many the stipulation that giving occur between strangers is a prerequisite for true altruism. Warneken and Tomasello’s data are only the beginning of a new picture, but they are suggestive of a model whereby predisposition to pro-social behavior — even toward strangers — is hard-wired into at least some primates. This model, in turn, would point toward a much more ancient pedigree for altruism than was formerly believed, reaching as far back as the common ancestor between humans and chimps. If so, that would mean a basic form of altruism has existed not for tens, or even hundreds of thousands of years, but for some six million. “[Recent] studies seemed to indicate that helping behaviors in general were totally human-specific,” Warneken said. “Now it seems the question is open again. The roots of altruistic behavior seem not to originate in humans only but go further back in evolutionary time.” Is selflessness even possible? The hypothesis comes with strings attached, however, as evolutionary biologists have had a difficult time imagining how true selflessness could have come about. Phylogenetic models recognize the pressure that favors selfish action. It is self-directed behavior in general that links with survival and thus can be translated into heritable traits. In short, a tendency to give away one’s food to strangers, exert one’s energy to benefit strangers and cede reproductive opportunities to strangers should soon disappear. Nevertheless, natural selection works on the gene pool, not the individual. This distinction has led some researchers to suspect roundabout mechanisms by which selflessness may become encoded by virtue of being beneficial to multiple parties. One form of such an arrangement is reciprocal altruism, in which giving is linked to getting. “I believe the [behaviors] glossed by ‘reciprocal altruism’ were favored by natural selection and so, in some sense, ‘selfish,’” said James Moore, an associate professor of anthropology at the University of California, San Diego. “The caveats are that this says nothing about the emotional or cognitive experience of ‘selfishness’ and that ‘selfish origin’ can include original payoffs to offspring or other kin.” In other words, genetic analysis leaves aside the issue of whether we feel such behavior is “good” and asks only how it might have evolved. In this light, a father who deprives himself of something to benefit his daughter still increases the likelihood that his own genetic material will continue on, and so is behaving selfishly in an evolutionary sense. One would expect this kind of concern for kin welfare to become encoded, and more complex feedback loops may well have evolved that encompass strangers in a similar way. Is selflessness social? Another possibility is that altruism may represent an emergent property of social groups, one that is pinned only to genetics in terms of a predisposition. Such an option would allow for higher-level reinforcement of pro-social behavior among species with sophisticated social networks. Such selective pressure would occur late in the evolution of the species, “but not so late that there might not have been further genetic selection favoring tendencies toward altruism,” Moore said. “An important angle on this is that I agree with Darwin’s initial idea that the levels of altruism that we see in humans are likely to have evolved through group selection,” he added. “In that sense, altruism would be a genetically grounded emergent property of groups.” Warneken allows for this possibility as well. “Humans at least developed cultural systems in which altruistic behaviors are sustained and asocial behaviors are punished, and these groups then have advantages over other cultural groups,” he said. Silk places particular emphasis on the social dimension and its connection to humanness. “When animals cooperate in a strictly contingent way — I’ll scratch your back, if and only if you scratch mine — then self-interest provides a sufficient explanation for the behavior,” she said. “That is, self-interest alone would be enough to produce this kind of reciprocal cooperation.” However, she added, the data does not demonstrate an obvious preponderance of this “contingent reciprocity” in nonhuman primates. It is an absence that may point toward the importance of more complex forms of sociality. “My work on the social behavior of baboons convinces me that the most profound link between human and nonhuman primates is the fundamental importance of social bonds,” she said. “We now have evidence that female baboons form close, stable and egalitarian social bonds with other females and that females who are most socially integrated enjoy reproductive advantages. For both humans and other primates it seems crucial to be part of welldefined social networks and to live in a social world.” The quest to understand that social world of primates goes on, a quest that is ultimately about understanding both what ties us to other species and what makes us unique. “More than other primates, humans seem to have evolved the capacity for real concern for the welfare of others, a concern that is reflected in our capacity for friendship, our preference for fair outcomes and our willingness to make sacrifices on others’ behalf,” Silk said. William Orem is science editor at Science & Theology News.