* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download The Virtual Woodland

Plant defense against herbivory wikipedia , lookup

Biodiversity action plan wikipedia , lookup

Photosynthesis wikipedia , lookup

Conservation agriculture wikipedia , lookup

Biological Dynamics of Forest Fragments Project wikipedia , lookup

Natural environment wikipedia , lookup

Sustainable agriculture wikipedia , lookup

Theoretical ecology wikipedia , lookup

Habitat conservation wikipedia , lookup

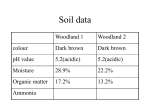

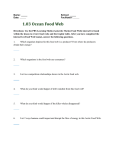

The Virtual Woodland Teachers’ Notes National Curriculum Links Science Sc1 ideas and evidence in science 1a Sc2 life processes and living things Green plants as organisms 3a, 3b Variation, classification and inheritance 4a, 4b Living things in their environment 5a Breadth of study 1a, 1c, 1d, 1e, 2a Developing skills of enquiry and communication 2a, 2b Geography Geographical and enquiry skills 1a, 1b, 1e Knowledge and understanding of places 3a, 3d, 4b Knowledge and understanding of environmental change and sustainable development 5a, 5b Breadth of study 6j Literacy Group discussion and interaction (3) ICT Exchanging and sharing information 3b, 3c Reviewing, modifying and evaluating work as it progresses 4 Breadth of study 5 Citizenship Knowledge and understanding about becoming informed citizens 1c Developing skills of participation and responsible action 3a, 3b, 3c Introduction The Virtual Woodland program is based on the winning idea submitted by Daryl Spencer of Castle Carrick Primary School, Cumbria to Sellafield Ltd's Primary Whiteboard Awards 2007. Daryl's idea aimed at supporting upper KS 2 children's learning about the complex relationships between organisms which shape a habitat. By investigating the connections between living things and their environment, the resource seeks to stimulate discussion of how to protect the environment, how living things adapt to specific habitats and how food chains and webs operate. Specifically, the program provides opportunities to demonstrate: * the effect of changes in environmental factors * food chain links between species within a habitat * how removal of a species may impact significantly on many more species The software is intended to bring the natural habitats of a woodland environment into the classroom in order for pupils to develop their understanding and awareness of the issue of climate change. The resource will be of great benefit to urban schools which do not enjoy easy access to the countryside, and will also benefit schools that are able to integrate fieldwork into their curriculum by developing their pupils' understanding further. 1 The Virtual Woodland Teachers’ Notes Using the Program The Virtual Woodland can be the basis for a teacher-led, whole-class interactive whiteboard activity. Alternatively, it can be used in an ICT suite or on an individual computer as an investigation activity driven by pupil-led hypotheses. To make the interactive lessons both attractive and informative, the objectives are set in the context of a mixed deciduous woodland. Each season can be selected from an opening menu, plus options to explore the effects of climate change on woodland and a woodland food web. On-screen arrows allow movement through 3 layers of the wood. On each layer there are buttons which open information boxes about the trees, plants, animals, birds and insects within the wood at that time of year. Information Boxes Boxes can be moved by clicking on the orange button in the top left corner of a box, then clicking where you want to move it to on-screen. To close the box, click on the red cross in the top right corner. Boxes can be brought to the fore by clicking on any part of them that is visible. Text which will open another box is shown in blue. Woodland Ecosystem The physical characteristics of a woodland ecosystem are limited by geographical barriers, the availability of water, daylight length, temperature and soil chemistry. These combined with other physical conditions determine the biological components, the types and numbers of plants and animals and their distribution. The distribution of resources (food) available to plants and animals creates competition between species. The species in a woodland occupy layers or levels in it. These are known as trophic layers. Competition exists within and between species, one with another. If a species is more efficient than another it should be able to command more of an available resource and, accordingly, species have developed strategies (adaptation and variation) to minimise competition. Feeding Relationships Trees are organisms which photosynthesise carbon dioxide and water by the energy in sunlight to build simple sugar molecules and combine them to make cellulose, lignin (wood), and oxygen, a by-product they release into the atmosphere. This process is called carbon fixing. Animals cannot fix carbon. Animals can only live by directly or indirectly consuming primary producers. The energy fixed by the primary producers is converted into products, including plant material, which make the energy available to consumers as it passes through the trophic layers. These species food chains combine to produce trophic food webs. The energy passed along the food web is proportionally reduced as it proceeds from the bottom to the top of the web. Generally the number of individuals decreases at each trophic level, so it may follow that shorter food chains lose less energy. The nearer a consumer is to the beginning of the food chain, the greater the amount of available energy. However, some animals occupy several trophic levels to feed directly and indirectly on plants and also on other animals. These are the omnivores. Some species consume other creatures and are known as predators. Their food is called their prey. It can be seen, therefore, that such a relationship is dependent on population size. Other factors limiting population size include sunlight (daylight hours), space, shelter, availability of mates and direct or indirect human activity. Feeding relationships are complex. Food chains are interconnected to form food webs. If the population of one organism in the food web is altered, either by natural events or because of human activity, other organisms are also affected. Food chains and webs do not indicate the numbers of individuals in a community at each trophic level. The most accurate representations of feeding relationships in a community describe the amount of energy flowing through each trophic level at a given time. Numbers, which are season and weather sensitive, are calculated or estimated using periodically taken samples of organisms from each trophic level and calculating their biomass (dry weight) and energy measurements to produce a pyramid of numbers. The producers (green plants) are at the bottom of this pyramid and at the apex are the top carnivores. 2 The Virtual Woodland Teachers’ Notes The soil is of great importance and establishes the fundamental mechanism controlling the structure of the woodland. Top predators, like all other biological components of the woodland, ultimately die and are scavenged upon, or merely rot, and are broken down into the soil by decomposers, mainly fungi and bacteria, into simple organic molecules which are taken up by the producers from the soil. Oxygen, nitrogen, phosphorus, sulphur and other nutrients are cycled between the components of the woodland ecosystem, i.e. between the soil and the atmosphere. Dead organic matter includes energy available to detrital food webs, and decomposition completes the cycle of matter by breaking down complex organic materials and releasing carbon as respired carbon dioxide, nutrients and heat. This process is limited by larger detritivores such as earthworms, fungi and bacteria, with temperature being critical to the speed of the process. Primary production is controlled by the availability of water, daylight length, ambient temperature and the nutrition available to the plants. Some of the carbon dioxide taken up by plants is returned to the atmosphere through the process of respiration. Respiration releases the energy stored in organic matter and provides energy for plants to sustain themselves. Remaining carbon is stored in the structures of the plant - leaves, roots, seeds, wood and branch tissues. This is the biomass of a plant. Herbivores consume primary producers and are, in turn, food for carnivores. Some carnivores occupying the top trophic layer of the food web predate on both herbivores and carnivores in lower layers. A complication to this model is the organisms which consume both producers and other consumers, namely the omnivores. The food chain ecosystem is powered ultimately by solar energy fixed by green plants, the primary producers. Energy is lost at each level through respiration (heat loss, excretion etc.) and because photosynthesis is not highly efficient at trapping solar radiation, only a small amount of the light is converted into plant biomass. The Woodland Layers A habitat may be described by its vegetation, its geology or its soil type. Associated with each habitat is usually a suite of plants, invertebrates, birds and mammals and perhaps also reptiles and amphibians. A woodland which contains some or all of these creatures must provide biologically appropriate habitat types. Habitats within a woodland exist variously within its trophic structure, the layers. The layers, for example, provide different feeding, nesting and roosting sites for birds and bats. The ground layer extends above and below the surface and is composed of many different types of habitats which support a great variety of species including springtails, mites and beetles. Mosses host beetles, spiders and snails. Leaf litter is an extensive food source for detritivores such as millipedes, woodlice, earwigs, moths and larvae, and these in turn attract carnivorous invertebrates such as spiders, harvestmen, pseudoscorpions, mites and centipedes for which they are prey. The soil of course contains worms and other invertebrates whose products are further reduced by the bacteria and fungi living in the roots systems. Above the ground layer is the herbage, or plant, layer. Here grow the flowers and grasses among dead timber, rocks and stones etc. During spring, summer and autumn plants sprout, grow and die and some invertebrate species rely on specific plants and herbs in this layer as their sole food source. Many carnivorous invertebrates are dependent on this micro-climatic zone for its humidity as well as its hiding places and structures to build webs and traps, and opportunities to hunt and chase prey. This is the dead wood habitat. Dead wood is important for lower plants and fungi. This is the richest and most productive of layers and contains centipedes, beetles, snails, slugs, larvae, millipedes, flies, woodlice, moths, spiders, earwigs, springtails, harvestmen, pseudoscorpions, bugs, wasps etc. Dead timber is used by many beetles and flies for breeding and its sugar loaded sap as a food source for their larvae, with fungi colonising the timber as it is breaking down. At the upper heights of this layer most of the flowering plants, herbs and grasses occur and it is where many butterflies and moths lay eggs and so their larvae, and that of sawfly, are dependent on it for their food sources. Here also are many species of flies, bees, wasps, weevils, beetles, aphids, ladybirds, spiders and ants. The plant communities provide a structure which traps pockets of heat, plant material and air warmed by sunshine; a micro-climate which supports increased rates of reproduction. The next layer is the bush and scrub layer. These are the plants which grow higher with small trunks and twiggy, close set branches. They usually form thickets, flower and develop complete leaf cover during spring and summer, providing habitats for animals which live and feed openly or secretively by being nocturnal, or within the plant material away from predators. 3 The Virtual Woodland Teachers’ Notes Above the bush and scrub layer is the layer with fewest associated species, the mid or sub-canopy. It is the area with the fewest leaves to act as food but also, since much of the sunlight is shaded by the leafy canopy layer above it, the area of least available energy. It has relatively stable humidity however, and is a preferred habitat for adult flies associated with feeding on flowers and dung, as well as predatory flies. The top layer, the upper canopy, is a rich area for invertebrates, particularly insects. It provides a great amount of food material for herbivorous insects and their larvae nectar for adult flies, beetles, wasps, moths and bees. The leafy canopy receives, and reflects, the highest levels of solar energy causing very high temperatures to exist. Canopy cover is a determinant in terms of fungi and lichens at ground and shrub levels and certain beetles are influenced by latitude and canopy cover. Effects of Climate Change Perhaps the main concern with climate change is linked to rising carbon levels due to fossil fuel combustion and to deforestation, resulting in increased temperature (global warming) and increased precipitation (such as rainfall). Habitat types or constituent species are likely to be affected by changes to climatic conditions. Increasing concentrations of atmospheric carbon dioxide enhances the growth of plants. Increased surface area of leaves allows more photosynthesis, but can also affect transpiration, the way the plant regulates water loss into the atmosphere. Leaves let carbon dioxide in and water out. They keep the air humid and contribute to rainfall, whilst reducing water run-off from the soil. More rapid growth means that plants will incorporate greater levels of carbon relative to nitrogen in their cell structures. This could lead to two adverse effects. Firstly, it could affect the nutritional quality of forage for herbivores. Secondly, it could stimulate growth of shoots relative to roots and increase the risk of instability. Mean temperature changes may cause some plant and animal species to shift northward or to higher altitudes. Since some species move more rapidly than others, the combination of species regarded as typical of certain habitat will change. Changes in the dominant species will affect the type and number of other species. If the dominant tree species in a woodland changes, then the ground flora may be affected by a different humus cover due to changes in light intensity. This, in turn, may lead to adverse numbers in terms of resident and invasive biological species. Perhaps the most significant concern is how that will affect invertebrate populations and communities occurring in those sites. In the woodland biosphere the components in the soil strongly determine colonising vegetation. Some of the effects of climate change will be indirect and influenced by two factors: stressed trees are susceptible to pests and disease, and most insect pests benefit from increased summer activity and decreased winter adversity. Some insect pests and pathogens may become more prevalent and extend their range northward and/or expand uphill. Most damage to forests is caused by extreme events. A higher incidence of storms may make a woodland more vulnerable to wind damage. Heavy rain combined with low temperatures causes problems for insects, birds and bats. In extended summers hit by heat-waves, droughts and wildfires will pose an increased threat.