* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download `RING AROUND A ROSIE` A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE BUBONIC

Survey

Document related concepts

Behçet's disease wikipedia , lookup

Kawasaki disease wikipedia , lookup

Sociality and disease transmission wikipedia , lookup

Transmission (medicine) wikipedia , lookup

Hospital-acquired infection wikipedia , lookup

Schistosomiasis wikipedia , lookup

Infection control wikipedia , lookup

African trypanosomiasis wikipedia , lookup

Childhood immunizations in the United States wikipedia , lookup

Germ theory of disease wikipedia , lookup

Transcript

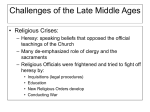

ZZZ ‘RING AROUND A ROSIE’ A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE BUBONIC PLAGUE by Gail Berry “Ring-a-ring of roses / A pocketful of posies / At-choo at-choo! / We all fall down!” This charming rhyme still recited by children today dates back to the London Plague of 1665. The “ring of roses” describes the red buboes around the neck of an infected person (swollen lymph nodes); ”posies” refers to the herbs or flowers that people carried in their pockets to breathe hoping it would protect them from the disease; “at-choo” refers to a sneeze which was the sign of coming illness. “All fall down” describes the suddenness of death from what is today called “Black Death” or Bubonic Plague. The plague (Latin: a blow) or Black Death has been mentioned in historical accounts for centuries and can be traced over 2300 years ago to China. Imagine waking up one morning and hearing your brother or sister complain of a headache. By the end of the week, you are the only one in your family left alive. Even worse, you are the only one of a very few in your town left alive. This story repeated itself over and over again throughout medieval Europe as the Black Death—the bubonic plaque—swept the continent from 1347 to 1352. Named for the black swellings called “buboes” that covered the bodies of the afflicted, the plaque wiped out one-third to onehalf of Europe’s population and ushered in massive religious, economic, and social changes as the remaining population adjusted to the shock of losing an estimated 25 million people in a period of just five years. The true scourge, however, struck Europe in the mid-1300s and killed thirty-five percent of the population, about 43 million people. This huge number of deaths caused the median age life-span to plummet from thirty five years to just twenty years. The bacteria which we now know as Yersinia Pestis, was carried from China across the East in to Europe by Mongolian merchants. It was originally brought to ports by rats infected with fleas which would infest wool, silk, linen and boxes of goods being transported by ship to ports and cities throughout Europe. The plague spread through every level of society and could not be avoided. It would strike a city, driving terrified ZZZ residents to escape on boats to safe harbors thereby unknowingly spreading the disease further and further. The fear of the disease and confusion is said to have increased a level of medical beliefs, one of which was to carry flowers or herbs to avoid the stench of the illness and perhaps the “evil” that afflicted victims. It was difficult to study the disease as it was highly infectious and death usually came (mercifully) within four days of the first signs of the illness. It is believed that priests and monks unwittingly spread the infection as they would go from home to home to perform last rites. It is also estimated that 90% of priests and 75% of physicians died during the epidemic because of their willingness to minister and serve during the worst of the plague. Eventually running its course in the 14th century, the plague reappeared in London in 1665, and Marseille in 1680. While many died, it did not reach the same level of infection and death as the scourge of the 1300s did. It wasn’t until 1894 that the disease was conclusively connected to rats and the fleas burrowed in their fur. Mass graves have been found from the European and London epidemics (1347 and 1660s) and the remains were studied in the 1990s. The bacterial genomes show that there is very little difference of the infectious strain found in those human remains when compared to the contemporary Yersinia Pepstis bacteria that carries the plague. Is the plague bacteria something to worry about in contemporary times? Probably not, although there are cases reported from time to time, most recently in Oregon. A man cut his finger as he tried to dislodge a dead mouse stuck in the throat of his cat. He quickly came down with symptoms of severe flu and was diagnosed within days to have the Bubonic Plague. Because of modern day medicines, however, he has been treated–as are all cases that may show up around the world. Streptomycin and gentamycin are the antibiotics of choice for this horrendous illness, which has plagued the world for over two thousand years. Attributed Sources: Medicine in Art, Georgio Bordon, J Paul Getty Trust, 2010 “Oregon Man Recovering from Bubonic Plague”, MSNBC, 18 July 2012