* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download arXiv:0905.2946v1 [cond-mat.str-el] 18 May 2009

Path integral formulation wikipedia , lookup

Quantum computing wikipedia , lookup

Relativistic quantum mechanics wikipedia , lookup

Quantum decoherence wikipedia , lookup

Matter wave wikipedia , lookup

History of quantum field theory wikipedia , lookup

Aharonov–Bohm effect wikipedia , lookup

Orchestrated objective reduction wikipedia , lookup

Molecular Hamiltonian wikipedia , lookup

EPR paradox wikipedia , lookup

Renormalization group wikipedia , lookup

Topological quantum field theory wikipedia , lookup

Quantum machine learning wikipedia , lookup

Particle in a box wikipedia , lookup

Interpretations of quantum mechanics wikipedia , lookup

Hydrogen atom wikipedia , lookup

Quantum key distribution wikipedia , lookup

Quantum group wikipedia , lookup

Quantum teleportation wikipedia , lookup

Coherent states wikipedia , lookup

Quantum state wikipedia , lookup

Hidden variable theory wikipedia , lookup

Theoretical and experimental justification for the Schrödinger equation wikipedia , lookup

Symmetry in quantum mechanics wikipedia , lookup

Canonical quantization wikipedia , lookup

Topological order in paired states of fermions in two-dimensions with breaking of

parity and time-reversal symmetries

Noah Bray-Ali,1 Letian Ding,1 and Stephan Haas1

arXiv:0905.2946v1 [cond-mat.str-el] 18 May 2009

1

Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 90089

(Dated: May 18, 2009)

We numerically evaluate the entanglement spectrum (singular value decomposition of the wavefunction) of paired states of fermions in two dimensions that break parity and time-reversal symmetries, focusing on the spin-polarized px + ipy case. The entanglement spectrum of the weak-pairing

(BCS) phase contains a Majorana zero mode, indicating non-Abelian topological order. In contrast,

for the strong-pairing (BEC) phase, we find no such mode, suggesting Abelian topological order.

In both phases, the leading correction to the area law behavior of the entanglement entropy has a

geometric origin, while at the quantum phase transition, our large-scale numerical results indicate a

universal, logarithmic correction to the area law. We find that the entanglement spectrum detects

topological order in the ground-state wavefunction more robustly than the entanglement entropy

for states of paired fermions.

PACS numbers: 74.20.Rp;03.67.Pp;71.10.Pm;74.90.+n

Introduction.– Two-dimensional fermion systems with

pairing that breaks parity and time-reversal symmetries come in a variety of forms including quantum hall

fluids,[1, 2] superfluids,[3] superconductors,[4] and condensates of cold atoms near a Feshbach resonance.[5, 6]

For spin-polarized fermions, the simplest pairing order

parameter that breaks these symmetries, ∆p ∝ px + ipy ,

depends on the relative momentum p of the fermions

in a pair. For momentum independent, s-wave pairing, a smooth cross-over occurs from weak-pairing (BCS)

to strong-pairing (BEC). In the px + ipy case, the two

phases have different topological order and are separated by a quantum phase transition.[7] Recent proposals for fault-tolerant quantum computation using twodimensional fermion systems with px + ipy pairing require the system to be in the weak-pairing phase.[8] This

motivates us to investigate the topological order of the

weak-pairing and strong-pairing phases using ideas from

quantum information theory.

The entanglement spectrum[9] and the entanglement

entropy[10] contain information about the universal

properties of a quantum state. We define them by dividing the system into a block A with feature size L and

an environment B, and then performing a Schmidt decomposition,

X 1

e− 2 ξi |ψiA i ⊗ |ψiB i.

(1)

|ψi =

i

Here, the orthonormal sets of states {|ψiA i}, {|ψiB i} span

A and B. The entanglement

P spectrum {ξi } gives the entanglement entropy S = i ξi e−ξi .

Recently, Li and Haldane gave numerical evidence that

the entanglement spectrum probes topologically protected edge excitations.[9] The result can be understood

by considering a physical process that cuts into two parts,

A and B, a system with bulk excitation gap E0 and gapless edge excitation spectrum. If we perform the cut at

some rate, Γ ≪ E0 , adiabatic with respect to the bulk excitation gap, then the possible outcomes in region A are

the Schmidt eigenvectors {|ψiA i}, with the entanglement

spectrum {ξi } measuring the likelihood of each possibility. Now, even if one proceeds slowly with respect to the

gap E0 , avoiding bulk excitations, the gapless edge modes

are still likely to be excited. The entanglement spectrum

detects these topologically protected edge modes, providing insight into the form of topological order in the

bulk.

In this Letter, we report the first large-scale numerical calculations of the entanglement entropy and spectrum of two-dimensional fermion systems with px + ipy

pairing. We find that the entanglement entropy exhibits

universal critical behavior in the vicinity of the quantum phase transition separating weak-pairing and strongpairing. Further, we find that the entanglement spectrum

qualitatively distinguishes the topological order occurring in the two phases. In particular, we find that the

low-lying spectrum in the weak-pairing phase contains

a chiral, gapless fermion excitation. The weak-pairing

phase is known to have a chiral, gapless Majorana edge

mode.[7] This mode is intimately related to the Majorana

zero mode that appears in vortex cores and gives vortices

non-Abelian statistics.[7, 11]

We reduce the problem of evaluating the entanglement

spectrum and entanglement entropy to diagonalizing a

quadratic entanglement Hamiltonian.[12] This approach

does not include fluctuations of the pairing order parameter, and, hence, we do not expect to observe a universal,

topological term in the entanglement entropy[13, 14] in

either the weak-pairing or strong-pairing phase,[15] despite the fact that both phases have non-trivial quantum

dimension D = 2. Instead, we find that the entanglement spectrum detects topological order in the groundstate wavefunction more robustly than the entanglement

entropy for states of paired fermions.

2

Pairing

Hamiltonian.–

The

following

BCS

Hamiltonian[16] serves as a minimal model for a

single band of spin-polarized fermions with px + ipy

pairing on a square lattice:

X

X c†r cr

c†r cr′ + c†r′ cr + 2λ

H=− t

hr,r ′ i

80

Weak-Pairing

0

1.0

=1.0

0.5

=3.0

40

=2.5

=2.0

0.0

0

1

2

3

4

=1.5

hr,r ′ i

=1.0

′

We consider only nearest-neighbor hr, r i hopping t and

pairing γr,r′ interactions. The hopping strength t and

coupling λ are taken to be real and positive, without

loss of generality. The pairing interaction γr,r′ breaks

both time-reversal and parity symmetries: γr,r+x̂ =

−γr,r−x̂ = iγr,r+ŷ = −iγr,r−ŷ = iγ. Here, γ is real and

x̂, ŷ are the primitive translation vectors of the square

lattice. We use periodic boundary conditions in our numerical calculations.

The pairing Hamiltonian (2) is quadratic and can be

solved exactly using a Bogoliubov transformation,[17]

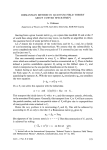

yielding the phase diagram shown in the inset of Fig. 1.[7]

The critical line at λc = 2t, separates the weak-pairing

(BCS) phase from the strong-pairing (BEC) phase.

Both phases have a spectral gap E0 = t|λ − λc | to

bulk excitations show in the inset of Fig. 1 and determined by minimizing

the Bogoliubov quasi-particle

q

2

ξp2 + |∆p | . The pairing order padispersion:Ep =

rameter ∆p = 2γ(sin px + i sin py ) transforms under the

symmetries of the square lattice in the same way as an

ℓ = 1, ℓz = 1 spherical harmonic. At small p, we expand ∆p ∝ px + ipy , and see the px + ipy pairing explicitly. Similarly, at small p, the single-particle kinetic

energy ξp = −2t(cos px + cos py ) + 2λ, takes the form

ξp = p2 /2m∗ − µ, with effective mass m∗ = 1/2t and

µ = 4t − 2λ. The weak-pairing phase λ < λc corresponds

to µ > 0, while strong-pairing λ > λc corresponds to

µ < 0.[7]

Entanglement Hamiltonian.–The two-point correlation

functions provide a complete description of the ground

state of the quadratic Hamiltonian (2), and allow an efficient numerical evaluation of the Schmidt decomposition

(1).[12] In fact, the Schmidt decomposition of the pairing Hamiltonian ground-state reduces to diagonalizing

the following entanglement Hamiltonian He which acts

on the sites of the block A:

X

X

He =

Fr,r′ c†r c†r′ + h.c. .(3)

Cr,r′ c†r cr′ + h.c. +

r,r ′

(BEC)

E

60

S

(2)

Strong-Pairing

(BCS)

1.5

r

X ∗

,

γr,r′ c†r c†r′ + γr,r

−

′ cr ′ cr

2.0

r,r ′

Here, in contrast to (2), the hopping parameters Cr,r′ =

hc†r cr′ i and pairing parametersFr,r′ = hcr cr′ i extend

beyond nearest-neighbors and are given by the twopoint correlation functions in the ground state of the

pairing Hamiltonian (2). The entanglement Hamiltonian is quadratic, and can be exactly solved by numerically performing a Bogoliubov transformation to the

20

0

10

20

L

30

40

50

FIG. 1: (Color online) Entanglement entropy S between a

square of side length L and its environment as a function

of λ at fixed pairing strength γ = 1.0. (Inset) The zerotemperature phase diagram of two-dimensional fermions with

px + ipy pairing and plot of the bulk spectral gap E0 . The

phase boundary between weak-pairing and strong-pairing is

the vertical γ-independent line at λc = 2t. The spectral

gap vanishes at the critical coupling and grows linearly with

|λ − λc |. Data points indicate the parameters chosen in our

numerical calculations (t=1).

quasi-particle operators αn , for n = ±1, ±2, . . . ± NA ,

where, NA is the number of sites in the block A.[17] In

terms of the quasi-particles,

P the entanglement Hamiltonian has the form He = n>0 f (ǫn )(α†n αn + 21 ), where,

f (ǫ) = (eǫ + 1)−1 is the Fermi function and the quasiparticle eigenvalues {ǫn } generate the entanglement spectrum. In P

particular, the entanglement entropy is given

by S = − n f (ǫn ) log f (ǫn ).

Results.– Fig. 1 shows the entanglement entropy S as a

function of the block size L. We consider various coupling

strengths λ that sweep through the quantum phase transition, as shown in the inset. The entropy grows linearly

with L for this two-dimensional system, consistent with

an area law SL = aL + . . . . Fermion systems generically

violate the area law if they have a Fermi surface of gapless excitations.[18, 19, 20] Remarkably, we observe the

area law even at the quantum phase transition where the

bulk excitation gap vanishes at a single point in momentum space. Other two-dimensional fermion systems with

point nodes obey the area law.[20, 21] We present the

first numerical evidence for area law behavior in a gapless fermion system that breaks parity and time-reversal

symmetries. In the gapped phases, rigorous theoretical

arguments[22] suggest that an area law must hold. The

results in Fig. 1 are the first large-scale numerical test of

this argument for fermion systems that break parity and

time-reversal symmetries.

Using these large-scale numerical results, we are able

to extract the leading correction to the area law ∆S =

3

3

1.5

=1.0

=3.0

(a)

A

=2.5

=2.0

1.0

=1.0

S

S

1

0.5

0

0.0

10

20

30

10

40 50

L

20

30

40

50

L

=2.04

(c)

(d)

=2.08

=2.16

3

4

4

2

2

6

=1.5

cr

=1.0

6

=2.0

2

=1.5

sq

A

=2.5

6

(b)

=3.0

Block Enegy Spectrum

=1.0

4

=1.5

=1.0

2

=1.0

cr

cr

=2.5

S / S

S / S

=3.0

=2.00

2

=2.01

=2.02

10

20

30

L

40

50

0

0

sq

sq

3

10

20

30

40

50

L

FIG. 2: (Color online) Leading correction term ∆S to the

area law for a square (a) and cross-shaped (b) partition as a

function of block size L. (Inset) geometry of the partitions.

Notice the linear scale for ∆S and the logarithmic scale for L

in both (a) and (b). Solid lines are guides to the eye. Ratio

∆cr /∆sq of the leading correction terms from (a) and (b)

as function of block size L: (c) within the weak-pairing and

strong-pairing phases; (d) approaching the quantum phase

transition from the strong-pairing regime.

−3(S − aL). We plot the size dependence of the leading

correction ∆Ssq for the square shaped partition shown in

Fig. 2(a) and for the cross-shaped partition ∆Scr shown

in Fig. 2(b). For both geometries, the leading correction grows at the critical point with L, without sign of

saturation. By contrast, in the weak-pairing and strongpairing phases, the leading correction saturates to an L

independent value as L → ∞.

We interpret the growth at the critical point as a logarithmic divergence, of the form S = aL − b log L + . . . .

The constant of the logarithmic growth b clearly depends

on the partition geometry, as can be seen by comparing

the data for the square and cross in Fig. 2(a) and (b).

However, for a given geometry, for example the square,

we observe approximately the same coefficient b ≈ .13

at all points along the phase boundary between weakpairing and strong-pairing (data not shown). We emphasize that two-dimensional fermion systems with px + ipy

pairing obey the area law: the logarithmic divergence

appears as the leading, additive correction. Universal,

logarithmic corrections to the area law occur at other

two-dimensional quantum phase transitions.[23, 24] Nonuniversal, logarithmic corrections to the area law arise

throughout the nodal phase of two-dimensional fermion

systems with time-reversal invariant pairing.[25]

The leading correction to the area law shown in

Fig. 2(a) and 2(b) clearly depends on the geometry of

the partition. In Fig. 2(c) and (d), we analyze this de-

0

/2

(a)

3 /2

=2.0

0

/2

(b)

3 /2

(c)

=3.0

0

/2

3 /2

Angular Momentum

Angular Momentum

Angular Momentum

FIG. 3: (Color online) Low-lying quasi-particle entanglement

spectrum {ǫn } (a) in the weak-pairing phase, (b) at the quantum phase transition, and (c) in the strong-pairing phase with

fixed pairing strength γ = 1.0. We divide the spectrum into

four sectors based on the discrete angular momentum of the

quasi-particle wavefunction.

pendence by plotting the ratio of the leading correction

∆Scr /∆Ssq for the two partition geometries show in the

insets of Fig. 2(a) and (b). Notice that the cross has

twelve corners, while the square has four corners. In

both strong-pairing and weak-pairing phases (Fig. 2c),

the ratio ∆Scr /∆Ssq → 3 approaches a constant in the

limit of large block size L. Remarkably, the ratio of the

leading correction term to the area law equals the ratio of the number of corners of the two partitions. We

have examined other geometries and find the behavior

∆S = cnc , where, nc is the number of corners and c is

a positive coefficient. A similar corner effect has been

observed analytically in a wide class of topologically ordered phases.[26]

As we approach the critical point from the strongpairing phase, Fig. 2(d), the ratio takes longer to saturate as a function of L. At the critical point, λc = 2.0,

the data appear to saturate at a value that is not given

simply by the ratio of corners. This should be contrasted

with the geometry dependence of the logarithmic correction to the area law observed for two-dimensional conformal quantum critical points.[23] In that case, each corner with angle θ contributes a correction to the area law

2

cθ

∆S = 24π

(1 − πθ2 ) log L, where, c is the central charge of

the conformal field theory describing equal-time, spatial

correlations.[23] Conformal quantum critical points have

dynamical expondent z = 2, and are in a different universality class than the quantum phase transition in px + ipy

paired fermions with dynamical exponent z = 1. We do

not expect, and indeed do not numerically observe, the

geometric dependence predicted for conformal quantum

critical points.

4

Minimum Block Energy

10

=1.0

=1.25

1

=1.5

=1.75

=1.92

=1.96

=1.98

=1.99

=2.0

=2.25

0.1

=2.5

=2.75

=3.0

0.01

0.1

1

1/L

FIG. 4: (Color online) Finite-size scaling of minimimum block

energy level ǫ0 plotted on a log-log scale at fixed pairing amplitude γ = 1.0. In the weak-pairing phase λ < 2.0, the

dashed lines are best fits to the scaling form ǫ0 ∼ 1/L.

To detect topological order, we turn to the entanglement spectrum shown in Fig. 3. We label the quasiparticle eigenvalues {ǫn } by discrete angular momenta

ℓ = 0, π2 , π, 3π

2 , describing the transformation properties

under the point group of the square lattice. Under a rotation by π2 , the quasi-particle wavefunction acquires phase

factors eiℓ = 1, +i, −1, −i. The low-lying spectrum contains a dispersive mode whose block energy increases with

angular momentum in the weak-pairing phase Fig 3(a)

and at the quantum phase transition, Fig 3(b). We

contrast this with the featureless low-lying spectrum in

the strong-pairing phase, Fig. 3(c). Switching to p − ip

pairing (data not shown), the dispersive mode in the

weak-pairing phase and at the quantum phase transition

switches direction: its block energy increases with decreasing angular momentum. We interpret this low-lying

feature as a chiral excitation mode, since it has a velocity ∆ǫ/∆ℓ that reverses sign under time-reversal. In the

weak-pairing phase, the minimum block energy ǫ0 ≈ 0

appears to be gapless in Fig. 3(a). In contrast, the spectrum in the strong-pairing phase appears to be gapped.

We show in Fig. 4, the finite-size scaling of the minimimum block energy level ǫ0 plotted on a log-log scale at

fixed pairing amplitude γ = 1.0. In the strong-pairing

phase, the minimum block energy ǫ0 tends to a constant as L → ∞. By contrast, in the weak-pairing

phase λ < 2.0, the minimum block energy drops to zero

ǫ0 ∼ 1/L, indicating the presence of a zero mode in the

entanglement spectrum in the limit L → ∞. At the

quantum phase transition, λc = 2, the finite-size scaling

of the minimum block energy is not constant, but de-

creases much more slowly than the scaling ǫ0 ∼ 1/L seen

in the weak-pairing phase.

Conclusion– In this Letter, we study topological order

in paired states of fermions with parity and time-reversal

symmetry breaking. Large-scale numerical calculations

of the entanglement spectrum and entanglement entropy

reveal universal behavior, including a divergent correction to the area law at the quantum phase transition

separating weak-pairing and strong-pairing phases. We

find evidence for a chiral, gapless Majorana fermion excitation in the entanglement spectrum of the weak-pairing

phase, and contrast this with the gapped spectrum in the

strong-pairing phase. A variety of topological phases can

be described by a pairing Hamiltonian that neglects order parameter fluctuations. We suggest that large-scale

numerical calculations of the entanglement spectrum are

a robust way to detect topological order in the groundstate wavefunction of such phases.

NBA acknowledges the 2008 Boulder Summer School

and NCTS for their hospitality during the completion of

this work. Computational facilities have been generously

provided by HPCC at USC. We are grateful for fruitful

discussions with A. Feguin, M.P.A. Fisher, A. Kitaev,

F.D.M Haldane, Z. Nussinov, K. Raman, and P. Zanardi.

[1] R. L. Willett, J. P. Eisenstein, D. C. Tsui, A. C. Gossard,

and J. H. English, Phys. Rev. Lett. 59, 1776 (1987).

[2] G. Moore and N. Read, Nucl. Phys. B 360, 362 (1991).

[3] D. D. Osheroff, R. C. Richardson, and D. M. Lee, Phys.

Rev. Lett. 28, 885 (1972).

[4] T. M. Rice and M. Sigrist, J. Phys. Condens. Matter 7,

L643 (1995).

[5] V. Gurarie, L. Radzihovsky, and A. V. Andreev, Phys.

Rev. Lett. 94, 230403 (2005).

[6] C.-H. Cheng and S.-K. Yip, Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 070404

(2005).

[7] N. Read and D. Green, Phys. Rev. B 61, 10267 (2000).

[8] S. Tewari, S. Das Sarma, C. Nayak, C. Zhang, and

P. Zoller, Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 010506 (2007).

[9] H. Li and F. D. M. Haldane, Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 010504

(2008).

[10] M. Nielsen and I. Chuang, Quantum Computation and

Quantum Information (Cambridge, 2000), p. 510.

[11] D. A. Ivanov, Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 268 (2001).

[12] M.-C. Chung and I. Peschel, Phys. Rev. B 64, 064412

(2001).

[13] A. Kitaev and J. Preskill, Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 110404

(2006).

[14] M. Levin and X.-G. Wen, Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 110405

(2006).

[15] Z. Nussinov and G. Ortiz, Ann. Phys. (N.Y.) 324, 977

(2009).

[16] J. Bardeen, L. N. Cooper, and J. R. Schrieffer, Phys.

Rev. 108, 1175 (1957).

[17] J.-P. Blaizot and G. Ripka, Quantum Theory of FiniteSystems (MIT Press, 1986), pp. 34–38, 101–103.

[18] M. M. Wolf, Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 010404 (2006).

5

[19] D. Gioev and I. Klich, Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 100503

(2006).

[20] W. Li, L. Ding, R. Yu, T. Roscilde, and S. Haas, Phys.

Rev. B 74, 073103 (2006).

[21] T.Barthel, M. Chung, and U. Schollwock, Phys. Rev. A

74, 022329 (2006).

[22] M. M. Wolf, F. Verstraete, M. B. Hastings, and J. I.

Cirac, Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 070502 (2008).

[23] E. Fradkin and J. E. Moore, Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 050404

(2006).

[24] R. Yu, H. Saleur, and S. Haas, Phys. Rev. B 77, 140402

(2008).

[25] L. Ding, N. Bray-Ali, R. Yu, and S. Haas, Phys. Rev.

Lett. 100, 215701 (2008).

[26] S. Papanikolaou, K. S. Raman, and E. Fradkin, Phys.

Rev. B 76, 224421 (2007).