* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download A Simplified Method of Teaching the Position of Object Pronouns in

American Sign Language grammar wikipedia , lookup

Sanskrit grammar wikipedia , lookup

Macedonian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Swedish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Ojibwe grammar wikipedia , lookup

Lithuanian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Old English grammar wikipedia , lookup

Udmurt grammar wikipedia , lookup

Scottish Gaelic grammar wikipedia , lookup

Malay grammar wikipedia , lookup

Navajo grammar wikipedia , lookup

Lexical semantics wikipedia , lookup

Old Irish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Modern Hebrew grammar wikipedia , lookup

Kannada grammar wikipedia , lookup

English clause syntax wikipedia , lookup

Ancient Greek grammar wikipedia , lookup

Yiddish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Georgian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Hungarian verbs wikipedia , lookup

Modern Greek grammar wikipedia , lookup

Chinese grammar wikipedia , lookup

Polish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Spanish verbs wikipedia , lookup

Portuguese grammar wikipedia , lookup

Icelandic grammar wikipedia , lookup

Turkish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Serbo-Croatian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Latin syntax wikipedia , lookup

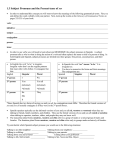

A Simplified Method of Teaching the Position of Object Pronouns in Spanish Author(s): Ronald J. Quirk Reviewed work(s): Source: Hispania, Vol. 85, No. 4 (Dec., 2002), pp. 902-906 Published by: American Association of Teachers of Spanish and Portuguese Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4141258 . Accessed: 23/01/2012 12:48 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. American Association of Teachers of Spanish and Portuguese is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Hispania. http://www.jstor.org A Simplified Method of Teaching the Position of Object Pronouns in Spanish Ronald J. Quirk Quinnipiac University Abstract: The placement of direct, indirect, and reflexive object pronouns is often presented disjointedly in textbooks. We offer a succinct, easily-learnedpair of mnemonic devices that have universalapplicabilityfor the position of object pronounsin Spanishsentences. The acronymIGA indicatesthat these pronounsfollow and are appendedto infinitives,gerunds,and affirmativecommands;otherwise,the pronounsdirectlyprecede the verb.In sentences where two positions are allowed, applicationof the IGA rule will reveal both possibilities. The acronym RID prescribesthe sequentialorderof two object pronounsto be always reflexive, indirect,and direct,whetherthey precede or follow the verb. Additionally,the use of accent markswhen pronounsare appendedto verbs and the substitutionof se for le or les are simplified in a concise didactic system. Key Words: Spanish object pronouns,word order in Spanish Many good collegetextbooksfor elementarySpanishintroducedirect,indirect, andreflexive objectpronounsover many pages and several lessons, with other topics intervening.A' treatsreflexives in Chapter4, indirectobjectpronounsin Chapter6, and direct object pronounsin Chapter7. The "nosotros"commandsand the use of pronounswith them are left until Chapter15. B likewise separatesobject pronounsinto Chapters4, 6, and 7. C begins with direct object pronounsin Lecci6n 4, adds the indirect objects and reflexives in Lecci6n 5, and concludes with first-personplural commandsin Lecci6n 10. D spreadsthe objectpronounsover Chapters7 and 8, and explainsthe combined use of two pronounsin Chapter11. In intermediatetexts the spacingof materialon objectpronounsis similar.E gives direct object and indirectobjectpronounsin Lesson 2, butreflexives areheld until Lesson 4. Sixtyfour pages of grammarand exercises come between where object pronounsare first mentioned and a final summarytable of them on page 100. F begins with reflexives in Capitulo 2, continues with "nosotros"commands in Capitulo4, and treatsdirect and indirectobject pronounsin Capitulo5. G includes both directand indirectobjectpronounsand theircombined usage in Lecci6n 3 but leaves reflexives for Lecci6n 4. H teaches the various object pronounsin Chapters3 and 6. I, in contrast,includes all the object pronounsin its Unit 12. Even in some books of advanced Spanish grammar,this topic is presented in an analogous way. In J the forms, usage, and position of object pronounsreceive intermittent attentionfrompage 53 to page 356. K, on the otherhand,neatlypresentsall the objectpronouns within two pages (411-12). From these representativetexts the general pattern is clear: in Spanish grammar textbooksthe usualtreatmentof the objectpronounsis gradualandextended.Thereis sound reason for this separationof material,especially in introductorytextbooks.Authorswantto minimize students'confusion of the variousobjectpronounsby teachingthem individually, in isolationfromone another.But this diffuse presentationalso leads to multipleinstructions on the placement of the object pronouns.In A directionsfor placementoccur on pages 93, 105, 157, 181, 335, and 373. In E this topic is first addressedon page 37 and not concluded until page 195. G teaches the three kinds of pronouns in Lessons 3 and 4 but extends Quirk,RonaldJ. "A Simplified Method of Teachingthe Position of Object Pronounsin Spanish" Hispania 85.4 (2002): 902-906 Object Pronoun Position in Spanish 903 instructionon theirplacementover Lessons 3, 4, and6. Even textbooksthataremoreconcise in dealingwith the locationof the variousobjectpronounsdo not succinctlyformulateeasilymemorized guides for placement of them. C, for example, explains the placing of a single objectpronounon one page (143) andthe sequence of indirectanddirect-objectpronounson anotherpage (204), but does not offer students a summaryformula as a learning aid. H furnishesan orderlyandcompactchartof the positions of directandindirectobjectpronouns (66), but this intermediate-levelreference work also lacks an integrating formula for placement.The advanced-levelK recapitulatesthe position of these pronounsin threebriefly statedrules (412), but again this is without a succinct mnemonic aid. Such spread-out presentations, or even a more concentratedbut still inconclusive treatment,should be complementedby a clarifying and systematizingpedagogy that draws togetherand reiteratesthe basic rules of placement in a concise didacticform. In reality, the placementof the Spanishobjectpronounsis quite simple-it is simple to summarize,simple to teach, and simple to learn. First,let us define the issue. The personalobject pronounsarethe directobject, indirect object,andreflexive particlesthatreplacenouns (andnounmodifiers).2The objectpronouns all operatein the sameway with regardto place.3They are"clitics,"thatis, elementsthatmust be used with anotherword;in this case, with a verb. The grammaticalandpedagogical issue is when these entities are "proclitics"(i.e., come before the verb) and when they are "enclitics"(i.e., come afterthe verb). In sentencesthatcontainone objectpronoun,a simple acronymdefines placementof the pronoun. The letters IGA indicate that object pronouns follow infinitives, gerunds, and affirmativecommandsbutprecedeall otherverb forms.4This rule succinctly summarizesthe range of possibilities that can be encountered;it is valid for declarative,interrogative,and imperativesentences, and, indeed, it pertainsto all persons of the imperative:Ud., Uds., tzi, vosotros, and nosotros. In our choice of the term "gerund"for the form of the Spanishverb with the invariable ending -ndo, we follow the practiceof Holton (55), Jarvis(8), Rosso-O'Laughlin(139) and othersforthe pragmaticreasonthatstudentscan easily equatethe word"gerund,"which ends in -nd, with the Spanish form that ends in -ndo (e.g., hablando, comiendo, viviendo).5 Textbooks written in Spanish, such as Btrbara Mujica's advanced grammarEl pr6ximo paso, also label this a gerund:"el gerundioes la forma que terminaen -ndo. En ingles, esta formaterminaen -ing" (16). To begin an illustrationof the IGA rule,we can substitute(or add)pronounsin the proper place in the following sentences. Martaescribe una carta. Martaescribe a su hermana. Martaescribe una nota. > > > Martala escribe. (direct object) Martale escribe. (indirectobject) Parano olvidar, Martase escribe una nota. (reflexive) In all these cases the object pronoun,whetherit is a direct,indirect,or reflexive object, goes before the verb because the verb is not an I (infinitive), not a G (gerund),and not an A (affirmativecommand).These pronounsfunction as proclitics, and so they must be located immediatelybeforethe verb.Thusif oursentencewere negative(Martano escribeuna carta), the sentence with the pronoun would be "Martano la escribe," for nothing may intrude between the procliticpronounand the verb. The first model sentence above can be slightly expandedto "Martaquiere escribiruna carta."If the directobjectpronounla is substitutedfor una carta now, the applicationof the IGA rule will rendertwo answers. One may focus on the infinitive escribir and arrive at "Martaquiereescribirla."On the otherhand,the verb quiere is not an I (infinitive), not a G (gerund),andnot an A (affirmativecommand),so we can also say "Martala quiereescribir."6 The rule will not suggest any otherposition for la (such as between the two verbs), and no 904 Hispania 85 December 2002 otherposition is grammaticallyallowed. This is the greatadvantageof the IGA rule: when two positions for the object pronoun are possible, it will provide both options. The same possibility of two locations for the pronounoccurs when a gerund and an auxiliaryverb are involved. If we alterthe original sentenceto "Martaesti escribiendouna carta"and again substitutela for una carta, the result will be "Martaesta escribiendola" becauseescribiendois a gerund;butwe can also say "Martala estaiescribiendo"becauseest6 is not an I, a G, or an A. No otherposition for the pronounwill be called for by the IGA rule. Once again, this applicationof this rule will point out no fewer, and no more, than all the grammaticallyallowable positions for the object pronoun. With an affirmativecommand, only one place is possible for the pronoun-after the verb: escribela (tu), escribala (Ud.), escribanla (Uds.), escribidla (vosotros), and escribdmosla (nosotros).7 The direct object pronounla has been employed in most of our illustrationof the IGA rule, but everythingthat has been stated regardingword orderholds true for all the direct, indirect,and reflexive pronouns. The use of accentmarkswhen a pronounis appendedto the end of a verb is basedon the principle of maintainingthe original accentuationpatternof the verb. The first step is to determinewhere the stress was on the verb before a pronounwas added.All infinitives, of course,end in r, all gerundsend in o, andall affirmativecommandsend in a vowel (in singular commands)or the consonantsn (in pluralcommands),s (in first-personpluralcommands), or d(for vosotros).Exceptionsarethe irregulartziimperatives:haz,sal, etc. The accentuation for all these formsis the generalpatternfor Spanish:stressfalls on the next-to-lastsyllablefor wordsendingin anyvowel orn ors, andon the last syllableforwordsendingin any consonant except n or s. After the place of stress for the verb withoutthe pronounhas been determined by applyingthese principles,the pronounenclitic is attachedto the verb andthe same principles (word ending in vowel, n or s=stress on next-to-lastsyllable; word ending in another consonant=stresson last syllable) areappliedto the new verb-pronoununitto see if the stress would change. If the additionof the pronounwould move the stress on the verb, an accent markmust be writtenwherethe stresswas originally;if the place of stresswould not change, an accent markis not written. However, this underlying logic for the use of accent marks need not be thoroughly masteredin orderto use them accuratelywhen addingpronounsto verbs. In practicalterms, the explanationcan be thatan accent markis not placed on an infinitive when one pronoun is appended,but an accent markis always writtenon the last vowel before -ndo when one pronounis addedto a gerund.With affirmativecommands,an accentmarkwill be necessary on the last syllable of the verbunless the verbcontainsonly one syllable, likepon, ten, di, and so forth. With these one-syllable verbs, an accent markis not added. The placementof object pronounsis the same in sentences that involve two pronouns, the new issue thatmust be addressedis the orderof these pronounsamong themselves. but For the internalsequence of clitics, we introducea second mnemonic device. This is the acronymRID, which means thatthe orderof object pronounsis always: reflexive, indirect, direct. The same order is observed whether the pronouns follow or precede the verb. M. Kasey Hellerman has developed this guideline in iQud me cuenta? (26), a Spanish conversationtext that is now out of print. To illustratethe combinedapplicationof the IGA andRID rules, we can go backto our original sentence ("Martaescribe una carta") and add on another object to denote the recipientof the letter:"Martame escribeuna carta."Then, ifa pronounis substitutedfor una carta, there will be two pronouns,and the word orderwill be: "Martame la escribe."IGA demands locating the pronounsin front of escribe, and RID demandsthat the indirectme precede the direct la. Although RID fixes the relative position of all three types of pronouns-reflexive, Object Pronoun Position in Spanish 905 indirect,and direct-, they will not actuallybe used togetherin sequence;one or more of the three will always be absent. To explain this, Carlos Otero (169-70) has recourse to the terminology of Chomsky in generating a "surface exclusion rule" that precludes the possibility of se plus two other clitics. But the theoreticalbasis for the exclusion is not of importhere. Suffice it to say, for our pedagogical purposes,that all three elements of RID will never be presentconcurrently. Returningagain to our model sentences, if we take "Martava a escribir una carta," expandit to "Martava a escribirmeuna carta,"and substitutefor una carta, we end up with either "Martame la va a escribir"or "Martava a escribirmela." One usually cannotsplit the two pronounsup and put one before va and the otherafter escribir. It is possible to split them only in sentences like "nose permitebafiarseaqui"or "no lo dejes insultarnos"where one pronounclearly goes with one verb and the otherpronoun clearly goes with the otherverb. In the case of a gerund, "Martaesti escribiendome una carta" or "Martame esta escribiendo una carta"will become "Martaestd escribi6ndomela"or "Martame la esti escribiendo."The affirmativecommandsare "escribemela(td)," "escribamela(Ud.)," etc. Thuswe combineIGA to get the pronounsin the rightposition in the sentencewith RID to get the pronounsin the right orderamong themselves. With these two simple acronyms, IGA and RID, everythingfalls into place-literally, "falls into place." As we work with two pronouns,we note thatwhenever two thatbegin with the letterL come in a row, the firstpronounchanges to se. Thus, le la becomes se la; les los becomes se los, etc. Many textbooks explain that le and les become se before lo, la, los and las (C 205, F 140, andA 248), while otherbooks statethatif bothpronounsarethirdperson,the firstone changes to se (e.g., I 173). A simple, but accurate,way to teach this is to have studentsfocus on the first letter of the pronouns and to change the first pronoun to se (which is not a reflexive) when bothpronounsstartwith L. Puntos departida (267) employs this simplified explanation. And finally, accentmarkswill, logically, be more frequentlyneededto preserveoriginal verb stress when two pronounsare appendedto the verb. In fact, a written accent is always requiredif two pronounobjectsareaddedto the end of a verb. On infinitives,the accentmark will be on the letterbefore the r; on gerunds,it will be on the last letterbefore the ndo; and on affirmativecommands,it will be on the vowel of the next to last syllable in command forms of more thanone syllable, and on the vowel of the only syllable there is in commands of one syllable, for example, escribemela, digaselo, or dcnmelos. A fine point regarding accents is that when there are diphthongs,an accent markis not placed over a u or an i but ratherover the othervowel, as in mudstrameloor trciigaselos. The guidelineswe have explaineddescribethe position of the personalobjectpronouns in modernSpanish.However, studentswill not infrequentlyencounterdifferentword order as they read pre-contemporaryliterature.Most often this will be the placing of an object pronounaftera conjugatedverb or a past participle.One need look no furtherthan Chapter I of Don Quijote(1038) to find many such cases, amongthem, "perdiael pobre caballeroel juicio y desvelibase por entenderlas"and "Llen6selela fantasiade todo aquello que leia en los libros."As demonstratedby this second quotationfrom Cervantes, in older literature there was a particularaversion to beginning sentences with an object pronoun.Moreover, Otero mentionspostposition ("enclisis")as a stylistic practicethat "increasedsubstantially duringthe Romanticperiod"(172). Nor does this tendency end with Romanticism,as can easily be observedin the works ofRam6n del Valle-Inclkin:"limpi6sedos ligrimas," "rece16se,""quidrensedesde hace muchosafios"(73, 101, 102), etc. Actually, one finds suchword orderin worksof manyperiodsof Spanishliteraturein formulaicphraseslike "6raseunavez" or "6raseque se era"(= "once upon a time"). These examples from literature,while necessary to note, do not constitutethe norm in Spanish.The normis, in fact, an extremelyregular,even rigid, proclitic and enclitic modemrn 906 Hispania 85 December 2002 positioning system that is representedby the acronymsand guidelines we have explained. The IGA andRID rules,plus the simplified guide for replacingle and les by se and the summaries of written accent usage presented above, together constitute a concise, practical pedagogical method for instructorsto teach, and students to learn, the placement, order, alteration,and accentuationof verb-pronounclusters in Spanish. NOTES 'The textbooks examined for the presentstudy will be referredto by the lettersA, B, C, etc. Readerswith a need to know the identity of a particularreference may contact the author. 2The origin and historicaldevelopmentof these forms are extensively traced by Joel Rini in his monograph Motivesfor Linguistic Change in the Formation of the Spanish Object Pronouns. Rini indicates (2) that the placement of these pronounslies beyond the area of his study. 3Excludedfrom considerationare pronounobjects of a preposition,for they naturallyfollow the preposition. 41 wish to acknowledgewith gratitudethe late Agnes JenningsDraperas the source of the IGA mnemonicaid. 5Some books use the technically more accurate term "present participle" for this form. See Crystal's Encyclopedic Dictionary of Language and Languages (290-91) for the distinction between "gerund"and "participle." 6Dozier and Iguina(66-67) list the relatively infrequentinstances in which the object pronounmust follow the infinitive and may not precede the conjugatedverb. We suggest thattheirrule thatthe pronouncannotprecede the conjugatedverb "if the infinitive follows a preposition"should be amended, for such a sentence as lo voy a comprar is allowable. 7Constructionsof the type que lo haga Jorge are not to be considered affirmative commands but rather truncatedexpressions based on the patternquiero que lo haga Jorge that requiresa subjunctiveafter a verb of volition and a change of subject. WORKS CITED CervantesSaavedra,Miguel de. Obras completas. 24th ed. Ed. Angel Valbuena Prat.Madrid:Aguilar, 1965. Crystal, David. An Encyclopedic Dictionary of Language and Languages. Cambridge,MA: Blackwell, 1992. Dozier, Eleanor,and Zulma Iguina. Manual de gramatica. 2nded. Boston: Heinle & Heinle, 1999. Hellerman,M. Kasey. iQue me cuenta? New York: Macmillan, 1977. Holton, James S., Roger L. Hadlich, and Norma G6mez-Estrada.Spanish Grammarin Review. 3rd ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2001. Jarvis,Ana C., RaquelLebredo,and FranciscoMena-Ayll6n.iContinuemos!6th ed. New York:HoughtonMifflin, 1999. Knorre,Marty,Thalia Dorwick, Ana MariaPerez-Giron6s,William R. Glass, and HildebrandoVillarreal.Puntos de partida: An Invitation to Spanish. 6'"ed. Boston: McGrawHill, 2001. Mujica, Barbara.El prcximo paso: Gramaticaavanzada,Lecturas, Composici6n.FortWorth:Holt, Rinehartand Winston, 1996. Otero, Carlos. "The Development of the Clitics in Hispano-Romance."Diachronic Studies in Romance Linguistics. Ed. Mario Saltarelliand Dieter Wanner.Paris/Hague:Mouton, 1975. 153-75. Rini, Joel. Motivesfor Linguistic Change in the Formation of the Spanish ObjectPronouns. Newark, DE.: Juan de la Cuesta, 1992. Rosso-O'Laughlin, Marta, and Maria Gonzilez-Aguilar. Atando cabos: Curso intermedio de espaiiol. Upper Saddle River, NJ: PrenticeHall, 2001. Valle-Inclin, Ram6n del. Obras escogidas. Madrid:Aguilar, 1961.