* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download in a magnetized material

Field (physics) wikipedia , lookup

Maxwell's equations wikipedia , lookup

Condensed matter physics wikipedia , lookup

Electromagnetism wikipedia , lookup

Magnetic field wikipedia , lookup

Neutron magnetic moment wikipedia , lookup

Magnetic monopole wikipedia , lookup

Lorentz force wikipedia , lookup

Aharonov–Bohm effect wikipedia , lookup

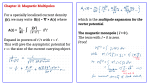

Lecture 8: Magnetostatics: Mutual And Self-inductance; Magnetic Fields In Material Media; Magnetostatic Boundary Conditions; Magnetic Forces And Torques Lecture 8 1 To continue our study of magnetostatics with mutual and self-inductance; magnetic fields in material media; magnetostatic boundary conditions; magnetic forces and torques. Lecture 8 2 Consider two magnetically coupled circuits I2 S1 S2 C2 C1 I1 Lecture 8 3 The magnetic flux produced I1 linking the surface S2 is given by 12 B1 d s 2 S2 If the circuit C2 comprises N2 turns and the circuit C1 comprises N1 turns, then the total flux linkage is given by 12 N1 N 2 12 N1 N 2 B1 d s 2 S2 4 Lecture 8 The mutual inductance between two circuits is the magnetic flux linkage to one circuit per unit current in the other circuit: 12 N 1 N 2 12 L12 I1 I1 Lecture 8 5 12 N1 N 2 12 N1 N 2 L12 I1 I1 I1 N1 N 2 I1 A dl 1 B d s 1 2 S2 2 C2 Lecture 8 6 N1 N 2 L12 I1 A dl 1 2 C2 0 N1 N 2 d l1 d l 2 4 C C R12 1 2 0 I1 d l 1 A1 4 C R12 1 7 Lecture 8 The Neumann formula for mutual inductance tells us that L12 = L21 the mutual inductance depends only on the geometry of the conductors and not on the current Lecture 8 8 Self inductance is a special case of mutual inductance. The self inductance of a circuit is the ratio of the self magnetic flux linkage to the current producing it: 11 N1 11 L11 I1 I1 2 Lecture 8 9 For an isolated circuit, we call the self inductance, inductance, and evaluate it using N L I I 2 Lecture 8 10 iron core I N S air gap with constant B field I Lecture 8 11 N I • Magnetic dipole can be viewed as a pair of magnetic charges by analogy with electric dipole. S Lecture 8 12 N B S Lecture 8 13 Electron orbiting nucleus Electron spin Nuclear spin negligible A complete understanding of these atomic mechanisms requires application of quantum mechanics. Lecture 8 14 In the absence of an applied magnetic field, the infinitesimal magnetic dipoles in most materials are randomly oriented, giving a net macroscopic magnetization of zero. When an external magnetic field is applied, the magnetic dipoles have a tendency to align themselves with the applied magnetic field. Lecture 8 15 A material is said to be magnetized when induced magnetic dipoles are present. The presence of the induced magnetic dipoles modifies the magnetic field both inside and outside of the magnetized material. Lecture 8 16 Most materials lose their magnetization when the external magnetic field is removed. A material that remains magnetized in the absence of an applied magnetic field is called a permanent magnet. Lecture 8 17 The magnetization or net magnetic dipole moment per unit volume is given by M Nm [A/m] Number of dipoles per unit volume [m-3] average magnetic dipole moment [Am2] Lecture 8 18 The effect of an applied electric field on a magnetic material is to create a net magnetic dipole moment per unit volume M. The dipole moment distribution sets up induced secondary fields: B B app B ind Total field Field in free space due to sources 19 Field due to induced magnetic dipoles Lecture 8 A magnetized material may be represented as an equivalent volume (Jm) and surface (Jsm) magnetization currents. These charge distributions are related to the magnetization vector by J m M J sm M aˆ n Lecture 8 20 Magnetization currents are equivalent currents that account for the effect of the magnetized material, and are analogous to equivalent volume and surface polarization charge densities in a polarized dielectric. If the magnetization vector is constant throughout a magnetized material, then the volume magnetization current density is zero, but the surface magnetization current is nonzero. Lecture 8 21 Ampere’s law in differential form in free space: B 0 J Ampere’s law in differential form in a magnetized material: B 0 J J m Lecture 8 22 B 0 J J m 0 J 0 M B 0 M 0 J B M J 0 • define the magnetic field intensity as Lecture 8 23 The general form of Ampere’s law in differential form becomes The general form of Ampere’s law in integral form becomes H J H d l J d s I encl C S Lecture 8 24 For some materials, the net magnetic dipole moment per unit volume is proportional to the H field M m H magnetic susceptibility (dimensionless) • the units of both M and H are A/m. Lecture 8 25 Assuming that we have M m H B 0 H M 0 1 m H H The parameter is the permeability of the material. Lecture 8 26 The concepts of magnetization and magnetic dipole moment distribution are introduced to relate microscopic phenomena to the macroscopic fields. The introduction of permeability eliminates the need for us to explicitly consider microscopic effects. Knowing the permeability of a magnetic material tells us all we need to know from the point of view of macroscopic electromagnetics. Lecture 8 27 The relative permeability of a magnetic material is the ratio of the permeability of the magnetic material to the permeability of free space r 0 Lecture 8 28 In the absence of applied magnetic field, each atom has net zero magnetic dipole moment. In the presence of an applied magnetic field, the angular velocities of the electronic orbits are changed. These induced magnetic dipole moments align themselves opposite to the applied field. Thus, m < 0 and r < 1. Lecture 8 29 Usually, diamagnetism is a very miniscule effect in natural materials - that is r 1. Diamagnetism can be a big effect in superconductors and in artificial materials. Diamagnetic materials are repelled from either pole of a magnet. Lecture 8 30 In the absence of applied magnetic field, each atom has net non-zero (but weak) magnetic dipole moment. These magnetic dipoles moments are randomly oriented so that the net macroscopic magnetization is zero. In the presence of an applied magnetic field, the magnetic dipoles align themselves with the applied field so that m > 0 and r > 1. Lecture 8 31 Usually, paramagnetism is a very miniscule effect in natural materials - that is r 1. Paramagnetic materials are (weakly) attracted to either pole of a magnet. Lecture 8 32 Ferromagnetic materials include iron, nickel and cobalt and compounds containing these elements. In the absence of applied magnetic field, each atom has very strong magnetic dipole moments due to uncompensated electron spins. Regions of many atoms with aligned dipole moments called domains form. In the absence of applied magnetic field, the domains are randomly oriented so that the net macroscopic magnetization is zero. Lecture 8 33 In the presence of an applied magnetic field, the domains align themselves with the applied field. The effect is a very strong one with m >> 0 and r >> 1. Ferromagnetic materials are strongly attracted to either pole of a magnet. Lecture 8 34 In ferromagnetic materials: the permeability is much larger than the permeability of free space the permeability is very non-linear the permeability depends on the previous history of the material Lecture 8 35 In ferromagnetic materials, the relationship B = H can be illustrated by means of a magnetization curve (also called hysteresis loop). B remanence (retentivity) H coercivity Lecture 8 36 Remanence (retentivity) is the value of B when H is zero. Coercivity is the value of H when B is zero. The hysteresis phenomenon can be used to distinguish between two states. Lecture 8 37 Antiferromagnetic materials include chromium and manganese. In antiferromagnetic materials, the magnetic moments of individual atoms are strong, but adjacent atoms align in opposite directions. The macroscopic magnetization of the material is negligible even in the presence of an applied field. Lecture 8 38 Ferrimagnetic materials include oxides of iron, nickel, or cobalt. The magnetic moments of adjacent atoms are aligned opposite to each other, but there is incomplete cancellation of the moments because they are not equal. Thus, there is a net magnetic moment within a domain. Lecture 8 39 In the absence of applied magnetic field, the domains are randomly oriented so that the net macroscopic magnetization is zero. In the presence of an applied magnetic field, the domains align themselves with the applied field. The magnetic effects are weaker than in ferromagnetic materials, but are still substantial. Lecture 8 40 Ferrites are the most useful ferrimagnetic materials. Ferrites are ceramic material containing compounds of iron. Ferrites are non-conducting magnetic media so eddy current and ohmic losses are less than for ferromagnetic materials. Ferrites are often used as transformer cores at radio frequencies (RF). Lecture 8 41 H dl J d s C Ampere’s law S Gauss’s law for magnetic field B d s 0 S B H Constitutive relation Lecture 8 42 Ampere’s law H J B 0 Gauss’s law for magnetic field B H Constitutive relation Lecture 8 43 The integral forms of the fundamental laws are more general because they apply over regions of space. The differential forms are only valid at a point. From the integral forms of the fundamental laws both the differential equations governing the field within a medium and the boundary conditions at the interface between two media can be derived. Lecture 8 44 Within a homogeneous medium, there are no abrupt changes in H or B. However, at the interface between two different media (having two different values of , it is obvious that one or both of these must change abruptly. 1 2 ân Lecture 8 45 The normal component of a solenoidal vector field is continuous across a material interface: B1n B 2 n The tangential component of a conservative vector field is continuous across a material interface: H 1t H 2 t , J s 0 46 Lecture 8 The tangential component of H is continuous across a material interface, unless a surface current exists at the interface. When a surface current exists at the interface, the BC becomes aˆ n H 1 H 2 J s Lecture 8 47 In a perfect conductor, both the electric and magnetic fields must vanish in its interior. Thus, Bn 0 aˆ n H J s • a surface current must exist • the magnetic field just outside the perfect conductor must be tangential to it. Lecture 8 48 The experimental basis of magnetostatics is the fact that current carrying wires exert forces on one another as described by Ampere’s law of force. A number of devices are based on the forces and torques produced by static magnetic fields including DC electric motors and electrical instruments such as voltmeters and ammeters. Lecture 8 49 The force on a charged particle moving with velocity v in a magnetostatic field characteristic by magnetic flux density B is given by F m qv B Lecture 8 50 The force on a charged particle moving with velocity v in a region where there exists both a magnetostatic field B and an electrostatic field E is given by F q E v B Lecture 8 51 The Lorentz force equation can be used to obtain the equations of motion for charged particles in various devices including cathode ray tubes (CRTs), microwave klystrons and magnetrons, and cyclotrons. The Lorentz force equation also explains the Hall effect in conductors and semiconductors. Lecture 8 52 When a current carrying wire is placed in a region permeated by a magnetic field, it experiences a net magnetic force given by F m Id l B C Lecture 8 53 Consider a small rectangular current carrying loop in a region permeated by a magnetic field. y Fm1 B I W x Fm2 L Lecture 8 54 Assuming a uniform magnetic field, the force on the upper wire is The force on the lower wire is F m1 aˆ z ILB F m 2 aˆ z ILB Lecture 8 55 The forces acting on the loop have a tendency to cause the loop to rotate about the x-axis. The quantitative measure of the tendency of a force to cause or change rotational motion is torque. Lecture 8 56 The torque acting on a body with respect to a reference axis is given by T rF distance vector from the reference axis Lecture 8 57 The torque acting on the loop is W W T aˆ y F m1 aˆ y F m 2 2 2 aˆ x ILWB aˆ z ILW B magnetic dipole moment of loop Lecture 8 58 The torque acting on the loop tries to align the magnetic dipole moment of the loop with the B field holds in general regardless of loop shape T m B Lecture 8 59 The magnetic energy stored in a region permeated by a magnetic field is given by 1 1 2 Wm B H dv H dv 2V 2V Lecture 8 60 The magnetic energy stored in an inductor is given by 1 2 Wm LI 2 Lecture 8 61