* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

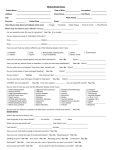

Download Addressing A Uniform National Model For The Dental Assisting

Group development wikipedia , lookup

Dental avulsion wikipedia , lookup

Maternal health wikipedia , lookup

Dental implant wikipedia , lookup

Forensic dentistry wikipedia , lookup

Dental amalgam controversy wikipedia , lookup

Remineralisation of teeth wikipedia , lookup

Focal infection theory wikipedia , lookup

Dental emergency wikipedia , lookup